The Emancipators: A Conversation with Amalia Ribi Forclaz on The Politics of Anti-Slavery Movements and European International History

When did slavery end? For American or British readers of the Global History Forum, the answer to this question, at least answered within the framework of their respective countries, is easy. Human chattel slavery ended in the United States, we are told, in 1865 with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, while the more enlightened British abolished slavery within the British Empire in 1833.

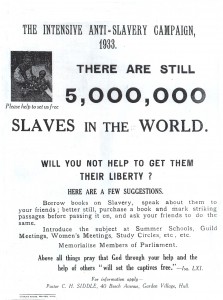

Yet globally, the phenomenon of chattel slavery (humans-as-property) and related forms of exploitation, like sex trafficking or the trafficking of children of course persisted long after slavery was abolished in Britain and the United States. Slavery is today illegal in every country in the world, but modern anti-slavery organizations reckon that there are still at least 10 to 30 million people in the world who are owned by other humans, to say nothing of much larger numbers of persons de facto enslaved through some form of debt bondage (itself legally abolished in much of the world, but still present). We may regard slavery through black and white images of plantation labor, in short, but slavery remains a big business today, with estimated global activity amounting to $35 billion, more wealth than half of all countries existent today.

Slavery must end—try finding someone who disagrees with this. But as Amalia Ribi Forclaz shows in her new book, Humanitarian Imperialism: The Politics of Anti-Slavery Activism 1880-1940, the distance between ambition and reality, not to mention the thorny political questions that the move to eliminate slavery everywhere in the planet raises, is not new. As Ribi shows in her book, late 19th and early 20th century activists were united, too, on the need to eliminate slavery in the world, especially in the African continent for which so many Europeans were scrambling at the time. By the 1920s and 1930s, the campaign against slavery in Africa brought together Catholics and Protestants, Britons and Italians, liberals and fascists, and many others, and found serious institutional backing both through the League of Nations and European states committed to the cause.

By the late 1930s, however, the international movement had fractured over the Italian invasion of Ethiopia—remembered in retrospect as a breakdown of the League's collective security function, but justified by both Italian Duce Benito Mussolini and many an anti-slavery activist in terms of eliminating slavery in that independent African kingdom. The dream of a world without slaves captured the imagination of many, but, as Ribi shows, it raised intractable questions about the place of European humanitarian action in a world that would be not only post-slavery, but also post-colonial.

By the late 1930s, however, the international movement had fractured over the Italian invasion of Ethiopia—remembered in retrospect as a breakdown of the League's collective security function, but justified by both Italian Duce Benito Mussolini and many an anti-slavery activist in terms of eliminating slavery in that independent African kingdom. The dream of a world without slaves captured the imagination of many, but, as Ribi shows, it raised intractable questions about the place of European humanitarian action in a world that would be not only post-slavery, but also post-colonial.

We were pleased to connect with Ribi, who is an Assistant Professor of International History at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, over the phone recently to discuss her new book, its lessons, and its relevance to a world in which slavery remains—as an economic phenomenon and moral outrage, if not to the same mobilizing extent it did during the years that Ribi's research focuses on. How did this waxing and waning take place, and what might it tell us about the history of humanitarianism? These and other questions were on our mind as we spoke with Amalia for this installment of the Global History Forum.

We begin our conversation with a brief discussion of Ribi's road to the discipline of history. Born and raised in Bern, Switzerland, Ribi was exposed to history from the get-go: her father was a historian and books played an important role in her upbringing. Her first love, however, was music, and she received serious training toward becoming a professional concert pianist. Inspirational teachers intervened. Doing her undergraduate work in Bern, Ribi had the good fortune to be taught by historians like Madeleine Herren-Oesch and Stig Förster, who introduced her to the field of international and of British imperial history. Working as an undergraduate research assistant in one of Herren-Oesch's projects, the multilingual (German, Italian, French) Ribi began traveling to Geneva to do some work in the League of Nations' Archives. "Madeleine was a pioneer in those archives," remarks Ribi, and credits her former professor with opening her eyes to the possibility of what could be done through stints in Geneva's holdings.

Avid to gain a better knowledge of English and to feed her growing interest in British imperial and global history, Ribi took the opportunity of an Erasmus stay in the United Kingdom, where she studied for her Master's degree at the School of Oriental and African Studies. There, coursework with scholars such as William Clarence-Smith, David Arnold, and Richard Rathbone brought her more and more into the mainstream of historical scholarship on empire, Africa, and slavery. An encounter with African historian Suzanne Miers, an expert on slavery in the twentieth century further cemented Ribi's interest in the field.

