Thinking Big ... and Small About U.S. History in a Global Context with Daniel Immerwahr

Whether they know it or not, Americans are a people ruled by community organizers, indeed fascinated by them. Barack Obama, many will know, worked as a community organizer in Chicago for three years in the late 1980s, while former Secretary of State and 2016 Presidential hopeful Hilary Clinton wrote her thesis on the community organizer Saul Alinsky. The current slate of potential Republican challengers may not boast quite the same communitarian credentials – Scott Walker was a Boy Scout and Bobby Jindal a volunteer at LSU football games – but the once-touted David Petraeus was, of course, famous as a master of counterinsurgency strategy in Iraq and Afghanistan, a man who (prior to his resignation as CIA Director) was famed to have mastered the community scale as the proper war against Iraqi rebels and the Taliban. Fittingly for a nation that supposedly bowls alone, Americans are obsessed with community – what it was, how to get it back, indeed, how to develop it.

As our most recent guest to the Global History Forum, Daniel Immerwahr, shows, this American fascination with community is not some recent invention. Indeed, even as the scholarly literature on the United States in the world these days is in the midst of a focus on development in the Third World, typically the term ("development") means heavy infrastructure. "Dams are the temples of modern India," said post-independence Indian leader Jawaharlal Nehru, and the same could be said of the 21st century historiography of the United States in a global context. Yet as Immerwahr, an assistant professor of history at Northwestern University, shows in his recent book Thinking Small: The United States and the Lure of Community Development, this dream of large-scale development was always accompanied by a parallel drive to use the small scale – the group scale – of community development as a tool to guide Third World societies away from the temptations of Moscow and Beijing.

How did we forget this story? Given the prominence that the historiography today tends to assign to dams, power plants, and railroads, why did we lose the focus on community in America's outreach to the world? Most importantly, given that community development's accomplishments in both the Third World and in America itself are so ambiguous, why do Americans remained fascinated with it as a panacea for poverty? These are precisely the questions that were in our mind when we had the chance to speak with Professor Immerwahr about his latest work and his forthcoming projects on American international history.

•

We begin our conversation by reconstructing Immerwahr's journey to the discipline of history – a journey, he stresses, that was far from a forgone conclusion. Born outside of Philadelphia, Immerwahr grew up as the son of a philosophy professor (Dad) and a theater director (Mom). Conversations, he recalls, were oriented less around historical scholarship than "your standard liberal politics" – the closing of the local bookstore with the arrival of a chain store, for example. But Immerwahr dreamed of a future not necessarily oriented around books. He wanted to be a jazz musician, and hence, when the time came to think about where to go to university, he "assumed that New York City would offer a lot of opportunities in that regard." Soon, he was off to Manhattan to begin his freshman year at Columbia University.

The time in Morningside Heights, however, brought unexpected intellectual transformations. Immerwahr grew slowly interested in history through courses with historians of the United States like Eric Foner and Anders Stephanson, whose lectures he recalls as being among the most intellectually "juicy" on offer around the Columbia campus. Still, Immerwahr stresses, he remained equally anchored in the intellectual scene at Columbia Architectural School, where he took many classes and worked as a research assistant.

Ironically, however, it was through this seeming detour around history that he came to the discipline. Immerwahr recalls a conversation with Columbia architecture professor Gwendolyn Wright (perhaps most famous for her work with PBS' History Detectives), with whom he had been taking a course on colonial and official architecture. Immerwahr was particularly interested in American official architecture in Hawaii, a U.S. state since 1959, but one with an especially complex "pre-national" history: the island archipelago was an independent monarchy until 1893, but following a series of coups, it became an American-aligned Republic and then a Territory in the late 1890s. If we accept as a given that colonial or imperial power expresses itself in part through architecture, what do we find in a place like Hawaii, at one incontrovertibly a part of the United States and yet with an imperial past? What makes it different from a place like the Philippines, from Alaska, or from the "core" United States of New York, Virginia, etc.?

