How China’s Environments Changed its Modern History: An interview with Micah Muscolino

It is hard to imagine the environmental calamities of our age without invoking China today. The “world’s factory” – as it is colloquially and sometimes derogatively called – has come to forefront of many discussions about the need to avert the dangers of planetary degradation. Images such as the thick carpets of smog covering Beijing or gripping documentaries, such as Death by Design (AMBRICA, 2016) and Plastic China (Jiu-Liang Wang, 2016), have revealed how China’s social and natural landscapes have experienced the ‘Anthropocene’s’ coming of age. In such narratives, the environment in China is usually seen as the victim of unfettered industrial production and global consumption starting with the country’s ‘reform and opening up’ period in the late 1970s. But to what extent does this periodization and the logics of the Anthropocene that rest upon it make sense against the longer historical record?

A wave of scholarship has scrutinized the abstract idea of the environment in China’s restless history over the past two centuries. Bracketing the origins of the today’s environmental crises exclusively within the globalization debate is to miss something important. Namely, ecological thinking featured prominently in the country’s experiences with modernization, colonialism, and nation-building starting in the long 19th century. Micah Muscolino’s work is a great example that rethinks the conventional framework of modern Chinese history. Muscolino shows how the making of Qing, National, and PRC rule were often built on its relationships to natural resources. He has also come to see many similarities between today’s environmentalist transformations and China’s past. China stands, as he asserts, at the heart of the world’s present-day predicaments.

The Toynbee Prize Foundation had the pleasure of interviewing Professor Micah Muscolino. He is the author of two acclaimed monographs, Fishing Wars and Environmental Change in Late Imperial and Modern China (2009) and The Ecology of War in China: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938-1950 (2015). With his Ph.D. in Chinese history from Harvard in hand, Muscolino taught at St. Mary’s College of California, Georgetown University, and the University of Oxford, before taking up the Pickowicz Endowed Chair in Modern Chinese History at UC San Diego in 2018. He took the time to tell us more about the China’s past and present entanglements with the environment.

—Rustam Khan

RUSTAM KHAN: What began your interest in the environmental histories of China?

MICAH MUSCOLINO: I got into the environmental history of China in a rather serendipitous way. As an undergraduate at UC Berkeley and later in my first couple of years as a graduate student at Harvard, I was dead-set on studying Chinese social history, which still fascinates me and influences my work in many ways. In the summer after my second year of grad school, I visited archives in Taiwan to look for sources on the working population in China’s coal industry during the Republican era (1912-1949) as a potential dissertation topic. I ended up with an entirely different topic.

During the first of many trips to the archives of the Institute of Modern History at Academica Sinica, I stumbled upon a folder of documents labeled “cuttlefish dispute.” This instantly intrigued me simply because I wanted to know what was going on and why people were fight over cuttlefish. I soon abandoned my plan to research coalminers and shifted my focus instead to China’s fishing population.

When I returned to Harvard that fall and started getting familiar with scholarship on fishing societies and fisheries economics, I quickly realized that the environment and resource management were really at the heart of everything I was reading about. As my research moved forward, it dawned on me that I couldn’t do justice to the topic I had chosen without taking the environment seriously. Interactions between the environment and society became central to what I was doing, which opened my eyes to whole new dimensions of Chinese history.

RK: How do you see the attention on China’s ecological path today shaping your work, or vice versa?

MM: China is facing tremendous environmental challenges today, as we all know, which I suppose gives my work greater relevance. Because China’s environmental challenges are also global challenges, studying Chinese environmental history allows for a deeper understanding of the ecological dilemmas facing the contemporary world and a better appreciation of the range of options available to address them. Examining China’s place in global environmental history has also pushed me to think and write in ways that are not confined by the territorial boundaries of the nation-state. In a way, environmental history requires that you to look at everything – even local history – in global terms. At the same time, local histories can call attention to the complexity and specific iterations of global processes. That’s the beauty of environmental history. It enables you to oscillate back and forth between different scales of analysis, employing macro- and the micro- perspectives.

In a way, environmental history requires that you to look at everything – even local history – in global terms. At the same time, local histories can call attention to the complexity and specific iterations of global processes. That’s the beauty of environmental history.

RK: In your first book, you write how coastal communities evolved from subsistence economies to territorial zones managed by modernizing empires and states. Is there something peculiar about China’s case?

