Dancing in the Battle for the Mantle of the Politically “Modern”: An Interview with Victoria Philips

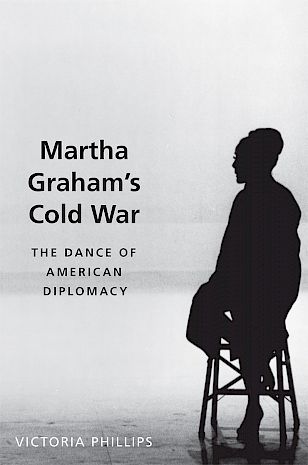

“It is that we continue to live as if this were the 20th century, even though we have formally moved to the 21st century,” lamented the former Bolshoi prima Ballerina Olga Smirnova as she announced her decision to defect to the Netherlands. I had just finished reading Victoria Philips’s monograph Martha Graham’s Cold War: The Dance of American Diplomacy (Oxford University Press, 2020) when I read Smirnova’s statement. In her innovative monograph, Philips places Smirnova’s decision in a longer history of moments where “[c]ulture met political aims, as private met public needs, and apolitical ideology served politics” (p. 2). Smirnova’s statement rests on the fact that her cri de paix situates itself above the political quagmire, in the higher realm of the arts—for the artist, as Philips notes, derives “deep political import” from her “claim to be apolitical” (p. 223).

Philips provides us in this recent book with an innovative and relevant example of this “politics of antipolitics”: the life and works of Martha Graham. Through a carefully knitted narrative that spans decades of touring, Philips provides us with a detailed account of the role that the “Highest Priestess of Modern Dance in America” played during the Cold War. Drawing from archival sources all around the world, Philips captures the paradoxes, tensions, and contradictions that surrounded Graham’s involvement in a series of dance tours around the world in which she served as an emissary of Unitedstatesean soft power, in the midst of a international struggle for the mantle of political modernity. Indeed, just like Smirnova, Graham’s project was deeply anchored in a modernist understanding of time. But as Philips shows, the promise of modernity was full of ambiguities and ambivalence. Graham’s modernist dance was, at the same time, sacral and secular. It embraced womanhood but shunned organized female emancipation, or feminism. More dramatically, it elevated individualism but depended on the support of the state. Aesthetically, it claimed to represent abstract universal experiences but also purported to capture the particularity of Unitedstatesean (and even non-Western) cultural forms. As we saw above, it was politically antipolitical—and the list goes on.

In our days, as Smirnova reminds us, the battle over the plural meanings of the “modern” is far from over. Perhaps, in that sense, we are all still living as if this were the 20th century. In our conversation, we explore what Professor Phillip’s book reveals about the ghosts of the Cold War and their claims to modernity that still haunt our political and aesthetical imaginaries.

—Daniel R. Quiroga-Villamarín

DANIEL RICARDO QUIROGA-VILLAMARÍN: Please tell us more about how you came to this project. In the introduction and later in the acknowledgments you mention that you were trained as a dancer yourself, and that you even worked with Martha Graham in the 60s and 70s. You also note how there was a disconnect between your life as a dancer and your personal and political life. Could you tell us more about how these lives came together and if they later collided with your life as a scholar?

VICTORIA PHILIPS: When I was very young, I was bitten by the dance bug. Oddly, I was very, very chubby as a small child, fat, really, and was not promoted along with the other slim, Gazelle-like girls in ballet and modern dance. So, my mother, who is renowned medieval historian,[i] decided that I should take 17th and 18th-century French courtroom dance classes, which I did. I learned the notation from the court of Louis XIV and became one of a handful of people in the United States who could do a proper minuet. And so, I performed professionally starting at the age of 10—at Lincoln Center, in various films, at universities, etc. I was bitten by the performance bug, and started doing some theater, then industrial films, print catalogue modeling. I auditioned for the soap operas, as we all did! And then, I saw Martha Graham in performance. Not Graham herself, of course, but the company. This must have been about 1976. And I looked at it and I said, “I want to do that.”[ii] And it was this moment of absolute “that.” It's apparently something that many Graham dancers feel when they when they see the Graham technique for the first time. But I know that when I have that same sense, when I'm studying something, or when I'm in an archive —it's that “ah-ha” moment that takes you to someplace where you wouldn't have normally gone had you not been there in that moment. That's how I found Graham.

I went to a very liberal, socialist high school that encouraged us to follow big ideas and allowed me to pursue a performing career. So, I started going to the Graham school every morning and taking independent studies in academic topics in the afternoons. By the time I was 18, to my parents’ great chagrin, I announced that I would not be going to college. They both had advanced degrees from Harvard University, and they have their eldest daughter saying that she would not even be pursuing an undergraduate degree, anywhere. This was not met with leaps of joy. They asked for the keys to their apartment. I was on my own. And I became a waitress, emergency telephone answering service operator, dressed in a cardboard house, and handed out leaflets for real estate brokers on corners in the West Village—that kind of thing. Doing side jobs, I continued to work and study with Graham, with Martha herself some days, performing in small companies. I learned the repertory for the corps.[iii] I was also trained by a man named Bertram Ross who had been her partner (and who appears in the book). They had a falling out, but I didn't know it at the time. Bertram was an excellent teacher. At night, I experienced New York and the club scene, and woke up a few hours later to take Pilates (it was only dancers!) and ballet barre as a warm-up for company class with Graham. So, when I was writing about Studio 54 and Manhattan in the 1970s in the Graham book, I kind of knew what people were talking about when I quoted them. I was very much there. But no one would have known me.

