Historicizing a planetary future: A discussion with Emma Rothschild on the convergence of climate science and historical thinking in the “1800 Histories” project.

TPF Executive board members Glenda Sluga and Heidi J.S. Tworek interviewed Emma Rothschild on her latest project “1800 Histories”; a collaborative effort to bring together climate science methodologies and various micro-histories of methane production, and to push historical scholarship towards a global history of climate change.

GS: Throughout your career you have tried to find ways of engaging environmental questions in your historical and public writing in innovative ways. We have seen your latest exciting project "1800 Histories", which is described on its home website as ‘an effort to understand the local circumstances of more than a thousand sites -- the ultra-emitters of methane gas -- that are of outsized importance in the causes of climate change.’ How did you come to conceive of this project?

ER: It's very nice to be talking. I had no idea, when the 1800 Histories project started, of how capacious it would become. But I do have a specific answer about how it began. In early February 2022, I had been reading a brilliant realist novel from 1948 -- Fire, by George R. Stewart -- and thinking about the global, abstract quality of contemporary conversations about climate change. There was an article in Science about methane, the greenhouse gas, reported on in the New York Times on 5 February 2022, that used data from a spectrometer on the Copernicus 5 satellite to identify the locations of around 1800 sites of very large methane emissions worldwide. I read the Science article and was captivated by the possibility of using the satellite data to think about a macro, global problem -- climate change -- through the micro-histories of specific, local sites. Our centre, the Joint Center for History and Economics, has a website, Visualizing Climate and Loss, where historians and others write short essays about subjects of contemporary interest. (It was launched in January 2020, a couple of months before the COVID lockdown, so there has been a lot to say.) I read the longer version of the Science article on ArXiv.org, and wrote about it on the Visualizing site on 22 February 2022. The essay began "Spectrometers do not see history," and went on to speculate that the methane data could "be the starting point for an historical inquiry: or for 1,800 inquiries into the history of climate change."

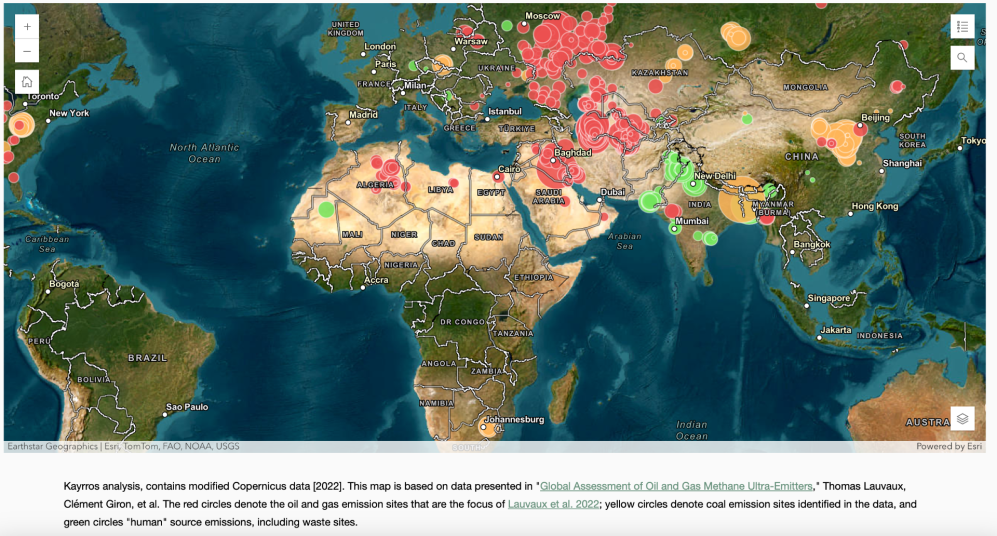

This wasn't really something that I thought I would be involved in myself. But I did write an enthusiastic letter to the lead author of the Science article, the French climate scientist Thomas Lauvaux, and asked him if he could send me the "plumes dataset" mentioned in the ArXiv.org version of the paper. He sent me the link the same day, and I started playing around with the data. The Science paper was about emissions from oil and gas, and the complete dataset included emissions from coal mines and from "human" sources such as landfills. There were the dates of the observations, the quantities of methane observed, and the longitude/latitude coordinates for the events. So, it was possible to find the (approximate) location of the emissions on a world map.

It was exciting, and everything happened surprisingly fast. Thomas Lauvaux sent me the link to the data; my colleague Ian Kumekawa uploaded it into a Google map later the same day, 10 February 2022. We had a first draft of the 1800 Histories website online on 14 March 2022, with a single "micro-history," about Allegheny, Pennsylvania.

