Archival Reflections—Dewi Sukarno Goes to London, or How to Handle an Indonesian VIP during Konfrontasi

By Giulia Garbagni (University of Cambridge)

Researching international history is a time-consuming, laborious business that requires the constant cross-checking of documents often held at archives located on the other side of the world. Sometimes, however, archives present the researcher with a neatly packaged gift: an anecdote that, in a few dozen of pages, vividly brings to life the odd situations that diplomats of the past had to tackle. This is the case for one folder of British Foreign Office records (FO 371/180366) held at the National Archives in Kew, which deals with the private visit to the UK by the third wife of Indonesian President Sukarno, Dewi, in June 1965. Against the backdrop of the tense diplomatic standoff between Indonesia and Malaysia—deemed by Sukarno an unacceptable iteration of British neo-colonialism—Dewi’s travels offer a much lighter, and at times even comedic, insight into British-Indonesian relations at the time. British officers, determined to make a good first impression on Dewi to soften her bellicose husband, quickly found themselves attending to out-of-the-ordinary tasks: scrambling to find a “young enough” companion for having tea with Dewi, infiltrating a wedding reception to gather information on her, and even disposing of an unwanted gift that Dewi brought for none other than Queen Elizabeth II.

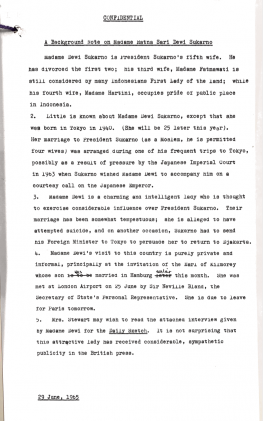

At the height of the Indonesia-Malaysia conflict (commonly known as Konfrontasi), in late June 1965, Sukarno’s Japanese-born wife, Ratna Sari Dewi Sukarno, set off to London. Accompanied by an entourage consisting of the wife of the Indonesian Education Minister, popular film star Baby Huwai, two police officers and a Japanese "beautician,”[1] Dewi was going to attend the wedding of a close friend. Despite the private nature of the visit, the Foreign Office immediately paid close attention to Dewi’s movements, well aware of the “restraining influence” she was said to exercise on Sukarno.[2] Dewi, née Naoko Nemoto, was a relatively new face in Indonesian politics, having become Sukarno’s third wife at the age of 22, in 1962. She had been introduced to him in 1959 by Kubo Masao, a shrewd Japanese businessman anxious to see his company, the Tōnichi Trading Inc, awarded lucrative reparation contracts in Indonesia.[3] The Japanese diplomats in London described her to their British counterparts as coming from “a fairly good Japanese middle-class family”[4]—omitting her working-class background and her previous employment as hostess at the Copacabana, a popular expat bar in Akasaka, Tokyo.[5]

The British were well aware that Sukarno’s hostility towards the UK was “unlikely to be mitigated by small courtesies to his wife.”[6] However, they did not discount either the potential impact that “a chivalrous gesture”[7] could have on making a good impression on such an influential guest—all the more so considering not only that Sukarno “can be strongly influenced by personal considerations,” but also that the US Embassy, among others, had “accustomed him to such sycophancy.”[8] Therefore, the Foreign Office’s Protocol Department and the South East Asia Department recommended that Mary Wilson, wife of Prime Minister Harold Wilson, send Dewi a bunch of flowers to the Hilton Hotel, where she was staying.[9] Other possibilities considered included sending someone to the airport at Dewi’s arrival, or even having both Mrs. Wilson and Mary Stewart (wife of Foreign Secretary Michael Stewart) invite her to tea.[10] Sir Neville Bland, former British Ambassador to the Netherlands, was eventually sent to meet Dewi at London Airport on the afternoon of 25 June as “personal representative” of the Secretary of State.[11] As for organizing a meeting between Dewi and the spouse of a senior staff of the Foreign Office, “[t]he difficulty is to find a wife who is not at least twice as old as Madame Dewi”[12]—quite a tricky task, considering that the Indonesian First Lady was only 25 years old. The tea option was quickly dropped.