Attracted to the less hierarchical organization of academic life and doctoral education in the United Kingdom (compared to Switzerland), Ribi eventually decided to stay in Britain to pursue her doctoral work. The award of a Berrow Foundation scholarship at Lincoln College enabled her to read for a D.Phil., advised by the historian of Africa Jan-Georg Deutsch. Oxford drew her in particular because of the rich collections of anti-slavery societies stored at Rhodes House. But her initial interest in worked with these collections, indeed anti-slavery as a topic at all, originally raised eyebrows. By the mid-2000s, the assumption was that working on anti-slavery societies meant 1970s-style social histories, grounded in a single national context.

But here was where Ribi's academic and linguistic background came in. She knew, from her earlier undergraduate work in the League of Nations Archives, that anti-slavery organizations had operated transnationally, not least by lobbying the League of Nations extensively. Such activism led to the institutionalization of slavery as an international issue in Geneva, and as we have seen through previous Global History Forum interviews, the League even undertook extensive inquiries into what was then called "the traffic in women" — sex slavery, in our modern parlance. At least for the early 1920s, when the League of Nations' anti-slavery commissions still accepted information from outside groups, the links between the British Anti-Slavery Society and Geneva were tight, and many of the League's initial work on the issue was heavily influenced by British concepts and intuitions.

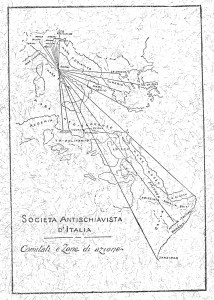

While doing research in the rich and well preserved collection of Anti-Slavery Papers in Rhodes House, Ribi became aware that Italy had its own extensive network of anti-slavery groups. The narrative was not as well-fleshed out here as for the British Empire, true. There was no equivalent of the abolition of the slave trade within the Empire, of course; not only did Italy not have an empire at the equivalent points in the nineteenth century, but of course Italy was not even a state itself until the 1870s. When Italy did in fact obtain a serious overseas colonial empire, moreover, it was decades later, in the 1920s and 1930s, through possessions in what is today Libya, Ethiopia, Somalia, Albania, and elsewhere. Yet thanks to the Vatican's efforts to achieve Catholic conversions in Africa throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, more and more Italian Catholic groups opposing the slave trade sprang up in Italian society. "There is," explains Ribi, echoing the words of a new groups of Italian imperial historians, "a colonial culture even in liberal Italian politics. Any division we might make between liberal and fascist imperialism in Italy is one of scale not of approach."

By the mid-1920s, moreover, an earlier generation of anti-slavery activists less interested in fascist politics were replaced by a younger generation of anti-slavery, pro-imperialist organizers who sympathized with the Mussolini regime's aims to rebuild the Roman Empire through territorial conquest in the Mediterranean and East Africa. Ethiopians, for example, had to be liberated from backwards practices such as slavery if they hoped to ever join the modern world. In what must come as the most bizarre episode of Italian groups' engagement in East Africa, Italian anti-slavery organizations sponsored the construction of so-called "Freedom Villages"—manufactured settlements of freed Ethiopian slaves inside of Ethiopia living and working on communes under Catholic missionary control.

Yet it was the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935-1936 that showed how different the Italian politics of anti-slavery were—and how fractious and political seemingly "humanitarian" movements like anti-slavery could become. The Italian regime justified its invasion of Italy largely on the grounds of liberating Ethiopians from themselves and eliminating slavery. One popular song at the time, commissioned as part of a hit parade for the regime, went:

If you look down from the plateau on to the sea

little black girl, who are a slave among slaves,

you will sea, as if in a dream, lots of ships

and a tricolour waving for you!

Little black-faced girl, pretty Abyssinian,

wait and hope as the time approaches,

when we will be near you

we will give you another law and another king.

While the invasion shocked international opinion, Italian anti-slavery groups hit back hard, championing the annexation of Ethiopia on the grounds of humanitarian anti-slavery activism and accusing their opponents elsewhere in Europe of having a limp consciousness when it came to the bestial practice of slavery under Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie. The Vatican rejected Selassie's calls for the League of Nations to intermediate in the crisis, noting that Geneva embodied the corrupt laws of man—in contrast, ostensibly, to the blend of Italian civilization and Catholicism that Mussolini's colonial venture would bring to Africans. The politics of anti-slavery, Italian colonial nationalism, and Catholic proselytization had become one. It it the tension here between humanitarian activism and perhaps the single event that delegitimized the League of Nations' collective security arrangements and these humanitarian motives is what gives the book its title.

Ribi was beginning her trips to the archives at an auspicious time. Already when she started her research, she notes, there was something of a pushback against the picture of interwar Europe as a time when efforts towards international cooperation broke down — "the lights that failed," in the words of Zara Steiner's influential 2005 book on European internationalism. Recently, historians such as Patricia Clavin and Susan Pedersen have convincingly shown how forms of international cooperation persisted or even took off well into the 1930s. However, Ribi remarks, it's crucial for the historian to examine non-liberal or illiberal internationalism in addition to the projects championed along the shores of Lake Geneva. "Fascists," she reminds us, "were internationalists too." Only by firmly situating the Italian anti-slavery story alongside its other European counterparts can we see the similarities and differences in these groups' embrace of "the international"—and what difference the Fascist turn made in how these groups envisioned international coöperation.

