Finding Law in the History of Global Violence: An Interview with Lauren Benton

Violence is, in the public imagination, the law’s radical Other. Brutality and cruelty, we tend to believe, are elements that flourish in law’s absence. Not only is the appearance of violence a symptom of the absence of order, but its bloody outbursts are taken to be utterly meaningless. The narrative of the emergence of “modern” law —both within, and beyond, the nation-state— is usually that of the triumph of reason and deliberation over violence. This progression supposedly entailed the prohibition (or at least, the domestication) of force in local and global politics. Against this rather rosy narrative, Lauren Benton invites us to read the ways in which violence and law act, together, to cement claims of global order.

Benton does so by placing so-called “small wars” at “the center of a new history” of interpolity relations (p. xii). Instead of seeing them as mere “manifestations of insurgency and counterinsurgency,” she studies how a variety of practices (“raiding and other sporadic violence as well as conflicts that were small in scale, remained undeclared, or lasted for relatively brief periods”) were central to how European empires justified the legality of their expansion over the globe (p. 7). Such “small” wars, in fact, could be quite “big” in scale or “long” over time. What matters is that all these instances of violence oscillated at the “threshold of war and peace” (p. 8) —and, as such, raised thorny questions about their legal basis all long the imperial chain of command. The productive ambiguities offered by this “law of neither war nor peace” offered enormous opportunities for those who knew who to exploit them —as Benton shows by tracing how imperial agents negotiated this threshold at different times and places, from the Iberian Conquistadores “discovering” the Americas all the way to their successors in our own day and age (p. 184-185).

The contours of this vague threshold were not, as Benton argues, predetermined by the metropolitan laws of expanding European empires. Pushing against histories of “diffusion” of laws of war from the West to the Rest (p. 9), Benton instead analyzes how agents in different imperial locales —for instance, in both the colonial frontier and heartland— raised arguments about the legality of violence within and beyond the threshold (p. 60). Moreover, “not just Europeans, and not just law-trained elites” were productively exploiting the ambiguities of this threshold (p. 17). The book is replete with cases in which non-lawyers (for example, a British captain patrolling distant seas) or local elites (for instance, rulers in South Asia) were active interpreters of the law applicable to the violence they encountered (p. 146). By bringing together a variety of materials from different continents and periods, Benton provides a thoroughly global account of the interpenetration of law and violence in the making of empire —past, present, and perhaps even future.

-Daniel R. Quiroga-Villamarín

Daniel R. Quiroga-Villamarín (DRQV): Let me start on a funny or silly note. Over the last months, in certain social media platforms, a new trend has emerged. Apparently, in the wake of a question posed at some point last year by a hashtag, people are now using the expression “My Roman Empire” to make reference to things they think about a lot. Regardless of whether it is true or not that most heterosexual men think more often of Rome than they should, it does seem that this particular constellation has a particularly enduring imaginary of what an “empire” is. One thinks, if at all, of legions of soldiers in orderly formation. We tend to foreground, in other words, the massive campaigns in which “Roman forces aimed at complete dominance and annexation” (p. 32).

But your book shows that this is a rather misguided image of how empires in general —and the Roman one, in particular— engaged in practices of expansion. Instead of the campaigns of massive armies, you foreground “small” wars marked by practices of raiding. Indeed, in your account, the rise of empires does not follow a given path predestined by the might of metropolitan power, but is rather taken —a settler, military officer, or conquistador at a time— step by step, in a piecemeal and improvised fashion. How does your focus on violence at “threshold of war and peace” help us rethink imperial history in ways we would not grasp if we only focused on “war proper”?

Lauren Benton (LB): Thanks for the question. And for the conversation. You've put your finger on exactly the impulse behind the writing of this book. It started in the way that I like to start these projects: that is, with a big, open-ended question in response to something I was observing in the global history literature that didn't feel quite right. In this case, it was the emphasis on major wars in the global history of violence. That’s true both for the histories of the twentieth century and for what an earlier “Age of Empires.” The historiography highlights the major conflicts: in the earlier period, it’s the Seven Years’ War (which some people call the first truly global war), the Atlantic Revolutions, and the Napoleonic Wars; in the later period, it’s of course the two World Wars.

