Collaborators of the New Order—Fascists, Nationalists, Traitors, and Opportunists in occupied Western Europe: An Interview with David Alegre

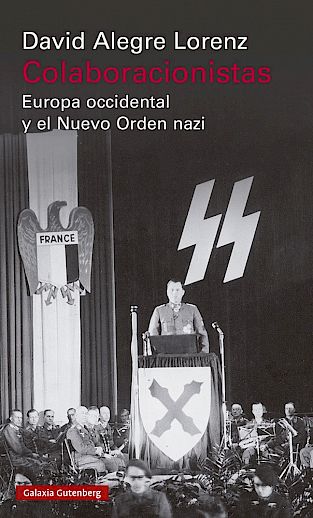

Empires are not ruled only by force. Some degree of resignation or collaboration from local populations is needed. Despite its brief lifespan, the Third Reich was no stranger to this logic. In Western Europe, tens of thousands of European citizens took part in Nazi imperial policies of domination and spoilation, spurred on by fear of losing an unrepeatable opportunity and inspired by the dazzling triumphs of Hitler’s Germany. Such Nazi collaborators are the main subject of David Alegre’s most recent book, Colaboracionistas. Europa Occidental y el Nuevo Orden Nazi (Galaxia Gutenberg, 2022). Born in Teruel, Spain in 1984, this researcher and lecturer at the Autonomous University of Barcelona delves into collaborators’ experiences, their mental universes, their political strategies, and their stormy relations with the German Nazis, including the creation of volunteer units for war against the Soviet Union. Far from seeing themselves as mere pawns, the collaborators believed that close and loyal cooperation with the occupiers would be the fastest and most effective way to promote their personal interests and political projects. Marginalized by their convictions as traitors and persecuted by the Resistance, they would end up signing a blood pact with the occupiers, contributing to the plunder of their countries, and pushing their communities to the brink of civil war.

—Salvador Lima, European University Institute

SALVADOR LIMA: Where does your interest in fascist collaborators arise from?

DAVID ALEGRE: As a history student, I had studied the violence of the Yugoslav War (1991-2001), so this was my primary research topic when I thought of doing a doctoral thesis. However, my mentor and friend Javier Rodrigo advised me to choose a more compelling subject, considering our Spanish-speaking academic and cultural environment. That led me to Spain in the context of the rise of fascism and the Second World War. I wrote my doctoral thesis on the fascist collaboration in Spain, France, and Wallonia, during the 1930s and the 1940s. I chose to study this from a transnational view to overcome Peninsular constraints, because I have always thought that history must address the great questions about human nature and its interactions within a specific community. In other words, history must be ambitious and deal with issues that consider the local, the national, and the global. Fascist collaborationism is just such a topic and it happened in context of extreme violence in Europe. It was a moment of rupture of social, cultural, and political balances wherever the German occupation occurred, or its allied movements rose to power. So, I was trying to understand how individuals and groups reacting to such traumatic experiences as invasion, purges, and the turmoil of war, could bring about different social and personal behaviours.

SL: The book deals with the situation of almost every Western European country during the Fascist Era before, during, and after the war. Yet, you chose not to study the Italian case. Why was that?

DA: Fascist Italy is extremely complex to address in a broader book like mine. In fact, there are already excellent academic works on Italian fascist experience and its collaboration. The works of historian Claudio Pavone have been essential to this matter, renewing the perspectives and the possibilities of Italian historiography. For instance, he questioned whether the violence in Italy between 1943 and 1945 constituted an actual civil war. It is a debate that relates directly to my research, given that one of the things I tried to unveil was to what extent, in each occupied country, the confrontations between the Resistance and the collaborators were proper civil wars. In any case, Italy deserves a distinct kind of research. Its position was very different to the rest of fascist Europe. It was the first birthplace of fascism, and it was not occupied, but rather an ally to Nazi Germany until 1943. In this year, multiple alternative powers insurged against the Italian state, there were several confrontations between partisans and fascists, and we also had the Allied landings. The same dynamics in the Republic of Saló are not easy to explain. In conclusion, it is a case study that diverges widely from the other national cases I included in a book, which is already complex and long enough. That said, Italy is a consistent presence in my book. Italian personalities and ideas had an evident impact on the occupied countries and in Spain itself.

SL: What were the challenges to including Spain, a neutral country traditionally seen as belonging to the margins of Europe, in the history of World War II?

