Peace Without Victory: Adam Tooze on "The Deluge: The Great War, America, and the Remaking of the Global Order 1916-1931"

In case you haven't noticed, this year marks the 100-year anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. Visit a bookstore, and you're likely to be greeted at the entrance by scores of books devoted to explaining how the assassination of Austrian Archduke Ferdinand sparked a European conflagration. Search beyond the piles at the front of the store, and, if you're lucky, you may even find books that explore the war outside of its European context.

But in a year full of books devoted to the centenary of the war, few works have been so eagerly anticipated as that of historian Adam Tooze, whose The Deluge: The Great War, America, and the Remaking of the Global Order 1916-1931 has recently appeared on bookshelves on both sides of the Atlantic. Tooze has long been well-known to specialists on European economic and intellectual history since his earlier work on statistics and state-making in Germany. To more general readers, however, he may be better known for his 2008 The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy, which secured his reputation as one of the leading historians of German and European history writing today.

Economic history may have a reputation as dusty, dry, and, well, boring in some quarters today. But in Wages, Tooze showed how an economic history perspective was crucial to understanding Nazi grand strategy and even the origins of the Holocaust itself. More than that, Wages relocated the pivotal place of the United States in the worldview of Adolf Hitler and other leading Nazi figures. As the United States emerged as a qualitatively new force in global affairs, anyone seeking to shape the global order had to draw lessons from the new colossus. Figures like Hitler recognized that "American economic might would be the decisive factor in the shaping of the world order." More than that, the American challenge was a new political and economic formation on a new scale, "a consolidated federal republic of continental scale, a super-sized nation state" that, thanks to its might and geography, "had a unique claim and capacity to exert global influence."

The American entrance into European and global affairs really took on full shape concomitant to the First World War–an insight that drives much of The Deluge, and which explains its temporal framing. 1916 was the year when American economic output exceeded that of the British Empire, 1931 the year of Herbert Hoover's moratorium on war debts. As commentators today question whether we might be entering a "post-American century," understanding how the American giant burst onto the global scene in the first place is all the more urgent. The Toynbee Prize Foundation had the opportunity to sit down with Tooze recently to discuss his path to history, the book, and his future projects for this installment of Global History Forum.

•

Born in London in 1967, Tooze went through a series of childhood peregrinations that would come to influence the kind of history he wanted to write. While being raised in England in the 1970s, Tooze recalls being saturated in nationalistic images of the Second World War–Churchill, the Blitz, and wartime solidarity. People who had not actually lived through the horrors of the war were encouraged to recall the event as a final moment of glory before the end of empire. Trained as "a good little militarist," then, Tooze encountered culture shock when he, at age six, and his family moved to West Germany in 1973.

Young Britons might have grown up thinking that Germany was still a land of spiked helmets and repressed militarism; and indeed, post-war West Germany had tended towards a forgetting and non-discussion of the Nazi past and the Second World War during the immediate post-war years. But West German political culture changed in the 1960s, and as a result, the Germany that Tooze experienced was one "utterly committed to an anti-militarist vision of culture." Germans, far more than the British, engaged in cutting discussions about culpability and morality during the years of National Socialism and war. A large library helped, too. Given the "virtually unlimited" budget for book-buying that his father extended to son, the young Tooze was soon able to let his reading in English and German range widely. Looking back, Tooze attributes his later historical interests–an interest in hard power and economics, but approached from a position of skeptical anti-militarism–to the two countries in which he spent his childhood.

Studying history professionally, however, was not yet on the table as Tooze returned to the UK for later phases of his secondary education. As he began to consider what to study at university, however, mathematics, not history was the obvious choice. Throughout his youth, Tooze was swept up (along with many) in what is now recognized as the golden age of wargaming. These games might seem to be driven by chance to outsiders, but successful players recognized that victory hung upon the abstract rules behind the games to as to better deploy troops for victory. Tooze, hooked on the games and excelling in his math classes, followed his talents and passions. Soon, he was immersed in readings in game theory and economics. Further, Tooze had attended a specialized school where he was able to explore his talents to a high level; by the time that he was applying to university, he had already developed a graduate-level interest in economic theory. Given that British universities forced students to pick one subject and specialize, Tooze would have to choose: economics or history? "I was better at economic theory," he explains, and so he opted to take his first degree in Economics at King's College, Cambridge.