The website project, after this enthusiastic beginning, turned out to be a much more deliberate process. It was only launched publicly more than a year later, after a great deal of discussion about how to solicit contributions, micro-histories, some and not all of them to be written by historians, and how to review them. In a way it was like an experiment in editing an online global journal. It was exhilarating because so many people saw the point of the project and its potential. I went for a long walk along the Charles River with my friend and colleague Abhijit Banerjee, and he suggested an eventual crowd-sourced project of micro-histories. He also encouraged us to identify writers who are themselves or have been based in the sites observed, from Dhaka to eastern Ukraine. This has been one of the most exciting parts of the project.

The project has led to new kinds of collaborations, particularly with climate scientists. Thomas Lauvaux is now an associate of the Center for History and Economics, and I've visited him at the University of Reims. At Harvard I'm involved in a cooperative project with Steven Wofsy in Earth and Planetary Sciences. These are all conversations that started out of shared interests, rather than because of any sort of institutional exhortation to interdisciplinarity.

There some rather deep questions raised by the 1800 Histories project -- even questions about different ways of seeing the world -- that I'd be really happy to talk about further with the two of you. The project was connected, for me, to a longstanding interest in approaches to global history. It was a way of linking the micro to the macro, and the local to the global (as I tried to do in The Inner Life of Empires and An Infinite History.) It was also, in a very literal sense, a connection between the view from below, or history from below, and the view from above.

But the continuing conversations with climate scientists have called into question some of these conceptions. What does it mean, for example, to see something from below? Is it to see events at the level, or from the perspective, of individuals who saw the events, or remembered then? Or at ground level? Or deep underground, as in the records of a legal case I've been reading recently, about an accident in an underground trona mine, below one of the methane emission sites in Wyoming observed in the satellite data?

The project started, as I mentioned, with the observation that spectrometers do not see history. But what is it like to see events with instruments (spectrometers and the anemometers that measure wind directions)? Or with the digitized (quantitative and qualitative) data that are historians' sources? Climate scientists work in collaborative groups, and historians have the illusion of working alone. But who are our visible and invisible collaborators, and how does our critique of (digital) sources resemble the climate scientists' critiques of their own sources? Spectrometers do suggest (important) questions for historians; that has at least been the premise of the project.

Can history suggest important questions for climate science?

One last point. The 1800 Histories project has been shaped from the outset -- starting with its origins in our COVID-lockdown era website -- by the participants' concerns with the climate change of our times. It has also been shaped in profound ways by our students' questions about climate. Energy history was for me a return, of sorts, to much earlier interests. (My first book, published in 1973, was called Paradise Lost: The Decline of the Auto-Industrial Age, and I wrote 10 or 12 articles in the New York Review of Books about energy and the environment over the course of the 1970s.) The Joint Centre for History and Economics, thanks to Paul Warde, Meena Singh, and Sunil Amrith, has had a longstanding programme in energy and environmental history, starting in the early 1990s. But in relation to the new website, the most important influence, for me, has been teaching an undergraduate course at Harvard called Writing Histories of Climate Change.

There is a convergence, here, between the concerns of climate scientists and historians that may even help to explain why the collaboration has seemed so promising, at least for me, over this initial period. My colleagues in climate science have the sense, from time to time, that they produce amazing data, and have no idea who will use it. Historians have the sense that we write things and have no idea who will read them. The website has been a way of thinking about the uses of research, and it has even inspired new questions about what sort of research to do.

HJST: Thank you for that rich first answer that raises so many fascinating further points for discussion. Let’s take you up on the suggestion to talk about how the 1800 Histories project raises questions about different ways of seeing the world. How do you think that this project speaks to new methods of writing, mapping, or thinking about global history?

ER: To see the earth from above -- the satellite's eye view -- has been one of the enduring similes of long-distance or global history. In 1982, Bernard Bailyn wrote of the "challenge of modern historiography" that "to see the whole of the entire set of interrelated systems that impinged on preindustrial America one would have to circle the globe like a satellite;" history was itself a "transnational" enterprise, in which the (extended) Atlantic world was part of a "global system." To look down from a great height was to be able to see patterns -- in the movements of people or commodities -- that were invisible if glimpsed only from the surface of the earth.