DA: It has been one of the great struggles of Spanish academia to bring our country into the historiographic tradition on fascism and World War II. We need to eradicate that nonsense stereotype about Spain’s exceptionality in the first half of the 20th century. Spanish exceptionality begins in 1945: when fascist regimes crumbled in Europe, Francoist Spain remained alive for thirty more years. Spanish history at the time is Atlantic, European, and Mediterranean, so we cannot discard its fascist connections with the occupied countries and Germany. To understand the Fascist Era, we must fully contextualize Spain within the violence and political turmoil of the 1930s and 1940s, not just considering the Spanish Civil War, but also the transnational Resistance movement, the fascist inspiration of Falange, Franco’s stance before the war, and the Spanish military participation in the Eastern Front. The Civil War was a turning point in fascism’s evolution and its process of radicalization. Italy and Germany collaborated with the rebelling Army and the resulting military regime embraced, initially, some of the fascist tenets through Falange Española. On the other hand, World War II had a deep influence in the Spanish society. It was also a main issue for the political and solidarity networks of Spanish National-Catholicism and Falange’s cadres, and it gave the Army a possibility to fight against the Communist International.

SL: What struck me most of all in the book was its wide scope. You have considered so many national cases, the Scandinavian countries, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain. As a historian, what methodological and linguistic challenges did you face in conducting your research?

DA: This book was indeed a big challenge in and of itself. The final version was a result of many years of personal maturation as a historian. Since the defence of my doctoral thesis in 2017, I have gone through a lot of study and research periods abroad. I have published many articles and other books with extraordinary colleagues. So, considering the current hastiness within academia and pressure to advance through a series of milestones ever quicker, I believed it was a good thing to leave my thesis to rest for several years. It allowed me to grow professionally, to learn new languages, to acquire new intellectual tools, and to navigate different archives and libraries. This way, I could enhance my thesis, expand its scope, and construct a much more compelling argument and book. Scholars usually dismiss this point, but it is important to produce knowledge that could be compelling to the public. It is important to offer the general reader a complex explanation of the trajectories and personalities of our history in a way that is accessible and serious at the same time.

On the other hand, I am a strong advocate for this kind of circular and transnational history, one that observes the transfers, movements, and impact of peoples and ideas across borders, overcoming the national narratives of each country. I was very interested in understanding the circulation of fascist and right-wing ideas over different political spaces. How did I work with such diversity? I wanted to combine each specific experience with the transnational movement as a whole entity. This requires of the historian dynamism and ambition, jumping through and straddling scales and countries. It is in the local where we see the pure manifestation of the problematics and interactions of collaborators, regarding their national context and their relationships with Nazi officials as well as Himmler’s projects for occupied Europe. Understanding each organization of collaborationism is useful in addressing bigger questions about Nazi Germany and the scope of the war.

As to the linguistic challenges of the research, as a Spaniard, let’s say it required an iron discipline to learn Northern European languages. Learning German was not just important in order to gain access to German literature and sources; it also paved the way toward learning the structures of other Germanic languages, such as Dutch and Danish. Adding good dictionaries and all the current electronic resources, I was able to achieve the kind of linguistic diversity my research demanded. Further, in each foreign library I visited there was amazing staff that helped me find the materials I needed and guide me through them in many cases. The biggest challenge was not so much the foreign languages but knowing and understanding the national debates of each historiographical tradition. The scope of academic literature on fascism and World War II in every country is impossible to manage for one individual in one project. The best way to deal with this were book reviews. Good reviews allow you to acquire a general view of a certain book and to identify the chapters or the concepts you can extract from it, saving you a lot of time.

Learning German was not just important in order to gain access to German literature and sources; it also paved the way toward learning the structures of other Germanic languages, such as Dutch and Danish. Adding good dictionaries and all the current electronic resources, I was able to achieve the kind of linguistic diversity my research demanded. Further, in each foreign library I visited there was amazing staff that helped me find the materials I needed and guide me through them in many cases. The biggest challenge was not so much the foreign languages but knowing and understanding the national debates of each historiographical tradition...The best way to deal with this were book reviews. Good reviews allow you to acquire a general view on a certain book, to identify the chapters or the concepts you can extract from it, saving you a lot of time.

SL: It would be nice for our readers who have not yet read your book if you could explain who the collaborators were. What connections did they have between them and with Nazi Germany? How did they confront their specific national politics? You wrote that not all of them were necessarily convinced or hard-line fascists. What were their motivations then?

