Chinese Jesus: Discussing German Missionaries' Journey "From Christ to Confucius" with Albert Wu

Is Christianity in danger of disappearing? Since at least the middle of the twentieth century, Christianity in Europe has often been seen as in decline, with the most recent surveys indicating that scarcely more than half of EU citizens believe in any God at all. Many Christian communities in the Middle East, such as the Assyrians, have been displaced through the US invasion of Iraq, the Syrian Civil War, and the emergence of ISIS. The Eastern Orthodox Church, freed in its Russian incarnation from decades of Communist rule, shows strong signs of growth in Europe. However, the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the displacement of Russians means, increasingly, that Orthodoxy's southern frontiers end thousands of miles further north than they did a century-and-a-half ago.

In fact, Christianity in the world is in no danger of vanishing. The percentage of Christians as a part of world population is nearly the same as it was a century ago. What is changing, however, is the face of Christianity, as both the Roman Catholic Church and Protestant denominations see more and more of their congregations be composed of Latin American, African, and Asian populations. Pope Francis is the first Pope from Latin America, while Brazil constitutes the single largest Catholic country. There are almost as many Catholics in Nigeria as there are in Germany. There are perhaps tens million of Chinese affiliated with official state-sponsored Protestant organizations in that country, but the proliferation of unofficial "house churches" means that there could be up to 58 million Protestants and 9 million Catholics living in the People's Republic of China. This, in turn, would make China the fourth-largest Protestant country after only the USA, Nigeria, and Brazil.

Demographic changes like these are bound to bring about conversations about theology and dogma. To take the example of the Anglican Church, bishops from the "global South" have boycotted conferences on the grounds that North American churches are too lenient on the ordination of homosexual bishops and their blessing of same-sex marriage. Conversely, many theological conservatives who approved of Joseph Ratzinger have expressed concern over the stress that Pope Francis has placed on issues such as global warming, consumerism, and US-Cuba relations (his more traditional views on matters such as abortion and same-sex marriage notwithstanding). As nations whose entry into Christendom is inescapably entangled with European imperialism come to occupy greater prominence, the question of how "North-South" relations will affect Christianity cannot but occupy the attention of Christians and non-Christians alike.

Our latest guest to the Global History Forum, Albert Wu, offers perspectives on these question in his recent book, From Christ to Confucius: German Missionaries, Chinese Christians, and the Globalization of Christianity, 1860-1950, published with Yale University Press.

In his book, Wu (an assistant professor at the American University of Paris) explores how German Protestant and Catholic missionaries engaged with China during the late Qing period and during the Republican period. At the heart of the book stands a paradox. At the start of the period in question, German missionaries viewed Chinese Confucianism as backwards and a crucial hindrance to China's conversion and, more broadly, modernization. Yet by the 1930s and 1940s, German Christians viewed Confucianism as a crucial ally of Christianity in China. They insisted that a synthesis of Confucianism with Christianity constituted not heresy but rather only common sense. Wu's book explains this paradox of how Germans "struggled to make a religion with universal claims adopt particular forms" and "how a global religion should assume local guise."

As many Christians on both sides of the North-South (not to mention European Muslims in search of a "European Islam") debate these questions, Wu's book provides useful historical perspective. Outgoing Toynbee Prize Foundation Executive Director Timothy Nunan recently sat down with Wu to discuss From Christ to Confucius as well as Wu's ongoing research agenda.

We begin our conversation with Dr. Wu by asking him to describe his path to the historical profession. He was born, he explains, in Houston, Texas, where his father, an international student from Taiwan, was completing a PhD in physics. His father's subsequent work took the family to Huntsville, Alabama (home to American rocketry and space flight centers), but by the age of six, Wu and the family were headed back to home – Taiwan. He grew up there, but attended a bilingual school, giving him a native command of both Chinese as well as English.

However, an interest in history, much less religious history, was not obvious from the start. Only during a sabbatical of his father's (this time to Cambridge, England) did Wu begin to kindle an interest in history proper, thanks to outstanding teachers there. An uncle in Taiwan was a Presbyterian minister, meanwhile, and many of the students at Wu's bilingual school regularly attended church. It was there that he was drawn to Christianity, but he did not envision that he would later study its history.