As Ribi explains her journey to her conclusions, we ask her about her research process. What advice, we ask, would she have for aspiring scholars of international topics? Her advice: curiosity, flexibility, and a willingness to break with the contemporary assumptions about what the "hot" research agenda of the day is. While more recent pilgrims to the Palais des Nations will likely leave with fond memories of the League of Nations' Archives' reading room, Ribi notes that during her first days working there, the room was located in another, much dingier, space, than the current generous rooms those research facilities occupy. Echoing fellow Global History Forum interviewee Susan Pedersen, she underscores how "off the map" the League's Archives were when she first began to work with them. What might be the sought-after archive of the moment when you start your M.A. or PhD may not be it when you finish, in other words.

She also notes that one challenge—and joy—of pursuing international history scholarship is the fragmented, multi-archival, and multi-lingual nature of sources one has to put together. Working in the archives of the Affari Esteri and the (now closed) Istituto italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente in Rome, she recalls, she had to adapt her research schedule to the moods and disposition of the staff. Sometimes, collections and even institutions would close without further notice or weeks would go into following a lead on the archives of one organization, only to yield little. These hiccups, however, led Ribi to less obviously relevant collections like the Vatican Archives or the archives of the Missione Consolata, which shed light on the story of Catholic and Protestant competition over proselytization during the "Scramble for Africa," a kind of religious cold war as European empires carved up the Continent. Anti-slavery groups and Church groups kept in close communication with one another, helping Ribi trace the outlines of a network of self-declared humanitarian actors deeply engaged in pro-imperial activism. Put in other words, the big, intimidating list of archives at the end of books like Ribi's represents the product not of intelligent design, but of much stumbling in the dark, or, as the case may be, Rome.

One might ask a critical question of Ribi here: what role for African agency, for Ethiopian voices, is there in her story? Haile Selassie, she explains, was aware of his dilemma as head of a state that was massively weaker than Italy. Reacting to increasingly sensationalist and widely publicized accounts of the barbarity of Ethiopian slavery, he invited British anti-slavery activists to Ethiopia to inspect the state of the country, but, unwisely did not allow them to leave the capital, Addis Ababa. Even had he, however, she explains, there was a disturbing tendency among British anti-slavery activists to give credence to Italian reports of persistent slavery in Ethiopia. When Italy finally exploited a moment of particular friction in the international system to invade the country, many embraced the Italian campaign as a chance to breathe new life into the anti-slavery cause internationally, ignoring the Italian's use of chemical weapons as it butchered the people it claimed to be liberating.

Obviously, however, British internationalists' opinion was not monolithic. Britain's League of Nations Union (a civil society group designed to promote internationalism at the grassroots level) naturally worried about the precedent the Italian chemical attacks would set for European collective security going ahead. Haile Selassie himself became a symbol for internationalists and anti-fascists around Europe and the world, delivering a famous speech against the Italian campaign at the Palais des Nations in June 1936.

Yet as Ribi suggests in the end of Humanitarian Imperialism, the Ethiopian adventure prompted, if anything, more chaos and fracture among do-gooders internationally than it did unity. The Italian campaign, which seemed to fuse European colonial exploitation so cynically with European discourses of liberating Black Africans, was a turning point for Pan-African movements throughout Europe and North America. Leaders of the British Anti-Slavery Society which, founded in 1839, used to have a quasi-monopoly on speaking on behalf of African slaves was surprised to find that the subaltern could, it turned out, speak. Worse, the visions that intellectuals like Marcus Garvey (based in London from 1935) and the international Rastafarian movement (which worshipped Haile Selassie as a Christ figure) had for Africa were radically at odds with the visions of trusteeship and tutelage many anti-slavery activists still held dear.

As her book shows, by the late 1930s, as London filled with these and other pro-Ethiopian activists who who put forward alternative ideas about non-colonial sovereignty and internationalism, forcing British anti-slavery activists to reconsider their aims. The outbreak of war in Europe would temporarily sideline some of these questions, but the politics of anti-slavery activism would revive again after the Second World War, in the context of the United Nations Organization, when many thought that slavery had disappeared and when the old Christian tropes motivating earlier activism no longer swelled hearts the way they had in the 1920s, much less the 1890s. As the conclusion to Humanitarian Imperialism suggests, however, the tension between national sovereignty and some form of internationalized humanitarian interest dominated debates in the 1970s and 80s, and it is ever present in debated today over trafficking.

