Boys on America’s Imperial Frontier: An Interview with Mischa Honeck

Histories of empire rarely center on children. As ‘subaltern’ subjects, whose ability to speak through historical sources has been rendered doubly silenced by their diminished capacity for independent action and the adult-centric nature of traditional archives, they have long been seen as mere bystanders to the extension of imperial influence across the globe. In this context, Mischa Honeck’s Our Frontier is the World: Boy Scouts in the Age of American Ascendancy (2017) takes a much-needed look at the role of children in the construction of the United States’s imperial identity. Through a detailed analysis of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA), he interrogates the interlinking impulses of youth, nationalism, and power in the first half of the twentieth century. In the process, he exposes some of the dangers that innocence can obscure, both in the present and in the past. In our interview, Dr. Honeck and I discussed these issues and the challenges that the BSA has faced in its attempts to remain current in a changing America.

— Hayley Keon

Hayley Keon: What first inspired you to become a historian?

Mischa Honeck: This is a personal question and a surprisingly hard one to answer. In a way, it all started when I was a kid and I was fascinated by history as a kind of extended fairy-tale world. It was a theme park to discovering adventure stories that made me realize that I was basically just a small grain of sand on a wide beach. It changed into something more serious when I became an adolescent, and it helped me to establish a relationship to a wider world and to explore who I was in that regard.

I went to the United States when I was a young boy. Coming from Germany, it taught me to think about what it means to stand out and be different. History became for me a problem-solving discipline that offered productive answers for dealing with issues of difference and belonging. It’s something that I carried with me until I went to university and started to understand that history might be a really interesting professional option. It has sustained me over the years, too, so it’s always been something that’s very personal to me, even as it became a profession that I also appreciate for various other reasons.

Keon: To follow up on that, you mention in Our Frontier Is the World: Boy Scouts in the Age of American Ascendancy that you were actually a Boy Scout yourself when you lived in the US. Did that impact the writing of your book?

Honeck: That is true, and that’s perhaps half of the answer to the question ‘what made me write the book.’ I don’t shy away from the fact that my motivation was partly autobiographical. I joined the BSA as an eight-year-old; I was a part of a Cub Scout pack in Oregon, and it was a formative experience in the sense that I was the only foreign-born boy in a pack of exclusively middle-class, white boys growing up in the northwest in the 1980s. I also speak openly about how I was taken aback and amazed by the displays of innocent patriotism, of love of country, of flag worship, things that my generation, the grandchildren of Nazis, had been taught to approach with a healthy dose of scepticism. Uniforms, pledging allegiance—all things that, even as a kid, I found a little bit alienating. Not necessarily bad, but alienating, and it’s something that maybe subconsciously made me think harder about who I was and where I belonged. This was something that I probably kept thinking about much longer than I initially realized after I came back to Germany.

I also speak openly about how I was taken aback and amazed by the displays of innocent patriotism, of love of country, of flag worship, things that my generation, the grandchildren of Nazis, had been taught to approach with a healthy dose of scepticism.

Keon: In the introduction to Our Frontier Is the World you describe the book as an ‘exercise in deprovincialization’ that aims to invoke the ‘local, national, and global’ as complementary (rather than contradictory) frames. How do you think this shift in thinking can impact our understanding of American power as it manifested in the twentieth-century world, and why did you choose the Boy Scouts of America as the medium through which to make these assessments, in addition to your personal experience?

Honeck: The straightforward answer is that I think the Boy Scouts of America is a great example to understand a shift that’s been going on in global history for a while. It began with the idea that global history was a rebellious movement and a protest against traditional notions of history as a discipline that should be confined within the boundaries of the nation-state. But now I think we’ve entered a new phase, which is defined by a recognition that global and national histories are not necessarily irreconcilable approaches but, instead, can fruitfully complement each other. In order to truly understand the importance of the Boy Scouts—not just for American history, but for a global history of the twentieth century—you need to understand that the organization is a cross-border phenomenon, for which both approaches are necessary to grasping fully how the Boy Scouts of America changed American society and wielded influence on the world stage.

