Roundtable Panel—On Barak’s Powering Empire: How Coal Made the Middle East and Sparked Global Carbonization

The Toynbee Prize Foundation Presents

A Roundtable Panel Discussion on:

On Barak, Powering Empire How Coal Made the Middle East and Sparked Global Carbonization (University of California Press, 2020)

Discourses on energy and human life abound and run high in these times. Few days pass that we don’t read newspaper headlines or hear podcasts that talk of looming cold winters, rising electricity costs for the global poor, or economic price wars waged between behemoth fuel exporters. Oil—the carbon fossil fuel that is often thought of as the magical driver of modern life—is the epicenter of public reflections and contestations worldwide. This recalls, in ways, the early 1970s, which were dubbed the oil crisis years symbolized visually by empty highways in the industrial North. For many, this period cemented the connections between oil and great power politics. Today, the understanding of energy as the backbone of life is re-invented continually in public and scholarly discourses, with new characters and settings, against planetary urgencies, and alternatingly optimistic and fatalistic conclusions. In these narrations, however, history serves more as a backstage or feels like an off-the-limits crime scene rather than a living past that we carry on.

In response to this, reading Powering Empire feels like having a cold shower on hot, humid day. In contrast to a surrounding intellectual landscape often devoid of sharp, historical thinking, this monograph restores different historical subdisciplines to our thinking: physics and the human body, capitalism, oceans and waterways, and labor struggles. Powering Empire possesses many depths and layers of storytelling, with history and social theories rooted in places outside the traditionally-delimited West. This roundtable is evidence of the vibrant, diverse intellectual chemistries his work has spurred.

How can we re-conceptualize histories of energy, crucially necessary to understanding our times, and place them in longer, atypical timelines? We brought together scholars of different backgrounds and from different locations to begin thinking through this question on the heels of Powering Empire and to expand the prevailing conversation on the global history of energy more broadly.

— Rustam Khan, University of Hong Kong

Participant Bios

Arbella Bet-Shlimon is an associate professor of history at the University of Washington in Seattle. Her first book City of Black Gold centers on oil, urbanization, and ethnicity in Kirkuk (Iraq).

Shellen Wu is an associate professor of history at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. Her book Empires of Coal studies Qing and modern China’s entanglements with natural resources management, science, and technology.

Pascale Ghazaleh is chair and associate professor of history at the American University in Cairo. She has written extensively on labor, social history, and state-society relations in the 19thcentury Ottoman Empire.

On Barak is a professor of history at Tel Aviv University who specializes in social and cultural histories of science and technology in non-Western settings.