I was at the school when the company left on the “Jimmy Carter goodwill tour” as a follow-up to the Camp David Accords (see chapter 8, pp. 239-264). I had no idea what was going on in the Middle East or Israel. I knew something about the Temple of Dendur being re-built inside the Metropolitan Museum. But all I really knew was that there were fewer people in class, that the company was gone.

So, despite my educational background, I had zero identification with politics, which is surprising because at the Walden School—where I went from pre-school through high school over 1963-1978—we were socialists, Upper Westside communists. We were very progressive. History class for us was going to Vietnam peace marches. We had two graduates who were murdered, as they were trying to sign up voters in the South. The students organized to expel the school’s drug dealers who were students. Not the administration. It was a politically charged atmosphere. I very much saw a division between my work doing Louis XIV minuets and what was going on with Civil Rights, the Equal Rights Amendment, Vietnam, Nixon’s Watergate. And again, this is surprising because we were actually put in feminist classes at the National Organization of Women in NYC (NOW); we read Our Bodies Ourselves. But that was always very separate from what I did as a dancer.

I had no interest in history. I loved English and the Greek myths. Eventually I left dance, defeated, by my twentieth birthday. It was like a funeral for me, that birthday. I hadn't made it. I went to a division of Columbia University for older students and decided to study English literature, Greek myths, creative writing, and took one history course —just one! I did quite poorly, too. We were a motley, determined lot: a child actor who was no longer cute, the number-seventeenth ranked tennis player in the world who didn’t want to teach tennis, a woman who had been airlifted in from Cuba during operation “Pedro Pan,” a man who had made millions in construction. We all wanted something different. And I wanted nothing to do with Martha Graham, nothing to do with dance.

After college, I had a career on Wall Street. I thought I could write fiction at night. I published a few small pieces and started an MFA in fiction at NYU. Then, I retired to raise children. I still have a novel in the drawer. I was always interested in the arts. My daughters’ school needed an arts curriculum, no one knew anything about the arts or dance history, and they needed somebody to teach. And I said, well, I'll teach! But all I knew was Louis XIV and Martha Graham and I had no idea what came between the two of them. And so, I took the subway back up to Barnard College, and took a class in dance history.

I took the class with Lynn Garafola. When I read her work, I was completely taken with history—the history of dance and cultural history. I kept taking classes and got my MA degree with Lynn and Tom Bender, who did transnational history at New York University. I was then admitted to Columbia University under Eric Foner and Lynn. I applied to do politics and dance because I had become very interested in the way dance technique in the interwar period was used to express political ideas, going back to my roots. This was one of the heydays of Columbia. I worked with Alan Brinkley, Carol Gluck, Anders Stephenson, Alice Kessler Harris, Mark Mazower, of course, Eric Foner, Ira Katznelson, Ken Jackson—I'm sure I've left somebody out. But as you see, the list of these great geniuses just went on and on, some of whom were at the end of their careers. So, they were really concentrating on us as students, not establishing themselves. They were generous and rigorous.

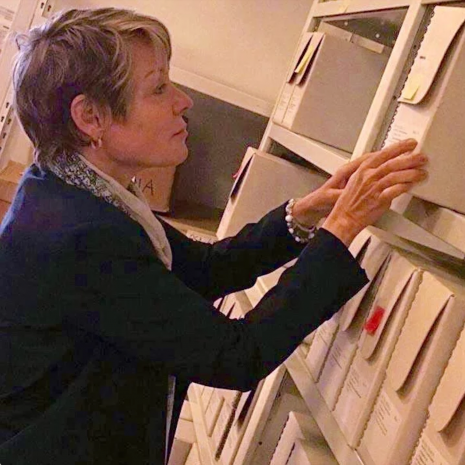

Then, the Martha Graham archives opened. At first, I didn't want anything to do with that or her, but I had gotten to know the archivist at the Library of Congress. I had gone to the Library of Congress to look at some dance records and I wrote her a thank you note. And she wrote me back and said, “no one has ever written me a thank you note before, and by the way, I've just opened the Martha Graham files. They've been closed to researchers until now, would you like to be the first person in?” Well, who could turn that down? So, I got on a train thinking “wow,” but I was also concerned because it was just getting in the way of my real work.

The first thing I did was to delve into Graham’s scrapbooks, and there was the Nazi insignia and a letter from Joseph Goebbels, inviting her to perform in a summer festival just before the 1936 Olympics in Berlin. The files also had her reply, which was astonishing. She had taken many Jewish dancers into the company during the interwar period when there was a lot of anti-Semitism in the United States. It was an astonishing letter. I thought, okay, that's political. She is taking a stand. But nothing US government-related. I knew from being in the studio that she was very pro-civil rights; she took African Americans into her company in the in the early 50s. She stopped touring the South at the same time. She had taken Yuriko—who just passed away at a hundred and two years old—out of an internment camp after Yuriko was released (I’m pretty sure due to the influence of Eleanor Roosevelt). And she toured with Yuriko during WWII in America. So, she was really forward thinking when it came to racial justice. So it wasn't so surprising that she would take a stand in 1936.