The second part of your question—what can they tell us about the nature of American power—points to the heart of the book. My understanding is that telling the history of the Boy Scouts of America from a transnational or global vantage point offers a fresh perspective for addressing two central myths in US history: one being the myth of empire; the second one being the myth of childhood, and more significantly, what can be accomplished by bringing these two myths into conversation with one another. I argue that they are actually more interdependent than a first glance might suggest.

Keon: Definitely. I felt that your book made smooth work of addressing these two oft-overlooked issues together and using children as a lens to find American influence in places where it isn’t typically identified.

Honeck: Yes, I would agree with that, because what I think is constitutive of the myth of childhood is the notion that children are apolitical or do not belong in the scale of hard power. That’s one assumption I wanted to debunk in the writing of this particular history. The second thing is perhaps an even more widely accepted myth: that the United States achieved unprecedented impact on the world stage as a non-imperial power. This paradox has been addressed from a variety of standpoints, but it was a trajectory that I really wanted to investigate myself, not necessarily in the sense of whether the US is an empire, but in the sense of how it operated throughout much of the twentieth century.

Keon: One of my favourite chapters of your book is chapter two, which details two expeditions that took Boy Scouts to places that seemed like the ends of the earth for many twentieth century Americans: Antarctica and the plains of central Africa. So, for those who have yet to read the book, what were the purposes of these extended adventures, and how do you see these trips fitting within the wider aims of the BSA in the period between the two World Wars?

Honeck: The two expeditions you reference happened in quick succession. One resulted from the idea of two famous wildlife photographers, the hobby Africanists Martin and Osa Johnson, who wanted to promote what they were doing while also aligning themselves with key players in American society and culture, including the Boy Scouts of America. The other one was an expedition to Antarctica that was led by Richard Byrd, who was this adventurer-swashbuckler figure comparable to Charles Lindbergh and other famous early-twentieth-century explorers.

On the surface, the purpose of both of these trips was to market the Boy Scouts of America as an institution of wholesome recreation for young American males at a time when middle-class educators were increasingly concerned that modern consumption entertainment was making not just working class youth but also middle class youth increasingly effeminate; that the allures of dating, gambling, and other “problematic” recreation activities were not conducive to making young men into effective citizens. The idea was that, by promoting these exciting adventures, young boys and adolescents who were starting to fall out of love with the Boy Scouts would reconsider and maybe choose the BSA as an organization that could offer exciting forms of socialization for boys. That was one goal.

The other goal had more to do with what it meant to grow up as an American in a country that was starting to embrace its global role despite the fact that, at the level of government and state-building, the 1920s is often described as a period of isolationism. That is something else that I wanted to question, because in society and on the grassroots level, there was a flurry of engagement with the wider world during this time. I think the Boy Scouts bear out that fact. It’s not just in the chapter where I talk about the expeditions: I think the international Boy Scout gatherings called ‘jamborees’ are also great examples of how average Americans young and old saw the world as an increasingly important part of their lives, and how the world appeared to rely more on American involvement.

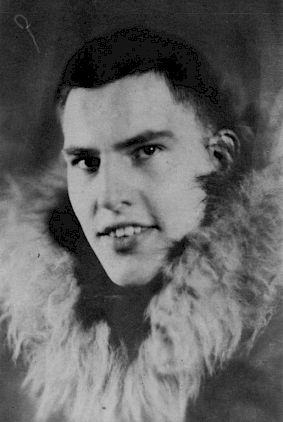

Keon: That’s really interesting. Another thing that really struck me in that chapter was the way that one of the Boy Scouts who participated in the Antarctica expedition, Paul Allen Siple, became the focus of an intense re-imagining in the American press before he had even left. I thought that was fascinating and revealed interesting connections between the BSA, American media, and this idea of the American nation.