There is some of this perspective in the 1800 Histories project. One of the discoveries, when we first mapped the data, was the vast arc of methane emission sites across the territory of Russia, along the pipeline routes to the Black Sea from the Gulf of Ob on the Arctic Ocean. But I've also been very struck, particularly in the collaborative project with the Wofsy group, who launched their own satellite, MethaneSat, in 2024, with the extent to which the climate scientists are themselves interested in seeing the sorts of things that historians see, landfill sites or coal mines or refineries. There is the amazing technical achievement of being able to see so much at such high resolution, and there is also the question of what it is that the satellite or the spectrometer sees. The data provide a view of where climate change is happening. Or rather, of where the causes of climate change -- in this case, methane emissions -- are happening. But why are the emissions happening in these particular places? And why does it matter to know where they are?

History happens in space as well as time, as environmental historians have shown for so long. I've always been interested in the connection between places (the old streets of the small French town of Angoulême, for example) and far-off events. But the importance of place has been compelling in the work I've done myself for the 1800 Histories project. There are longitude/latitude coordinates of an event (a plume of methane) in the recent past, and the historical question is about what was really happening in the place that the coordinates describe; what it looked like, who was there, was there a pipeline, or an underground coal mine, or an industrial site? If there was a plant or a landfill, how long had it been there? Who lived in the vicinity? What was it like to live there or work there? Is the place surrounded, like a methane emission site in southwest Wyoming that I've been working on recently, by the grey-green landscape of the sagebrush steppe? Or is it the site of multiple sorts of pollution, as in an old-established coal-mining region of eastern Serbia, developed in the 1880s near the Roman city of Viminacium, and the resting place, now, of a Middle Pleistocene "steppe" mammoth?

The climate scientists with whom we've been working see things with different technologies, in the sense that they see with new instruments, in collaborative teams, and through very large projects (as in the live feed of the launch of MethaneSAT.) Thomas Lauvaux described some of the limits of detection in a fascinating conversation with Joule Voelz of the 1800 Histories project. But historians too see things with images and details and (historical) statistics.

Bailyn used a different, more startling simile of seeing from space that is particularly evocative in relation to the methane project. It was about the preciseness and profusion of information in respect of the history of slavery, in which, Bailyn wrote in 2002, "we are all in some degree morally involved," as historians and others are, now, in climate change. The simile was of looking upwards at the cosmos from an orbiting satellite, and not down towards the earth. The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, with its statistics about the slave trade, "skeptical, empirical [and] source-bound," in Bailyn's description, was like a vista of space; "astronomers knew of the vast range of cosmic phenomena before the Hubble Space Telescope existed, but that extraordinarily perceptive eye, coursing freely above the earth's atmosphere, has led to a degree of precision and a breadth of vision never dreamed of before and has revealed, and continues to reveal, not only new information but also new questions never broached before."

The 1800 Histories project has been intensely collaborative from the outset, and this may be related to new methods of writing global history. I've certainly been writing much shorter pieces (although one of the conditions of writing history, now, is to be distracted all the time) and thinking much more about visual evidence. Essentially everything on the site has been edited collaboratively with my colleague Diana Kim, and with Connor Chung and Oliver Riskin-Kutz, who joined the project as undergraduates. The site has also been shaped from the outset by conversations with Franziska Exeler, about photography and invisible histories. These are scholars with very different interests in time and space, who have been thinking about collaborative writing.

As to mapping global history, the methane project has been a return, in a sense, to one of the great themes of early modern history over the past several decades, the critique of cartographical sources. Maps have become a part of daily life, now, in a way that was inconceivable to all but the most intrepid and subsidised explorers (or soldiers) in the early modern world. The first step, faced with the longitude and latitude coordinates of a methane emission site, is to look for it on "the map," or on any map. But the maps are vertiginously complicated. Literally so, as one zooms down, or "in," to a place that is recognisable as somewhere with living things, flora and fauna and an historical past. It is always daytime, on the maps, and the sun is always shining. Even the latitudes for which there are no data about methane emissions -- the cloudy north and the tropics -- are there, bathed in light. It is early morning, in Google Street View, and the streets are almost deserted. The maps are composites, in arcane ways. The view of the area that is at the centre of the Spring, TX micro-history has a chyron-like legend, in the 1800 Histories map, that acknowledges "Earthstar Geographics | CONANP, Esri, HERE, Garmin, FAO, NOAA, USGS, EPA." This is a satellite view, or "layer." But the default views, the maps of "terrain" or "traffic," are also composites. The commercial landmarks change all the time or are there in some maps and not in others; the Bitcoin ATMs in the streets around the Exxon Mobil headquarters in Spring, TX, or the Chick-fil-A and the dental clinic in the middle of the campus. It is only the infrastructure of road transport -- Interstate Highway 45 (I-45), in the micro-history of Spring -- that is constant.