Tooze was off, then, to Cambridge, to economics. But even as the discipline of economics was rapidly become more academic, mathematized, and abstract during the 1980s, Tooze did not lose sight of the world of politics and history. He notes that he always had "limited sympathy for the Left," but during his Cambridge years he was, briefly, a member of a Trotskyite Party and entertained the anti-Americanism popular among certain left-leaning circles. These political considerations, however, posed professional problems once Tooze began thinking about graduate school. Almost all of the top economics programs were in the United States, and Tooze had a hard time picturing himself living there for any long period of time. What to do?

Clio came whispering. Back before university, Tooze had decided for economics. He had always considered himself more talented in the subject than in history. But now the temptation to diversify weighed on him. And even as many history departments were in the full throes of a turn towards more cultural and social history in the late 1980s and 1990s, Tooze refused to see sharp boundaries between history and the economic training that he had received at Cambridge. "So," explains Tooze, "in 1989 three things happened. The first was that Jürgen Kocka"–one of the major historians of Germany–"decided to move himself and his entire Lehrstuhl (research group), some twenty-five people, from Bielefeld to Berlin. The second was that I decided to move to Berlin to study there. And the third–unrelated, probably, to the first two, was that the Berlin Wall came down." For two years, Tooze imbibed in exhilarating discussions about history with Kocka and collaborators and returned to his German roots. Living at the most historical place in Europe, Tooze was re-orienting himself to be a historian.

Still, he needed professional training. In 1991, Tooze moved back to London to begin graduate work at the London School of Economics. There, he completed his PhD on the history of German statistics. Still conscious about the apparent mid-1990s surge away from economic history in history departments, Tooze considered himself lucky to find employment at Cambridge University, where he taught at Jesus College from 1996. With his first book, Statistics and the German State, out in 2001 and soon the recipient of several prizes, Tooze had established himself as a successful historian straddling economic and German history. At the same time, however, Tooze remained a European historian writing on Germany, but not yet quite placing its history firmly in the broader context defined by American power. The Griff nach Amerika, so to speak, was still to come.

We ask him about the professional advice he might give to students interested, as he then was, in straddling the gap between economics and history. "Anyone wanting to straddle this divide," Tooze answers, "needs to go seriously at it for years." Tooze explains that only thanks to a professional level of interest in economics that dated back to secondary education could he become conversant in high-level debates about economic theory. Even then, he adds, there are certain areas where he senses his own lack of doctoral-level training. And some graduate programs may not offer the pedagogical resources that students need. Economics is a difficult curriculum for graduate students to build, he notes, and it often requires the eclectic mix of faculty that, he adds, institutions like Yale have. He advises historians interested in blending fields to approach economics or econometrics with the seriousness of a foreign language.

"We don't think anything of someone spending an hour every day with a language like Spanish or French, more for German or Russian," he explains, "and Economics is a foreign language of its own." The upside, at least for teachers like Tooze, is that students today are much more sophisticated and better-informed about economics than they were in the 1980s, a development he attributes to the "hipness of the blogosphere" and the fact that his (primarily) American students at Yale can blend economics courses as part of their work towards a Bachelor's degree. Further, Tooze adds, he would never turn down someone with a B.A. in economics who was interested in doing doctoral work in history. It's a refreshingly ecumenical view of the relationship of history and economics as sororal social sciences–even if one not always shared in economics departments themselves.

•

We turn to discuss The Deluge head on. We ask Tooze how he came to the idea of the project in the first place after the success of The Wages of Destruction. Initially, Tooze explains, he thought that he wanted to work on the history of liberal internationalism in the 1910s and 1920s. Several years of wandering through the forest of libraries and archives followed. Tooze wrote parts of a manuscript, keeping some parts and throwing other parts away. Sections of drafts seemed interesting, but Tooze initially struggled to place everything together under one roof. "I have a begrudging respect for historians like Niall Ferguson, who have the amazing ability to pick a theme and know what they're writing about from Day One," jokes Tooze. "I'm not like that."

The more he using writing as a thinking process however, the more that the real plan of the book, as he sees it, emerged: "The Deluge is really just a prequel to The Wages of Destruction." He explains: during the writing of The Wages of Destruction, he had become convinced of the general thesis that the emergence of the United States of America as a major actor played a decisive role in the thinking of the Nazis as they sought to challenge the European and global order. As Hitler realized in the 1920s–and laid out in clear terms in his little-known "Second Book"–even major European powers like Germany were structurally incapable of competing with the United States over the long term unless they a) dramatically increased their agricultural output and b) made a bid for European supremacy sooner rather than later. America was simply too big and growing too fast to be challenged on any other time scale.

