Brazil, Portugal, and Authoritarian Development: An Interview with Melissa Teixeira

During the interwar years, intellectuals across Europe and Latin America sought alternatives to both liberal capitalism and revolutionary socialism. Among the most ambitious of these experiments was corporatism—an effort to reconcile class conflict, stabilize economies, and moralize markets through state-managed cooperation between capital and labor. Once heralded as a “third path” between capitalism and communism, corporatism became the ideological foundation for authoritarian regimes in Brazil and Portugal under Getúlio Vargas and António de Oliveira Salazar.

In A Third Path: Corporatism in Brazil and Portugal (Princeton University Press, 2024), historian Melissa Teixeira revisits this forgotten history, tracing the global and transnational circulation of corporatist ideas and their enduring legacies in twentieth-century economic governance. Moving between intellectual history and political economy, Teixeira reveals how corporatism promised social peace and economic justice even as it reinforced hierarchy and curtailed democracy.

I spoke with Melissa Teixeira about the origins of corporatism, its transatlantic networks, and its afterlives in postwar developmentalism—along with what this history can teach us about the fragility of liberal democracy in times of crisis.

— Sergio Infante, Yale University

SI: Historian Patrick Iber once suggested that while “many intellectuals from Latin America sought ways out of Cold War binaries,” a good number of these thinkers “were also responsible for inviting the Cold War in, hoping to use it to advance their interests” (Neither Peace nor Freedom, Iber, 15). Your book examines one attempt to steer a course between capitalism and communism. What was corporatism?

MT: One of the biggest challenges in writing A Third Path book was to define “what is corporatism” and explain what distinguished this “ism” from other political and economic programs. Part of what makes “corporatism” so hard to define is that this ideology does not have a single founder, canonical text, or country of origin. Its meaning and practice have evolved over centuries and across many regions. Even the fiercest promoters of this system often disagreed on what it meant or how to put it into practice, coming together more in opposition to other ideologies than cohering around a shared vision. Rather than impose a single fixed definition, my aim is to trace the evolving meanings of corporatism alongside its many contradictions. One of the central puzzles in writing A Third Path became to explain how such a vague and variable set of ideas and practices became such a powerful ideological force in the 1930s.

Even so, a baseline definition is still useful. The simplest definition of corporatism is perhaps the one that the dictators, intellectuals, and industrialists who endorsed this ideology championed: corporatism as a third path between laissez-faire capitalism and the command economy associated with communism, and also a third path between political liberalism and the highly centralized totalitarian models of the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany. There is, of course, an inherent problem in defining an ideology in terms of what it is not. In the 1930s, Brazilian and Portuguese conservative intellectuals and political officials were keen to defend their program as neither liberal nor socialist, neither laissez-faire nor state controlled. But this emphasis on neither/nor still leaves us with the question: what is corporatism?

Corporatism is a system by which society is organized according to social and professional groups (labor unions, farmers guilds, and industrial associations) so that the state can regulate relations between different classes and different economic sectors in pursuit of social peace and national development. As an example, one especially relevant to how the Portuguese corporatist model worked, in a corporatist society, wheat farmers would join a grémio (guild or trade union) created by or legally recognized by the state. This association would work in coordination with state agencies to regulate this sector by establishing price guidelines, production quotas, quality standards and it would also deliver welfare benefits to members. In theory, all sectors in a given society would be organized in a similar fashion, although in practice, the design and implementation of corporatist policies remained uneven and incomplete across the many countries that experimented with this system. Still, a core principle endured: rather than directly controlling economic production or leaving it to market forces, the state exerted direct and indirect influence over professional and sectoral associations to regulate the economy and shape labor relations.

SI: This baseline definition of corporatism leaves something out that is key to explaining why this system appealed to the authoritarian leaders in the process of consolidating power in Brazil and Portugal in the 1930s. Corporatism had a centuries-long trajectory in Catholic and conservative intellectual circles, no?

MT: Yes! It’s important to remember that corporatism was not a totally new ideology in these years. Rather, modern corporatism emerged as an attempt by conservative, Catholic, and right-wing groups to reinvent and modernize an older system of representation that had defined the medieval guild system and the imperial or monarchical systems of the early modern period in which a person’s profession and social standing determined their rights and privileges.

This was a world in which society was organized according to a fixed social hierarchy. The corresponding economic system was one defined by a guild system of controlled entry into a particular profession, and, for the major European empires, a mercantilist system in which monopoly companies were given special privileges to trade in certain goods and markets. These are, of course, broad simplifications of what the world looked like before the post-1789 revolutions in France and across the Americas broke imperial bonds and repealed the corporate system of economic controls and privileges—revolutions inspired by the rise of liberalism and ideals such as individual rights, direct representation, and free trade.