Reviewers' Comments

Shellen X. Wu, University of Tennessee at Knoxville

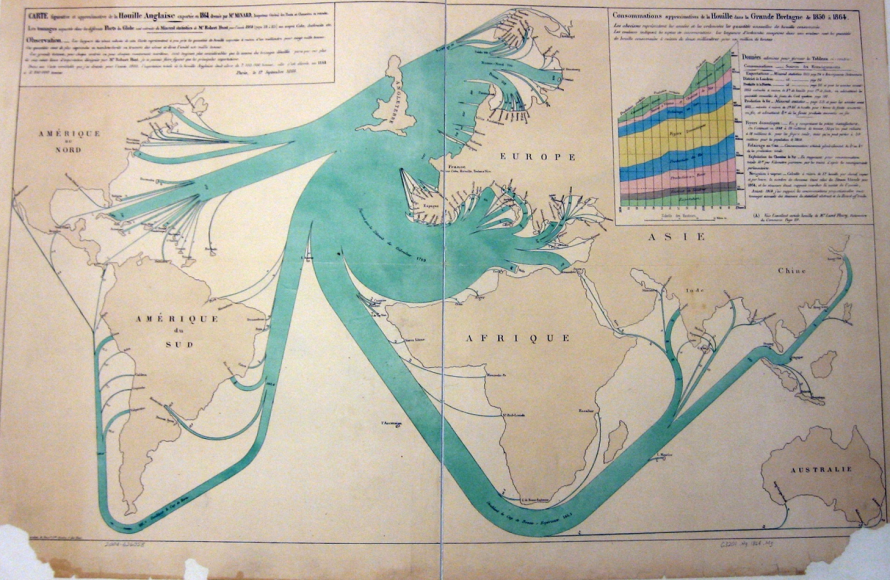

Images of the octopus bookend On Barak’s Powering Empire. The cephalopod, tentacles outstretched for maximal expanse, threads its way through the narrative, as well as serves as a model for the chapter structure of the book itself, with coal as the body of the many-limbed beast of the modern world. The cephalopod makes its first appearance in the introduction, a stylized map from Charles Joseph Minard’s 1864 work, British Coal Export, which illustrates the British coal economy in directional lines whose width represented volume. On the page the thick tendrils of coal take on an anthropomorphic life of their own. The map was described by contemporaries as a giant octopus, with one particularly thick tentacle nearly covering up the Straits of Gibraltar and the Mediterranean. The same map appears again later in the work, followed by a cartoon cephalopod that shows up near the end of the book (223). The cartoon, from the September 7, 1904 issue of Puck, illustrates coal/octopus as an inspiration and model for understanding the oil industry.

My imagination stirred by these multiple illustrations in Powering Empire, the cephalopod began to haunt my thoughts about empire, global connections, and the history of science and technology. Long after many of the other fascinating details revealed in the book (and there are many) faded in my memory, the octopus remained ever present, an expanding blob slowly covering up the world map. The octopus is not an animal normally associated with coal or, for that matter, energy. So, what is it about the this animal that so captures one’s attention?

As Barak points out, the image of an octopus is “a good metaphor for thinking empire, another creature whose tentacles are often smarter than its actual brain.” (9) More than its metaphorical appeal, however, in important ways the octopus and its tentacles make visible the structures of energy built by the British empire and which have since shaped the modern world and put into the motion the accelerating climate crisis of our age. Images of the multi-limbed beast of the deep ocean effectively counter the tendency in the historiography on the history of energy to make abstract and linear, through terms like “energy regimes” and “transitions,” processes that in sources and on the ground turn out to be far messier than historians have portrayed.

In the last decades, the history of energy has developed into its own ahistorical beast. The concept of energy, a child of the nineteenth century, was born of the same laws of thermodynamics that from its birth erased the historical context for how we understand energy. Broadcast as a universal constant since the beginning of time, energy appeared at once ubiquitous and ahistorical, having emerged from the beginning of time and then remained the same throughout ages, long before humanity’s appearance and presumably, long after our demise. No new energy is created. Energy merely dissipates and transforms in ways seemingly incompatible to history.

In one of the book’s most important contributions, then, is to give shape and history to this alleged transparent and all-encompassing entity, much as the octopus provided a tactile and visual shape to the influence of coal. For all its universal claims, histories of coal have had a surprisingly parochial concern with the English countryside, even as it provided the foundations for the dominance of the British Empire. As much attention as the British empire has received from historians, it has remained curiously absent in energy histories.

For all its universal claims, histories of coal have had a surprisingly parochial concern with the English countryside, even as it provided the foundations for the dominance of the British Empire.

In the traditional narrative, over the course of the nineteenth century fossil fuels replaced wood as the dominant form of energy used in human society. Contemporary observers noted the importance of coal to the vast economic transformations then taking place, as well as its less desirable environmental effects. Historians, economists, and other social scientists followed suit, from Max Weber and Werner Sombart at the start of the twentieth century to John Ulric Nef, Fred Cottrell, Edward Anthony Wrigley, and Rolf Peter Sieferle into the twenty-first. Sieferle studied coal’s cultural and economic significance by using the number of complaints about coal to track its use in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England. The nasty side-effects of burning coal aside, its use transformed labor, productivity, and the world in which we live.