The confluence of religion and history intruded into Wu's consciousness as he began his undergraduate education in New York City—namely, at Columbia University. "I enrolled at Columbia the week before 9/11," he explains. The World Trade Center went down during Wu's freshman week of classes, and in many ways subsequent US political debates about the invasion of Afghanistan and, in particular, Iraq, informed his thinking about religion and politics. While on campus, Wu became involved with InterVarsity, an on-campus Christian fellowship. A friend from InterVarsity took him to a church that openly supported the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Personally opposed to the war and disturbed by some of the rhetoric that other church-goers used to justify their support of it, Wu became interested in how religious groups mustered theological arguments in favor of policy, as well as how theology was entangled with geopolitics.

This personal journey soon influenced Wu's undergraduate work. He enrolled as a sophomore into a Columbia History Department course, "The Historian's Craft," with Elizabeth Blackmar. The course was designed for seniors writing History theses, but Wu used the course to write a paper on the history of anti-Vietnam War clergy on American university campuses. He studied noted figures like the Yale chaplain William Sloane Coffin and the Jesuit priest Daniel Berrigan, but he came to focus on Columbia's chaplaincy, led by Reverend John D. Cannon. (Columbia's chaplaincy was terminated in 1969 as a result of anti-war protests, but later reinstated in 1996). Wu was interested in Cannon's political activism, but he focused in particular on how the Chaplaincy in the 1960s essentially "self-secularized" – going from being an Anglican church to non-denominational. How was political activism connected with this form of secularization, he wondered? Similarly, classes with historian Samuel Moyn in which he read books like Marcel Gauchet's The Disenchantment of the World influenced his thinking.

Wu was inspired enough to pursue a PhD in history—although, he notes, at the time, he was still primarily thinking about working on European history without any conscious transnational or global dimension. After a year in Germany spent honing his German, he was off to the University of California, Berkeley, where he worked with Margaret "Peggy" Anderson. Wu's initial thought (a pattern, as we will see) was that he would put religion behind him, since he had focused on the theme at Columbia. But the more he read and took courses, he found himself coming back to the theme. Then, he thought he would focus on religiously conservative evangelicals in nineteenth century Prussia and their approach to the "Social Question" – a respectable, safe, mainstream topic. Theological conservatives had been neglected in the literature on religion in nineteenth century Germany, and this would be his chance to intervene in the scholarship.

But Anderson intervened and encouraged him to take advantage of his native Chinese. Wu was reluctant at first—he wanted to be a Europeanist, after all. But it soon became clear that using the lens of German missionaries in China could be a useful lens to examine the same themes of theological conservatives Wu had intended to examine in a domestic frame. Soon, having completed his coursework and submitted a prospectus, he was on his way to the archives of the Berliner Missionswerk (BMW), one of the major evangelical missions to operate in late nineteenth century and early twentieth century China. Many rounds of phone calls and e-mails later, he was also able to access the archives of the Society of the Divine Word (SVD) located in Rome. These, along with other archives in Taiwan, the USA, and the Vatican, formed the archival basis of Wu's dissertation and, later, book.

Before moving on to discuss some of the arguments and themes in From Christ to Confucius, we ask Wu if he would like to offer any general advice to graduate students beginning their own projects. He stresses that he would encourage graduate students to "be as broad as the curriculum" allows during their first years of coursework and field reading. His professors at Berkeley encouraged him to take courses in as many different fields as possible, and the program was designed to allow students the flexibility and time to take a variety of courses prior to their field exams in their third or fourth years. That meant that Wu was able to pursue not only a deep grounding in topics like the Kulturkampf and the Boxer Rebellion, but also to gain a comparative view through courses in Russian history as well. That breadth certainly shows in the pages of From Christ to Confucius, to which our conversation now turns.

Turning to the main themes of the book, we start by asking Wu two questions: first, why was China important to missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries? And second, what value does it add to examine how German missionaries engaged with that country?