The Deluge, Tooze explains, represents an attempt to test this thesis of the centrality of America to European history for the period preceding Wages, showing how the United States played an utterly critical role during the First World War. Readers of The Deluge are unlikely to leave unconvinced of that core thesis, but think of some of the other books published during this year's centenary, and the extent to which the United States hardly figures at all in the narrative can be striking.

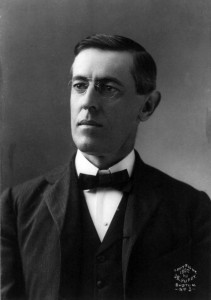

Still, brushing off The Deluge as a mere sequel would sell its ambition short. Indeed, even an in-depth review and interview like this one can only imperfectly touch on a few aspects of what is a long, challenging, and rich book. We start our conversation with the role of Woodrow Wilson in the book. The key place to start, stresses Tooze, is the phrase that Wilson chose to describe America's aims in the European conflict: "peace without victory." (That was also the original title of The Deluge, until publishing vagaries intervened at the last moment.) Research suggested that the phrase had an unusual provenance, namely Copperhead Democrats–members of the Democratic Party from the North during the American Civil War who argued that grinding the Confederacy into submission was impractical, and that true, lasting peace demanded conciliation, not Reconstruction. But what was the link to Wilson and The Great War?

Wilson, it bears recalling, was the first Southerner elected President, and Tooze's portrayal of the Virginia native underscores how much the experience of the American Civil War informed Wilson's thinking. Only the terms set by a compromise with the South (after the failure of Reconstruction), Wilson believed, not the social engineering of the South, guaranteed the domestic peace that provided the bedrock for America's rise to global power from the 1870s to the 1910s. In this sense, Tooze contends, Wilson is far more a figure of the 19th century than of the 20th.

In this sense, Tooze sees himself as dipping his feet into the cataracts and rapids of the massive field of "Woodrow Wilson studies." Since his death shortly after leaving office, Wilson has been interpreted in various guises. But these interpretations may tell us more about the zeitgeist than about the man himself. During the Cold War, it was fashionable to interpret Wilson and his vision for self-determination as an opponent to Lenin and proletarian internationalism. Prior to the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, "Wilsonianism" inspired American neo-conservatives who saw in the Fourteen Points an authentically American tradition for spreading "freedom" and "democracy" to Mesopotamia. Yet the Wilson that comes from Tooze's account is different from both of these. It's also, he notes, more similar to the picture of Wilson that would be recognizable to the President's contemporary critics. It's only, Tooze notes, because later generations of historians necessarily wrote within a "twentieth century" framed by the artificial bracket of 1914 that it became possible to imagine Wilson as a twentieth century figure.

This sense of restraint explains Wilson's attitude towards American engagement with Europe and the world. Consider America's stance towards Germany. After the conclusion of the Second World War, the United States was prepared not only to airlift supplies into Berlin but commit itself to the comprehensive reconstruction of West Germany (including large deployments of American troops there for decades). Wilson, in contrast, was wary of investing incomparably smaller resources to defend the Franco-German border (hundreds of miles west) after the war. If Wilson was really the world-transforming exceptionalist that some of his critics or interpreters would make him out to be, then why didn't he insist on transforming Germany into a protectorate after World War I?

The answer, Tooze explains, has largely to do with the transformation of the American state in the decades to follow (of which more later). But, he stresses, another core reason is Wilson's recourse to the American experience. Reconstruction was not Washington's aim; not in Savannah and not in Berlin. In this sense, Wilson resembled his European colleagues. For Wilson as for French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, it was the lessons of the nineteenth century projected forward, not a visionary view of the century to come, that inspired policy. Wilson saw in the American experience the impossibility of forcing reconciliation onto defeated societies; Clemenceau, in the tides of Franco-German history, the impossibility of beating Germany into submission. Paris would have to accept the existence of a sovereign German state while trying to tame it in concert with London and Washington; Wilson, however, was hesitant for the United States to take on a more activist role in locking a unified German state into some precursor of the European Union or NATO that would place curbs on its sovereignty.