But we all know from reading the history of empires that there they are chock-full of smaller episodes of violence. And so, I began with just that open-ended question: can we discern patterns in these episodes of “smaller” violence? And, because I am interested in legal structing and legal history, I wanted to examine the legal justifications for this violence. In other words, what was the legal framework for these recurring episodes of small violence? Small, but serial, violence, I must add. Because that's the other thing that we know from reading the history of empires: they were riddled by series of what are sometimes labelled discretely as “small wars”—and by actions that aren't called war at all but are clearly there —like raids or punitive expeditions. So that was the question the oriented the project from the beginning.

The answer to that question was that, indeed, there are clear patterns. And, moreover, we can think of them as legal patterns, and they are also global patterns. The result is a different view of empires as partly organized around these patterns of violence. And also a different view of global ordering.

DRQV: This point about patterns of global practices neatly transitions us to my next question. Something that connects this book to your previous scholarship is the insistence on a shared repertoire of legal practices across the early modern inter- and intra-imperial worlds. This is what you call “interpolity law” or “big law” —to refer to a rather broad shared understanding of legal questions related to jurisdiction, protection, and punishment (p. 12-13). How are we to make sense of this law —and of the fact that it appears to be shared even across vast cultural and geographic divides?

LB: That's a great question. And it's something that has interested me for some time. As you say, I've been working with this concept of “interpolity law” to try to understand the ways in which law was organizing interpolitical relations before we can begin to identify something like “international law.” I think of interpolity law as an international law before international law.

It is very striking that polities of various scales came into interactions with one another with certain kinds of categories of legal action that were at hand and that were ready to be deployed in those interactions. And so, when polities encountered each other, they were looking for markers of legal authority —they wanted to know whom they could pact with. They understood that there were also markers of jurisdiction, protection, and punishment. And they found a shared approach to jurisdictional politics. Discourses and arrangements of protection between polities were also very common across the board.

Now, sometimes people say to me, “Well, is this an argument about universal qualities of law.” But I don't see it that way. Instead, I try to look at the way that the practices —the legal practices in interactions— were themselves producing legal structures across polities and regions. This was true even across inter-political regions, and indeed —in the early modern world— across the globe. So, it's not an emphasis so much on shared understanding as it is on the striking mutual intelligibility about legal practices in the early modern world.

DRQV: You really make this point by showing that Europeans and non-Europeans also found mutual intelligibility in certain practices in the conquest of the Americas. And this goes against narratives that see instead an encounter in which patterns of violence —buttressed in the framework of this interpolity law— were taken to be utterly devoid of meaning. This also allows me to me to then turn to the third question I wanted to ask you. Perhaps we can talk a bit more about method before we turn to substance. Your argument pivots on a survey of “exemplary conflicts in overseas European empires between 1400 and 1900 to reveal broad patterns” (p. 9). Could you tell us more about you chose the regions, periods, and dynamics you place in conversation?

LB: I would like to be able to say that my choice of case studies responded to a well-thought-out plan at the beginning of my research—but it didn’t. As I said before, I started out with an open-ended question, and I just started reading a combination of secondary and primary sources. As one is doing that, one of course starts taking decisions about cases. One is looking for places to dig deeper and really get to the micro analysis of these interactions. And so, a lot of the case study selection was serendipitous. That is to say, I was reading, I was looking for interesting cases that lit up the questions I was asking—and that connected to archives accessible to me and where I could read the languages (two essential conditions).

Now, it did occur to me early on that I wanted to bring in some regions that typically are sidelined from global histories. A number of the case studies are drawn from Pacific history. The legal history of the Pacific world has been booming, but my sense is that it has not been well integrated yet into broader global history narratives. And for a variety of reasons, the legal history of Latin America has also not been well integrated into global history narratives. Accordingly, I have a number of case studies from those regions in the book.