As to the first question, Wu explains that it has an obvious and not so obvious answer. China was then as now the world's most populous single country, which made for lots of souls to convert. Further, the late nineteenth century presented missionaries with an unprecedented opportunity. Early Qing rulers had allowed Jesuits into the country as curiosities "useful in introducing the empire to Western commodities and ideas," but by the early 18th century, disputes between the Qing and the Vatican led to the Empire banning all missionary work. A century or so later, however, the Qing were on their knees against the European empires, and missionaries increasingly had room to proselytize. The geopolitics alone, in short, made China an interesting case study.

More substantively, however, the German missionaries that Wu studied viewed the Chinese as superior to the African peoples, whom they also attempted to convert. In Germans' eyes, Africans were so-called Naturvölker ("natural peoples") without any cultural, intellectual, or theological heritage. Converting them was simple, the missionaries believed, due to this theological void. Conversely, European missionaries asserted that the Chinese were Kulturvölker—peoples of culture—upon whom Confucianism had made a deep imprint. This made spreading the Gospel more challenging, since there were native traditions to resist. But it also meant that if Christianity could be spread among the Chinese, it could be spread elsewhere. Not only Naturvölker but other more civilized peoples such as Indians, Egyptians, Persians, etc. could be converted if missionaries proved convincing enough in the crucible of a 5,000-year old civilization.

What does German perspective add to Wu's account? Most scholarship has focused on English-speaking or French missionaries in China, and as Wu notes, "American and British Protestant missionaries outnumbered Germans, and the number of German Catholic missionaries ranked below their French and Belgian counterparts." From a historiographical perspective, this meant that Germans had tended to be overlooked. But the size of national missionary groups was not decisive, Wu argues. For one, Germans enjoyed international prestige as theologians. As a result, "the international missionary community took German missionary theologians seriously. Within both Protestant and Catholic spheres, German missionary ideas often defined the grounds for the missionary debate."

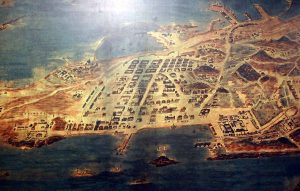

More than that, however, precisely because Germans were relatively pipsqueaks in the missionary game, their writings were suffused with more reflection about the entire enterprise—and what success in it might mean—than their British, American, or French counterparts. Germany was famously a latecomer in its acquisition of an overseas empire, and only in 1898 did it manage to acquire a concession in Qingdao, China (famous in the West today as the home of China's most successful export beer, romanized as "Tsingtao"). More than that, defeat in World War I stripped Germans of their colonies entirely and prompted several theologians to reflect on their commonalities with (not superiority over) people similarly subjugated by British and French imperialism. (Similar to the work of another Global History Forum guest, Susan Pedersen, the German perspective provides a novel lens into interwar debates about the unfair hierarchies of a British- and French-centric "West" over an African, Asian—and German—"Rest.")

Not to be overlooked, too, Germany was a country with deep connections to the worlds of Protestantism and Catholicism. In writing the book, Wu notes, he wanted to perform a "cross-confessional analysis" in contrast to prior works that had focused on one group or the other. More than that, Germany's missionary scene was big enough to have a diversity of views. Faced with waves of rootless migrants in industrial cities and concerned about post-1789 rationalism (not to mention Napoleon's destruction of ecclesiastical institutions), both the Protestant Berlin Missionary Society as well as the Catholic Society for the Divine Word were concerned about winning souls in Germany itself as well as abroad. And as we will see later, while challenges to the faith both in the West prompted some to turn to a more liberal modernist theology, many of the thinkers whom Wu explores were to insist on the primacy of Biblical fundamentals over a "social gospel" message.

This focus on theological conservatives matters, argues Wu, since much of the literature on secularization and religious dialogue emphasizes the importance of liberal trends, such as critically reading the Bible as a historical source and a focus on works. Bucking this trend, Wu argues that, among German missionaries, openness toward the non-Western world and non-Christian faiths emerged not because of their liberal modernism, but rather because they came to view Chinese Confucianism as a bulwark in a world of liberal modernist Christianity (and, worse, socialism and Bolshevism). Looking at the German case thus becomes not just an additional case study but also a critical intervention into debates about religious diversity and conversations between faiths.