Emphasizing Wilson's 19th century provenance allows Tooze to escape the banality of labels like "pacifism" or "isolationism." Tooze sees Wilson's "peace without victory" strategy as a natural extension of the logic of the United States' earlier Open Door policy. But, explains Tooze, "it is important to be clear what this was not. [This] was not an appeal for free trade. Amongst the large economies, the United States was the most protectionist. Nor did the US welcome competition for its own sake. Once the door was opened, it confidently expected American exporters and bankers to sweep all their rivals aside. In the long run the Open Door would thus undermine the Europeans' exclusive imperial domains." The point, though, is that anti-imperialism was not the same as anti-racism or anti-colonialism. The disruptive vigor of the American economy was no device to usher in racial equality and national liberation in markets like China, India, or the Middle East. Instead, for Wilson as for other American strategists, American anti-imperialism meant opposition to "the 'selfish' and violent rivalry of France, Britain, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Japan that threatened to divide one world into segmented spheres of interest." The late explosion of the American economy into a globalizing world would mean the end to imperial preference, not the end of empire qua white domination.

Hence, even as pro-Entente Wall Street bankers invested hundreds of millions into wartime loans to London, Petersburg, and Paris, Wilson was insistent that the chief American goal was "not that the 'right' side won in World War I, but that no side did." Only in this way could America exploit its economic hegemony and privileged geopolitical location to create a balance of power in Eurasia. This might sound as if America alone was seeking a role of global hegemony for itself, usurping European and Japanese privileges in a way that would offend respectable opinion beyond just imperialist and business circles.

But as Tooze emphasizes, what made this new vision for global order creative, and especially devastating to the hopes of radicals like Trotsky and Hitler (at least in the early 1920s), was that it rested on buy-in from élites across the Atlantic and the Pacific. After 1916, French leaders like Raymond Poincaré and Georges Clemenceau sought to re-orient French security policy away from the odious alliance with autocratic Russia and towards an Atlanticist orientation. From the late 1910s onward, a Reichstag majority of the Social Democrats, Christian Democrats, and progressive liberals remained committed to Germany's Western orientation–if also after the failure to achieve "a legitimate and therefore sustainable hegemony" at Brest-Litovsk. The same was true in Japan, where an emerging system of multi-party parliamentary democracy acted as a check on the country's military. The Soviet Union stood outside of this global consensus, but, Tooze reminds, the Red Army was broken in 1921 by the Polish Army–not exactly a world-beater itself. With Hitler no more than a stateless beer hall rabble-rouser, for much of the 1920s the figures who dreamed of radically overturning the world order remained marginal.

Appreciating that fact helps us understand the broader historiographical ambition of Tooze's work. In The Deluge, Tooze positions the book as an attempt to do nothing less than reinterpret the place of the United States and empire within modern European history. He contrasts his framework to two schools that he dubs the "Dark Continent" approach and the "crisis of hegemony" school. The former (a reference to Columbia historian Mark Mazower's 1998 eponymous work) sees Europe as an arena where "new," dynamic powers–the Nazi New Order, Americanism, and Soviet Communism–successfully challenged stagnant bourgeois republics and empires. Taking the failure of Wilsonianism as its starting point, the "Dark Continent" school asks how "backwards" or "corrupt" Europeans failed to extricate the "old world" from its usual machinations, leading to Europe's turn towards authoritarianism.

The "crisis of hegemony" approach takes a different tack. It looks at the apparent failure of Wilsonianism from another perspective, asking "why the victors [of the Great War] did not prevail. Why does 'the West' not play its winning hands better? Where is the capacity for management and leadership?" Given that the British and French Empires actually expanded after the war, and given the predominance of American financial hegemony, how could ragamuffins like Hitler come to challenge the entire global system?

The Deluge forges a synthesis out of these schools. Apropos of the "Dark Continent" approach, Tooze grants that it's obvious that once the Nazis managed to take over the German state, they were able to reap untold damage onto Europe–until, of course, the victory of the Soviet Union transformed Stalin and his successors into the masters of much of the Continent. Yet reading history backwards through the lenses of 1933 (the Nazi seizure of power) and 1945 (the Soviet victory) can lead us too easily into thinking that these ideological upstarts were predestined to challenge the European order. In fact, for much of the 1920s, figures like Lenin and Hitler remained despondent about their ability to effect a structural change in the European system–the forces of capitalism and empire were just too strong. With the exception of Russia, where radicals took control of the state earlier and managed to survive years of civil war, it was only with the economic collapse of 1929 that it became possible for these formerly hopeless revolutionaries to gain real traction and challenge the international order. Indeed, from the point of view of Moscow it was only with 1929 and the Depression that the logic of History seemed to be going as planned, as capitalist Europe descended into crisis and gave the socialist experiment added legitimacy.