What is key to understanding modern corporatism, however, is that conservative and Catholic intellectuals in Brazil and Portugal viewed the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as periods of stagnation and instability—caused, in their view, by the failures of liberalism and the destabilizing effects of global market integration through free trade. They argued obsessively that liberalism was “out of place” in their societies, and that the economic and political models that may have worked (by some measures) in Great Britain or the United States had led their own societies down a path of decline. And so many in Brazil and Portugal became nostalgic for a more hierarchical, controlled, and imperial model of organizing society because they hoped that a return to older corporatist structures might restore order and stability.

SI: The Brazilian and Portuguese thinkers you study were “inviting in” a lot else besides the Cold War, to amend Patrick Iber’s phrase. Tell me about the transnational network promoting this Catholic, organicist vision of society.

MT: Corporatism was both a global and a transnational phenomenon: global in its implementation, as corporatist policies and institutions emerged across diverse national contexts during the interwar decades; and transnational in its development, as its ideas evolved through the cross-border circulation of legal models, economic theories, and institutional practices. To trace this evolution, I follow a loose network of jurists (law professors, legal experts, justice ministers, etc.), writers and intellectuals, economists, bureaucrats, and public officials who traveled—or whose writings traveled—between Brazil and Portugal, while also exploring some of the debates, exchanges, and conversations that connected them to their counterparts in Fascist Italy and the United States during the New Deal. I am not solely focused on the high-profile figures who shaped these transnational networks; ultimately, my aim is to understand how the transnational circulation of ideas and policies influenced national policymaking. In many ways, this became a project in writing an intellectual history of the state, or how corporatist ideas informed government efforts to organize producers and discipline supply. To that end, I also highlight the work of mid-level bureaucrats who were responsible for overseeing day-to-day policymaking and dealing with problems of enforcement.

With corporatist experiments taking hold across Europe and Latin America in these years, I should also say something about my choice to focus on the connections and exchanges between Brazil and Portugal. The two nations might have diverged in size, geography, and population demographics, but intellectuals and political leaders in both countries seized on their shared Portuguese language and legal culture and rehabilitated their past imperial heritage to make their case for why political and economic liberalism was ill-suited to these societies. In both countries, political and economic elites were anxious about their nation’s economic stagnation relative to others, and this shared concern drew them into conversation. They wrote about the widening gap between their agrarian societies and the industrialized United States. They blamed liberalism (with its insistence on free trade and free competition) for why their countries fell behind, pointing to their comparative disadvantage in global trade. Portuguese and Brazilian intellectuals also instrumentalized their shared imperial past and mobilized historical arguments; they insisted that corporatism offered a modernized update to the medieval and colonial forms of governance that had existed hundreds of years prior to the so-called importation of liberal ideas from France or Britain.

But this transnational lens also reveals a central contradiction in the corporatist worldview. Brazilian president-turned-dictator Getúlio Vargas and Portuguese Prime Minister-turned-dictator António de Oliveira Salazar framed their Estado Novo regimes as national revolutions—rejections of toxic, foreign, liberal ideologies and exploitative, volatile international markets. Their embrace of corporatist policies aligned with the broader interwar turn toward nationalism, protectionism, and economic self-sufficiency. Yet these corporatist experiments unfolded within a profoundly transnational context. One of the central challenges in writing A Third Path was to show how a project about national sovereignty and renewal was, in fact, shaped by transnational conversations, debates, and exchanges. By paying attention to both the nationalistic and transnational impulses at play, I recover how corporatist ideas circulated in multiple and unpredictable directions—and how they were translated, appropriated, and misunderstood along the way.

SI: The Great Depression has so far been lurking in the background of our conversation. But the 1930s crisis of capitalism features prominently in A Third Path. Austerity and authoritarianism are two running themes here, and not only for Brazil and Portugal, but also for the Soviet Union.

Elsewhere, you and some coauthors have written that austerity “presents itself as a confidence trick.” It’s a promise deferred: sacrifices today will contribute to the building of something greater tomorrow. What was corporatism’s “greater tomorrow” and how did that differ from other interwar-era confidence tricks?