There are the maps, in turn, of the landscape below the surface, as in the maps of buried oil and gas wells in the Texas Railroad Commission's Public Viewer, or the pipelines in the National Pipelines Mapping System of the US Department of Transportation, which are "only visible at zoom level 14 or lower." The 1800 methane sites were themselves identified on the basis of the topography of the locations, and also of an understanding of what was happening immediately above the surface; maps of wind speed and direction.

So, maps have been at the centre of the methane micro-histories, as of so much of global history. But the project also provides a sense of the extraordinary possibilities of an eventual critical history -- a cartographical history -- of the multiple, opaque, constrained, and multi-billion-dollar mapping industry, or public-private partnership, of the 21st century.

In relation to new methods of thinking about global history, I do think that the methane histories project has been helpful in making connections between local and global histories, or between micro- and macro- histories (which are not the same thing.) The question of space, or place, is again of central importance. Methane emissions are a form of pollution, and all pollution is local, in the sense that pollutants, even if their consequences are global, emanate from a particular place, and pass through local environments, even as they drift over very long (vertical and horizontal) distances. So, there is a vector of material contiguity connecting local and global pollution. Methane is widely described as an ethereal sort of greenhouse gas, vast, invisibleand odourless. But methane leaks have had terrible consequences for coal miners and other mine workers over more than two centuries, and the history of the global environment has been oddly distinct from labour history, or the history of occupational health and safety. Methane emissions are also co-located with emissions of other pollutants, with much more immediate consequences for local communities and for human health.

Then there is another vector of contiguity over space that is central to the micro-histories of industrial sites. These are the vectors of what economists call "intermediate inputs," or flows of commodities that go from one enterprise to another, rather than entering into the final demand of consumers or governments. They are "used up," in principle, in the process of production. The methane emission sites in southwest Wyoming are an interesting example. The plumes are likely to have emanated from the mines and associated processing facilities that produce the obscure mineral trona. But trona is not something that consumers buy. It is used in the production of an almost equally obscure commodity, soda ash, that is transported, in turn, to industrial enterprises, in Brazil, Indonesia and elsewhere, and used in the production of glass, soap, paper and, in prospect, of the batteries that are so essential to the new "green economy." The process uses energy, and produces pollution, along a supply chain that is itself a connection between local and global histories.

Are these promising ways of thinking about global history? I am excited, as a historian of economic life, by the possibilities of looking at the causes of climate change in the local histories of places that are connected, over very long distances, by economic exchanges. It would be interesting, too, to look at the business history of the companies that operate the sites -- the trona industry of Wyoming is owned, in large part, by long-established Turkish, Indian, and Belgian enterprises -- and at the history of the changing technologies involved, since the early modern period, in the case of soda ash.

There is even the prospect of new ways of thinking about climate change. Public discussion of climate change has been much more about consumption than about production. Miles driven in passenger cars are the "currency," more or less, of calculations about GHGs. Even methane, which is the most intermediate of the GHGs, in the sense that it is emitted almost entirely in the course of production, is made intelligible by being compared to consumption (as in the US Environmental Protection Agency's Coal Mine Methane Units Converter; "equivalent to GHG emissions from either one of the following: Gasoline-powered cars driven for 1 year [or] Miles driven by an average gasoline-powered passenger vehicle.")

The 1800 Histories project has been concerned, by contrast, with the consequences of production, in different places and at different times. This is itself a way of thinking about climate change.

Director, Joint Center for History and Economics

HJST: A further question is about the specific role for historians. An article in The Conversation in June 2024 argued for the importance of climate social scientists, noting that media coverage really only focuses on climate natural scientists. How do you see the role of history in this broader conversation, whether as a social science or as a means of dialogue with climate scientists?

ER: Historians are essential to an understanding of climate change that is concerned with a causal understanding of emissions of GHGs, in space and time. If the causes of climate change are to be found in large, abstract, diachronic conditions -- modernity or consumption or western civilization or capitalism or growth -- then I don't think there is very much that historians can add to the inquiry. But if the inquiry into causes is more specific, historians become of central importance. Why were there depletion allowances for oil and shale in the United States, and what was the "political economy" of the regulations that favoured the automobile industry over the course of the 20th century? Why was the miners' strike of 1989 in the Donbas region of Ukraine, immediately before the fall of the Soviet Union, about safety and pollution, as well as about political reform? What is the municipal politics of landfill sites in Delhi? Historians can tell stories and explain what really happened. To understand why something really happened is in turn to have at least the possibility of changing it.