Full of such questions, Immerwahr was promptly directed by Wright to take a seat on the New York City Subway and travel south, to NYU, to speak with Wright's husband, who taught there. Immerwahr made the appointment, but little did he know that Wright's husband was Thomas Bender, one of the most influential scholars in the historiography of the United States and the world. Indeed, Bender was about to come out with the anthology Rethinking American History in a Global Age, his rallying cry for the need to place American history in a global context. Dazzled by the conversation with the NYU scholar and soon in possession of a Marshall Scholarship to study at Cambridge University, in the UK, Immerwahr soon had a plan: he would find a way to write about the United States in the world, but would take the time in the United Kingdom to build up his competency in other areas. It was no longer paradoxical to suppose that delving into the history of the Philippines' agrarian regime, or conjugating Hindi verbs, was irrelevant to the making of a historian of the United States.

Soon enough, then, Immerwahr was back in the United States, beginning a PhD program at Berkeley, taken under the wing of historian David Hollinger. Immerwahr praises his former mentor as a polymath: while perhaps primarily known as a scholar of American intellectual history, Hollinger regularly advised theses outside of a normal person's comfort zone. By the late 1990s, modernization theory became an area of especial interest for Hollinger and his advisees, and some of the pioneering work in the field – Nils Gilman'sMandarins of the Future and David Engerman'sModernization From the Other Shore – began life as a dissertation at UC-Berkeley.

Immerwahr came to the campus initially thinking that he would work on connections between African-Americans and South Asians, but soon realized that he was not alone in the field: Nico Slate, a historian of social movements in the USA and India now at Carnegie Mellon but then a graduate student at Harvard, had already begun work on the topic. (Slate's dissertation was later published as Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India with Harvard University Press in 2012.) Immerwahr had the wisdom to divert his work on the subject into an article, but his seminar discussions were pushing him in a different direction. In all of the scholarly arguments about the history of modernization, he stresses, there was "the fantasy of connecting the seminar room with the dam." Students remained intrigued by the JFK and LBJ years in particular as a time when academic expertise was fused into the policymaking apparatus in a way not seen before, or, arguably, since. The Indian dam on the Harvard or MIT chalkboard, it seemed, could materialize into concrete and steel with impressive alacrity.

Over time, however, Immerwahr noticed in the documentary record not only the "slips between the cup and the lip," when academic ideas about development or modernization were notcarried out in the field, but also a more fundamental methodological problem.The closer one looked at how development projects were actually implemented, the more one noticed a counter-discourse of communitarianism as a foil to the assumed prevailing obsession with dams, mechanized agriculture, and electrification. Administrators and scholars championed not the only factory, but also the village council, as the primal space for post-colonial nations like India or the Philippines. Not only that, but the more Immerwahr read within US intellectual history, the more he saw how deeply committed some midcentury intellectuals were to the idea of community. What if the way to write the history of developmentwas not through figures like Walt Rostow, nor through a history of steel plants in India, but through the unlikely, indeed seemingly "unmodernized" site of the village?

Reflections like these launched Immerwahr onto an intellectual journey that culminated in Thinking Small. While Immerwahr's tale would seem to have more to do with America in the world than America at home, he begins the story, refreshingly, in the Depression-era United States. Charlie Chaplin is in the theaters, factories are shut for want of work, and the work looks, with equal parts intrigue and fear, towards the mass industrializing totalitarian countries of Stalin's Soviet Union and, to, a lesser extent, Hitler's Germany. As Immerwahr reminds us, however, the ethos of the time among many an American intellectual and future social scientist was not that of the Five-Year Plan or of trade unionism, but rather a deep skepticism towards bureaucracy, industry, and mass society. Consider, for example, American author E.B. White. White is perhaps best known for his works in children's literature, but he was squarely legible as an an intellectual of New York City for much of the 1920s, eventually departing, as does his talking mouse Stuart Little, to the countryside – virtuous, free, democratic, and free of the smoke, hubbub, and gnashing gears of urban, industrial life. Many other intellectuals, often originally coming from sympathies with the Communist Party, make a similar departure from the big city towards "Our Town."