As Ribi explains, this point about the politics of humanitarianism and national sovereignty is not merely a theoretical one. She relishes the challenge of teaching students in Geneva who do not necessarily have a background in history, but who aspire to join international NGOs, and who want to work on the anti-trafficking agenda and have a hard time viewing the work of humanitarian NGOs as anything but morally pristine. The idea that the near-permanent involvement of primarily Western NGOs into what remain technically sovereign states could be seen as problematic does not always register. Ribi tries to avoid playing only the role of the critic. Prior to starting her academic career, she notes, she worked briefly for an NGO to get an insider's view — "I didn't want to just be a negative voice," she explains.

Still, dealing with the unpunctured idealism of many colleagues there firmed her belief in the responsibility of the historian to complicate, challenge, and contradict self-satisfied narratives about transnational humanitarianism in history. During the 19th century, for example, many an anti-slavery activist overlooked or simplified the fact that many forms of "slavery" in Sub-Saharan Africa were inflected with kinship systems and networks of reciprocity in a way that made them fundamentally different from the transatlantic system. "Reforming" these systems often created new interpersonal or inter-tribal grievances that generated more trouble than the "slavery" systems they replaced. Officials and activists often turned a blind eye to forms of forced labour that were tolerated in many colonial territories. More than that, as much as anti-slavery activists and missionaries spoke in terms of freedom and liberation, the promise of citizenship and of social rights was, of course, decisively not in the cards for former slaves still within the British Empire or its mandates. So here is another point of relevance from Ribi's work: for all the enthusiasm that a turn to a concept of freedom grounded in "human rights" inspires, it may be worthwhile to keep questions about citizenship and international labor regimes in the foreground of our analysis.

As our interview comes to a close, we ask Ribi about her sources of inspiration: what books has she been reading lately? She singles out the work of Northwestern historian Helen Tilley, in particular her recent 2011 book Africa as a Living Laboratory (University of Chicago Press), which examines the Continent as a testing ground for British imperial scientific expertise. Ribi also mentions the work of Tilley's colleague (and former guest to the Global History Forum) Daniel Immerwahr, whose Thinking Small (Harvard University Press, 2015) explores the history of community development from the vantage point of a modernizing American state in the Third World—and in its own "underdeveloped" slums and ghettoes. (Immerwahr's work was the focus of an earlier Global History Forum piece.)

Fortunately, she notes, the development field is a burgeoning one, and she looks forward to such forthcoming works as Nicole Sackley's Development Fields: American Social Scientists and the Practice of Modernization During the Cold War (forthcoming), which examines postwar American development in independent India. Nor is her enthusiasm for the intersection of development with international limited to works on practice itself like those by the two Chicagoans and the Richmond-based Sackley. Ribi also highlights recent and forthcoming works by her colleagues Davide Rodogno and Marc Flandreau: Rodogno's and Heide Fehrenbach's co-edited volume on humanitarian photography, and Flandreau's forthcoming book Anthropologists in the Stock Exchange, which uncovers how Victorian anthropologists used their scientific status to manipulate the stock market.

It's to such works that Ribi turns as she breaks ground on a second project, this time on the global history of rural development titled International Organizations and the Conceptualization of Rural Development, 1920-1970. She starts from a simple premise: "Rural development began its conceptual life as a category for Europe, but since the 1970s it's shifted to the Third World." Ribi's book will aim to explore the interwar European origins of rural development as a solution to certain regions' backwardness: southern Italy being perhaps the classic case, but also much of eastern Europe and "backwards" agrarian hinterlands in wealthier Western European democracies. In taking on this research agenda, Ribi is largely in dialogue with a broader research agenda that we highlighted at the TPF website in October 2014 following a conference at Columbia University. It also puts her in dialogue with scholars of development like Corinna Unger, whose Paths to Development in India we covered this fall in the Global History Forum.

Broadly, these scholars are comfortable working in the archives of multiple international organizations, asking how it was that Europe—in an age of decolonization, above all—massively transformed the mechanisms via which capital and expertise could flow to "underdeveloped" regions across the post-colonial world. Based in Geneva, needless to say, Ribi finds herself in an envious position to carry out a research agenda that will likely draw heavily on the archives of INGO-world there. We know that we are not alone looking forward to seeing what she finds there.

•

From inaccessible archives in Rome to the shores of the Italian Empire, from the bowels of Rhodes House to the binders housed in the Palais des Nations, our interview with Amalia Ribi has, like her research itself, covered much ground. More than rejuvenating what was once seen as a staid topic in anti-slavery activism, Ribi's work shows how vibrant—and, refreshingly, dominated by female scholars—the field of European international history is these days. We thank her for participating in this interview with the Global History Forum on Humanitarian Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), and we look forward to reading more from her ongoing research agenda on rural development.