The project has certainly made me much more optimistic about collaboration, as well as dialogue, between climate scientists, historians, other social scientists, and other scholars in the humanities. I think this is already happening, particularly among younger scholars, without anyone thinking about it as an objective of educational or research policy. Economists have been at the centre of discussions of the "global" costs of climate change, including mitigation and adaptation. But they have also been thinking about adaptation in particular places and times. The economist Ed Glaeser, who is now working on climate adaptation in very large metropolitan areas, lists five books that have influenced his work on the urban economy, Jane Jacobs’ The Death and Life of Great American Cities and The Economy of Cities, Robert Caro’s Power Broker, William Cronon’s Nature’s Metropolis [and] Charles Rosenberg’s The Cholera Years.

One of the people who has been involved with the 1800 Histories project from the outset, starting as a PhD student in economics, Dev Patel, has a project on using satellite data about flooding in Bangladesh, jointly with a colleague in the Wofsy group. Two other PhD students from the Wofsy group, Ju Chulakadabba and Ethan Manninen, have written micro-histories of places they have seen in their data. Then there at least a hundred undergraduates who have so far written micro-histories of the sites in the 1800 Histories map, as course assignments in history and politics courses; some of them will surely become historians.

GS: This is making me think harder about whether ‘planetary histories’ is a fruitful provocation, or whether we are better being guided by the specific project of writing histories of climate change. Do you find any use in the provocation of the ‘planetary’ and the kinds of debates it has led to so far?

ER: Dipesh Chakrabarty has said of the planetary and the global that the "two perspectives should be integrated in historical studies," and that humanist historians should be "sensitive to the large- and the small-scale -- and thus to the human and nonhuman (both living and non-living) -- in whatever histories they are writing." This could be the maxim of the 1800 Histories project.

To think about climate change is to have an imposing sense of the infinite. It is also to try to think about something, or anything, that can be done to make the consequences of climate change less awful. This is almost always to think on a smaller scale. I was struck by how many of the undergraduates who wrote methane micro-histories as class assignments chose places close to where they or their families had once lived. This turned out to be a way of thinking about other (co-located) forms of pollution, and also about what individuals and associations were doing, in those particular places, to reduce the emissions that are the causes of climate change.

To follow the worldwide vectors of intermediate inputs, as I have been trying to do, is to think about the supply chains of the incipient, global "green economy." This is a way of connecting the small-scale and the large-scale, and it is also to imagine what it would be like to have a serious, historical inquiry into the entire requirements of, for example, the electric vehicle industry: from the trona mines of Wyoming to the cobalt mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo to the glass factories and the tires and the energy required for the AI used in the maps, and from the charging stations and the asphalt used in road production to the afterlives of the vehicles and their batteries over at least a generation.

Everyone in the world should have access to electricity. Everyone in the world should have access to soap and glass and paper, and thereby to the processes of production into which soda ash has been an intermediate input. So, to think about the sites of methane emissions is to think about the possibility of loss. The history of soda ash production is not an entirely dismal narrative. There are new, less polluting technologies, there have been major improvements in mine safety, there are regulations that reduce methane emissions. But Lake Gosiute, the vast Eocene Lake, once filled with crocodiles, lies below the trona deposits of southwest Wyoming, just as the woolly mammoths of the Pleistocene, like the ruins of the ancient colony of Viminacium, lie below the open-pit coal mines of Kostolac in Serbia.

To think about the localities in which climate change is happening -- its consequences and its causes -- is to have a sense of melancholy and hope. One of the obligations, in the new trona projects now under discussion in Wyoming, is to try to protect the habitat of the sage-grouse, which is an endangered and charismatic avian. The grey-green expanse of the sagebrush steppe, which is heartbreakingly beautiful, and which has its own long history, is itself at risk. This, too, is a story of planetary and global history.

Emma Rothschild is the Jeremy and Jane Knowles Professor of History at Harvard University and the Director of the Center for History and Economics. Learn more about the "1800 Histories" Project here.

Glenda Sluga is the joint chair of the Department of History and the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at the European Union Institute in Florence, Italy, as well as a Professor of International History and Capitalism. Prof. Sluga currently serves as the President of the Toynbee Prize Foundation's Executive Board.

Heidi Tworek is the Canada Research Chair and Professor of International History and Public Policy at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. Prof. Tworek currently serves as the Vice President of the Toynbee Prize Foundation's Executive Board.