Still, these themes might best be illustrated through a more granular engagement with Wu's work. In the mid-19th century, German Protestants and Catholic missionaries sought to expand the theological revival taking place in Europe to China. Yet as missionaries trained and deployed to East Asia, Wu explains, they embodied a very different view of Chinese heritage than had the first Jesuit missionaries to China. Early Jesuits, Wu notes, had seen Confucius as a kind of world-historical figure of importance to humanity — similar, perhaps, to Muhammad or the Buddha. In contrast, 19th century missionaries viewed Confucianism as a sad stumbling block that was preventing China from entering the modern world. Unabashedly Eurocentric, they viewed Confucianism as the root of all of the evils that plagued Qing China: foot-binding; excessive veneration of ancestors and the past; opium consumption; polygamy; and an obsession with rote learning for Imperial examinations.

This period of 19th century missionary engagement is usually presented (in retrospect) as one of optimism. But in examining the sources of Catholic and Protestant missionaries, Wu found almost the opposite. Missionaries struggled to master the Chinese language and its many local dialects. Attrition rates for missionaries were quite high due to depression, disease, and anti-foreigner sentiment. And where missionaries were able to convert Chinese, what Wu dubs a "hermeneutics of suspicion" persisted vis-à-vis the candor of their Christian faith. Paradoxically, Chinese converts were scrutinized more closely than their African equivalents — the idea partly being that because the Chinese were a Kulturvolk, the faith had to work in them more deeply to really take.

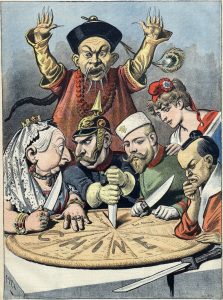

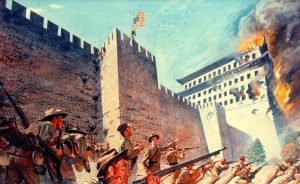

The result of it all by the end of the nineteenth century was not so much optimism as rather a strained situation. Chinese Christians often felt that they were not taken seriously either by foreign missionaries or by Chinese reformers interested in discarding the incompetent Qing state for a Han national state (whether Christian or otherwise in orientation). Yet missionaries, for their part, were concerned that without more scrutiny of Chinese, the risk of perversions of Christianity taking root and being propagated by charismatic preachers was too great. Indeed, it was partly due to the spread of esoteric and syncretic millenarian views that the Taiping Rebellion (the largest conflict of the entire nineteenth century) had exploded and done lasting damage to Christianity's image in China. Since then, moreover, the decline of China vis-à-vis Britain, France, Germany, Russia and Japan engendered more xenophobia. In 1889, the wick on the powder keg burned out, and a mass uprising (the Boxer Rebellion) led to the massacre of missionaries and Chinese Christians.

A multilateral imperialist intervention put the rebellion down. The Great Powers imposed reparations (worth $10 billion in 2017 dollars) on China to atone for their bad behavior. For the moment, the pattern of China's humiliating relationship with the imperial powers (and foreign missionaries) could be restored. Yet missionaries were far from on the upswing. If they were not to fan the flames of a second Boxer Rebellion that might topple the imperial order altogether, how could they spread their faith?

The solution, as Wu explains in From Christ to Confucius, was a policy of "indigenization." Over time, Chinese Christians would have to manage their own Church. Not only did native speakers of dialects have a massive advantage in spreading the Word of God, but training them was far cheaper than the sums involved in European missionary education and travel to and from China.

But how was this to be accomplished? Here, opinions differed. As early as the 1860s, American and British missionaries debated this question and proposed a "Three-self" formula. Chinese churches should be "self-supporting" (financially independent), "self-governing" (led by indigenous clergymen) and "self-propagating" (propagating the Gospel themselves). But these were just one idea among many. Many missionaries remained unconvinced about the depth of Chinese conversions, and their basic suspicion toward Confucianism and Chinese culture also rendered them suspicious toward any kinds of syncretism that indigenous priests could introduce into the faith. In a sense, the missionary enterprise was caught between the dilemmas posed by the rebellions that bookended the previous half-century. Over-indigenize, and missionaries might risk perverting the faith (and creating millenarian cults). Under-indigenize, and Chinese nationalism could wipe out the missionary presence in China altogether.