But I had remembered her saying: “My work is not political” in this grand kind of Hollywoodesque deep voice that she had. Very retro. I could hear her when I read the archive. And so, as I was leafing through the scrapbooks, there's a letter from George F. Kennan, author of the containment strategy. Then there was a letter from Eleanor Dulles. “Dulles” I thought, “that name sounds familiar.” After a little research, I saw that she was the sister of the Secretary of State, Foster, under Eisenhower. And I wondered, what is she doing talking to her? I also found invitations to meetings in Washington to discuss the problem of Soviet influence in Asia after she had toured Asia in 1956. Meetings with Truman. And I thought, this is very strange! And all of a sudden, I put together that this this was a very political story. Somehow, she was attached to the US government. This piqued my interest. And that started the whole thing.

I had already completed my master's thesis on Moscow's influence on American modern dance during the interwar period. I had found things in the in the Soviet archives, especially from Department for Agitation and Propaganda. They had material on the directing of theatre in the US, the topics and approach, which then got translated into dance productions. Works like “Hunger” during the Depression. I even found dancers who had been in the Communist Party who were alive and willing to talk about it. One had danced before 1932. It was a great project. And American Communist History wanted to publish it.[iv] I was very lucky —I worked with a man named Dan Leab who was another generous scholar. And then the French wanted to make it into an exhibit. But no one in the United States would have it because they didn't want me to say that Americans had been communists. Or that American modern dance technique had been deeply influenced by communist people and socialist thought. And it got really tricky, because I refused. I would not reframe them as “fellow travelers” or “left-leaning” if they were card-carrying communists who believed in Marxism, studied it, and embodied it in dance. It made me truly understand that McCarthyism lives. The Library of Congress acquired a huge collection on The New Dance Group, with communist roots. So oddly, the US government under Bush II sponsored the exhibit, Politics and the Dancing Body, that recognized the importance of the communist movement in the development of American modernism in the arts.[v]

Through my research, I came to understand that she had toured under every single Presidential Administration—from Eisenhower to George HW Bush. We had no clue — she had obscured it, as had government records! Because she was posing as apolitical for the government. Many of the State Department files related to Martha Graham were siphoned off and put in Arkansas with the Fulbright collection. So as part of cultural diplomacy, some tour documents were relegated to Arkansas. So, when you went to the government national archives and looked for Martha Graham, it seemed as though there were two tours, maybe a third under Kennedy hinted at. But because the papers from the other Presidents weren't peeled off and put into that Arkansas archive, the natural assumption would have been that those tours didn't happen. But then starting with oral histories with Graham’s living dancers, I could trace the whole thing through international archives.

DRQV: How do you situate your work in the broader waves of scholarship that are recasting our understanding of the Cold War. Traditionally, the US and the Soviet Union were juxtaposed as intrinsic opposites—as you call it, a “traditional bipolar view” (p. 30). In this sense, I enjoyed that your monograph shows many points of cross-fertilization between these two Great Powers, in dance, politics, and beyond. For instance, I was drawn to your claim that the dispute between the Soviets and the Unitedstateseans was acerbic not because of their differences but rather because they both claimed to be the true inheritors of a shared ideological horizon: that of modernization. Indeed, as you show, “[p]ropaganda surrounding these issues became vital because foundational tenets were shared by” both camps (p. 21). Before we jump to Graham, could you tell us more about the shared understandings of the modern—in dance and beyond—in the US and the USSR (and even Germany or Japan) in the interwar period? I am particularly thinking of Isadora Duncan’s embrace by Lenin (and of the controversial figure of Mary Wigman).

VP: There is in the historiography of dance a long debate on who is the “mother” of modern dance. Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham have been named the mothers of modernist dance. So, you have these mothers wandering around, but they're all American, and I argue that that was a Cold War phenomenon—the victor’s history! Isadora Duncan was posited as the American mother of modern dance because she wrote a piece that appeared in the newspapers called “I See America Dancing,” after Walt Whitman. No one questioned this; she was an American pioneer, and she talked about her grandmother on the Wild West. She seemed to be very into Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis.”

What nobody really had put together in a big way was the fact that the reason Isadora Duncan wrote that was because she had been previously been entrenched in the Soviet Union and Germany. She had married a communist poet in the Soviet Union, pledged her faith to Soviet communism by declaring “I am Red,” and she was trying to get back to America. This was the time in which there were various Red Scares. For Leninists, the idea was that she was barefoot; she was close to the ground; she had thrown off the Czarist tutu; her body could move. It was powerful, in a feminist way. Even if the movements themselves weren't particularly powerful in some of the lighter works, she made very politically dense works that are not shown much in the United States.