Honeck: Yes. Siple became this cross-generational point of reference, both for the boys who idolized him (because he was a darling of the press, at least for a while) and for the men who saw in Siple an almost idealized younger version of themselves. In a way, he encapsulates the promise of something that I call ‘boyification.’ That is where I think my book departs from previous studies of the BSA, which often portray Boy Scouting solely as a conduit for teaching young boys to become men, citizens, and leaders. But I think this is actually a two-way street, because I believe the Boy Scouts also functioned as an important site of regeneration for middle-aged and older men, who embraced it as an opportunity to re-fashion themselves in ways that allowed them to shed attributes of manhood that were more problematic, even sinister. Becoming youthfully rejuvenated in the company of boys was a sort of purification strategy, a performative mechanism to deflect from the more toxic aspects of imperial manhood that had emboldened others to question the supposed innocence of American power.

I believe the Boy Scouts also functioned as an important site of regeneration for middle-aged and older men, who embraced it as an opportunity to re-fashion themselves in ways that allowed them to shed attributes of manhood that were more problematic, even sinister. Becoming youthfully rejuvenated in the company of boys was a sort of purification strategy, a performative mechanism to deflect from the more toxic aspects of imperial manhood that had emboldened others to question the supposed innocence of American power.

Keon: That was another aspect I really enjoyed in your book: that the pressures of making boys, making men, and making the nation all run together. Did you find during your research that there was a lot of evidence of Boy Scouts trying to push against the ideas of these men, who were also trying to use them for their own re-creation of self? Or did you find that the Boy Scouts were willing to participate in this boyification process?

Honeck: This goes straight to the question of agency. What does it mean to have agency as a boy in a world where the hierarchies favour adult decision-making? In that particular area, boyification and boy-manhood forces us to rethink what it means to have agency as a young person. This is a conversation that has been going on in the field of childhood and youth studies for a while. Where I come out is that, within the organization, at least according to the overwhelming evidence from sources that reveal something of what the boys thought and did, compliance and over-identification with the BSA’s ideological and political agenda were much stronger than the urge to resist or to oppose. Where I think you find opposition was oftentimes beyond the purview of the BSA, in all of these young people who were uninterested and who saw the Boy Scouts as strange and odd and, in a way, contrary to their ideas of what it meant to be a boy. That’s where you find the resistance aspect.

Within the organization, I think the that the question of agency becomes more complicated when you look at the role that non-white youth played, which I talk about in chapter four. Looking at issues of race and coloniality in the Boy Scouts, I try to emphasize that the intentions and ambitions of boys of color who became Boy Scouts were not identical to those of the majority white youth. This is not surprising in light of the historical barriers of oppression and discrimination that separated the live worlds of white and non-white youth across the twentieth century. There you probably have the most tension between the organization’s goals and the practices and intentions of scouts.

Keon: It’s interesting that you don’t see as much ‘youthful resistance’ in the BSA as a whole. I think that’s something that has been fetishized in the field of childhood history in general: that young people resist, that they are always fighting the adults in power.

Honeck: Absolutely. If you look at the paradigm shifts in the field, each and every turn starts with a gesture of protest and resistance. When these turns age, when they mature, they often lose—not necessarily that critical edge; they remain critical interventions—but they become critical interventions that understand that it’s often not a black or white issue; that, oftentimes, it’s much more about trying to reconcile different strands of thinking. In the case of the Boy Scouts, just because the boys’ individual objectives and goals often matched those of adults doesn’t mean that they weren’t capable historical subjects. This is something that I think early discussions of agency often downplayed: that to be a historical subject, you don’t necessarily have to resist. Sometimes you can inscribe yourself into power structures as an ordinary foot soldier and still be an incredibly effective player.

Keon: Building on this question of childhood history, one of the biggest problems in the field is, of course, finding sources. When you were doing research, did you find that the fact that these boys were participating in the BSA made it easier to find them within traditional historical archives?