MM: One thing that might be peculiar to China is that its coastal communities, at least in the period and places that I studied, were by no means subsistence oriented. Fishing had been enmeshed in a highly marketized economy since late imperial times. The commercial networks that turned fish into commodities depended on systems of informal regulation maintained by fishers from different native-place groups to function. One of the things that my book tried to illustrate was how conflicts surrounding fisheries grew out of tensions among: the social institutions that Chinese fishing communities devised to regulate access to resources and markets; the Chinese nation-state’s claims to fishing grounds in what it tried to define as its territorial waters; and the transnational exploitation of marine fisheries by what Bill Tsutsui has called Japan’s “pelagic empire.” These multiple forms of territoriality had tremendous implications for resource control and exploitation. Local arrangements were not capable of coping with larger-scale ecological pressures from Japan’s mechanized fishing fleet, while alliances between competing regionally-based fishing groups and overlapping Chinese state agencies, which claimed the power to administer and tax the fishing industry, intensified contests of control over scarce resources. I’d say the process was a bit more complicated than an evolution from subsistence-based coastal communities to the territorial zones of modernizing states and empires.

RK: Contestation over maritime waters is obviously omnipresent in the South China Sea issues today, but it is almost exclusively understood in geopolitical and military terms. Are we missing something here?

MM: The obvious thing that’s missing is the environmental dimension. Expanding some of the arguments made in my first book, I’ve written a short article about how overfishing in China’s coastal waters has fueled maritime disputes by causing the Chinese fishing fleet to venture into more distant waters in search of productive fishing grounds. I’ve also written about jurisdictional claims to hydrocarbon reserves put forth by China and the Philippines during the oil crisis of the 1970s that turned islets in the South China Sea into hotly contested areas. In addition to the geopolitical and military factors, contestation over resources and how that has developed historically also need to be considered when trying to understand recent maritime tensions.

RK: Your most recent book The Ecology of War in China tells a story of warfare that doesn’t focus on the battlefield. Instead, your main subject are the ecological flows that structure human violence. How did you come to write this book?

MM: In part, it was writing about the “fishing wars” between China and Japan during the 1920s and 1930s that drew my attention to the ecological impact of the full-scale war that raged between China and Japan from 1937-1945. The specific idea came to me when I was listening to a lecture about recent histories of the Second World War in China. The speaker, Parks M. Coble (University of Nebraska – Lincoln), noted that two topics – wartime refugees and the war’s environmental impact – deserved greater attention. It occurred to me that it might be possible to address both topics by looking at how the war’s environmental consequences contributed to the displacement of an estimated 90 million people that occurred during China’s conflict with Japan, along with the environmental consequences of that mass migration. From the beginning, the focus of the project was on war’s effects on society and the environment.

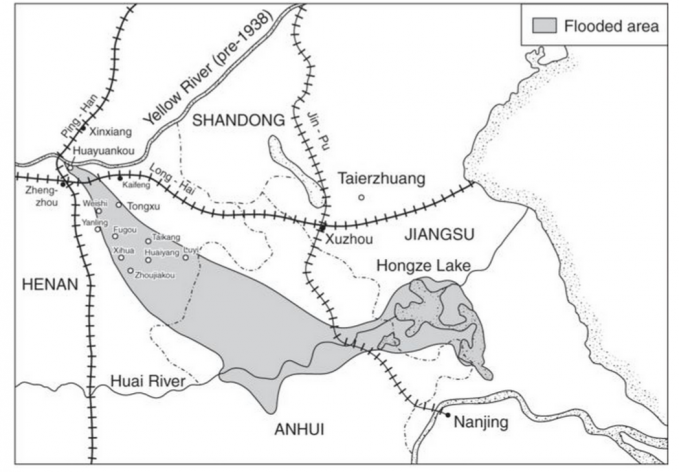

As I looked around for sources on refugees and the environment, a place called Huanglongshan (黃龍山) in northwest China’s Shaanxi province, came onto my radar. During the war, the Nationalist government resettled thousands of displaced people to Huanglongshan to reclaim uncultivated land for farming. Many of these displaced people came from disaster-stricken parts of Henan, on the North China Plain, which had a larger refugee population than any other province in China during the war. In addition to the Japanese invasion itself, as I came to find out, a sizeable percentage of Henan’s refugee population was displaced by two war-induced ecological catastrophes. One was the intentional diversion of the Yellow River in June 1938 by Chinese Nationalist armies under Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kai-shek) to slow the Japanese military advance. The other was the Henan famine of 1942-43, which was caused by several factors: war-induced flooding; an El Niño event; and the food demands of Chinese and Japanese armies stationed in Henan.