But this was not talked about when she was declared the ‘mother of modern dance.’ Modern meant free and democratic and thus, American. Yet Isadora Duncan had left a legacy in the Soviet Union. And there were still company members and children who had trained with her there at the start of the Cold War. George Kennan in his memoir’s chapter on writing the Long Telegram on containment, wrote about having seen Isadora Duncan dancers, but outside of Moscow. George Kennan, as a diplomat, was very aware of the battle of the modern between the Soviets and the Americans even in dance. He knew quite well that the Isadora Duncan dancers were not very good anymore. The “Isadorables” were terrible and at that point what the Soviets really had was ballet. They were the preeminent performers of ballet technique, Kennan noted.

In theoretical terms, what always fascinated me was this idea of modernization. Both the United States and the Soviet Union had this common endpoint of a better modern life. And then the question was, how do you get there? We can almost see an incredible simplification of this question taking place in dance. On the one hand, you have the Soviet Union with their traditional European ballet technique, where they are gorgeous when the group of dancers work together—the corps de ballet. They have stars, yet they are just more perfect than the others. By design, they all look the same in terms of the ideal: arched feet, just so tall, head a particular size, neck and limb lengths, turnout at 180 degrees. On the other, in the American modern dance everything is about the power of the individual, in theory. So, Martha Graham has her own technique. Doris Humphrey has her own technique based on her body. Agnes de Mille has yet another approach to dance, although it wasn't named for her. José Limón was vital to the government project in Latin America and the USSR. They had their techniques and they had companies named after them: Martha Graham, José Limón.

Before the Americans became dominant, during the interwar, while Isadora was doing her work, the Germans were innovating with a modernist dance. In the US, modernism in dance was only performed in large venues when the Germans performed. In 1936, when Graham was invited to perform at the at the Nazi Olympic Festival, Rudolf von Laban, who had been a founder of modern dance in my estimation, signed the letter with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. Labanotation, the notation system for modern dance, is still used today, named for Laban. So, there was this distinct connection between the German modern dance and the Nazi regime for a while—yet it became very strange and strained. Be that as it may, take Mary Wigman. She was unafraid to be an individual, to be ugly, to be heavy, and to be percussive. The idea was that you stripped down to the bare essentials to give way to the human—something so essential that we're that we're all going to understand what I'm talking about. Mary Wigman had a technique, school, and training system.

And what to me was completely fascinating was that this Wigman system came to the United States during the interwar and that's what founded the political leftist and communist dance in the United States, which, obviously, the Nazis wouldn't have been too pleased about. And with the rise of the Nazi regime, the Jewish Wigman dancers went from Germany to Israel, and founded a leftist modern dance school there. But obviously, the political ideology (the Aryan beliefs) didn't go with the dance technique to the US or to Israel. It wasn’t implicit. But this idea of the power of the individual, self-expression, of a stripped-down movement, a modernism that would offer something to all human beings in a better greater world that happens in the future, that remained in the modern dance. All of those things were right there, in those lines. The communists also used the Wigman technique to train.

At the same time, Martha Graham was doing what Edward Said would later call Orientalism. She was trained by Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn. They did these very kind of Orientalist works at the Denishawn School. I had some Japanese and Chinese students who looked at some pictures of them and they all fell into fits of laughter when they saw these pictures. It was this mélange of India, Japan, and China, because this was in the 1920s and there was this Egyptomania gripping the nation. And this was what Graham was doing with them, and even later once she split from them. And it was hot. It was vaudeville. They could sell it; they could perform it. But there was nothing “stripped down” or “modern” about this.

In Graham's early works, she was standing there in gold headdresses and flowing fabrics. She had a few protest works, such as Heretic, but it was not until 1930 that Graham had a breakthrough with her work called Lamentation, which she performs in a cloth tube.[vi] I think she got the modernist message, really, by looking at the Germans, because her lover was German and the Germans rehearsed at her studio. They were reading Nietzsche; they were discussing Kandinsky. Graham and her lover were going to Museum of Modern Art and were digging into this idea of abstraction. That was the impulse for Lamentation.

On that basis, her technique emerged. Unlike the Wigman technique, Graham built her technique on breath. So, inhale and exhale, and what happens to the body after a particularly a hard exhale—crying, laughter, and sexual moments. The idea is that the contraction—one that would be accompanied by a shout out (or a cry from pain)—showed the audience an unmistakable human action that everyone would understand. She did all sorts of things with gestures that would, in theory, translate to anyone, because they are almost animalistic. When I was studying with her, she used to tell us to go to the zoo and watch animals. That that's how we would learn to move innately, by instinct. You had to pick it up in terms of the way the human body moved, as an animal breed.

But then Graham’s next move is that she says: “I am not European.” She's very American, this way. There was a Japanese dancer Michio Itō, who had trained with Wigman and then came to New York. He was a leader in New York, and Graham danced with him. Then of course, he went back to Japan, with WWII. Graham got extraordinarily nationalistic before the US entered the war. She said, “we don't want the German art, we don't want the Oriental influence.” She had this urge to make an American art. She had been steeped in Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis” and embraced Manifest Destiny. In her own self-stylization, she even implied that she grew up on the frontier. Of course, she did go to California when she was a teenager, but all of this mythic crossing as a child was mostly that. Yet this essence went into her work, certainly by 1935 with her work Frontier, but also in Primitive Mysteries in the early 30s.[vii] So, there was this dual impulse. One was the pure modernist, abstract; and the other was to make something deeply American.