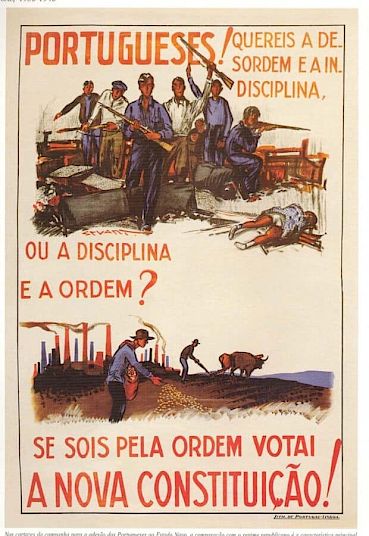

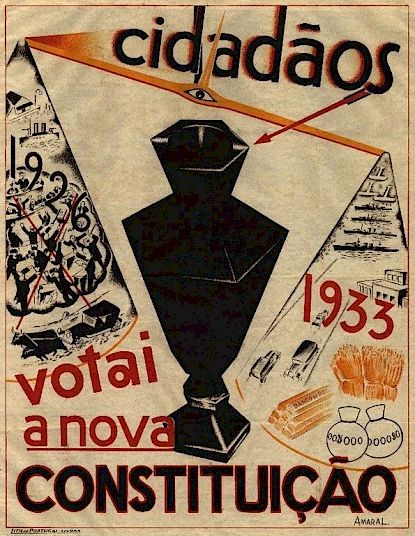

MT: The “greater tomorrow” of corporatism is captured in some of the posters circulating in Portugal ahead of the 1933 plebiscite to ratify a new Constitution, which formally established a corporatist political and economic system. Salazar in Portugal (much like Vargas in Brazil) promised order, stability, and modernization. Corporatists weren’t alone in blaming the so-called laissez-faire system for the inequities and social dislocation caused by the Great Depression, nor were they the only ones promising economic renewal. What sets corporatists apart, in my view, is that their programs weren’t just about accelerating industrial growth or revitalizing agriculture—they also advanced a moral vision of the economy.

Essential to the corporatist worldview is the emphasis on preserving existing social hierarchies through the vertical integration of social and economic groups into the state, alongside the promise of social peace between labor and capital. Corporatists emphasized economic justice, fairness in labor relations, and that individual interests should be subordinated to the greater good of the group or the nation. Both Salazar and Vargas defended their efforts to prioritize the economic well-being of the people, even if that meant curtailing certain political or civil liberties.

One way that I explore this line of moral-economic thinking in A Third Path is through state efforts to regulate fair prices in Brazil and Portugal, which became a cornerstone of corporatist policies aimed at social peace and economic justice. While price controls and fair competition policies were also used in places like the United States and Chile during this period, the justification for such measures differed from country to country since in each country, governments had to defend their policies according to local ideological traditions. In Brazil and Portugal, intellectuals, economists, jurists, and policymakers developed their own economic theories to offer a new definition of fair prices. Where classical economic theory treated prices as set by market conditions—shaped by supply and demand—Brazilian and Portuguese corporatists pointed to the unfolding economic crisis to argue that the self-adjusting market could not be trusted to efficiently allocate goods and resources. Instead, they argued that the price of essential goods should achieve harmony between the interests of producers, merchants, and consumers alike. Like wages, prices became variables that the state (alongside organized group interests) sought to regulate in the name of social peace and economic development.

By promoting this idea of fair prices, Salazar and Vargas attempted to brand their dictatorships a new form a democracy—one defined not by individual rights or political representation, but instead by economic justice. Yet those who designed this corporatist system developed a concept of justice grounded in order and hierarchy, rather than equality or accountability.

SI: Women were especially important to the corporatist price control system. Who were the “donas da casa” and what was their involvement?

MT: One of the more exciting surprises in researching corporatism was that special military tribunals were appointed for the task of enforcing price controls and other market regulations in both Brazil and Portugal. I argue that this institutional choice was no accident. During World War II, international supply chains became severely disrupted, leading to rising inflation and scarcity in essential goods in belligerent and non-belligerent countries alike—an economic crisis aggravated by the proliferation of contraband markets, price gouging, and speculation. The use of special military tribunals to adjudicate fair pricing epitomizes how interwar corporatist dictatorships seized on yet another economic crisis—intensifying their use of legal institutions both to dismantle prior protections and conventions and expand state intervention in the economy. Doing so, they put into everyday practice the notion that strong, centralized states might need to curtail free exchange and limit private property for the sake of national economic wellbeing. Price—or the promise of a fair price—offers a really interesting window for exploring how these authoritarian regimes tried to use and abuse law to consolidate their power, but also the unintended consequences of such efforts.