As for the second approach, Tooze stresses the novelty of the post-war situation. Often, he writes, "the disasters of the twentieth century are ascribed to the dead weight of the past." We assume that the contradictions of something called imperialism led to global economic collapse, or that Germany's ambition to acquire a colonial empire for itself in Eastern Europe was just a rerun of European empires in Africa or Asia.

But what do we really mean by "empire"? Too often, Tooze insists, we proceed from a concept of "imperialism" as a static force unchanging from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. But an approach that stresses the continuity of empire fails to "encompass the unprecedented pace, scope and violence of change actually experienced in world affairs from the late nineteenth century onwards." As Tooze notes, "modern global imperialism was a radical and novel force, not an old-world hangover." The word "imperialism" itself only acquired currency around the year 1900; that itself suggests that contemporaries only grasped the problem of constructing a hegemonic world order quite late into what we think of as the period of European imperialism. More than that, Tooze adds, his reading of the sources suggests that by 1920, historical actors had the sense that they were passing into something like a "post-imperialist" moment, but felt that they lacked a "historical model of world hegemony with which to address it."

If the reader accepts this analysis, then she needs to re-assess figures like Clemenceau or Lloyd George less as content old imperialists and more as actors struggling to articulate a new global order in the face of unprecedented challenges. Lloyd George in particular aspired after the peace to feats of world financial and strategic coordination that exceeded anything achieved during the Victorian period, but these attempts cracked apart. Proponents of the "failure of liberal hegemony" school might point to the persistence of British rule in India, or the expansion of the British Empire in the Middle East after the War as examples of continued hegemony. But as Tooze convincingly suggests, "this was truly the exception that proves the rule." Britain's wartime dependence on US supplies whose price was denominated in dollars forced London to squeeze South Africa and India for their supplies of gold and silver, fueling movements for Home Rule in both countries. Advocates of a persistent "imperialism" need to explain why the British Empire of 1919–near its peak in terms of geographic scope and complexity–was giving not taking independence to places like Ireland and Afghanistan. These, Tooze insinuates, are signs of a search for global order ab imperio, not of continued good luck and domination. While facing down all of these challenges, moreover, London faced huge debt payments to Washington.

The problems confronting Paris, however, illustrate how massive "the deluge" of challenges really was. Franco-German relations, Tooze notes, underscore how "all of the difficulties of the postwar settlement emerged from the fact of German sovereignty." Confused, we ask Tooze if he is referring to cases like the Saarland or Danzig. "No," he responds, "I mean the core German state itself." A close reading of the book clarifies his stance. Since Germany's defeat of Russia in 1917, the core constraint on German power in Europe from the East had been removed. But "for France as for Germany this had dramatic implications. It was the common fear of the unified Reich that had brought Tsarist Russia and republican France together in an incongruous alliance."

Without Russia–or the Soviet Union–as part of a common front, however, France required extraordinary guarantees from the United States or the British Empire. When Clemenceau failed to respond constructively to a 1919 British proposal for a trilateral Franco-American-British security pact, it was because he required the guarantee of British and American participation in the initial (1919) occupation of the Rhineland. Given that marauding German armies had devastated France's economy during their occupation of northern France–apparently "to cripple their economy permanently"–any responsible French statesman required long-term guarantees of locking Germany into structures of trans-Atlantic military and financial hegemony. British disagreements with the French on this matter might have only been technical, but the real sticking point was that such demands ran counter to Wilson's vision of "peace without victory." If Reconstruction had not worked in the South, how could it work in the Rhineland?

Aggrieved French and Belgian élites pointed out that Wilson had refused to visit the devastated areas of their countries so as not to upset his "emotional equilibrium" prior to Versailles. But in any event, not having visited the ruined areas, Wilson quickly backed away from his short-lived guarantees that France constituted "the frontier of freedom" or that "whenever France is threatened the whole world will be ready to vindicate its liberty." France was left to contend with a sovereign German state not only without a strong Russian ally–only newborn Poland and Czechoslovakia–to the east, but also without ironclad Atlanticist guarantees. German sovereignty meant that Paris would always feel threatened; it also meant that, with its own currency, Berlin could inflate away its debt while France remained burdened with huge dollar-denominated loans. Without a significantly larger American appetite either to occupy Germany or coöperate more intensely with France, the threat of re-energized German statehood cast a shadow over the Rhine.