Once the Cold War begins, that's almost exactly what the doctor ordered: deeply American, but with global traces. Melting pot stuff. So, Graham certainly wasn't framing herself in order to get work with the State Department or to be recognized by government. It was just a great, timely match. However, very early on, she was recognized by Eleanor Roosevelt and was asked to perform Frontier at the White House. She became the first modern dancer to perform there in 1937.

Ideologically, she always believed in democracy and freedom. That's where her support for the Spanish Civil War came in, with the fundraisers in New York for medical aid and the Lincoln Brigade. At the fundraisers that supported a duly elected communist government, Graham performed Frontier! She always believed in democratically elected governments. But this area of her life is fascinating from a Cold War research perspective because her FBI file largely starts in the 1970s (the previous decades were erased). I've ordered it multiple times, under every imaginable name she's ever had (she was married, although she was known as Miss Graham, she was married for a while). I've tried everything. For the FBI, her life starts in 1974. And at the National Security Archive, thanks to Tom Blanton, I discovered that, many, many, many years ago someone ordered her FBI file and got a file that noted that the FBI was reporting on her involvement with the Spanish Civil War relief effort (medical funding for relief) in the 1930s. That has been purged from our governments record if you order it today from the FBI, but they still have it at the National Security Archive. It was the lack of information and the difficulty finding sources (and her denials) that made me understand how deeply political this actually was.

DRQV: We will jump to your sources in a second. But before that, I wanted to pause again in this tension. Modern dance, like the other radical left and right avant-garde arts in general, seems to sprout first in the poisonous climates of central Europe after the ravages of the great war. In different ways, Dadaist, Expressionist, and Cubist projects across the board attempted to synthetize a highly abstracted sublimation of the human experience—from Wigman’s Hexentanz to Kandinsky’s paintings (which Graham admitted she wanted to emulate to a degree (p. 39-40)). But it seems to me that these central European vanguards also felt the urge to portray the specific suffering of their historical context and peoples, creating a variety of traditions that oscillated from folk revival to socialist realism. Modernist art, in other words, developed in the interstices of these two powerful pulls. Could you tell us more about how Martha Graham navigated these tensions between universal abstraction and the particularities of local culture? Especially as she moves around the globe, retelling classic myths to Greek audiences, reinventing the Old Testament for an Israeli public, and so on. I am asking this because your monograph offers, above all, a rich history of movements. I refer to both the movements of the dancers at the stage, but also of the company across the globe.

VP: Martha Graham denied being “modern” because she had a deep understanding of having to be of her time and of her moment to stay relevant. One of her great quotes was: “I'm a thief, but I only steal from the best.” Then she named Picasso and others. And she was—she was a thief! But she put it all together in her own way, and she borrowed from all over, which included current cultural references, like Frederick Jackson Turner and later orientalism with the story of Cleopatra that opened in the Temple of Dendur during the 1970s Egyptomania in New York.

She took that story and performed it in Egypt on behalf of Jimmy Carter. But there was, if you go back to the cultural history of New York at that moment in time, the revival of Egyptomania. There was the building of the Temple of Dendur, encased in glass after being rescued from the “Soviet-created” flood. And it was the first time in the history of museums that they would sell timed tickets (to the King Tut exhibit). There had never been million-people exhibits before—this was unheard of. It was the first time that a grand public would be this interested. So, she was really working in that moment. Then to shore up the Camp David Accords, the Carter administration sent her to Israel and Egypt with a glittery Halston-clad Cleopatra that had premiered in the Temple of Dendur at the opening of its new home…in New York City! And that's what led her to say, “I am not modern.” Because she understood that modern dance was going to become a closed-end genre. And her idea of modern, was that something that could not become codified into a discipline (which of course, was not possible). She had to be current. In that she was kind of a perfect avatar of modernization policy, because she had a technique, she had a way of communicating a vision of highly productive, highly skilled, freed, new world. Yet, it was also very Western, and it was prescriptive: it said, “this was how you do it.” Ironically, that’s the opposite of freedom.

So, unlike the ballet, let's say particularly the Soviet ballet, where they're measuring your grandmother's arms and the size of her head and seeing if her feet flexed a certain way and made a certain arc before you were before you were taken into the schools (and eventually, stripped of individuality), Graham would say, “I can train anyone to be a dancer.” Literally, she said she could take any body. That's where the “modern” became performative. For example, take the character of Clytemnestra. It was played by Graham; by Pearl Lang (who was Jewish and married to a communist). It was played by a Mary Hinkson (an African American), and it was played by Yuriko—a Japanese woman. She was performing this idea that Clytemnestra, in essence, lives in all women of all body types. You don't have to have the body type; you have to have the soul! Work on your dance technique and then you can be Clytemnestra, because we all are. Now the same thing obviously cannot be said of Juliet or Giselle or a swan, or other quintessential ballerina roles. So that's where I think she worked really well because she performed a “melting pot” with her dancers. In that sense, it was a kind of dancing model of an idealized, non-existent but aspirational liberal US modernity—it was for everybody. And although the communist Marxist idea was that art was for the masses, that's certainly not what the hegemonic communist high-dance form did. It was not what it performed.