Yet as Immerwahr shows, the turn from big to small was not just a phenomenon restricted to literary intellectuals. The 1930s and 1940s saw a rising interest in the small group – not the masses – as a central unit of social analysis. Jacob Levy Moreno, born in the Kingdom of Romania and trained in Freud's Vienna but later an arrival to the United States, established the subdiscipline of "sociometry" in the United States, arguing (on the basis of research with Viennese prostates and delinquent American girls) that identity emerged not just sui generis, but through interactions in small groups. Sociologists as much as policymakers had to look beyond the mass man, "the man who can be exchanged" and instead focus on how society operated as a system through (however idealized) small and voluntary organizations. His ideas found traction, and a perch at Columbia University allowed him some influence among not just academics but intellectual circles dissatisfied, like White, with industrial society. In an era where societies of mass mobilization – Germany, Russia – seemed to have the wind at their back, could not the group offer an escape from mass mediocrity and into a great society?

"Groupism," as David Riesman called it, soon found applications in a variety of contexts. Researchers at Harvard Business School, through the so-called Hawthorne Studies, argued that managers had to view their workers not just as cogs or Taylorist variables, but as individuals who could be comforted through semi-democratic forms of engagement (read: not unions) with management. Arthur Schlesinger's The Vital Center argued for more American "vitality" that was to be achieved through rejuvenated voluntary associations. Yet in response to this vision, a kind of Bowling Alone for the 1950s, authors like Riesman and William Whyte pushed back. Too much focus on "outer-directed" individuals who fit well into group life could dull down the conflict and political clash that was healthy to a democratic society, felt Riesman. And in his 1956 The Organization Man, Whyte similarly pondered whether so much sociability was a good thing. Trained to get along in what were vanilla at best and boring at worst social organizations, marriages, and Fordist corporations, the American man "is imprisoned in brotherhood," wrote Whyte. More individualism was necessary to get the best out of man.

Still, as Immerwahr explores in the book's second chapter, ideas about the virtue of the group found application in development projects at home. In what reads like the flip side to Tufts historian (and Toynbee Foundation Trustee) David Ekbladh'sThe Great American Mission, Immerwahr shows how the ballyhooed bigness of the Tennessee Valley Association was accompanied by no small amount of … smallness. Operating above the bureaucratic labyrinth at work in Tennessee was the Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Agricultural Economics, whose Division of Farm Population and Rural Welfare was stuffed with rural sociologists interested in small, self-sufficient towns. And from 1938-42, the BAE's programs (not limited to the TVA watershed) coordinated numerous local planning committees of farmers, comprising around 200,000 people total, to discuss land use and long-term economic projects in a purportedly democratic method.

Not only that, the United States Department of Agriculture chipped in by inaugurating a "Schools of Philosophy Program" designed to educate would-be bumpkins in the deeper arts of democratic life. Indeed, no less than pioneering historian Charles Beard, along with Frank Knight, Eleanor Roosevelt, W. E. B. Du Bois, and others, gave talks to farmers and USDA workers to expand their minds and, broadly, turn American agrarian culture away from an obsession with mere production. But the BAE's farm planning committees were scrapped in 1942, and another attempt at communitarian organization – the application of small group exercises and committee decision-making among Japanese internees– was similarly ambiguous in its results. By the 1940s, then, communitarian ideology boasted few significant accomplishments in its limited zones of application, and there was little to suggest that it would have much use or reception outside of the United States.

Until, that is, the Cold War. At precisely the same time that increased agricultural mechanization was making the expertise of ex-TVA types pointless at home, what was called the developing world seemed to offer a fertile field to test communitarian techniques. The United States had to duke it out with the Soviet Union for influence in theaters like India, like Indochina, like Southeast Asia, and with precious few people who actually knew much about the places themselves, people who were thought to know something about the process of development itself – soil consultants, forest managers and, yes, community managers – were soon dispatched to places like India and Philippines, countries which are the subjects of the next two chapters of Thinking Small.

In spite of its enormous rural population, India might seem like an unusual place for the community development paratroopers to land. Typically, explains Immerwahr, "students of Indian history have regarded policymaking under Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru as profoundly modernist, dedicated to a faith in science, a technocratic style of politics, and a zeal for high-impact infrastructural projects. Indeed, historians are fond of quoting Nehru's description of dams as the "temples of modern India." Perhaps the most sophisticated case in this direction comes from historian Partha Chatterjee, who has argued that the post-colonial Nehruvian state represented a continuation of its colonial predecessor, insofar as it (in Immerwahr's words) "inherited and then reproduced the same Enlightenment-derived mental habits of the British Empire." If both Gandhi and the Indian village were interested in hand-weaving and self-sufficiency (think of the charkha on pre-independence flags of India, or the fact that the flag today is legally mandated to be made out of hand-spun khadi, a hemp-based cloth), then Nehru was interested in shameless modernization – whether from American, Soviet, or German mentors.