I also looked for a good chronological array. There was a moment when I realized I really needed to focus on some of the small wars in the mid-eighteenth century, because that period was a turning point towards a much more muscular European claim of authority over the laws of war. I wanted to locate the shift towards that claim if I could in small mid-eighteenth century wars in colonial settings —and it turns out that, indeed, there was lots of evidence for that. I chose two cases that had plenty of documentation available. The other thing I will say about my choice of cases is that I like taking them from different parts of the world and putting them side by side. In a number of chapters I juxtaposed cases with forethought, so I could break down some of the assumptions about regional differences or differences between “settler colonies” and other kinds of imperial formations.

DRQV: I agree that it is very important to think of these places in conversation! I really enjoyed, for instance, how your work on what is now the borderlands between Uruguay and Brazil help us think of other places and other sorts of patterns of violence. And I do have a question about eighteenth century militarization that I will ask you a bit later. But before, let’s first unpack the core of your argument. I was recently reminded of Frederic Jameson’s quip that “all politics is about real estate […] essentially a matter of land grabs, on a local as well as a global scale” (An American Utopia, p. 13). Perhaps! But as I read your book, I thought that perhaps we ought to add booty and even literally people to the list. For your monograph reminds us that raiding and captive-taking were central to European imperial expansion. In this way, your book offers challenges the traditional historiography of slavery and empire. How does your book help us rethink the relationship of law to “systems of enslavement and organized plunder”? (p. 17).

LB: This, to me, was one of the big payoffs of the research. It allowed me to begin to be able to think about both these “land grabs,” as you're labelling them, and about colonization in general as phenomena that involved serial violence from very early stages. In fact, one of the things that you see when you look at the history of imperial expansion is that the annexation of land usually follows a long period of raiding. And raiding has its own legal logic. It has its own forms of truce making, about which we will talk more in a minute, I hope. It has its own sorts of justifications, and its own connections to domestic law. It turns out that raiding (for both booty and captives) was a ubiquitous and elemental process in empire-making.

And then, raiding is paired with transitions to annexation and to the creation of more expansive imperial holdings. In one chapter of the book, I focus on the way that practices of land holding are closely paired with practices of legalized enslavement in early empires. They proceeded together. I discuss the examples of the Portuguese Empire in the Indian Ocean and of the English in Jamaica to trace the processes that turned military garrisons into settler colonies. That transition hinged on the ability of empires to create households that were able to hold captives and convert booty into property. Households played a central role in imperial formation. There are two points that are key to emphasize: raiding was ubiquitous across the early modern world (as was captive-taking). And empires depended on processes that connected this culture of raiding to practices of colonization and linked captive-taking to the building of institutions —including institutions and practices of enslavement on a grand scale.

DRQV: I think that is very important because we often think of raiding as a distinctively non-European practice. But you note that it was really at the center of European projects of imperial expansion. And, in that sense, I wanted to zoom in with regards to what you already mentioned about households. This leads us to the role of non-state agents in the expansion of empire. For instance, I really enjoyed your chapter on the role of households (nominally “private” or “civil” institutions) in the consolidation of imperial expansion (p. 75 & ss). And again, this pushes against this focus on “big wars” waged by “public” soldiers directed from the “metropole.” Can you tell us more about how non-official actors —and especially, settlers— engaged with this threshold of violence to justify imperial action (or inaction)?

LB: Well, you know, early modern historians are usually quick to say that in the early modern world, the lines between the private and public were very blurred. But I thought it was important to try to get past that insight—or to deepen it. That required analyzing the actual dynamics that were making —and crossing— a porous private/public divide.