Yet, for all its lasting effects and proximity to various explanations for the rise of British power, this story leaves out empire. Jürgen Osterhammel’s history of the nineteenth century described it as the “century of coal.” The overlap of the century of coal with the age of empire, as defined by Eric Hobsbawn, remains largely unexplored. Instead, the modern history of the nineteenth century is rendered as a succession of displacements and replacements. With industrialization, coal rapidly replaced the millennial dominance of wood, followed in the late nineteenth century by the use of coal-gas, and subsequently petroleum.

For Osterhammel, these changes in energy regime underlay the transformation of the modern world. Timothy Mitchell traced to the technological differences between coal and oil the foundations for the autocratic states in the Middle East. In connecting resource extraction and technology to political regimes, the idea of successive energy regimes also girds Mitchell’s arguments. The picture gets even fuzzier in other parts of the world from Asia to Latin America. The supposed universality of energy and science limited interest in studying how coal and the technologies for its use developed in specific places and environments away from Europe.

Enter the octopus. In placing the cephalopod front and center, Barak at once manages to center coal and empire while relocating the focus from the English countryside to the Middle East. Barak shows how coal enabled the extension of empire and amplified the effects of imperialism along the tentacles and connective tissues of empire, along Suez and the Gulf of Aden, much as the coalmines of north England. By demonstrating the multitude of ways that coal shaped the Middle East much as or more than oil in the twentieth century, Barak makes empire the front and center of the entangled history of how coal transformed the world and created the crisis of the Anthropocene.

With coal as the metaphorical head of the octopus, the tentacles spread into chapters on water, animals, humans, environment, and the insurance industry and its attendant calculations of risk. What comes out clearly is the way that coal, exported on waterways, combusted on steamships and rails, transformed the Middle East and in turn the world. This is a history of energy, embodied in a cephalopod, that restores history to a formless concept. I don’t know if the neologism Barak coined in the book, coalonialism, will take. But in making visible the connection between industrialization, technology, and imperialism, Barak has provided an important corrective to the historiography on energy.

Pascale Ghazaleh, American University in Cairo

Like On Time, Powering Empire is replete with vivid imagery (the octopus), surprising neologisms (coalonalism, coal-itions), and word play: Barak comments on an analysis of resistance to the introduction of condensers, “This reading holds water…” (p. 46). Barak, whose work is theoretically informed and empirically grounded, can afford a virtuoso’s flourishes, but these small humorous asides can convey the impression of a lack of seriousness—as though what interests him is more the flexing of intellectual muscle than the excavation of “the double historical nexus of how different energy sources are connected to one another and of the role of non-Western settings and actors in the global march of hydrocarbons.”

Thus, reading Powering Empire is in part about giving oneself over to unexpected lateral leaps, dialectical double-dips, processes often inseparable from the language in which Barak frames them. This is not to say that the processes he connects are fictitious—rather, that—as Flannery O’Connor said of fiction – “the meaning of a story has to be embodied in it, has to be made concrete in it. A story is a way to say something that can’t be said any other way, and it takes every word in the story to say what the meaning is. You tell a story because a statement would be inadequate. When anybody asks what a story is about, the only proper thing is to tell him to read the story.”

But can the same be said of a historian’s narrative? At times, Powering Empire seems to strain under the weight of fragile connections. This is for example the case in the section devoted to Gandhi and vegetarianism in the chapter on animals, which appears disconnected from the rest of Barak’s argument regarding the democratization of meat-eating. Why would “the politics of vegetarianism,” “a politics of passive resistance, of noncooperation, of avoiding rather than doing” (p. 65) be relevant enough to warrant development, whereas de facto exclusion from a carnivorous regimen for the majority of the population in the areas Barak discusses does not seem to be? It would make as much or as little sense to analyze Sheikh Imam’s famous 1960s song, about a news item in which a certain Dr. Mohsen touted the alleged health benefits of fava beans (to which the sheikh responded “let us die by meat / while you live and eat beans”), in light of vegetarianism as a political stance.