German missionary groups made halting steps to take Chinese Christians seriously in the first decade of the new century. At a 1911 conference between the Protestant BMS and Chinese Christian assistants (Gehilfen), the Germans agreed to tone down nude depictions of Christ (nudity was seen as an aesthetic taboo in China) and guaranteed their Chinese assistants pensions and raises. Still, the SVD and BMS ordained only single-digit numbers of priests by 1911, and nearly all worked in congregations under missionary supervision. The "hermeneutics of suspicion" was slow in fading.

Perhaps the most important changes were external. In 1911, the Qing Empire collapsed, transforming the ideological battlefield on which missionaries saw themselves fighting. As Wu explains,

Of the three dominant visions for the modernization of China, Christianity seemed the most viable. Traditional Chinese religion—in their definition, "superstition"—had been trampled when international troops defeated the Boxers. Similarly, the old Confucian order had been overturned with the overthrow of the Qing Empire. With it, the Chinese reformist view of synthesizing Confucianism with Western ideas also was in peril. The chaos that surfaced during parliamentary debates only confirmed to missionaries the fragmentation within the Chinese intellectual sphere. Where, then, could Chinese intellectuals, and the Chinese people in general, turn? With Confucianism and traditional Chinese religion no longer legitimate competitors, missionaries believed that only Christianity could fill that ideological vacuum.

Notably, however, some of the civilizational keys in which missionaries addressed China were also changing. Rather than viewing Europe as an inherently superior civilization, many reasoned that Christianity had filled the moral vacuum left behind by the collapse of the Roman Empire. Just as Christianity had civilized barbarians in Europe, so, too, could it do the same to devotees of traditional religion or Confucianism in China.

Yet another outside event—the First World War—upset these plans. Most obviously, the War did much to discredit assumptions about European superiority, as millions were killed in a senseless meat grinder. More specific to Wu's concerns, however, Article 438 of the Treaty of Versailles turned over German missionary property to the victor states, outraging German missionaries Protestant and Catholic alike and seeding within them a distrust of the British as double agents. For Christians in Germany, the war brought not only national humiliation but also the emergence of violently anti-Christian movements in Soviet Russia, and the near-establishment of left-wing regimes in Budapest, Munich, and Berlin.

Not only that, the moral landscape of China was changing, too. Chinese nationalists were outraged that Versailles had awarded Shandong (the German colonial possession) not to China, but to the Japanese. Incensed, a young Mao Zedong cited the turnover as proof that the Great Powers were nothing but "a bunch of robbers bent on securing territories and indemnities" even as they "cynically championed self-determination." Mao's nationalism and anti-imperialism was just part of a larger debate in China over how to reinvigorate Chinese civilization. Many of the Chinese Christians that Wu examines were in search of allies — critics of historical-critical exegesis and scientific ideas like evolution, they were fighting not only against anarchists and Marxists like Mao, but also liberal Christians. At stake was the question: how could China enter the modern world without betraying its identity?

Missionaries sought to respond to the chaos. As Wu demonstrates, however, as German missionaries adjusted to the new postwar realities, they displayed a kind of global consciousness. Concerned over the spread of socialist ideas in Germany, leaders of the BMS like Karl Axenfeld demanded the formation of a Volkskirche (people's church) that would speak to the spiritual needs of atomized urban dwellers that would contrast with what he dubbed the old model of a Staatskirche (state church). Yet as Wu shows, these moves within Germany corresponded to a more global moment "when calls for creating an 'indigenous church' abounded in missionary circles worldwide." With not only Germany but also China under the threat of atheistic Bolshevism, what was needed more than ever was not liberal-modernistic pablum, but rather theological fundamentals. Still, BMS leaders like Axenfeld's successor argued that even the timeless revelation of Scripture had to be embedded into "the people" (das Volk), since "peoples" (Völker) were themselves "something as timeless and ageless as the gospel itself."