There was a distinction between private and public. And yet, there were also processes that combined the private and the public. I probe the relationship in the chapter you allude to about households. We have a lot of literature about households as social and cultural institutions and as places of conflict over gender, race, and rights, and for tensions about enslavement, service, and even parent-children relations. But I couldn't find very much on the relationship between households and war. And yet, in these early empires, households were truly essential as quasi-private, quasi-public spaces of war. We can think of them, in a way, as paradigmatic private spaces for public warmaking—and for the justification of war.

This happened in a couple of ways. On one level, there was an imagination of households as entities that were actually continuing the punishment of war captives. They were supposedly doling out mercy —the idea was that the enslaved war captives were being spared from death. Households were very much part of the war-making apparatus in that sense.

And households supported war on another level that I found very striking. This insight came straight out of the sources. It wasn't something that I began to think about initially. Imperial agents started to argue that they had the right to wage war locally—without referring back to the metropole for authorization—because they had to protect communities of households. Correspondence was flowing back to metropolitan centers about the right to make war, and at the same time local colonial households were claiming that they had the right to engage in violent practices —including private raiding—mainly on the basis of self-defense.

This very expansive argument about self-defense was closely related to the imagination of these distant places as political communities. In the book I also bring out the strand of scholastic thought that placed households at the heart of political communities. The focus on households shows us something new about violence in early European empires. And as I point out in the Jamaica case, highlighting justifications for waging local wars allows us to reinterpret the role of pirates and piracy in war-making.

DRQV: Something I found very refreshing of the book is that it dispels this narrative in which legal ideas are something that happen solely in Europe and then slowly diffuse until they reach the margins of empire. There are plenty of stories like these about, for instance, the laws of war. In a way you show that different places at the same time are posing similar questions regarding law or violence —for instance, what you just said about self-defense. In in many cases, the metropolis did not have the lead. In fact, your book shows that early European imperial might was less overwhelming that its supporters and critics might have credited it to be. What we see in your book, instead, are European military structures riddled by anxieties about the fragility of their colonies, that sometimes even get caught up in the struggles of local rulers. How does your work help us rethink this “metropolis to frontier” sort of narrative?

LB: Well, that is one of the central themes of the book. And it flows from a methodological choice that I made while I was writing. I did not want to write a book that was entirely about legal practices and justifications for violence that were happening out in empire far from Europe. But at the same, I didn’t want to do what we’ve been struggling with as a discipline for some time now. And that is to attempt to trace flows of information from metropoles to frontiers or peripheries and back again, in order to gauge influence. I thought: what if I just dispel with that question entirely? I’m not interested in the flow of information per se. I just want to view how legal practices and arguments were developing about violence in the empire, and then take that as a lens through which to look at some European theorists and writers and ask whether I see them in a slightly different light. The point is to imagine parallel spheres in which similar legal problems were being discussed. And for me, that approach was very generative. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t think there is anything wrong with work that traces vectors of influence—in fact, I’ve learned a lot from that literature. But I found it to be enormously stimulating to just think about metropoles and colonies as different arenas for the production of both legal theory and practice.

DRQV: With this in mind, I now wanted to turn to one of the specific legal practices that you already mentioned. At the threshold of war and peace lies the ambiguous —and in your view, tragic– institution of the truce (p. 60). Could you talk more about the ways in which imperial authorities exploited the unclear meanings of these pauses in fighting (which could be read both as recognizing the equality of belligerents or a reduction of one of the parties into vassalage, depending on whom you ask)?

LB: I did find truces to be both tragic and interesting to focus on. In fact, I would say that if there was one “aha!” moment working on the book initially, it was when a I read a slim, relatively obscure volume by a Spanish historian, in which she assembled the truces that were made between the Catholic Monarchs and the rulers of Granada in the 150 years or so prior to the conquest of Granada. That was the moment I thought, truces are truly the motor of conquest. I could then look for truces in other settings where empires were on the move.