So, where does the village come into this? As Immerwahr shows, during the late 1940s and early 1950s, some Americans had embraced the village and the group scale as an optimal one to further healthy national or post-colonial development. University of Chicago anthropologist Robert Redfield had, under the influence of Chicago sociologists Robert E. Park and Robert Burgess, grown interested in how "folk societies" transform into urban ones. And while Redfield avoided the worst tendencies to romanticize "the village" or the rural as a virtuous, alternative field for human flourishing in contrast to the decadent city, he retained sympathy for village ways as he embarked on field studies in Mexico in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. Based on work in Chan Kom and Tepoztlán, he came to the conclusion that villages' economies could be integrated into larger national market transformations without simply dissolving or coming apart. "The trick," summarizes Immerwahr, "was to find a way to embed development-enabling values within the Tepoztláns of the world via some gradual and nondisruptive process."

But could this dissenting American tendency towards groupism find contact with similar patterns of thought in the Global South? Perhaps. At around the same time, Indian anthropologists like M.N. Srinavas argued that the Indian village was a similar repository of folk values – not just in the sense of ostensibly "backwards" rural ways actually being virtuous, but also the idea of the Indian village, from Bengal to Tamil Nadu as a cell of "Sanskritized" India-wide culture, the result of a 2,000-year process via which Brahmin Hindus had impressed their (changing) cultural norms on the population write large. Healthy development would thus mean not just a crypto-Stalinist state issuing commands and decrees down onto the countryside, but rather a two-way conversation between development ministries and social scientists and this more primal village tradition.

Hence, even as figures like Redfield and Srinavas would always clash with more famous figures like Walt Rostow (in the USA) or P.C. Mahalonobis (in India) – both affiliated more with top-down planning – the community development types had found a language that would allow them to collaborate with the developmentalist state. Communitarians needed the post-colonial developmentalist state to fund and institutionalize the paradoxical project of village development as a state-led project; modernizers needed the community development programs both as a pragmatic initiative in overwhelmingly rural societies and, arguably, as an alibi against shrewd critics of the independent state like Chatterjee.

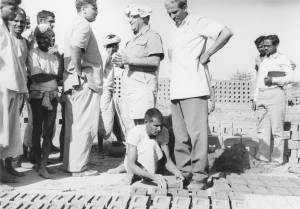

In any event, India soon became the test site for thousands of "Peasantvilles." Of course, figures like Rabindranath Tagore and, of course, Gandhi, had experimented with village development before independence. The key American figure was Albert Mayer, a planner of "superblocks" and Green Belt towns for the New York metropolitan area, who had met Nehru during a World War-II era trip to build airstrips there. Nehru liked Mayer's approach towards holistic urban and rural development, and opened doors and funding channels for Mayer. Communitarians known to Mayer from the 1940s (some of whom had worked on the Japanese internment camp project) soon arrived in Etawah, a district in Uttar Pradesh that became a test site for a new bottom-up approach to development. Within five or so years, villages in the district boasted hundreds of new brick kilns, community centers, and threshers, most built and funded by locals and with hardly any outside technology used. "The achievement," in short, "was not material but sociological."

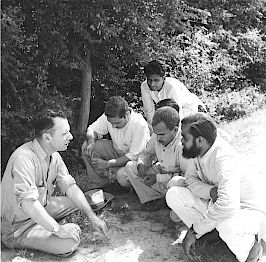

Soon, the US government and the Ford Foundation joined the show, making Etawah into a potential model for all of the Subcontinent. Ambassador Chester Bowles, keenly interested in the Third World, feared a Maoist-style peasant uprising in the Subcontinent and had $52 million in development funds to spend. Village development seemed promising, and so under a 1952 Indo-U.S. Technical Agreement, 16,500 villages became test sites for community development projects. By 1965, the program encompassed every village in India. Village-level community development workers would recruit "natural leaders" among villages who could call meetings and initiate projects – a better-funded version of the 1930s TVA programs. State governments would provide some resources, like seeds, livestock, and technical guidance, but the bulk of materials, much less what villages were actually supposed to do with the stuff, was to come from council meetings.