Bringing superficially unrelated incidents or processes into conversation with each other to reveal hidden connections is a powerful tool in a historian’s arsenal, but sometimes unrelated incidents are just that, and the creation of connections through language falls flat—or obfuscates larger, more important or causally more powerful processes. Viewing events through the wide lens of “interspecies [or] intraspecies predation” allows us to see how the meat industry changed ecology, but detracts from the racism of the regulations that “prevented Egyptians from using firearms to shoot birds from their boats, whereas non-Egyptians were exempt from this restriction.” (p. 66) In a similar way, the section on “coalonial” bodily comportments gestures towards “convergences,” but these are not made explicit; the section’s conclusion suggests only that viewing the Middle East from the East, “through the perspective of coal and meat[,] reveals quite another history” than that read from the oil-centered perspective of the West. What is that history? Simply one in which Gandhi and al-Qa`ida are juxtaposed? In which the inscription of politics on the individual body through asceticism and suicide represents a “convergence”? This seems too close for comfort to the “culture of martyrdom” school of Orientalism, and therefore merits further elaboration.

Powering Empire, therefore, has led me to reflect deeply on questions of synchronicity and causality—and if that were its only contribution to current historiography, it would be considerable. That is not the case, however. To my mind, chapter 3 is the heart of the book; it contrasts with the previous chapters in its clarity and ability to trace complex dynamics and reveal connections requiring no rhetorical embellishment. It opens with a persuasive discussion of the abstraction of labor and its discursive transformation into pure physical energy, includes a cogent analysis of the abolition of slavery and its effect on coolie labor, and ends with a profound reflection on the multiple interactions of pain, skin color, and energy expenditure. Barak deals a death blow to the argument iterated by e.g. Beinin and Lockman, as well as Gorman, according to which worker activism was imported to the Ottoman Empire by Greek and Italian laborers in the tobacco industry and dock works.

Labor historians have attributed the alleged passivity of workers native to the Ottoman lands to the comparatively small size of the industrial working class, the state’s intervention in the economy, the supposed absence of an indigenous capitalist class, traditions of quietism, and a number of other causes. Barak, in contrast, shows clearly how local labor activism—most commonly deployed in petitions and strikes in addition to withholding taxes and sabotaging transport and communication networks—was suppressed by a combination of European and Ottoman state pressure. In particular, this pressure involved drawing on the systemic universalism created by coal mining and transportation in some circumstances (breaking strikes by replacing recalcitrant workers with refugees or emancipated slaves) while suppressing universalism in others (attempts to address the colonial state in terms that emphasized the rights demanded by workers everywhere). These rights, granted to British subjects on whose white bodies the pain of working with coal was legible to the British ruling class, were refused to brown colonized peoples under the pretext that they had different abilities and a far higher tolerance for inhuman working conditions. The Ottoman state collaborated with European governments and corporations to break labor unrest; and, just as some segments of the Ottoman working classes were being stripped of ties to the land and becoming fully proletarianized through their reliance on wages from coaling, Britain’s shift to oil deprived them of strategic leverage.

This chapter concludes on a haunting note: “there seem to have been foreign ghostly bodies whose transparent life-blood nourished global capitalism. In part, the success of the more familiar specters haunting Europe depended on the invisibility of these bodies.” (p. 114) And workers across Europe, who fought for the right to vote as a way of countering the worst excesses of capitalist bosses, contributed to the tailoring of democracy to “one kind of body politic.”

Arbella Bet-Shlimon, University of Washington in Seattle

In Powering Empire, On Barak urges energy scholars who associate the Middle East with oil, and non-energy scholars who may not think fossil fuels are relevant to their work, to rethink the origins of carbonization, the Middle East’s relationship with that process, and the concept of energy transitions. Coal, in other words, was not made obsolete by oil—rather, carbonization, in longer view, emerges as a continuum with a complex of social, political, material, and embodied effects. Barak’s history of coal, the infrastructure of the British Empire, and the making of the “Middle East” (a colonial concept) helped me, as a historian of oil, identify certain presumptions underlying how we write the history of fossil fuels.