DA: Fascist or Nazi collaborators were part of a very heterogenous collective. There were many different profiles within it. Most important, we must understand that fascist parties or organizations that in 1939/1940 opted for collaboration with the occupiers suffered a strong drainage of their militants at that very moment. Why? The ideological core of these parties was a form of extreme right-wing nationalism, a trait that defines fascism as a political culture. Their projects were nationalist and in search of national greatness and expansion through violence. Therefore, most of these nationalist militants in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, and Scandinavia could not support their organizations any more since their leadership had chosen to aid an occupier power, even if they agreed with Nazi ideology in many aspects. Germany was an expansive empire that looked for continental hegemony and that had not hesitated in annexing countries or regions with population of Germanic origins. For instance, the National Socialist Movement of the Netherlands (NSB) and the Flemish National Union (VNV) had originally advocated for the union of the Dutch-speaking countries with the creation of the Great Netherlands. How could their members endorse a German occupation and give aid to the SS when Himmler had different plans for the Low Countries as a whole? These contradictions between the nationalist core of fascist parties and their political interest to participate in Hitler’s New Order were traduced in the draining I mentioned. What happened with the collaborationist organizations after 1940 then? The space left by the original members was taken by last-minute opportunists. These social climbers had no ideological attachment to the fascist cause. Looking for wealth, power and influence, many of them ended up by becoming extremely politicized, even to the point of volunteering to the Eastern Front. After all, at 1940, the Third Reich seemed marching to total victory, so many young men in the occupied countries saw the collaboration as a chance to participate in a glorious and winning campaing.

In any case, the draining of the old nationalists militants and the incorporation of new blood is a common logic in the political and military turmoil of the period I studied, between 1931 and 1951. Even in Spain, during the Civil War and after the consolidation of Franco’s regime, there was exchange of cadres in the National movement. The profascist militants of Falange did not agree with some of the violence methods praticed by the Army, nor with the fusion with the traditional national-catholic sectors, so they left the Movimiento. The Yugoslav Communist Party went through a similar process, multiplying its ranks ten times during the war at the expense of other socialist or democrat parties. The conclusion is that times of war and turmoil produce these opportunities to renew existing political organizations and, most important, to radicalize them. Radicalization is always a window to social climbing in political parties.

What I intended with this book was to find a proper definition of collaborationism. Collaboration could cover different attitudes and reactions. As a matter of fact, there were many ways, passive or active, of dealing with the occupation and not all of them were politically-aimed. If we do not consider these differentiations we would be accusing many individuals or groups, who were just trying to survive, of being collaborators—especially women. Many widows or single women of the occupied territories had no choice but to seek the protection of German officials, marrying them in some cases, in order to be safe from masculine violence and have a means of life. Is that collaboration? I think not. At least from a political point of view. It is survival.

If we do not consider these differentiations we would be accusing many individuals or groups, who were just trying to survive, of being collaborators—especially women. Many widows or single women of the occupied territories had no choice but to seek the protection of German officials, marrying them in some cases, in order to be safe from masculine violence and have a means of life. Is that collaboration? I think not. At least from a political point of view. It is survival.

SL: So, beyond the political interests of nationalist parties, you would say there were many grey areas and various different forms of collaboration.

DA: Indeed. There is also the question of economic collaboration, which is an entirely different issue to deal with as a historian. In France, for instance, big industries kept working under German occupation and with the Vichy regime. If some of them had fluctuations in their performance and productivity, it was due to the changing needs of the German war machine, not to forms of “economic resistance.” Later, during the épuration of 1944 and 1945, French industrialists justify their collaboration as a way to avoid being dismantled and relocated to Germany. Be that as it may, because of their political leverage and the needs of French reconstruction, these men did not suffer political and social purges as other professional and social groups.

In fact, the case of the French industrialists is a good example of the kind of collaborators the Nazis looked for. In occupied countries, German agencies preferred to work with traditional elites, instead that fascist parties. This seems contradictory, but it has its logic. Nazis were practical. Because of their social legitimacy, political stature, and economic resources, elites have much more credibility and could be reliable allies with the proper incentives. On the other hand, local fascist parties were seen as marginal and discredited gangster organizations. This is why they meet the systematic disregard of Himmler and other Nazi officials. Nazi priorities were different and changing; they were not even the same for every country. Besides, German policy in occupied lands was not a perfect system. Each Nazi agency had its own officials, views, and ambitions and they tended to compete for power and money. The relationship between the Wehrmacht and the Waffen SS was not harmonic. This brought different opportunities for clever collaborators, but also made the collaboration itself a very difficult endeavour, given the changing trends and corruption of German authorities. As a result, there was an environment of mistrust and competition among collaborators, who had no chance but to escalate their fascist attitudes if they wanted to be respected by the occupiers. They knew that, once they got into the game with the Germans, there was no coming back to the national fold—there was only Nazi victory.