This meant that the Chinese church would look different from the German church. It also made for an appealing way to square the circle that Chinese Christians had been facing apropos Christianity as an imperialist import. Pushed on by the Vatican, meanwhile, the SVD made tentative steps to transfer power to local Chinese Christians, but still refused to consecrate a Chinese bishop. By the 1930s, moreover, the BMS had, Wu writes, "turned over only one congregation to the hands of a Chinese pastor." "Missionaries," he explains, "continued to complain about the unreadiness of their Chinese congregations for independence."

All the same, the 1920s saw radical shifts in how missionaries understood Confucianism's compatibility with Christianity. BMS leaders claimed that in a world now threatened by socialism and secularism, Christians needed to make common cause with other defenders of stability—in this case, Confucians. This did not make them syncretists or liberals. Unlike their German liberal-modernist rivals, BMS missionaries never advertised Christianity as "a variation of Confucian ethics," and they remained clear that only Christianity could save China.

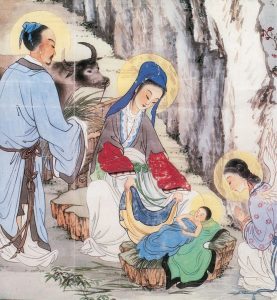

All the same, this was a considerable shift from the smug superiority of the nineteenth century. Perhaps more spectacularly, SVD journals for German audiences began reporting favorably on the life of Confucius, and "Sinicized versions of the Virgin Mary proliferated within its pages." This, too, marked a major shift. In the late 19th century, similar journals had exclusively displayed Christ and the Virgin Mary in Renaissance-style paintings and demeaned Chinese as "slit-eyed." Yet now they depicted Jesus and the Virgin Mary with those very same characteristics. Nor were these shifts purely aesthetic. In 1934, the SVD appointed its first Chinese priest, Thomas Tian, to an apostolic prefecture in Yanggu (west of Qingdao).

Wu's story ends with the tumult of the 1930s and 1940s. The BMS leaders were initially cautiously optimistic toward Hitler, seeing in him someone who would finally stand up to French and British imperialism. Yet the Nazi seizure of power soon put the BMS under immediate duress. Nazi restrictions on foreign currency outflows made it difficult to finance missionary activities abroad.

These restrictions also applied to the SVD, but because of the Catholics' more international character, they were less devastated by the new order than the BMS. Suddenly destitute (at least in China), BMS had to dramatically reduce the number of missionaries abroad. This, however, unintentionally led to the indigenization of congregations, as from 1936 onward, BMS simply no longer paid indigenous clergy and cut back on its missionary presence altogether. And only a year later, Imperial Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China, disrupting SVD's activities (parts of which had been shifted to other Catholic national societies). Here, too, the war prompted indigenization. When the Bishop of Qingdao died in 1941, Tian (the Chinese priest in Yanggu) replaced him; another Chinese replaced Tian in Yanggu.

Yet with a civil war continuing to engulf China, the future of Christianity there was still very much up for grabs. Chinese Communists ransacked the SVD headquarters in Qingdao in 1945, destroying priceless records and archives of the Society's activities. Following the CCP's victory in 1949, Chinese Protestant leaders signed a "Christian manifesto" announcing their fealty to Communist rule; two years later, movers behind the manifesto such as Wu Yaozong established the Three-Self Patriotic Church, the only tolerated Protestant organization in the PRC. In 1957, a similarly tolerated Catholic organization, the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association, was formed.

Since 1949, Western missionaries as well as scholars have debated the fate of Christianity in Communist China through the lens of control and resistance. Defenders of the Three-Self Patriotic Church and the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association view them as authentic attempts to reconcile Christianity with Chinese nationalism and anti-imperialism. Critics have attacked the Chinese who founded these groups as traitors and instead champion "people such as Wang Mingdao and Watchman Nee, who refused to join the Patriotic Church and suffered persecution and imprisonment as a result." These debates, in turn, represent a move by conservative evangelical groups to champion the (illegal) underground church movement in China today as the true soul of Chinese Christianity.