The Granada example is mind boggling. There were an astonishing 74 truces in the century and a half before the conquest of Granada—one after another after another. Most of them were broken before they were set to expire. And as you point out, they were not equal peace pacts —they were actually expressions of inequality of power. The Granada rulers said that they were “vassals” of the Christian Catholic Monarchs and agreed to pay tribute. And these momentary halts to fighting always had within them the seeds of further conflict! Truces were, as Grotius and Gentili wrote about them, a “rest from war”—a temporary break from fighting. And they didn't change the fundamental underlying reasons for war or ongoing war. They were merely a suspension of hostilities.

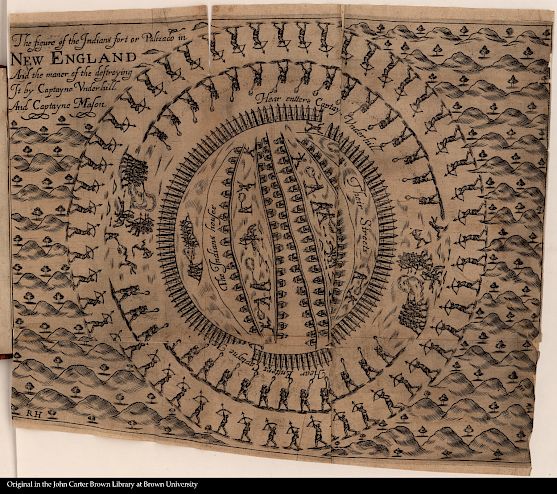

This insight helped me reexamine cases in which truces were less formalized, but the language about truces was still essential to the organization and justification for imperial violence. Truces were tragic in the sense that there was no alternative. In all these settings —and even today, as we might talk about later— people reach for truces in desperation to avoid ongoing fighting. But since they are merely a break from war, and there is no requirement to produce justifications for ending truces, they often set up the logic and the probability of more violence —and this is also tragic. But what is more, I found that violence recurs with extra force when truces broke down. So, there's another way that truces really mattered, and that is that they introduced a kind of current of electricity into imperial violence. Sides did not declare that they were ending truces, they just took up fighting again, now using the logic of punishing truce-breakers to justify extreme violence. The punishment of truce breakers was charged, in other words, with extra intensity. And with the notion that “all bets were off”: it was justified at that point to kill civilians, seize property, enslave opponents, without any sort of limit. In other words, truces were not only inadequate as peacemaking instruments, but they were actually capable of ratcheting up the intensity of violence. The massacre at Mystic, in 1637, is an example of unfettered violence considered justified because the victims were represented as truce breakers.

DRQV: This, sadly, resonates all too well with my own experience as a Colombian —where we have also had a recent inconclusive attempt at peacemaking. But I think that something particularly interesting about this dynamic is that it allowed actors, both European empires but also non-European players, to shift between the registers of violence against rebels vis-à-vis enemies (p. 165). This overlaps, in a way, with the division between “policing” and “military actions.” Indeed, a truce can be celebrated both with a “military enemy” and with a “rebellious subject” —and the ambiguities of such construction was widely exploited. What continuities can we see in the ways in which the porous frontier between these two violent worlds is crossed by imperial agents?

LB: A finding that I thought was particularly fascinating was this “toggling” back and forth between the labelling of opponents as enemies and rebels. Both enemies and rebels can be treated with extreme violence, of course. So, both of those labels were very useful to imperial powers. After all, they could treat rebels very harshly —punishing them as traitors. And at the same time, enemies in the early modern world could be treated without mercy. On one level, it seems as if there isn’t much distinction between these categories, but they do indicate a different sort of imagination of the imperial polity—and of the relationship of the peoples who were being incorporated (or not) within empires. It was this toggling back and forth that I found to be itself a core modality of imperial violence.