Beyond the political and ideological significance of these trial proceedings, I also use these trials to explore how retailers and consumers alike navigated the new laws and bureaucracies that now governed economic life. Certainly, these laws and tribunals did not really work to guarantee fair pricing for Brazilian or Portuguese citizens, but the promise of a fair price mobilized people to denounce their local retailers for profiting from the wartime disruptions and to demand that their government do more to stem the rising cost of living. For Brazil, I discuss how donas de casa (or “housewives”) were on the frontlines of efforts to enforce price controls and other market protections. The women were responsible for daily shopping and stretching household budgets, and so they were often the direct victims of price gouging. In major cities, some formed neighborhood groups to force local retailers into compliance with price tables and to gather denunciations against violators, initiating some of the economic trials taking place in those special tribunals. While these popular enforcement campaigns were quite limited in scope in the 1940s, they were nonetheless significant: even failed or incomplete experiments can generate new institutions that groups like the donas de casa can seize upon to articulate their own ideas of economic fairness—to define what they considered to be legitimate or illegitimate business practices—and to channel their grievances into petitions for the government to do something to address economic hardships.

In researching A Third Path, the kinds of sources I was working with didn’t permit me to explore the full extent to which popular classes were impacted by price controls or the many different ways that workers, consumers, and producers organized and protested against the government’s inability to deal with rising inflation. But the examples I did engage with inspired some of the questions I’m exploring in my current book project on the social and political history of inflation in postwar Brazil. Some preliminary work on this topic, including on the role of donas de casa in turning inflation into a target of protest and political mobilization, appears in my recent article, “Living with Inflation: Policymaking and Popular Practices in Search of Price Stability after Brazil’s Economic Miracle,” published in Radical History Review.

SI: At the end of the book, you show how, after World War II, the corporatist view of a “greater tomorrow” informed the emergence of Brazilian developmentalism. That chapter seems to be in dialog with Joseph Love’s classic work, Crafting the Third World: Theorizing Underdevelopment in Rumania and Brazil (1996). Was Love an influence on you?

MT: Joseph Love’s Crafting the Third World has been hugely influential in my evolution as a historian and in the development of this book specifically. For economic historians of modern Brazil, the promise and problem of “development” is such a rich field of debate not only because of Brazil’s impressive industrializing feats in the mid-twentieth century, but also because Brazil was home to some of the most important contributions to global economic thought: structuralism and dependency theory. Economists like Celso Furtado, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, and others developed these frameworks as homegrown responses to the development obstacles that Latin America faced. As historians like Love—and more recently Margarita Fajardo—have shown, these were serious, creative efforts to theorize how to generate economic growth and why certain developmentalist promises failed to deliver.

But in my view, the post-1945 focus on innovation and experimentation, while valuable, risks flattening the deeper and more complicated intellectual genealogies that underlie those theories. In particular, it can obscure the illiberal, authoritarian, and antidemocratic roots of some key strands of development thinking. Corporatism is one of those strands—not the only one, certainly—but one that I believe deserves closer scrutiny in the transition from interwar authoritarianism to postwar developmentalism.

I do this through a comparative lens—using the final chapter of the book to explore the complex afterlives of interwar corporatist experiments in both Brazil and Portugal. First, I begin with a historical puzzle: what happens to all the enthusiasm for corporatism after World War II? By 1945, corporatism was deeply compromised by its associations with dictatorship and fascism—despite the efforts of leaders like Vargas or Salazar to differentiate their regimes from those of Hitler or Mussolini. At the same time, corporatist economic policies had not fully delivered on their promises of social peace or economic stability. The war years brought disruption, inflation, and scarcity. So, I ask: what happens to a set of ideas that appears both morally discredited and practically ineffective?

The answer varies. In Brazil, the term “corporatism” is effectively erased—literally crossed out in drafts of legislation and constitutions—yet many of the institutions, policies, and frameworks created during the Vargas years persist. They are rebranded, adapted, or quietly folded into the new postwar democratic order. Not everything from the Vargas era was explicitly corporatist, but even those policies that were tied to that ideology often remained intact, albeit repurposed for a new ideological climate.

And while we can never know exactly what Brazil’s developmentalist state might have looked like without that corporatist precursor, we can see some enduring legacies: a strong role for the state in balancing organized interests; skepticism toward laissez-faire market solutions; a focus on increasing domestic production to support industrialization; the idea of just prices for producers and consumers alike; and a preference for technocratic over political approaches to policymaking. In this sense, developmentalism in Brazil builds on corporatist assumptions about the proper relationship between state, economy, and society—even as some postwar governments distanced themselves from the language of corporatism itself.