DRQV: Now that you mention her embrace of this idea of dance as a celebration of the individual, we are approaching another dilemma I wanted to touch upon: her reliance on public monies and funds. As you note in the book, the United States Information Service (USIS) “recommended that arts programming not be associated with the State Department, or it would appear state-sponsored and thus Communistic” (p. 75). More dramatically, she was under the growing shadow of Donderoism (and later, McCarthyism) in the scrutiny of funds assigned for cultural diplomacy. But, at the same time, Graham’s tours (and later, even her domestic operations) would have been unfeasible without state support. The CIA, embassies, and private benefactors thus became central for her project (as in Israel, for instance). Could you tell us more about how your work traces the political economy of public and private monies in some of her tours?

VP: My degree in Finance finally paid off with all of this because I was trained to follow the money as a hedge fund manager. One of my biggest revelations in this was that, number one, the Martha Graham Dance Company would not exist were it not for State Department tours. However, what was also fascinating to me was that the same can be said of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre—they would absolutely be bankrupt, gone, done, if it had not been for the State Department. The same is true for the American Ballet Theatre. Conversely, the New York City Ballet had its own amazing funding machine and did not need State Department funds to stay alive. It also had the Nutcracker. What my work reveals is this important network of financing that was used, I would say, really, as a “push-me/pull-you.” Graham knew how to navigate this network. For instance, she received the Medal of Freedom from Gerald Ford in a very savvy way. Because it was initially offered or suggested under the Nixon administration, but she was concerned about Spiro Agnew (and what would later erupt as the Watergate scandal). She knew that if she accepted the medal then, a picture of her would be taken with Nixon. So, she declined. She just had this political “sixth sense”—it was brilliant. When she received the Medal of Freedom, she claimed in her speech that her company survived the Great Depression on bank loans. Now, maybe she had friends in very high places, but the idea that during the Depression, Martha Graham had received bank loans in New York in order to fund a modern dance company seems interesting, to say the least. So, what she was saying (and this resonated with some ideas Ford wanted also trying to put through the legislature) was that funding for the arts also had to come also from private networks of people so that not all arts programming depended on the government, which would be “communistic.” She said she was a historic by-product of exactly the legislative arts agenda that Ford was pushing. I don’t think this was an accident.

She believed in philanthropy working with government. The American philanthropy that Tocqueville talks about and that is really important to the national ethos; to the humanities; to the sciences; to the arts (for better or for worse). So, there was both a political reason for her to take money from overt government sources, covert government sources, as well as foundations and wealthy individuals. It was deeply American. And then there was a practical reason —that somebody might give out! You have to stay on your feet. And these companies were always teetering. One of the really important sources of funding for her was her school. And she did lecture demonstrations where she would give a class in her dance technique. And there were Graham schools that sprouted up globally. Unfortunately, she didn’t make a franchise out of this (like, you know, Bikram yoga or Core Pilates nowadays). But it did mean that her center in New York was a place where people came to study after having trained in London, in Japan, India, and many other countries. And this was also an outlet for her dancers to make money and become teachers throughout the US and also internationally.

So, there were lots of different sources of funding, and what I found particularly interesting was depending on where she was, that was what was emphasized in tour programs and to the press. So particularly in the first tours in the in the 1950s, a lot of times there were these “Friendships Societies.” I've learned that whenever there is a “Friendship Society,” chances are that it involved some covert CIA funding. The programs almost never mentioned the State Department in the early days. The local Embassy also always had a little purse. She additionally relied on the largesse of women such as Bethsabée de Rothschild or Lila Acheson Wallace. I believe her way into the Sacklers and the Temple of Dendur performance at the opening of that Wing was through one of these women (I'm not entirely sure about that, but Lila Acheson Wallace would probably been the person who connected her to the Sacklers). So, there was this network of powerful, wealthy, philanthropic, women. This was unlike, for instance, the New York City Ballet, which had male networks seeded by Rockefeller-Harvard connections and later the Ford Foundation grants.

The funding that she received did not generally come from such male-dominated mega philanthropies. When she did try to get some of these grants, the ageism and the sexism of those large philanthropies prevented her from receiving funding. I found very, very nasty comments about her age in the Ford Foundation grant archives. There were also veiled references to her alcoholism, which indeed was a problem. There were even some hints that she was too close to Bethsabée. Men hinting to men. So, in general this funding dried up for her. But if the government needed her, they came back into the picture. In sum, she was very, very savvy to keep the buttons going all over the place. But this also absolutely suited US government.