Late in the book that I point how this strategy was being used, in particular, in settler colonies. And it is character of imperial violence that continues up to the present. The contemporary example that really resonates here is Ukraine. At the point of the invasion, Putin described the conflict not as a “war” but as a “special military operation”—basically an exercise in imperial policing. A year later he reverted to the language of “war”. This toggling between treating people as rebels and enemies was part of the imperial repertoire. There has been a lot of very good writing of late, in particular Natasha Wheatley’s recent book, about temporality in international law, and I think the rapid alternation of registers is another element of temporality, one that’s quite interesting. It constituted a structural element of these conflicts.

DRQV: I do have a lot of questions about contemporary empires and about the relationship between past, present, and perhaps future. But before to turn to that, I also wanted to highlight that something you do note in the book is that non-European polities and peoples also creatively engaged with these legal categories. So, it is not that they were passive, powerless recipients of imperial violence (although, of course, they are the losers of this story in terms of land or power). But you also show how, in different places, local elites also used these legal categories in their advantage —sometimes claiming to be loyal subjects or proper external enemies, depending on what gave them more leeway in this context of fraught political violence.

LB: That's very well said. And that indeed, is a point that I emphasize because I think it is important to point out that Indigenous polities, or non-European polities, were participating in these ways of narrating war in legal terms from a very early point. There is a tendency in the history of international law to wait until we see Indigenous elites entering into discussions using international law language coined by Europeans to recognize their participation in international law. But ways of describing war and violence I trace in the book actually cut across chronology and regions. People produced intelligible legal claims because they wanted to use the law to their advantage! That is why you see polities producing, sometimes simultaneously, arguments about being loyal or potential subjects worthy of protection and being enemies with sovereign rights to make war, depending on what was more strategically effective in any given context or moment.

DRQV: Now I want to turn to the militarization of empire that we hinted at before. A central arc of structural transformations in your story is that of the militarization of empire in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This is something you have also studied, in a separate book with Lisa Ford, in relation to the British Empire (Rage for Order, 2018) and earlier in Law and Colonial Cultures. But it seems to me you are making a broader point in this book. Can you tell us more about the drivers of these transformations? How do notions of “protection” justify an increased militarization of inter- and intra-imperial relations?

LB: There are two key elements of this global transformation in the long nineteenth century, both treated at some length in the book. The first has to do with the switch in the mid-eighteenth century towards a language of European authority to make and regulate the laws of war. I locate the increasingly robust language about European authority in the context of these small wars in and on the edges of empires. It's very striking that this trend occurred in places where European empires still only had very incomplete control. They were claiming a more robust authority to regulate war than they had. And they began to articulate this claim before the publication of Vattel’s The Law of Nations, with its claims about states as the elemental units of the law of nations and the laws of war.

The second part of the argument has to do with what I call “protection emergencies.” As Europeans were militarizing across the globe, they gave standing authorization to captains and commanders to make their own decisions about the use of force—with some very general instructions about how they should do that. One of these key general instructions was that they should protect imperial subjects. A lot of the small acts of violence (and some of the small wars actually labelled as “wars”) began with these protection emergencies—either imagined or perceived threats to imperial subjects. Commanders stepped in and used force in whatever way they decided, on the spot, to be both justifiable and practical. So global militarization, even without war, expanded imperial power, through use of “small” violence across the long nineteenth century.

DRQV: I wanted to point to something that you talk about in the in the start of the book, and it's this idea of “limited” war, or “contained war.” Because what you show in a chapter that an outcome of this militarization is that captains (or any kind of military leaders on the frontiers) were suddenly expected to make legal judgments on the protection of European interests and subjects. At the same time, they only had authorization to embark on “limited violence” —nobody in the metropole wanted than an intervention in a local emergency threatened the risk of a global war. Can you tell us more about how these captains became “judges” of the peace or the law?