Lloyd George managed to square this circle for several years and attempted, at Genoa in 1922, to negotiate a bid for massive foreign investment in the Soviet Union through a British-French-German consortium, the profits from which could pay off German debt to London and Paris, and later debt to the Americans. Moscow, however, derailed the conference by signing a separate deal of mutual recognition and cooperation with Berlin in nearby Rapallo, presenting London and Paris with the threat of a German-Soviet alliance combining German expertise with the vast raw materials of the former Russian Empire. The deal revealed how fragile British and French "imperialism" really were. Without a renewed European financial architecture, London would remain bogged down in debt and facing enemies from Mesopotamia to Mitteleuropa. The challenges facing "imperialism," recognized Lloyd George, were clearly far more daunting than those of the Victorian Era. They were challenges that could only be met with the financial, political, and military resources of the United States.

Hence, when Lloyd George's Genoan hopes for a European-Soviet condominium of investment and debt payoffs disintegrated, France felt forced to act. A Soviet-German rapprochement threatened to throw a depleted France against a Eurasian juggernaut of expertise and natural resources. But there was a way out. As Tooze explains, "an act of state violence was cashed out in remarkably stark terms. Paris calculated that the cost of sending the French Army into the Ruhr, the heartland of German industry, would be as little as 125 million francs. The return from the exploitation of the Ruhr's coal mines could be as much as 850 million gold francs per annum." The Americans shrunk from serious action: no debt jubilee for the French, and only the vague resolution to send commissioners to determine Berlin's ability to pay off its debts. Unimpressed, in early 1923 Paris sent the French Army of the Rhine into the Ruhr, crippling the German economy. The exchange rate of the mark to the dollar, formerly 7,000:1, instantly hit 49,000:1 and skyrocketed to 6 million to one by the summer.

But Parisian markets slid, too. In light of the financial cruch, French negotiators agreed to withdraw the troops in exchange for an $100 million credit for J.P. Morgan, part of the larger architecture of the Americans' so-called Dawes Plan. Having evaporated its debt (and potentially ruined its creditors) through hyper-inflation, Berlin would still be on the bill for financing reparations payments from a putative budget surplus, aided by guarantees of $800 million in US investment. Germany, which according to Versailles, had started the war, received the money while being governed by a formerly openly pro-annexationist Chancellor; France's $100 million credit was explicitly conditional on good behavior in the realm of foreign policy towards the Reich.

It was an odd arrangement: even as J.P. Morgan and other Wall Street titans could look forward to a favorable 5% return from German servicing of bonds, Morgan was bewildered by the role that he was being asked to take on. Not only Germany's future, but French foreign policy was being dictated by the United States–in partnership, ironically, with "the first socialist government elected to preside over the most important capitalist centre of the old world," in Britain's Labour. The Wilsonian vision of achieving "peace without victory" in Europe was being achieved through American financial hegemony, but in a halting manner and one that failed to appreciate the magnitude of the financial and security architecture the moment demanded.

Still, for a time, Europe had seemingly been anchored into a system of American financial hegemony–if also one increasingly borne by Wall Street and convinced that America's primary role was to extract debt payments from the Continent, not to transform it. And in this sense, Tooze stresses, there was more continuity among 1920s Democrats and Republicans than distinctions between an "activist" Wilson and an "isolationist" Harding or Coolidge might capture. Both agreed on the need to avoid complicating foreign entanglements, if for different reasons. Whether the goal had been that of early twentieth century Democrats (remaking the federal government) or Republicans (generating unprecedented Gilded Age wealth), America's future required standing distant from Europe and not getting involved in the disputes of the old continent. Given that the traumas of the Civil War and Reconstruction were relatively fresh and that America was in the midst of an unprecedented wave of immigration of "foreign" Orthodox Slavs, Jews, and Catholic Italians and Irish, stability not adventurism was paramount. Re-designing the entire fiscal, monetary, and foreign policy of European states was not the business of an American government that itself had less than a decade's worth of experience administering a federal income tax at home.