In particular, with regard to the 1955 tour, people always thought that that last stop in Israel was funded by the State Department. Rothschild paid for every tour to Israel until Carter. Martha’s relationship to Israel could be an entire book. She constantly toured is Israel and had a very important school there. She stood by during wars. She even allowed the Rothschild company to perform her works, which had been a monopoly for the Graham company until she died. When the US wanted to promote ties to Israel openly, the State Department under Jimmy Carter sponsored the tour. State Department funding was subtle until it was needed to be otherwise. For example, the US Embassy would always host parties when Bethsabée paid for the tours—a back-door sign of US support for Israel.

DRQV: I was wondering if we could talk a little bit about your approach to primary sources. I found very inspiring how you not only draw from official sources all around the world, but also read them against the grain. In a way, you even read Graham against herself! She presents herself as apolitical, but you read her politics (and those of her patrons) back into the narrative. Could you tell us more about the challenges you faced—both logistically and intellectually—in your archival research?

VP: I think I'm naturally inclined to read against the grain. I was taught in an intellectual tradition that one never should believe what you read. My first political memory is peace marches and Nixon resigning on TV. I've had a lot of wonderful mentors, like Mary Marshall Clark (who runs the Columbia Center for Oral History Research). She taught us that you that you let the person speak, and you listen for the silences. And I found the same was true with foundation and official documents.

The other thing that forced me into this relentless pursuit mode with documents was the fact that the documents were not easily found, as I’ve said. So, I knew that that Eleanor Dulles had invited Martha Graham to perform in Berlin in 1957. I had the letter thanking her for performing along with an invitation. But there were no records in the US about this performance, no other records in Graham’s scrapbooks. So, I had to dig, and I ended up finding the documents related to the performance in an architects’ scrapbooks at Harvard. I thought of this because the performance in Berlin was related to the opening of a building. Then, what was completely fascinating to me (which apparently is something that is well known in the UK, Germany, and many other countries) is the US is not very good saving its records. I was oftentimes able to find US government documents only in foreign government archives. So that was true with regard to her performances in Berlin in 1957—the treasure trove of institutional documents and all reviews were in Berlin. But this is also true of Israel under Carter where there was a cultural agreement between Israel and Egypt signed right after her Carter performance (in many ways, her performance apparently laid the ground for it). But I could not find it the agreement in the US! Not at the National Archives, the Jimmy Carter Library, the Vice President’s papers, even his wife known as “Joan of Arts” only had hints about how Graham got to Reagan through Al Haig. But no tour documents. By contacting an Israeli tour manager through Graham dancers, I found the retired US State Department cultural attaché and interviewed her. And by going to Israel and interviewing Israeli diplomats, I was led to the government’s brokered agreement in Israel’s National Archives in English.

So, because Graham was in a sense, hidden in plain sight, and I knew that these things had taken place, the only thing I had to do to find the documentation was to travel and take oral histories. Now, this got me into the huge problem of language, because I speak English, and I read a little bit of French, and wrote a book in French. In theory, I passed my orals in Spanish. That's it. None of the foreign languages had any use for the study of Martha Graham at all. So, what I worked with is a firm belief that if you and I look at the same primary document, you and I are going to have two very different reads on that document. Again, probably because of my training as a youth in a communist/socialist school, I believe in the power of the collective. And I believe in the power of collective research. So, if you and I have different topics that are somehow related, and we go to an archive together, I may see things that will be of interest to you, you may see things that will be of interest to me, we may have common documents, and that it is a net win-win for both of us to share those documents and knowledge. So, I use a lot of work shares and exchanges and it was fantastic.

So, what I worked with is a firm belief that if you and I look at the same primary document, you and I are going to have two very different reads on that document. Again, probably because of my training as a youth in a communist/socialist school, I believe in the power of the collective. And I believe in the power of collective research. So, if you and I have different topics that are somehow related, and we go to an archive together, I may see things that will be of interest to you, you may see things that will be of interest to me, we may have common documents, and that it is a net win-win for both of us to share those documents and knowledge. So, I use a lot of work shares and exchanges and it was fantastic.

Now, of course, for that to work everyone in that research circle has to be ethical. That is where the Cold War Archives Research project comes in. There, other colleagues and I have been pushing for the creation of a common ethos of discussion and scholarship. Part of this is training new scholars in the best ways of the academic tradition. We emphasize proper citation. We teach our students that if you found a document for me, you can expect to find yourself in my footnotes. Attribution is fundamental for collective research—whether it's legally required, just a matter of courtesy, or part of a process of scholarly discussion and dialogue.

With that mantra, I was able to find partners in Poland, the former Yugoslavian archives, Germany, Israel, and Finland. Whether it was a workshare, or I got funding to hire people, the results of those partnerships were just incredible. Although you could do this remotely, what I found was that it was really important, even though I didn't speak Polish, to be in Poland. There was this instance when I was trying to find documents related to Virginia Innis Brown (a very important women who was an advisor to Eisenhower, though no one has really written anything about her despite the fact that she was a tremendous cultural diplomat and privately funded a lot of ballet. She was even given an award by Kennedy, but no one pays attention to that either). So, I asked the researcher in the Polish archives to help me find her in the files, and he said, “there is nothing about her.” I thought, that is very strange, and he replied, “Yes, there is only a destruction notice.” Wait, that is different! So we knew there was a file that had been destroyed in 1962, the year Martha went to Poland. That is interesting. Then he found an article that no one else had seen—not even the State Department, as far as I could tell, because the people in the State Department were not Polish. It was in an obscure arts magazine; the review was scathing, so maybe they didn’t want to see it! In the example, if we were on a Zoom meeting and he said, “there is no file,” I would understand there are no documents. But, by being there, I could see there was a file but that it had been emptied. So again, this goes back to the silences of the archives. The problem is that that kind of research takes money and funding. That is a big challenge. But by working together in cooperative groups this could be tackled. I would encourage everyone to work cooperatively with people you really feel you can trust.