All of this took place not only alongside a parallel (if also better chronicled) drive for industrialization led by the Indian Planning Commission, and a spectacular rethinking of Indian administration itself. Indeed, with the backing of Gandhians, Hindu nationalists, and socialists, the community scale became a principle for the entire planning apparatus itself. Under the so-called panchayati raj (reign of village councils) scheme, first introduced in Rajasthan in 1959, villages themselves (or rather a byzantine three-tiered system of councils, panchayats) would be the source of development plans supposedly emanating from the "felt needs" of villagers. The dreams of figures like Redfield and Srinavas had, it seemed, found institutional expression.

And yet there were several troubling elements to the entire vision. People like Mayer tended to view village life through rose-colored lenses, writing off caste privileges or crushing patriarchy as sources of stability or mere endogenous factors that developmental professionals had to accept and move on from. Indian peasants, often landless and indebted, were readily analogized with the virtuous American homesteader, and less often with the sharecropping African-American or produce-picking Mexican laborer to whom they arguably bore greater resemblance. Most of the "natural leaders" deputized into village councils were Brahmins, and less than one percent were agricultural laborers. Untouchables remained barely integrated into the system at all.

More fundamentally, explains Immerwahr, there was a tendency to write off the experience of the Indian state Kerala (home of an elected Communist government) as idiosyncratic, irrelevant, or even dangerous to the rest of India's needs. There, even though Keralan Communist and (after 1957) Chief Minister E.M.S. Namboodiripad came from a Marxist-Leninist background of hierarchical Party discipline and a suspicion of "the idiocy of village life," the Keralan state government undertook a large program of administrative (not just developmental) decentralization. Granted, Kerala was known for not having villages, so to speak, in the same sociological sense as the rest of India – its "extraordinarily dense population was spread out evenly across the countryside like jam on toast, rather than clustered in villages, like mounds of sugar." From this point of view, instituting administrative councils could be seen as a bid on Namboodiripad's part to engage the (hopefully) left-wing, partisan peasantry in the machinery of state.

But the experiment remained largely a counterfactual one: although the Communists of Kerala pushed through land reform bills during their two years in power, the government was dissolved under Nehru's invocation of emergency power. The dream of structural change of the Indian countryside through the Left, through land reform, remained abortive.

And yet the vision that figures like Bowles hoped would make the Left's dream irrelevant was itself quickly embattled. By the late 1950s, grain shortages and with it, hunger, came to occupy primacy in discussions among both Indian planners, UN types, and American élites about the future of India. In 1960, the Ministry of Community development ordered village-level workers to devote themselves almost exclusively to agricultural questions, a clear shift away from the earlier, more holistic vision. And when Nehru died in 1964, the program lost perhaps its most important patron. Nehru's successor Lal Bahadur Shastri, displayed little enthusiasm for the program, but it was Nehru's daughter, Indira Gandhi, who effectively dismantled the program, moving it under the aegis of the Ministry of Agriculture. Central outlays for community development grants drooped, forcing local officers to become more dependent on unsympathetic (at best) and broke (at worst) state governments. Gandhi's state of emergency (1975-77) finally gutted the nod towards decentralization (developmentally if not politically) that panchayati raj had symbolized.

With such a record behind it – limited material accomplishments and an arguable retrenchment of rural élites interests – community development seemed to have a rather undistinguished record already by the 1950s. That, however, makes the need to explain its journey to the Philippines, a former U.S. colony and stalwart Cold War ally, even more important. Immerwahr sees the Philippines as a darker application of communitarianism. If in India the surprise was that the village could be reactionary at all, in the Philippines this was very much the point. The Philippines had been occupied by the Japanese in 1941, forcing Washington to reverse its traditional policy towards its colony, supporting Hukguerrillas against Tokyo's occupation forces – a shift from its previous stance of normally allying with the landlord class against the peasants. After independence, however, a landless peasantry threatened US-supported President Elipidio Quirino. With China under the control of Mao and much of the rest of Southeast Asia under threat of Communist, anti-colonial penetration, US officials seemed to lack for a middle way between land reform and more violence.