My first realization was that, even when we try to avoid the pitfall of environmental determinism, historians of fossil fuels have too often leaned on the accidental nature of the areas where coal and oil are found as a component in analysis. In Southwest Asia and the Asian-African nexus, the movement of tectonic plates millions of years ago, long before human life existed, created a series of oil and gas deposits. As I have written in my own work, one of the larger ones happened to be located under what would become Kirkuk, now one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities. Others clustered densely around the Persian Gulf coastline. The people who came to live above the prehistoric fields of decomposed plankton had their lives shaped by them wherever those fields were extracted. These points are certainly true, but Barak’s work calls into question how much significance we have assigned to their unpredictability. Indeed, economic historians’ much-critiqued theories of the “great divergence”— Europe’s rapid economic growth through industrialization and Britain’s decisive imperial advantage over other powers starting in the eighteenth century—often attribute these phenomena, as Barak notes, to the fortuitous location of British coal and its proximity to water.

But because he locates the initial process of carbonization in the Middle East in the heyday of coal, not oil, Barak does not see carbonization’s trajectory as a product of geological coincidence. By focusing on the movements and distant uses of fossil fuels rather than their points of origin, Barak shows that the Middle East’s role in carbonization is a deliberate outcome of British imperial expansion. Although the region eventually did develop its own coal industry, its infrastructure, technologies, and consumer products were largely transformed by the shipping of coal mined elsewhere (particularly in Britain). Barak’s approach suggests possible methods for historians of oil in the Middle East, too—for instance, future histories could pay closer attention to oil’s pipeline networks and downstream industries, like petrochemical consumer products. Historians might also more explicitly consider why oil fields in certain places are exploited before others, or extracted in ways that others are not. All of these questions tie, in one way or another, into the ultimate downstream effect of climate change—a central concern of Powering Empire.

But because he locates the initial process of carbonization in the Middle East in the heyday of coal, not oil, Barak does not see carbonization’s trajectory as a product of geological coincidence. By focusing on the movements and distant uses of fossil fuels rather than their points of origin, Barak shows that the Middle East’s role in carbonization is a deliberate outcome of British imperial expansion. Although the region eventually did develop its own coal industry, its infrastructure, technologies, and consumer products were largely transformed by the shipping of coal mined elsewhere (particularly in Britain). Barak’s approach suggests possible methods for historians of oil in the Middle East, too—for instance, future histories could pay closer attention to oil’s pipeline networks and downstream industries, like petrochemical consumer products.

Centering coal and shipping also de-exceptionalizes the Persian Gulf in the history of carbonization. The core of Barak’s book is in Egypt, Aden, and the Red Sea. The peripheries of the book are in a multicontinental network of ports that became an archipelago of distinct legal regimes and cultural practices, affecting the lives of migrants and locals well outside the fossil-fuel industry. Reading Powering Empire at times feels like boarding a series of ships. Each one ends at a different destination from where it started, often somewhere that the reader does not expect. This is not a fault of the writing: Barak carefully outlines his main points as the text proceeds, but it can still go in fascinatingly unexpected directions.

The effects of coal unfold from page to page, like ports on a shipping route. For example: the movement of coal by sea transformed shipbuilding, which required the building of modern ports, affected the usage of ballast in ships (because of its weight), and enabled salt production at coaling stations (the salt, in turn, also served a ballasting function). And: the network of depots in coal’s maritime infrastructure required the widespread building of lighthouses, which led to the lighthouse becoming a motif in Islamic reformism. In another discursive change, the mining of fossil fuels in the Ottoman Empire created a need for translating geological knowledge, which shaped new ideas about the value of land (and what was under it) at a moment when the empire was adopting new concepts of land tenure. To follow these routes of coal’s influence, Barak synthesizes a vast array of historical research, often well outside the field of energy history, with contemporary published and archival sources. The sheer range of observations pointed in different directions means that, at times, Barak stakes a bold claim about the tertiary effects of coal, several links down a cause-and-effect chain, that cannot be fully established in the space available. Nevertheless, this method is a welcome departure (in more ways than one) from histories of fossil fuels focused mainly on the site of extraction and politics of the country that site is located in.