DRQV: One last ambivalence that I would like to highlight is related to Graham’s status as a woman. As you note, despite her power, her age and gender haunted her throughout her career. Her life and work, as you put it, “expressed the paradoxes of powerful woman in Cold War America” (p. 8). Your account puts Graham in a network of powerful women who attempted to engage in politics despite the limitations imposed by their (our?) times. Chief among them were the United States first ladies, who from the East Wing of the White House supported Graham at crucial moments of her career. Could you tell us more about how your work resonates with other interventions in relation to gender in international history?

VP: One of the things that I like to think of myself as doing is excavating the histories of what I would call “big women.” We have “big man's history.” I would argue that actors such as Martha Graham, Eleanor Lansing Dulles (the subject of my next book), even Virginia Innis Brown, Lucia Chase (one of the founders of American Ballet Theatre), Lila Acheson Wallace (and her Reader's Digest fund) were “big women” because they were important and powerful. Instead of belonging to the University Club (like the big men), they were part of the Cosmopolitan Club (or other women's clubs). They didn’t go to Princeton to study, but they went to Bryn Mawr College or the Seven Sisters. To me, the important analyses of the networks of men as power brokers have set the stage for a similar analysis of women who were important Cold War actors. We just don't know their names! That is why we have to undertake an excavation process. So, it’s elitist as a study, but not because you’ve not heard of them. It’s an underground elite structure.

This is not the history of collective female emancipation or of feminists. As a matter of fact, most of these women—interestingly—who were born in the late 19th century or early 20th said: “I am not a feminist.” This is fascinating. They were power-brokers! They believed in the power of the individual; they grew up during the struggle for female suffrage. They saw what happened to the women's movement after suffrage and how it fractured. And they said, “I am an individual, I'm a human. And that's my power.” Which is quite subversive. Right? Quite interesting too. They did not like “bra burners,” but they were certainly liberated. So, I think that was really their stance, which I think we do need to respect if we look at their behavior. They behaved like feminists: Martha Graham ran her own company; was the star; the choreographer; she did not have children; she put her own family behind to pursue her career; she raised her own money. Moreover, she was ruthless when it came to casting and was very savvy working with governments. Yet, she said, “I'm not a feminist.” I think we have to look it, at these definitions, in the context of gender history.

DRQV: Our conversation resonates with the conversation I had with Professor Glenda Sluga on her book The Invention of International Order. I think the two of you are really showing, in different ways, that it is false to claim that women were not there. They were there, of course—it's just that we forgot about them, and the ways that we forget are important to explore too.

VP: The other thing that I am starting to explore (and not with Martha Graham, as she famously proclaimed: “center stage is wherever I am”) is the role of women who worked “behind the scenes.” Some of the other women—like Lila Acheson Wallace, Eleanor Dulles, Virginia Innis Brown, Bethsabée—could do the work that they did because they were tucked away behind the scenes. This applies to other women too, like Katherine Howard (who was very involved in the civil defense program). I could rattle off all of these names of women who had a very important role in shaping Cold War America and its legacy, but none of them stood center stage. If they did (and tried to displace the men), they would have been tossed out. Katherine Howard was physically tall, so when she spoke at podia she took her shoes off to appear smaller. She even titled her autobiography, With My Shoes Off! Think about Hillary Clinton. The second it looks like the First Lady is in charge of health care, everybody revolts; or when Betty Ford, who leveraged her early training with Graham as First Lady, got into trouble for pushing the Equal Rights Amendment. But if the First Lady merely supports the President, then people are all right with it. That's, I think, true today—so imagine fifty years ago. I argue that just as Martha denied so many things because they served to increase her power, these other women used gender norms as a cloak to mask their invincibility. Although in all cases, though shrewd and pragmatic and wildly successful, doing so took a personal toll on them. That’s where my new fascination with biography comes in.

[i] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_A._R._Brown

[ii] Diversion of Angels, https://vimeo.com/14503816?gclid=Cj0KCQjwpcOTBhCZARIsAEAYLuU1wSspk1oLjYvAmwCdKfuFgEajZ7S4l6SDdTU5IUJyXXsn2xeESRwaAvyOEALw_wcB; Martha Graham teaching, 1975, three years before I studied with her, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FuCbs25LGh0; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5t_Lt7DUPY

[iii] Night Journey, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y9fHayWO9bo.

[iv] www.victoria-phillips.global

[v] https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/politics-and-dance/

[vi] Lamentation, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I-lcFwPJUXQ&t=193s

[vii] Frontier, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E6RZsTme_vw