The postcolonial island nation thus became a test site for community development. One of the key figures was Edward Lansdale, later famous as one of the chief architects of Ngo Dinh Diem's policy strategy in South Vietnam, but at the name an obscure former advertising executive and CIA officer. The problem, argued Lansdale, was that the Huks were dissatisfied not with their lack of land, but rather with the ruling style of the Quirino government and the oligarchy that had been Washington's preferred lever on the populous country for decades. Finding an interlocutor in Ramon Magsaysay, Lansdale argued that peace in the countryside could be won not through rifles, not through land redistribution, but through community. Bringing on former Asian development types like Y.C. James Yen, Lansdale helped launch an Economic Development Corps program for the Philippines. It was really more of a propaganda program than the resettlement scheme it purported to be, but deployed alongside napalm campaigns elsewhere in the Philippines(Magsaysay was Minister of Defense throughout) Lansdale managed to rebrand the military man as a proponent of a middle path. Magsaysay offered the United States an appealing package of winning the allegiance of the common people while still remaining basically deferential to Washington and the Philippine oligarchy. Not Maoism, but a reinvented American clientelism represented the future of the region.

The precedents were set for a new kind of US-Philippines relationship. Washington officially abandoned its support for land reform, and Magsaysay was elected President in 1953. Empowered, he appointed one Ramon Binamira in charge of a national Community Development Planning Council, which soon morphed into a unified development agency (PACD) that placed community development at the center of its development projects. Unlike in India, however, there was little of an indigenous tradition of communitarianism actually sympathetic to peasants to draw on, and so – with CIA money greasing the wheels in the background – PACD sponsored tens of thousands of small village projects around the country. Communities would fund half of projects; PACD, the other half. The final goal, similar to the panchayati raj in India, was political decentralization, albeit with the tacit understandings that barrio councils (village councils) would not challenge Manila's wishes.

And yet conflicts emerged. Few villagers participated in elections for the barrio councils, and barrio council leaders (typically from well-to-do backgrounds) did not always want projects that PACD proposed. Like in India, the introduction of community development happened at precisely the same time that concerns of hunger mounted. The Filipino economy stalled during the early 1960s, and incoming inequality grew. And once Magsaysay died in a plane crash in 1957 (along with one of Yen's lieutenants) the program lacked a genuine Filipino patron. By the mid-1960s, when Ferdinand Marcos was elected President, it was the Green Revolution and not community development that promised to deliver results. And as Marcos established a dictatorial regime in the country, the legacy of the PACD – a vertical line of control from the capital into villages – and US support for dictators gave him a way to extend his personal dictatorship into the countryside in a way that old US-supported colonial oligarchs could scarcely have dreamed of. The PACD system became rife with bribery and patronage appointments, and so a system designed to buffer right-wing regimes from the countryside linked it with them.

As Immerwahr explains in the rest of Thinking Small – which also delves into the ironic return of community development to the US inner city in the 1960s – these episodes demand not only chronicling but confrontation today. When it comes to foreign policy, there can too often reign the perception that the United States' Cold War adventures really only went wrong "once modernization came to town," as Immerwahr puts it. Washington's intentions, the story goes, were good; it was only when too much concrete was laid, too much bureaucracy transplanted, and, yes, too much napalm dropped on villages, that the justified mission of anti-Communism went pear-shaped. Perhaps no other figure captures this myth like Edward Lansdale himself, whose protege Diem sought (in Lansdale's narration) to implement a community development strategy in South Vietnam until he was killed in a generals' coup (conducted with tacit US support) in 1963. This sense that the war – not just Vietnam but any war – could have been one with a lighter footprint played an important role in the rise of General David Petraeus, whose manual on counterinsurgency seemed to provide a book of secrets to conducting imperial war in Mesopotamia and the Hindu Kush … with the support of communities and locals. And yet there was, and is, precious little evidence that a focus on the small scale is more militarily effective, much less actually democratic, when it comes to support for client states.

The same, stresses Immerwahr, is also true for the domestic American context. Great Society initiatives targeted at "community action" may have been well-intentioned, but they ran across any number of stumbling blocks not fundamentally different from those encountered in Etawah or the Philippines. Throughout the 1960s, American cultural was saturated with a certain romanticized image of the neighborhood or the community as an ideal scale for human interaction – think Jane Jacobs, or even Sesame Street – but this notion of the American city as a warden of urban villages was based on obsolete stereotypes about white ethnic communities that had already long retreated from cities like Newark, Detroit, or St. Louis. By the times such programs launched, writes Immerwahr, "areas that had formerly been well-rounded neighborhoods containing a diversity of functions increasingly came to resemble internment camps for the dispossessed."