When the Great Depression of 1929 hit, however, Washington was forced to acknowledge that the impulse that united Wilson and Hoover–"to hold at bay the disruptive ideologies and social forces of the twentieth century, so as not to disturb the American equilibrium"–had been undone. The post-Depression United States was forced to come to terms with the contradiction that haunts American debates about the country's role in the world today. If early twentieth century American internationalism meant "merely" the surge of American capital and expertise into every part of the world, the breakdown of European order and the increasingly militarist challenge that regimes in Berlin, Tokyo, and Italy later posed. Like it or not, America had to transform its massive "empire of production" into an unprecedented platform for projecting power worldwide if it wanted to maintain its role of leadership.

The paradox, as Tooze concludes, was that the still-massive lead that Hoover and FDR's America enjoyed lent "insurgents"–the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, and Imperial Japan–a sense of urgency that would propel radical transformations in those societies. "Too often and too easily," he explains, "we write 'interwar history' as though there was a seamless continuity between the phase on which we have concentrated here, 1916-1931, and what came after in the 1930s."

But this fails to capture the extreme sense of urgency that gripped authoritarian leaders. The revisionist powers that came to challenge Western hegemony realized that they were operated from a position of weakness that could be overcome only with truly radical measures. At the London Naval Conference of 1930, for example, neither the Soviet Union or Germany had a navy to barter with at all; Japan's and Italy's fleets, meanwhile, were clearly second tier. Only through radical re-armament could one break the Western hegemony whose cracks had become apparent at Genoa, and which the Great Depression exposed most fully.

Hence, by 1938, Tokyo was spending thirteen times its 1913 level of military spending; the Nazis devoted seven times as much to arms as the pre-World War I German Reich, and Stalin almost five times as much as the Tsars ever had. Even as America adopted a stance of "privileged detachment," the "present absence" of the United States in world affairs remained so great than only a truly radical break with past traditions could challenge the "super-state" on an international stage.

•

That story, of course, leads back to this "prequel's sequel"–The Wages of Destruction, the impetus for Tooze's research for The Deluge. Having completed this story of the United States and Europe, during the current academic year Tooze is back in New Haven, where he faces the challenges of how to teach the kind of expansive history embodied in his work to undergraduate and graduate audiences. In addition to serving as a "willing conscript" for John Gaddis' and Charles Hill's Grand Strategy course, Tooze has been teaching a course on the history of the Great Recession as a historical event and a course on "the history of the present" to students in Yale's Global Affairs Master's program.

The courses present different pedagogical challenges. The Great Recession course, Tooze explains, was partly inspired by a Spring 1991 piece by Harvard historian Charles S. Maier, who then took the opportunity of the collapse of Communism to ponder how historians would write about the event in historical context. A generation removed from Maier, Tooze seeks to take advantage of an event of similar magnitude to ponder what contemporary figures mean when they describe the current global recession as a historical event. What vision of economic history do public intellectuals like Paul Krugman, Niall Ferguson, Martin Wolf, or Joseph Stiglitz imply when they write about the Recession as a turning point? Forced to explain why the crisis exploded when it did, intellectuals might point to different turning points–the 1999 repeal of Glass-Steagall, Alan Greenspan's tenure as Fed Chairman, the growth in Asian savings rates since the late 1990s financial crisis–that caused 2007-2008 to become such an acute tipping point. Or they might point to the post-2008 trajectories of various advanced industrial economies to argue for policy prescriptions. Does the U.K.'s comparatively high growth relative to the Eurozone mean that austerity has indeed worked, and that 2008 marks the end to the welfare state as we know it? Or does the sluggish growth in wages there and in the U.S.A. suggest rather different models for understanding relations between labor and capital? These are questions hotly contested by economists and journalist, but they're also historical questions that historians can approach.

The "history of the present" course poses challenges more familiar to readers of the Global History Forum, namely of how to teach global history. Tooze admits that his approach is eclectic. "Basically," he says, "I would encourage students to read The Economist and Foreign Affairs and find themes that seem to be amenable to historical analysis. Which themes speak to us as historical actors?" He names the West African Ebola crisis or the rise of China as obvious examples, and adds that one could quickly draw up a list of the big issues: global finance, disease control, population control, migration, development, global science, and so on. From there, the question becomes identifying historical episodes–the eradication of smallpox or the Spanish Flu; the rise of Wilhelmine Germany–that merit exploration.