Honeck: There are always gaps and silences in the records. It’s hard to ignore that, and I would be the last person to trivialize what it means to recover children’s voices. At the same time, the outlook is not necessarily that bleak. Maybe this is specific to studying youth in organized settings, because obviously adults had strong motivations to record the mobilities of their youthful subjects. The reason for this—and this is where I agree with conventional scholarship—is that the Boy Scouts were an organization that sought to discipline and control young people as much as they wanted to also animate and liberate them from what they identified as corrosive influences on young manhood. Because of that, there’s plenty of interesting commentary on what young people did and what they supposedly thought within scouting. This is not specific to the Boy Scouts of America—I think this is true for almost all of the major youth organizations of the twentieth century. That also compelled me to reconsider what it means to recover the voice of the child, because sometimes adult-authored sources contain the fingerprints of young actors as well. They also reflect things that young people did and can serve as a lens that can help approach young people as subjects within certain fields of academia.

...the Boy Scouts were an organization that sought to discipline and control young people as much as they wanted to also animate and liberate them from what they identified as corrosive influences on young manhood. Because of that, there’s plenty of interesting commentary on what young people did and what they supposedly thought within scouting. This is not specific to the Boy Scouts of America—I think this is true for almost all of the major youth organizations of the twentieth century. That also compelled me to reconsider what it means to recover the voice of the child, because sometimes adult-authored sources contain the fingerprints of young actors as well. They also reflect things that young people did and can serve as a lens that can help approach young people as subjects within certain fields of academia.

Moreover, I realized that even local run-of-the-mill newspapers can be wonderful sources to get a better grasp of how young people expressed themselves. Boy Scouts wrote tons of letters home when they were going abroad to attend a jamboree, for instance. There were entire columns reserved for young people making themselves heard. As letter-writers, they commented quite confidently on foreign and domestic affairs. So, I think newspapers are, perhaps, an under-appreciated resource to get a general understanding of discourses surrounding race, gender, citizenship, and nationalism that many underage people at the time were participating in. This can help us recover young voices to a greater degree.

And a last point on that question. Something I feel I should have done more, but what I hopefully at least hinted at was the potential that resides in pursuing oral interviews. In my case, I did a couple of interviews with former ‘army brats’ who were stationed abroad in Japan and West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s. My interviewees were happy to share their memories about being a Boy Scout at a US army camp in West Berlin, Tokyo, Osaka, and Korea. These are precious memories and precious texts that historians can investigate. Of course, we all know the limitations and dangers of relying too much on oral history, but again, if we are pragmatic about it and have the right methodological tools to separate history and memory, I think there’s much to gain from taking oral history seriously as a resource to get at children’s voices.

Keon: Moving back to the idea of America: your book begins amid a high of early-twentieth-century colonial fervour and ends with something like its hangover, as the United States (and the BSA) are forced to grapple with an American public cut by racial, religious, and political divisions in the wake of the Cold War. What were some of the key challenges that the BSA faced during this time, how did the organization fare, and what might their (semi-)fall from grace say about the United States at the end of the twentieth century?

Honeck: You’re talking about the epilogue of the book, and I think it’s (hopefully appropriately) titled ‘The Woes of Aging.’ It details the painful realization among the BSA’s leadership and a substantial part of its membership that the old formula of masking and maintaining empire by tapping into this redemptive quality of boyhood had run its course. This was the result of several dramatic transformations in American society and politics that converged in the late 1960s and early 1970s: one being the bitter controversies surrounding the Vietnam War and the other being the social movements of the era—civil rights, sexual liberation, and women’s rights—which ran counter to this idea that the rejuvenation of white Anglo-Saxon manhood is the only promising course to chart in order to keep America strong. This notion came under increasing attack at the time.

Then there was the factor of demographic change. The BSA’s golden age (at least numerically) was the 1950s and 1960s, with the baby boom and all of these young boys streaming into extracurricular organizations, including scouting. That demographic boom lasted until the start of the 1970s, and then birth rates started to come down again. Statistically, this meant that there were fewer young people to recruit. That’s just a banal fact, but I think it’s important to recognize, as well.