More than that, federal bureaucracies aimed to sidestep supposedly out-of-touch mayoral offices, but were surprised to discover that the urban poor were, well, angry. Community action funds went to institutions like Harlem's Black Arts Theater run by LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka), a man who described his political philosophy as "hate whitey." Federal mandates to have "maximum feasible participation" of the poor in their community management necessarily meant that Washington agencies would have to come to terms with people who had a very different conception of community than the one intended for them.

Tellingly, it was during this very period that the phrase "the black community" (odd when used in any other context, like "the white community") came into prominence, articulated by revolutionaries like Huey Newton. Long exploited and dominated by White America, figures like Newton argued, African-Americans needed to escape the nation-state (irrelevant in an interdependent world, anyway) and forge links with other oppressed communities around the world. The point of community development had been to turn the Third World – and maybe even the American city – into a planet of Etawahs, but once applied at home, places like Oakland increasingly resembled less India or the Philippines, and more China.

This episode, however, serves as reminder of how skeptical Americans ought to be towards calls for community development as a solution today for the beleaguered inner city. Newton's calls for the federal government to get its hands out of Oakland has been modestly successful, as since the mid-1970s "community development" in the United States increasingly means Community Development Corporations, entities that resemble more real estate development offices than Baraka's Black Arts Theatre.

More than that, even as the federal government has devolved control of important matters back to local communities since the 1970s (indirectly so in Department of Education cuts and property tax funding of schools), African-American gains of territorial control, as it were, of stretches of Newark, Detroit, the South Side of Chicago, and Oakland arguably means little in light of the suburbanization of economic geography and the growing concentration of wealth over the same period. African-American self-determination, as it were, meant little if it was accompanied by plummeting budgets and deindustrialization. Ironically, today Oakland is witnessing a black exodus as a new tide of white and Asian-American wealth gentrifies parts of the former Black Panther stronghold. Newton does not bear responsibility for the exogenous factors that transformed his dream for the black city into a phantasmagoria of pour-over organic coffee and gluten-free vegan restaurants, of course. But given that some of said coffee may well come from plantations in Kerala – home to the genuine if stillborn experiment with land reform and hard choices – the career of America's encounter with community development abroad and at home seems especially sad.

Sad, but not necessarily hopeless. The point of Thinking Small isn't to heap scorn on community development as a project, or to say that communities in America are doomed to some inexorable path of bureaucratic anonymity or (more likely) inescapable economic stratification and ghettoization. Rather, as he stresses in the conclusion, it's that any escape to the community scale, without hard choices accompanying it, has already been tried as a development solution. Tried, and failed. Rather than viewing community action as a novel approach or qualification for domestic development or foreign policy, we need to recognize that these debates were already staged more than fifty years ago.

Maybe there is something worth rescuing in that tradition. But, stresses Immerwahr, "community" by itself, however attractive-sounding, means little as a political project without hard choices – hard economic choices. In the case of the Cold War, that meant land reform. In the case of the American inner city, it might have meant reparations. Today, as Immerwahr sees it, the great struggle where the slogan of community threatens to derail respectable liberal opinion is that of global warming. We may like to think, à la E.B. White, that an escape from the smoggy city and the urban dinner table, loaded with hormone-injected chicken breasts, can reduce carbon emissions and save the planet. We like to think, in short, that in the absence of true collective action (i.e. politics on the national or international scale), the community of farmer's markets and organic farms may save us.

They won't, however, at least not alone. (Immerwahr also puts his royalties where his mouth is – all proceeds from sales of Thinking Small are donated to 350.org, a global warming awareness NGO). Without the hard political choices of carbon taxes, argues Immerwahr, that only national governments can implement or follow (if suggested by the UN), the beaches of Kerala and the shores of the Philippines may come under water, and the farmers of places like Etawah may be under increased duress as temperature rises. Politics, in short, not community, can save us. The community organizers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.