Barak’s ultimate concern, brought to the fore in the book’s conclusion, is the climate crisis caused by carbonization—an “entanglement of energy and empire.” This final essay, brief but as ever wide-ranging, proposes future directions for personal and collective action to mitigate the crisis, notably degrowth, as well as encouraging links between the energy humanities and Islamic studies. Given the book’s consistent clarity throughout each chapter about the deliberateness of imperial carbonization, it is perhaps unexpected that the world’s largest empire and the country responsible for the largest cumulative carbon emissions—the United States—is not mentioned specifically. But Powering Empire provides a lot of provocative material for thinking through what “anti-coalonial” politics might look like for scholars in the imperial core.

Author Response by On Barak, Tel Aviv University

I would like to begin by thanking the Toynbee Foundation for hosting a roundtable on Powering Empire, Rustam Khan for organizing it, and the reviewers for reflecting on the book from the perspective of three different historical subfields. I wish to use this rather rare opportunity for a written exchange with one’s reviewers not to reassert authorial intent—books belong to their readers—but rather to evaluate how the book’s arguments hold water considering these readings and in new contexts since its publication.

As all reviewers have noticed, the elephant in the room is climate change and the question of how and from where to approach it. Anthropogenic environmental degradation is repeatedly exacerbating the already pressing urgency characterizing discussions of fossil fuels. Yet with all the talk about global decarbonization as the most important mitigation measure for climate collapse, when I approached the subject we lacked a historical account of global carbonization—an explanation of how the hydrocarbon economy spread worldwide to become a key facet of our current technosphere and geopolitics. Taking on this task, Powering Empire adopted a distinctive notion of globality—not the methodological planetarism of climate science and its “Anthropocene” or “global warming” that are everywhere and therefore nowhere in particular. Instead, the book focuses on a distinct corridor—between Aden and Port Said—that was a tail waggling a larger dog or to use a more apt metaphor, one tentacle in a loosely integrated imperial system of maritime fueling stations that contemporaries likened to a giant octopus.

Shellen X. Wu reflects on this tentacular logic in the opening of her review. Beyond her incisive answers to the question “why an octopus?” for me this is also a device to stress the oceanic and coastal nature of the story of fossil fuels—a story that is usually seen as terrestrial, especially when dealing with coal, which unlike oil was wrongly thought not to have crossed seas. Alongside this horizontal aquatic logic, the octopus also helps tease out the importance of verticality: not only of the underground from where fossil fuels are extracted or the atmosphere where greenhouse gases emanating from their combustion are deposited but again mainly at sea—on the water’s surface as well as underneath. My focus on aquatic verticality reveals aspects of coal usually left under the radar, like its weight, which allowed coal to serve as ballast before it became an energy source. For example, keeping ships bottom-heavy, coal was essential for the development of a return-trade in the British Empire. Finally, the octopus’s tentacles also help draw attention to the importance of corridors—narrow natural and increasingly artificial waterways that channel maritime mobility—and to the importance of their depth and width. About a year after the publication of Powering Empire, the Suez Canal was clogged for days by a super containership in a way reminiscent of the steamships hitting the canal’s banks during the nineteenth century. In this and many other respects, the book shows and the present concurs that we are still trapped in coal’s ember and in a very long nineteenth century.