Portugal’s trajectory was quite different. Salazar remained in power, and the Estado Novo survived as Western Europe’s longest dictatorship until the 1974 Carnation Revolution. Yet even within that continuity, the postwar moment forced rethinking. Wartime scarcity and inflation had undermined confidence in corporatist economic management, prompting both critique and reform. Some in the regime argued that corporatism had failed; others insisted it had never been implemented fully enough. Still, rather than discard corporatism, the Portuguese regime sought to resynthesize it, blending its ideals with Keynesianism and other schools of economic planning.

In Portugal, corporatist organs remained the basic administrative and regulatory units of economic life. As such, they played a central role in achieving the goals set by the five-year development plans of the 1950s and 1960s. Portuguese economists and public officials adapted the corporatist idiom to align with the evolving ideological climate, presenting corporatist organs as intermediaries that could facilitate public-private cooperation. Catholic doctrine and the rhetoric of social peace remained central to official propaganda, even as bureaucrats increasingly embraced modern planning tools and quantitative methods for measuring development. While the Salazarist regime never abandoned its commitment to corporatism as a “third path” between two extremes, this idealism seemed out of place in a world increasingly dominated by Cold War polarizations. With the Portuguese example, we see how ideas can endure and even be reinvented, even as the world seems to be moving on.

Across both cases, what I try to show is that corporatism didn’t simply disappear after the war—it was reimagined. Sometimes this meant rebranding institutions, sometimes adapting ideologies, and sometimes building entirely new frameworks on top of old assumptions. Developmentalism, in both Brazil and Portugal, retained the corporatist belief in the state’s primary role in managing relations between labor and capital alongside a skepticism of the free-market mechanism and a preference for technocratic approaches to economic policymaking—even as it responded to new global paradigms and postwar realities.

SI: That’s an important intervention, and one that, no doubt, took a lot of research to make. Tell me about the experience of researching and writing this book.

MT: Writing and researching this book was, in many ways, a deeply immersive and intellectually rewarding process. One of the real privileges of working on a transnational history project is the opportunity it offers to travel and spend time in different countries. Immersing myself in different national contexts shaped the questions I explore in the book, as it meant grappling with distinct historiographic traditions and the intellectual stakes around corporatism in each country, and then working to bring those perspectives into conversation with one another. A Third Path originally began as my PhD dissertation, which I significantly expanded and revised over several years. Early in graduate school, I was fortunate to receive several fellowships that supported extended research stays in Brazil and Portugal—some lasting nearly a year—which allowed me not only to delve into local archives but also to engage in conversations with, and learn from, local scholars. I also made many shorter trips to revisit collections, follow new leads, and fill in gaps as the argument evolved. Of course, some plans didn’t materialize: I had hoped to trace certain intellectual networks into archives in Italy and France, but COVID-19 made that kind of travel impossible when it was most needed. So, like many researchers, I adapted and kept going.

One of the more challenging—but also most intellectually generative—aspects of the research was the need to take seriously the internal logic of repressive, illiberal regimes. I spent a great deal of time engaging with the worldview and institutional blueprints of those who genuinely believed that dictatorship was superior to democracy—not only in delivering rapid economic transformation, but also a fair and harmonious economic system. I pushed myself to look past the misleading promises and repeated failures of corporatism to grapple with why it held such appeal for so long and understand its legacies. That work was often difficult, but it yielded some of the book’s most important insights into why the study of corporatism still matters today. Even though the political and ideological projects I examine are relics of the interwar decades, they still raise enduring questions about the vulnerabilities of liberal democracy. By tracing the political, economic, and legal arguments that underpinned the rise of corporatism, I offer some powerful examples of how easily dictators can seize on moments of economic crisis and instability to erode individual rights and protections, dismantle governmental checks and balances, and consolidate power. Revisiting the Vargas and Salazar dictatorships, I think, helps us gain historically grounded insights into why and how certain anti-democratic visions gain traction—and what is at stake when they do.

SI: That is a good note to end on. Thanks, Melissa, for sharing your work with us. A Third Path will be of great interest to the Toynbee Prize Foundation’s reading community!

MT: Thanks so much, Sergio! It’s been a great conversation—I really appreciate this space to share a bit about the forgotten history of corporatism with your readers.

Sergio Infante is an Editor at Large for the Toynbee Prize Foundation and is a doctoral candidate in History at Yale University.

Melissa Teixeira is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania. Her work focuses on modern Brazil, with particular interests in legal history and the history of economic life.