The payoff, Tooze explains, is not just engaging history but a renewed sense of "history as the medium in which we live our lives." Without this kind of historicism-as-presentism framing, it can be easy to dismiss the world before 1914 as a "candyfloss world" with little relevance to today, when in fact, Victorian or Wilhelmine actors encountered problems that we would dub "global" quite often. Teaching to an audience of Global Affairs students, Tooze seeks to impart onto them the importance of grappling with historical material while also remaining conscious of their position "as someone writing in 2010, or 2014," as someone trapped in the flow of history themselves.

While testing out global approaches in his current teaching, Tooze eagerly follows the discipline as new works appear. Asked to recommend one book in particular that he views as essential, Tooze names Marilyn Lake's and Henry Reynolds' Drawing the Global Colour Line: White Men's Countries and the International Challenge of Racial Equality, a book that is "strikingly successful" at anchoring a specific debate–the challenge of racial equality as presented by Japanese and African-American activists against the Anglo-American settler colonial world–in broader concerns about global migration. But he also names SUNY-Albany professor Ryan Irwin (featured in an upcoming Global History Forum interview) and Pennsylvania historian Vanessa Ogle (featured in a recent Global History Forum interview here) as two rising stars. Irwin wrote his first book on the global debate over apartheid and is currently researching a project on the intellectual history of American liberal internationalism; Ogle's first book, on the global history of universal time synchronization, is scheduled to appear soon with Harvard University Press.

Of course, Tooze remains poised to contribute to the emerging field in big ways himself. At least two projects remain in the works. One is what he sees as the missing link between The Wages of Destruction and his latest work, namely a history of the transformation of the American state into the world-making apparatus it became by the middle of the twentieth century. As much as World War I-era Republicans might have deplored Wilson for his lack of a more aggressive intervention into Europe–transforming Germany into a direct protectorate, for example–Tooze respects Wilson's realism for not seeking to impose Reconstruction on the Reich.

But, he notes, this reflected not just Wilson's Southern background but also the recognition that the American state still lacked the institutions to transform foreign societies. As Tooze explores in The Deluge, Wilson sought to change this: Wilson's peace policy was partly designed to insulate his domestic reform programs from the international crisis, and it was under Wilson that the Democrats introduced wide-sweeping changes like the Federal Reserve system and the income tax. But only once the American state had been reinvented domestically could Washington unleash a "New Deal for the World" onto post-war European and Third World societies. Tooze ponders writing the story of this American transformation, one partly explored by scholars like Elizabeth Borgwardt and David Ekbladh (a Toynbee Prize Foundation Trustee), but in such a way that brings his own strengths finance and the state to the forefront.

Another research agenda, laid out in a recent lecture at Stanford, seeks to unify local history with global history. Recently traveling around the regions of southwestern Germany, Tooze grew fascinated by Häusern, a tiny hamlet in Baden-Württemberg that's probably not on the mental map of most historians of Europe, much less historians of Germany. Yet during the 1920s and 1930s, experiments in cooperative-driven agriculture in Häusern attracted great interest from German and foreign visitors concerned with the future of European agriculture. (A paper summarizing some of Tooze's research is available here.)

Discussions of grain yields and tool-sharing might seem like the only thing more soporific than pig iron and steel ingots–the usual biased images of economic history–but this all amounts to nothing more than an anachronistic view of twentieth century European history. We tend to imagine history as being made in great metropolitan centers, but it was not until the middle of the twentieth century that city-dwellers outnumbered farmers, even in Europe. And prior to the Green Revolution of the mid-twentieth century, crop yields were much more modest than what those of us living in the early twenty-first century take for granted.

It's in this context that situating seemingly local debates like those in Häusern assumed larger importance. As the German state was transformed into a colonial power that sought to remake Eastern Europe–above all Ukraine–into a dystopian breadbasket that would reverse Soviet agricultural policies, agronomic debates centered around unlikely "local" contexts like Häusern assumed outsized weight. Follow the agronomists in the parochial 1920s context into the Cold War, Tooze shows, and the story becomes global, as German agricultural experts traveled to locales like Turkey and Ethiopia make the Third World resemble less the Soviet Union and more places like Häusern. It's another example of how German and even local history, viewed with the proper expansive spirit, can be seen as part of a global story.

German history, economic history, and global history–with so many different moving parts, Tooze's research agenda is impressive, if not intimidating. It's little wonder, then, why The Deluge is one of the most eagerly anticipated works of history appearing this autumn–with good reason, too, as our reading of the work and conversation with Tooze indicates. We're delighted to feature him as our latest guest.