Wu situates Powering Empire also in the history of energy and thermodynamics, and identifies a crucial argument that recent years have thrown into sharper relief. As I started noticing after the book was published, fossil fuel companies increasingly rebrand themselves as “energy companies,” invest in renewable powers and promote “energy transitions,” while maintaining and even intensifying their extractive impetus. These slights of hand are enabled by the abstraction of energy that allows one to translate heat, motion, and work, as well as coal, oil, and solar power into one another, obfuscating their specific materiality in the process. Energy and thermodynamics are undoubtedly crucial to making sense of the world. Yet these optics come at a price of directing attention away from other key facets of objects such as coal. Three strategies are available to a historian interested in critiquing this process of obfuscation: to historicize the science of energy, thereby revealing its contingencies and roads not taken; to flesh out its political aspects, for example its entanglement with the imperial project; and to attend to what this science ignores – such as the materiality of coal. In Powering Empire, I combine all these strategies. Wu hints at this combination when she astutely situates my book in the historiography on coal as filling a crucial lacuna on its imperial aspects. While the long nineteenth century was famously understood as either the age of empire or as the age of steam, Powering Empire is indeed the first book to seriously probe the convergence of the two.

Wu ends her review wondering if “coalonialism”—the neologism I coined to capture this nexus of energy and empire—will catch. My guess is as good her hers. Yet alongside its questionable catchiness there might be other reasons to endorse it. Like the hyper-object of climate change that requires rethinking time, history, and causality, carbonization too invites a certain elasticity and a new esthetics. Father of the octopus, Charles Joseph Minar, discovered this when creating a new visual form for data communication. Coal was “too important to notice”: present anywhere from science and technology through urbanization, diet, and agriculture, to theology and art. This fact invites a narratology and idiom for telling a story that connects domains seemingly remote from one another. Such connective leaps and tissues may be exhilarating, but also disorientating and frustrating.

These considerations hopefully speak also to Pascale Ghazaleh’s displeasure with the book’s writing style. To the extent one can be explicit about such things, my writing seeks to draw attention to how language itself, scientific and quotidian alike, was reshaped by coal-fired technologies (that allowed, for example, telegraphing words across vast distances) and the imperial purposes to which they were put. In fact, even if neologisms and metaphors are rightly frowned upon, sometimes their very awkwardness serves an important purpose of denaturing language, especially English. I sometimes feel that my non-native-speaker stance towards this language gives me license to demonstrate in idiom my call to recycle and repurpose existing imperial legacies and apparatuses.

Ghazaleh, the social historian, finds my intervention in that field (this is Chapter Three, titled “Humans”) and in labor history as the heart of the book. I am happy and proud that a prominent social historian approves of the section that is closest to her expertise. Yet my choice of an octopus to visualize the argument’s form was meant to suggest that this is not a text with one heart or a single core, certainly not a human one. Reading humans as part of a broader ecology, I was trying to show, does not necessarily entail abandoning the old Marxian materialism and political economy. Indeed, part of the book’s intervention is to wed old and new materialisms. At the same time, existing formulae must be repurposed. For example, the central position and purchase of categories such as “race” is inflected when discussed as part of an intra- and interspecies dynamics of predation as I show for what I understand as the multi-species boomtown of Port Said.