For the organization, this created several pressure points, and I think the 1970s are a reflection of the BSA struggling to remain relevant and to remain culturally young. This is expressed in the organization’s decision to rebrand and change its name from the Boy Scouts of America to Scouting USA, which carries a lot of symbolic weight because it seems to suggest a greater openness to co-educational ideas of raising young people. But, still, this downward spiral was hard to stop, and within the span of ten years, the organization lost one-third of its members. That was a membership shock that the BSA never managed to recover from. I’m not going to say it spelled doom, but after one crisis seemed to end another began. You had the 1990s and the culture wars, then you had the string of bad news for the BSA from all of these lawsuits, and finally you had the recent uncovering of scandalous behavior within the ranks of scoutmasters in terms of sexual abuse lawsuits and court rulings. This is also borne out by the fact that the present USA suffers a degree of polarization that is almost without precedence in history. The Boy Scouts are basically torn apart by these two competing urgencies: to cater to the changing interests and expectations of young people, who may have become more “liberal” than previous generations, while also having to appease their conservative base, who do not want to surrender certain ideas about manhood and nationalism. This has also resulted in several smaller successions and rival organizations.

Just recently, I read about young BSA members becoming involved in lots of charity work and neighbourhood projects in the USA trying to help older people cope with the pandemic, so it remains to be seen if this could be a moment of civic rebirth for the organization. Regardless, I don’t think that the Boy Scouts of America will necessarily disappear, but I don’t see them regaining that uncontested hegemonic position they had in the 1950s and 1960s, because that was a very particular moment in the history of American power that I don’t think will resurface in the twenty-first century.

Keon: Your book ends with the weight of a warning: that, in your words, ‘cherishing the authenticity of boyhood should not blind us to the dangers of powerful men governed by the narcissism of adolescence.’ In that context, what parallels, if any, do you see between the period you research, and the United States of the present, and what lessons do you hope readers take away from your text?

Honeck: That’s the one-million-dollar question here, and that touches upon the very complicated subject of history as a mode of intellectual intervention. I think historians have an obligation to occasionally step out and offer informed public commentary on what history can tell us about where we stand as a society and as peoples. My hope is that readers who go through the pages of Our Frontier Is the World will understand that there is a danger in becoming too infatuated with the idea that boys or boyhood is this site of innocent play and adventure—that it can do no wrong. It’s also a place where adults can claim the mantle of youth, its energy, vitality, and dynamism. It’s always a trade-off, and it comes at the price of hiding things about themselves that may seem more problematic and unpleasant than youth’s seeming inoffensiveness might suggest. I’m not going to name names here, but there is a practice of tugging away, or cloaking ugly consequences of certain actions, that is entailed in the idea of becoming youthful or boyish. It’s our responsibility and our obligation to look at these phenomena critically and to treat them as performances. While they emphasize certain aspects of our lives, they also hide or make invisible others that require equal attention.

Keon: Can you tell me a bit about your current/future projects?

Honeck: Maybe it’s not exactly a follow-up book, but I’m trying to expand on this theme of youth as more than just a life stage leading up to the prime of life, to adulthood. It’s also something that societies and individuals try to embody and re-embody for different purposes at various points in the lifecycle. The idea that ‘age’ and ‘aging’ are simply linear developments is something that I want to critique and challenge by showing how rejuvenation in particular emerged as powerful medico-cultural tool for people who are not biologically young to claim aspects of youthfulness to oftentimes sustain existing hierarchies and privileges. Rejuvenation fascinates us, I believe, because it upends common conceptions about aging and time. It conjures up a horizon of unfading physical and mental powers, a place where the linearity of time is suspended and subjected to human control.

My ambition is to write a long durée history of rejuvenation in the United States from the founders to the transhumanists in the twenty-first century. I want to look at how youth and youthfulness have been deployed by various social groups in pursuit of the liberating qualities associated with youthfulness, while also excluding marginalized populations from this very promise. Much of our profession has become incredibly sensitized to demarcations of race, class, gender, and sex—and rightfully so—but still tends to treat age like a neglected stepchild. My work can hopefully help to correct this imbalance.