SL: You have explained why Nazi agencies sought the collaboration of traditional elites. But what was their attitude towards occupation? What did fascism mean to them?

DA: For traditional elites, collaborating with the Nazi Germans was a way of guaranteeing the continuity of their nations, avoiding full annexation, and strengthening their mechanisms of economic and social control. This is a very important point that I cannot stress enough. What the collaboration of economic elites and right-wing parties demonstrates is the real extent to which fascism was built on traditional counter-revolutionary groups. They may have not shared all of the methods and violent ideas of Nazis and fascists, but on the whole, they did share the same furious anti-communism and reactionary views on society and democratic politics. The same process could be found in the National Socialist Party. If it had been a marginal organization until the early 1930s, it became the main political force in Germany when economic elites realized it offered an alternative and non-democratic way to gain power. There was, therefore, a fusion between Nazis and traditional elites. This observation is crucial to Spain, where the classic debate on the fascist nature of Franco’s Regime is not over. Now, if the building of a fascist regime depended heavily on the aggregation of traditional elites and counter-revolutionary parties, then it is completely legitimate to say that the Francoist State was a part of the fascist family. These are the advantages of working with a comparative perspective.

SL: However, collaboration in Western European countries was not just about national elites and local fascists. There is a shadow looming over this history and that is the Eastern Front. What was the ideological and meaning of the German-Soviet War for Western right-wing nationalists?

DA: In 1941, the fascist camp did not doubt that the German victory over Russia would be swift and glorious. So, thousands of European collaborators hastened to enlist in the volunteer units of the Waffen SS. It was the opportunity to demonstrate their commitment to the German cause and to gain renewed political leverage in their own countries as well as with Nazi agencies. Not to mention the expectations of adventure and glory that the Anti-bolshevist crusade inspired in all these fascist and ultranationalist groups. Alongside these idealists, there was also the classic elements to every volunteer military force: mercenaries, unemployed or unsatisfied workers, fugitives from justice, and other marginal men. On the other hand, the Waffen SS needed more soldiers. So, the enlistment and instruction process of the volunteers to the German-Soviet War was too quick and poorly prepared. As a rule, German cadres underestimated Soviet military force and thought the SS volunteers would have the opportunity to become seasoned soldiers during the campaign. Now, when the German army advance stopped and the big losses started to follow, the Waffen SS expanded and accelerated even further its recruitment campaign in Central and Western Europe, reducing the physical, ideological, or racial requisites and the time of instruction. The effect was a larger mobilisation, a poorer military force, and thousands of deaths and injuries in the battlefield.

In retrospect, the German-Soviet War is critical to understanding the ultimate development of the extreme right ideology. The experience of Western European volunteers in the Eastern Front is the great narrative and foundational myth of neofascist and far-right parties. The war against the Soviet Union was an argument wielded by extreme right-wing groups, during the Cold War, to legitimate their rightful place in the Western anti-communist alliance. The Spanish participation in the Blue Division is the paradigmatic example. In the 1950s, when the last Spanish POWs were set free by the Soviet Union, Francoist propaganda about the Blue Division became more present than ever in Spanish public opinion and popular culture. For Franco’s Regime, emphasizing the battle on the Eastern Front was a way of pointing out that Spain had already fought against the Soviets, that it had been in the European vanguard in the struggle against the Asian communist invasion, and so was a legitimate member of the Western cultural bloc and the Atlantic powers. In the rest of the Western European democracies, right-wing parties staffed by former fascists and veterans of the Eastern Front used the same narrative to underline their legitimacy as political actors.