•

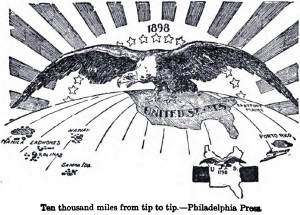

Exciting as Thinking Small is, it only represents the first of what are likely to be many works that promise to challenge the way scholars and citizens think about the history of the United States in the world. Immerwahr explains that he is already at work on a second book project, tentatively entitled How to Hide an Empire: Geography and Power in the Greater United States.

"Greater United States?" Attentive readers might wonder at the neologism, but that's precisely the intellectual intervention Immerwahr hopes to stage in his coming work. He explains that his interest in the project that became Thinking Small grew out of an interest in India, but that upon completing the book, he remained fascinated by the history of the Philippines, in particular its complicated and, too often, insufficiently explored, imbrication in American history. As much for his own enlightenment as for the enlightenment of others, Immerwahr devoured his way through the scholarship on the island nation and began putting together a piece titled "Everything You Wanted to Know About the Philippines But Were Afraid to Ask."

The point of Immerwahr's investigations wasn't just that American history is enmeshed with the history of the Philippines, but that the distinction itself was a methodological blinder that historians needed to free themselves of. "What if," Immerwahr says, "instead of writing about the Philippines as part of the history of foreign relations, we instead considered it part of national history? And what if, when we talked about the United States, we didn't just talk about the continguous part, but all of the land under US jurisdiction?" This is what Immerwahr means by the Greater United States – places like Alaska, Hawaii, the Philippines, Diego Garcia, or Bagram Airbase: points, as Immerwahr sees it, in the story of the United States going from having the world's fourth-largest empire that annexed territories and populations to a huge empire that, nonetheless, displays little interestin formally annexing territories. "Broadly," Immerwahr says, "the story is one of the U.S. going from a country that conquers territory then governs it, to one in which U.S. power infiltrates a huge number of spaces – black sites, say – but emphatically disavows not only its possession of these places but, especially, the extension of U.S. jurisdiction to these places."

How does one write the history of the Greater United States? Of course, Immerwahr intends to spend time in some of the usual archives and by reading collections like Foreign Relations of the United States. But, he stresses, he wants to avoid the typical archival bug, even fetish, that can take hold of historians. "A lot of the time," he explains, "the story we tell is, 'We thought X but I found Y. But that's not quite true. The real difference is analysis – the story we take into our heads that then guides what we look for in the archives." Only, in short, by thinking Z do we find Y, or rather, the archive that Y is in.

More concretely, Immerwahr has begun working with the archives of the little-known Division of Territories and Island Possessions,a unit of the Department of the Interior. The military is another big player in this story, too. Immerwahr notes that the U.S. military has, at least since the mid-20th century and probably before, been one of the largest purchasers of goods of any institution in the world, and could dictate industrial and commercial standards far and wide, creating a shadow empire of standards – food safety, power plugs, containers … – in its wake. The ripples left by the extra-territorial US empire were great indeed.

"As I see it," explains Immerwahr, "some of the most exciting new work in U.S. foreign relations is moving beyond the study of ideas and intentions toward the study of infrastructure. It's not just Winkler. That's what Brian DeLay at Berkeley is doing, too, in his research into who has guns in the nineteenth century. Emily Rosenberg's Financial Missionaries to the World is a terrific portrait of what it takes to build the financial infrastructure that the US requires to project power abroad in the twentieth century. I'd mention further mention Kate Epstein at Rutgers and her work on the hegemonic transition, Jenifer Van Vleck's research on aviation and, now, engineers, and Bill Rankin's forthcoming book about GPS and navigational technologies. What's emerging is a story about how the postwar world was build, and how the United States managed to install itself at the center of it."

•

We leave our conversation with Immerwahr reminded of the critical eye that history can cast on familiar subjects. What once appeared as a rustic, traditional Indian village turns out to be a side of applied social science; what once appeared to be a straightforward map of the United States (Hawaii and Alaska cordoned off in separately scaled boxes) turns out to be a larger, more capacious, history of empire and the changing meaning of territoriality in the twentieth century. We heartily recommend Thinking Small to readers, and know that we are not alone in following this historian of the United States in the world as he charts out his ongoing project. We thank Daniel Immerwahr for sitting down with us for this installment of the Global History Forum.