In the closing chapter to From Christ to Confucius, Wu sidesteps these debates by instead focusing on the choices of two Chinese Christians, the BMS pastor Ling Deyuan and the scholar Chen Yuan (who ran an SVD-sponsored Catholic University of Beijing, now Fu Jen Catholic University in Taiwan). Chen (1880-1971) was a prolific scholar on the religious history of China, and ran the Catholic University in a spirit of Sino-Western cooperation, but he later came to denounce the SVD missionaries running the University as imperialists and renounced his subtle scholarship. Ling, meanwhile, was a faithful pastor, but later grew sympathetic to the Communist cause and became a CCP cadre in southern China. He would later downplay his Christian background and died before the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

For Wu, the story of these two men's lives illustrate the ambiguities that Chinese Christians faced in the 1940s. 1949 brought with it major ruptures. But it also illustrated how the discourse of "indigenization" could be used not just by foreign missionaries but also the CCP to put forward a vision of a China free of foreign influence and rooted in local communities. Precisely because the CCP trafficked so heavily in these discourses, a man like Ling with organizational skills could be as useful as a Communist to the Party as he had been a Christian to BMS. For Chen, meanwhile, his work at the Catholic University had offered an institutional space to shelter students (and himself) from the government, and, later, the Japanese. Missionary institutions provided a kind of fortress from the vagaries of life in China, an unaccountable and often absent central state, and foreign imperialism. However, once the Communists filled this vacuum with a stronger state opposed to foreign imperialism (and limited toleration for Christians), there was less need to rely on suspect foreign sources.

While the story of not only the survival but also the underground flourishing of Christians in China from 1949 to today is still perhaps yet to be written, Wu's account explains the paradoxes in the religion's journey from the Opium Wars to 1949. Having explored some of the contours of that story with him, we move in our final section to discuss his current research interests and readings.

Even as Wu has only just completed From Christ to Confucius – as well as an article drawing from the same research agenda in a recent issue of The American Historical Review – he is already hard at work on a second project. He jokes that he wanted to move away from the subject of religion after writing the first book, and decided to write on the history of global health workers in East Asia from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth century. However, it has swiftly become clear how deeply embedded missionaries were in the making of public health institutions in China during that period. "During my research for the book," Wu jokes, "I would often set aside the files on health because they didn't seem relevant to the story I was telling."

Now, however, he finds himself returning to many of those same files to explore how first missionaries and, later, international institutions like the League of Nations constructed leper colonies, sought to eliminate syphilis, and to improve public sanitation more generally. Medicine was, like religion, a key arena in which Europeans and indigenous modernizers made claims about what it meant for a society to become truly "modern." The story of how would-be Samaritans brought modern medicine to China – while also bringing back a fair bit of received wisdom about Chinese medicine to Europe with them – thus has implications beyond the specifics of the German-Chinese encounter. It reveals, he hopes, the circulation of medical authority in a global arena. Wu's research for this second project has been supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, and future research will likely bring him back to Taiwan and other research sites in East Asia.

While the present moment thus finds Wu hunched over many an archival folder on German secular and religious health institutions in China, we ask him what he has been reading in the field of global history. In terms of methodology and approaches, he mentions Sebastian Conrad's recent book What is Global History? (featured in a recent interview with the Toynbee Prize Foundation), as well as 2017 Toynbee Prize winner Jürgen Osterhammel's The Transformation of the World.

Beyond these more general works, Wu has also been re-visiting the British historian Meghan Vaughan's 1991 book, Curing Their Ills, on colonial medical missionaries in Africa. In the field of Chinese history, he has been reading Sean Hsiang-Lin Lei's Neither Donkey Nor Horse: Medicine in the Struggle over China's Modernity. Lei's book explores how the Chinese public health system in China today was made in part through its engagements with the wider world during the late Qing and the Republican period.

As our conversation draws to an end, we are grateful to Wu for exploring the contours of intellectual and theological exchange between Europe and China. With perhaps 30 million Christians in China today, the story of that religion's extra-European trajectory is far from over. And as Christian churches more generally face the challenges and opportunities of growing congregations and priests from the Global South, the story of how German missionaries encountered, educated, and were eventually replaced by their Chinese counterparts remains of obvious relevance. We are grateful to Albert Wu for shedding light on this story, and congratulate him on the publication of From Christ to Confucius: German Missionaries, Chinese Christians, and the Globalization of Christianity, 1860-1950.