As a matter of fact, veteran’s associations of the Waffen SS and the Wehrmacht played a very relevant role in this retelling of the war. The men of these organizations sought to restore their place in history and in postwar society, particularly by underlining their noble and humanitarian motivations, such as the recovery of bodies in Russian territory, the research on disappeared soldiers, and their efforts to support the politics of memory. Moreover, the veterans wrote a lot. Among them, Felix Steiner, a former commander of the Waffen SS, was the most prominent apologist of the war in the East. Steiner wrote a series of essays in which he vindicated the Waffen SS as the first Western international army, a predecessor of NATO in the struggle against communism. Moreover, they claimed that their resistance of the Soviet counterattack allowed the Allies to reach Germany on time, before the Red Army had occupied the entire Central Europe. From a purely objective and military point of view, they were not wrong. The thing is that they escalated this discourse, declaring that their fightsaved the West from a communist occupation. In their twisted view, this encompassed the representation of a European fraternity of peoples with Christian values against international Bolshevism. Vindicating the German invasion of the USSR was the loophole that former collaborators found to re-establish themselves as members of the European family. Amazingly, these fascist apologists and veterans turned a defeat into a victory, which would become a model for generations of right-wing sympathizers in Europe.

SL: Now, in the immediate aftermath of the German retreat in the East, volunteers of the Waffen SS came back to their countries to reclaim their place in the collaborator regimes. However, the war’s evolution had changed by 1944. Germany was being pushed out of the East and the Allies were already fighting in Italy, whilst rumours of subsequent landings in Northern France were widespread. Therefore, the collaborators had to fight against more emboldened movements of Resistance. Why do you hold that the concept of civil war could be useful and at the same time misleading to understand this domestic conflict?

DA: To speak about a civil war there must be a series of conditions that did not exist in the occupied countries. A civil war implies a dispute about the sovereignty of the nation and the legitimacy of the state between two parties that are equally qualified to exercise the government and rally the population, and that are equipped with similar military capabilities. Leaving aside Italy, where a true civil war took place in 1943-1945, these conditions are difficult to find in the rest of occupied Western Europe. What we find in those countries are movements of Resistance, that practiced forms of guerrilla warfare against collaborators. The scale of the fight is another relevant dimension to civil wars. The conflict between Resistance and collaborators involved minor groups. Both parties were staffed by very politicized cadres and militants, but their numbers were tiny within the national population. There were no general mobilizations, which usually occur in the context of civil wars, nor use of heavy arms and sustained firepower. Moreover, at any moment the Resistance was capable of seriously damaging the German Army and its command of the territory. In fact, most of the Resistance’s violent attacks were not directed at Germans. Against Germany, they may have used propaganda, but actual violent hostilities were against collaborators. Why? Because their fight was domestic. The Resistance knew they were fighting for the future organization of the nation. Therefore, the struggle was not about the continental war, but about terminating local fascism and the ultraconservative right. In any case, the concept of civil war may not be appropriate to describe the Resistance’s struggle, but at least it forces us to consider such domestic conflicts with greater nuance. That’s why the concept is useful and posing the question is attractive to historians.

SL: Near the book’s ending, you explain how the collaboration, the Resistance, and the eventual purges influenced the organization and the political cultures of post-war Europe. Do you think they are still important today?

DA: I’d say that they are no longer important. Many decades have passed, and the old generation of the war is gone. World War II and the fascist experience are almost prehistory. The truth is that the post-war myth around the Resistance and the anti-fascist struggle have come into questioning during the last decades. For many years, the résistencialisme, that is, the general idea that everyone opposed Nazi occupation by joining the Resistance or the Allied Forces, was very popular and fully integrated into the national narratives. It was a way of dealing with the past and restoring national self-esteem. After all, what the Nazi occupation and collaboration had revealed was the weakness of national unity. Collaborators demonstrated that the nation is not a natural essence that guarantees harmonic social cohesion. They fractured the popular belief in the nation. That’s the reason for the purges of political collaborators and the necessity to rebuild the social tissue with the myth surrounding the Resistance movement and partisan guerrilla. However, since the cultural revolution of 1968, the new generation of Baby Boomers has challenged these views of their parents and leaders. Many students and workers started to see post-war order as a fraud that had not changed the essential vices of the system. The result was the end of the résistencialiste myth and the revisiting of the fascist experience through different perspectives. After all, whether we like it or not, fascism is part of European history. The new generation of historians realized they could not keep hiding it in their national histories. This meant a necessary renewal of lines of thought and studies of fascism, the war, and the dépuration. European societies have dramatically changed since then, so they have accumulated new problems. Right and left have also adapted to the new era, reshaping their programs and discourses to modern issues. Nobody remembers anymore what is to be under a fascist regime. Therefore, post-war antifascist consensus has weakened, and the current wearing of the Welfare State and its economic model produces the expansion of the extreme right constituency as a ‘punishment vote.’ That’s why studying the history of collaboration and the myth of the Eastern Front is crucial to understanding the true colours of far-right parties.