Sources for South and Southeast Asian History

Editor-at Large Dr. Kristie Patricia Flannery (Research Fellow at the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences at the Australian Catholic University) interviews Dr. Aditya Balasubramanian (Senior Lecturer in History at the Australian National University).

KF: This online history project responds to the “fragility, absence, or inaccessibility of archival materials” for the study of South and Southeast Asian history, and the multifaceted historical connections between these regions. Could you tell us about how you have encountered these archival challenges in your research, and what were the solutions that you found?

AB: My research so far has focused on India. File transfers from departments of the Government of India to the National Archives of India after independence in 1947 are erratic, and those from earlier periods can be poorly preserved or catalogued. My book project focused on the Swatantra Party, which did not have papers that became available until 2019, a year after I finished my PhD dissertation. Working around these challenges has meant mixing various different kinds of evidence and “reimagining the archive,” to take Sunil Amrith and Tim Harper’s turn of phrase from Sites of Asian Interaction. I, and many of my colleagues, take particular inspiration from the innovative work of Indonesia historian Rudolf Mrazek, whose Engineers of Happy Land involves working across multiple archives in the Netherlands and Indonesia and combining them with sources ranging from motorcyclist journals to poetry.

In my own work, I found the vibrant archive of print culture and untapped Government of India reports to be particularly valuable. I also turned to printed materials that can be read with a critical eye to illuminate things that they are perhaps not intended for, like short stories about prohibition to understand ideas about rural economic change. The book that has emerged, Toward a Free Economy: Swatantra and Opposition Politics in Democratic India (Princeton University Press, 2023), uses these alternative archives of South Asian economic life to explain how economic conservatism germinated in postcolonial Indian society and pluralized Indian democratic life. It offers a corrective to diffusionist histories of neoliberalism that assume the uptake of Western ideas in India by showing how it was actually local conditions and ideologies and selective appropriation of neoliberal rhetoric that shaped an Indian pro-market constituency.

KF: The “Research Blog” section of the website contains information about physical and online archives, and reflections about working with them by a range of scholars. What are some of the most interesting archival collections that scholars have worked with, and how have they been used to write new stories about the past?

AB: Insider knowledge about how to navigate an archive is exceptionally valuable. But there is no need for it to be inaccessible. Several excellent archives in South and Southeast Asia are a little bit difficult to navigate, and websites aren’t particularly helpful. Owing to that problem, I’ve assembled short primers on what they hold and the contact details for someone familiar with them. The majority of the items on our research blog are 27 guides to physical archival collections that provide a brief description of their holdings and the process for gaining access. We provide the contact information for the authors of these guides so that the interested researcher can get in touch with queries. Some of the collections are well known, like the Maharashtra State Archives. Others, like the Raghubir Library and Institute in Sitamau, Madhya Pradesh, are rather obscure. In this archive, for example, the interested scholar might find a plethora of documentation about the global opium trade in the 19th century, including the ledgers of opium traders from the Malwa region of central India. There are also rich descriptions of opium cultivation in the region.

The Research Blog further has ten “Research Experience” essays on how archival research has informed people’s studies of economic life in the region. Anthony Medrano’s essay shows how sources in the National Library of India have informed his study of malarial control in the interwar Netherlands East Indies which drew expertise and shared knowledge from across South and Southeast Asia. Julia Stephens writes about the human archive of memory and explores how an interview with a Sikh moneylender in Singapore illuminated her understanding of the economic life of South Asian migrants evolved intergenerationally in Southeast Asia.

KF: The Archives of Economic Life in South and Southeast Asia features an annotated Guide to Online Archives. The featured collections cover varied materials, from music and cinema to newspapers and government records across multiple countries and eras. Can you tell us more about some of the most fun/ interesting/ exciting collections?

AB: One of the most interesting collections is indiancine.ma, which is a catalogue and repository of South Asian cinema. It includes a catalogue of over 60,000 films that you can sort by various filters, including language, year, and themes. There is a combination of movie metadata, clips, and full movies. I have started to look at materials under one wonderfully specific subheading in my ongoing research on road transport!

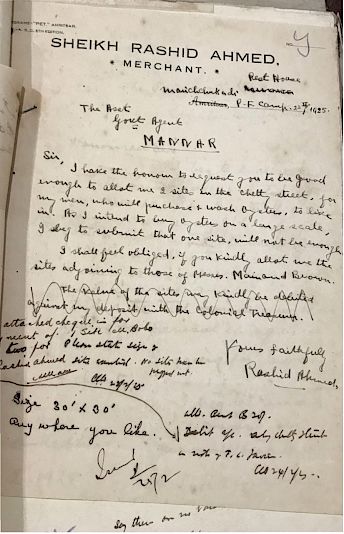

Another is called the Daily Journals of Batavia Castle, which has information about trade in what we today call Southeast Asia and with Europe during the 17th and 18th century. Batavia is now known as Jakarta (capital of today’s Indonesia). They offer a granular picture of incoming and outgoing letters, ships, and daily events in Batavia as the Dutch East India Company made inroads into the region and interacted with native rulers. Some of these records are images of handwritten manuscripts, and some are of printed documents.

KF: Looking ahead, how would you like the Archives of Economic Life in South and Southeast Asia to evolve? What have been the biggest challenges to building a functioning and impactful online history project?

AB: Our content focuses primarily on India. Going forward, I would hope to build our geographic coverage of South and Southeast Asia to less well-covered countries. I would also like to cultivate a more widespread network of contributors and engage archivists in this project. The biggest challenge is getting people to commit time and energy without many monetary resources. This has been a passion project that I do mainly in my spare time and a labor of the love of our many generous contributors.

KF: Who can get involved in and contribute to the Archives of Economic Life in South and Southeast Asia?

AB: Anyone! We are interested in content generators, possible interviewers, and pitches for multimedia projects. Please write to me at aditya.balasubramanian@anu.edu.au if you have any ideas.

Learn More about the Archives of Economic Life in South and Southeast Asia Project here.