The reason for Dewi’s visit was the wedding reception of the son of the Earl of Kilmorey with the daughter of John Gairdner, a Thai-British businessman once stationed in Jakarta and a close friend of Dewi’s.[13] The diplomat A. A. Golds from the Foreign Office made sure to attend the reception too. As he recorded, Dewi arrived with the fashionable delay of one hour, “dressed in what I am assured was a superb Balmain dress” and “smothered in pearls.”[14] Dewi’s attendance of the reception caused quite some talk in Jakarta. Some diplomats even speculated that the reception, which had been arranged a few weeks after the actual wedding, “was obviously an excuse to enable Madame Dewi to visit London for other reasons,” advancing the idea that her trip had a “political purpose.”[15]

Dewi’s presence caused some trouble in London too. For instance, several members of the Kilmorey family boycotted the celebrations “because of the Indonesian contact,” while Lord Kilmorey himself was “not altogether approving” but tacitly allowed her presence.[16] Moreover, Lord Kilmorey even confessed to Golds that he had felt “somewhat embarrassed” when Dewi requested his advice on how to deliver a personal gift she had brought for the Queen—which he described as a “Balinese ebony stand of great hideousness.”[17]

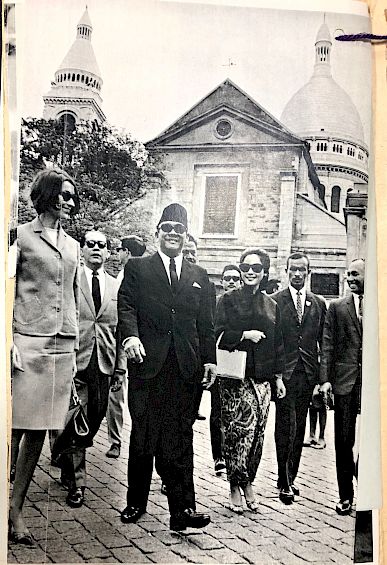

As for Dewi, she clearly enjoyed her time in London before joining her husband in Paris (see picture) and Vienna (where Sukarno regularly met his private doctor). As Golds gathered at the reception, she did “a lot of shopping” and made “a thorough round of the London night clubs”—gladly escaping the official events organized for her by the Indonesian Embassy (such as a visit to a children’s hospital) to meet “her English friends for private jollifications.”[18] While it did little to sway the anti-neocolonialist rhetoric of Sukarno, the handling of Dewi’s visit was a thorough success for the Foreign Office, with the Indonesian Chargé d’Affaires in London sending an official note of appreciation for the cooperation “so freely made available.”[19]

Figures:

- After her private visit to London, Dewi joined her husband in Paris: here they are pictured in front of the Sacré-Coeur Basilica, in Montmartre. Newspaper cutting from Paris Match of 17 July 1965, attached to telegram from Paris to Foreign Office, 21 July 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

- ‘A Background Note on Madame Ratna Sari Dewi Sukarno’, attached to telegram from J. E. Cable to Private Secretary of Mrs Stewart (wife of Foreign Secretary Michael Stewart), 29 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[1] Telegram from A. Gilchrist (Ambassador to Jakarta) to Foreign Office, 18 June 1965, FO 371/180366, The National Archives (TNA).

[2] Telegram from E. H. Peck (Foreign Office) to D. J. Cheke (Tokyo), 21 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[3] Most likely as a result of this introduction, Okubo was awarded four large reparation contracts (including the construction of the Indonesia Hall, or Wisma Indonesia, in Tokyo, or the expansion of the Indonesian Embassy in Tokyo), as well as the right to build several “prestige projects” of Sukarno’s, such as a guest house in the Presidential Palace and the iconic Monumen Nasional (“National Moment”) at the center of Merdeka Square in Jakarta. Masashi Nishihara, The Japanese and Sukarno’s Indonesia: Tokyo-Jakarta Relations, 1951-1966 (Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1976): 112-114.

[4] Telegram from E. H. Peck to D. J. Cheke, 21 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[5] As described in her own memoirs. Ratna Sari Dewi Sukarno, Devi Sukaruno Kaisōki: Eikō, Munen, Kaikon [The Memoirs of Dewi Sukarno: Glory, Regret, Remorse], edited by Aiko Kurasawa (Tokyo: Sōshisha, 2010): 35.

[6] Minutes by J. E. Cable, 24 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Comments by J. E. Cable to minutes by A. D. Malcolm, 22 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[9] Minutes by J. E. Cable, 24 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[10] Comments by J. E. Cable to minutes by A. D. Malcolm, 22 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[11] “Background note on Madame Ratna Sari Dewi Sukarno” in telegram from J. E. Cable to Mrs Stewart, 29 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[12] Telegram from E. H. Peck to A. Gilchrist, 15 July 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[13] According to the Foreign Office reconstruction, Gairdner had been working in Southeast Asia for several years and was at the time employed at a German company specialized in trading by Indonesia: “Madame Sukarno has been instrumental in helping them to a good deal of business.” “Note for the Record: Madame Sukarno’s Visit to London” by A. A. Golds, 29 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[14] ‘Note for the Record: Madame Sukarno’s Visit to London’ by A. A. Golds, 29 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[15] Telegram from A. Gilchrist to Foreign Office, 8 July 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[16] ‘Note for the Record: Madame Sukarno’s Visit to London’ by A. A. Golds, 29 June 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Letter from Suyoto Suryo-di-Puro to Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, 14 July 1965, FO 371/180366, TNA.