Ghazaleh finds other parts of the book, such as the discussion of diet, unrelated directly to the main discussion of coal. I beg to differ: with all my fondness to metaphors, examining coal’s role in the proliferation and expansion of a carnivorous diet is probably the best way to demonstrate how coal addiction was a very literal and physical thing. In this process, the human body was reconceived as a fuel-burning motor akin to a steam engine and new coal-fired technologies of refrigeration and transportation democratized meat consumption. In this context, Ghazaleh critiques my call for a return to early-twentieth-century Egyptian Islamist engagements with Gandhian vegetarianism, suggesting that this kind of politics is an iteration of elite admonitions. Yet the famous Shaykh Imam song she marshals to this cause, and which Egyptian intellectuals sometimes cite when seeking to criticize rebukes about carnivority coming from international climate science elites, in fact helps illustrate the inadequacy of this critique. The smart and funny lyrics were written by poet Ahmad Fuad Nagm probably in 1973 gaining popularity (and the regime’s ire) during the 1977 “bread riots” or “IMF riots” after the International Monetary Fund tried to impose structural adjustments that entailed canceling bread subsidies in Egypt. The song was a sharp response to the duplicitous meat-eating international and local elites on behalf of most poor Egyptians whose basic vegetative sources of protein and carbohydrate were coming under severe attack. So, if this song demonstrates that taste for meat was already rife among the Egyptian lower classes by the 1970s (a proclivity that I show to be only a century old at that point and related to coal-fired refrigeration), it was part of an effort to defend quite a different diet. More generally, instead of supporting paths to social mobility that entail climbing on the corpses of other creatures and the planet itself just because they can be grounded in a popular and supposedly authentic foundations, Powering Empire demonstrates that this foundation is itself rather new and shaky, and that other historical genealogies are available.

Arbella Bet-Shlimon’s take represents another key perspective with which Powering Empire engages, sometimes explicitly but more often implicitly—that of oil experts—and her insights throw into sharper relief how fruitful this conversation can be. To begin with, what she identifies as the “pitfall of environmental determinism” that Powering Empire might help bypass actually represents a step forward for a field that long addressed oil mainly through the optic of Petro-dollars, while ignoring the materiality and geological/environmental embeddedness of this fossil fuel. Such materiality is crucial yet, I agree with Bet-Shlimon, also insufficient. At stake is not only environmental determinism or the prehistoric roulette game that distributed different resources in different undergrounds. Riding on it is the proper place of materiality in general. If oil seems to spring independently from the desert sands, propelled only by the gases trapped beneath it, in fact its extraction and use stand of the shoulders of an older fossil fuel, coming from outside the region an entire century earlier, initially in the service of an imperialist agenda. Stressing this fact has political implications: in crucial respects, the legacies and path dependencies of nineteenth-century coal import created the Middle East we know today. Without grasping them we cannot adequately understand the region, oil extraction, or climate change. Especially in a region nowadays mainly associated with oil, rapid overheating in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries (in some settings more than double the average global warming standards along with the desertification, droughts, and attendant geopolitical tensions) may seem like poetic justice, where the burning oil economies are being duly punished for their oil extraction policies. A longer history of fossil fuels troubles this neat morality tale and helps expand the list of wrongdoers (without letting oil producers off the hook).

Bet-Shlimon’s review is the one most oriented towards the present (of oil) and the present-future (of climate change), suggesting that some of the insights and analytical protocols I apply to coal may work also for oil and maybe other resources as well. Unsurprisingly perhaps, the best example I can think of for the veracity of her statement is the work of my PhD student Shira Pinhas on oil in Mandatory Palestine, where she examines oil downstream from Kirkuk. Yet Bet-Shlimon’s insight also points towards a more general direction: of the need for energy humanities. Coal and oil surely have significant material differences. One is solid, the other liquid, one labor intensive the other technology and capital intensive, for example. But the human history that connects these two forms of carbon as fossil fuels or energy sources and which offers a base for comparison that reveals such differences as well as similarities, must be part of the analytical wherewithal with which we approach both.

Bet-Shlimon ends her review wondering about the absence of a direct reference to the United States in my book. As far as teasing out the continuities of empire, this query is justified. Yet an important facet of my argument against the notion of “energy transitions” as the key organizing principle for mitigating climate change is that in many respects we are still trapped in the age of coal. Indeed, 2021 was a record year for coal combustion and for the resulting global greenhouse gas emissions. The US, where reliance on coal is on the decline, is not a good example of this trend, unlike China or India. Stressing historical connections with the latter settings allows tying the Middle East to South and Southeast Asia rather than placing it only on the familiar East-West axis. As recent years have again thrown into sharper relief, the centrality of the US in exacerbating climate change and especially its role in mitigating it was significantly diminished.