LB: That's precisely right. Commanders were charged both with protecting subjects and with not starting major wars. And they were supposed to calibrate the use of violence so that it didn't get out of hand, but there were very few controls on what they did. What happened was an ex-post-facto rationalization process. In case after case, we find them writing to superiors with justifications in the wake of violence, not before it happened—not asking permission to intervene by force but looking for exculpation later. In parallel to what I was saying before about the way that the calibration of small violence opened the door to extreme violence, atrocities also occurred following protection emergencies. One way in the sequence happened was through the movement from the protection of subjects to the protection of imperial interests. For instance, in settler colonial contexts, serial small violence ratcheted up anxieties about a systemic threat to imperial subjects and interests, and could trigger very extreme violence. There was a very, very vague idea of “imperial interests” that included, in some cases, simply “public order”. Imperial agents and officials claimed that they were keeping the peace, even when they engaged in extreme forms of violence. Lisa Ford’s recent book on “the king’s peace” in the British Empire looks at dynamic, from a different angle.

DRQV: And that brings us to the last question I wanted to ask you. How do we think about your book in relation to our contemporary challenges (which sound painfully familiar to the patterns of violence that you trace in your book)? Today increasingly militarized empires continue to exploit the ambiguities of truces; oscillate between police and warlike operations; and transform precarious outposts into permanent settlements. As you note in the prologue, the book has helped you “to think critically about war in [your] own time” —drawing from early concerns related to “limited war” in Vietnam all the way to the twenty-first century (xiv-xv). How does your work help us understand, and critique, these contemporary practices? And if you have the appetite for it, I would be very curious to see if you would connect this to the broader debate that we have been having about anachronism in global legal politics and the challenges of intervening in the present as historians of international law.

LB: So, one of the things that I found most striking—but also disturbing—about this project was precisely what you just alluded to. Many of these ways of organizing and describing and justifying violence continue into the present. And the conclusion of the book is partly about these continuities. As it turns out, they seem even more relevant than they did when I was writing the book. I had before me, as I was working on it, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and some of the ways (as I described earlier) in which imperial language was used to justify the invasion on the part of Russia. I also was thinking about the “war on terror” and its very broad authorization for violence—which has some echoes from what I just described of open-ended violence in globally militarized empires of the nineteenth century. Then as now, one of the key issues is about where to fix the responsibility for the decision to use lethal force.

I did not have sharply in my mind as I was writing the ongoing war in Israel/Palestine. But, of course, just as the book was in press, this latest round of atrocities began in the Middle East. And they have been very much on my mind in relation to some of the ways of organizing and justifying violence that I found in empires.

A central theme of the book is the perpetual preoccupation with how to limit violence. I think it is important to consider that even imperial aggressors at times worked to limit violence—to calibrate it and prevent it from getting out of hand. A lot of the truce making that I described earlier represented genuine attempts to limit violence and its effects—and to pause fighting in ways that would, in fact, save lives. But the tragic dimensions of these practices of limiting violence are also apparent. They could open the door to atrocity.

I have been thinking a lot about truces and truce making in connection with the current war in Gaza. Many of us have been advocating a ceasefire, and there's a lot of political energy behind that call. I agree with that position myself and support it. And yet, I've been sitting with this realization about the tragic qualities of ceasefires and truces and their capacity to structure more war —and potentially stage dramatic escalations of violence in their aftermath. Unfortunately, that doesn't leave me with a lot to say about how to avoid or stop atrocities. In a sense, I sit with the tragedy that my historical actors also experienced: it is morally important to try to limit war. And yet, these limitations of war have their own ways of structuring further violence.

The main conclusion that I come to in the book is that we should recognize these dynamics, and keep them in mind. They lead one to be highly skeptical of anyone who is claiming the capacity to keep “small” wars small.

DRQV: I think that's a wonderful point to take home—especially if home is, as it was for me, a place like Geneva, Switzerland. There, a lot of the conversations about the laws of war or international humanitarian law were perhaps too confident about the lofty dream that law can tame violence. I think it's good that you remind us of that violence and law, alas, are not necessarily opposites—and that tragedy is not something we can entirely do without. Thank you very much! Would you like to add anything else?

LB: Thank you, Daniel, for the great conversation! I really appreciate the opportunity to bring together global historians and historians of international law in a discussion about violence and war.