When I started writing the book, I was puzzled as to how to tie together all of the horrific environmental destruction and human dislocation caused by military conflict, flooding, famine, and refugee flight into a coherent analysis that had something meaningful to say about the relationship between war and the environment more generally. As I read through the documents that I had collected at archives in Henan and Shaanxi, I kept coming across the word li (力), which one can translate as “capacity” or “power” in English. Gradually, I started to envision energy as a thread that connected war, ecological disasters, refugee flight, and their second-order environmental repercussions.

As I read through the documents that I had collected at archives in Henan and Shaanxi, I kept coming across the word li (力), which one can translate as “capacity” or “power” in English. Gradually, I started to envision energy as a thread that connected war, ecological disasters, refugee flight, and their second-order environmental repercussions.

RK: What’s the big take-away of the book? Do you also find the connection between the refugee and environmental change in other historical contexts and the present relevant?

MM: The big take-away is that nature and its energy make war possible. When energy is used to wage war, it denies the use of that energy for other purposes. This distorts flows of energy between environment and society, which results in environmental destruction and human suffering of all kinds. I drew a lot of inspiration from works on refugees and the environment from the fields of geography and political ecology, but the environmental history of refugee migration has not attracted much attention. I wanted my research to help fill that gap. Another thing I tried to do in the book was to show how the displaced people who returned to their homes in Henan after the war’s end tried to restore some degree of normalcy by redirecting energy towards the rebuilding of agricultural ecosystems made up of farms and villages. Taking account of this postwar reconstruction was a conscious effort to move beyond environmental histories that adhere to a declensionist narrative – a story of decline and loss. Although their subject matter varies enormously, environmental histories of China generally reproduce this metanarrative. I tried to step away from it by discussing post-conflict recovery, but I’m not sure if I was successful or not.

I drew a lot of inspiration from works on refugees and the environment from the fields of geography and political ecology, but the environmental history of refugee migration has not attracted much attention. I wanted my research to help fill that gap.

RK: Why have these episodes of famine in China, before the PRC era, been more or less forgotten in scholarship and by general audiences in comparison to, say, the Bengal Famine?

MM: I’d say that the Bengal famine is relatively well-known compared to the Henan famine of 1942-43. I can’t really speak to why that’s the case. But one of the reasons why the Henan famine has received so little attention was because it was subsumed into a narrative in modern Chinese history, predominant until the early 1990s, that focused on the rise of the Chinese Communist Party. If there was attention to the Henan famine, or the Yellow River flood, they were put forth as examples of the Nationalist government incompetence, corruption, and illegitimacy. Henan’s wartime disasters were yet another explanation for the Communist Party’s seizure of power. If the disasters are subsumed into such a narrative, then their environmental and social dimensions are obscured. My second book was an example of more recent historiography that attempts to reassess the significance of China’s war with Japan, as well an effort to examine the environmental dimensions of war and militarization in modern Chinese history.

RK: The key word “metabolism” occupies a central role in your work. Can you tell us why and how a focus on its ecological nature helps us to understand warfare and social change?

MM: The notion of metabolism refers to the flows of energy that enable socio-economic systems to function. The concept helps us understand war and social change by reminding us that warfare requires energy. Militaries need food, fuel, and other raw materials – all of which are derived from the environment. It breaks down the division between nature and culture. I tried to show how the military metabolism shapes strategy, the fates of communities, and the course of environmental change. Since all military conflicts depend on nature’s energy, I hoped that applying the concept to World War II in China would open up avenues for comparative histories of war and the environment. In the case of my second book, it also made it possible to think about the Yellow River as an actor into the history of World War II, because the same energy that propels the river fuels warfare and people expended huge amounts of energy trying to control it.

In World War II, energy-intensive, fossil-fueled machinery transformed the metabolism of military conflict. But what is often overlooked is that exploiting fossil fuels on a large scale did not make other forms of energy less important. We tend to think of the Japanese military as a largely mechanized force that harnessed fossil fuels to inflict mass destruction upon its adversaries. But the war effort still made use of organic sources of energy on an extremely large scale. Both the Chinese and Japanese militaries still had to gather large numbers of troops and conscript laborers to move materials and supplies. Grain was needed to feed these people and draft animals were also brought into service for the war effort. During World War II in China, you had the harnessing of fossil fuels to power military conflict on a large scale, but also a simultaneous increase in the demand for biomass energy. That is one of the reasons why the war took such a heavy toll on the North China Plain. Because the environment was already highly degraded, and resources were in extremely short supply, the effects of armies trying to extract energy proved to be catastrophic.

RK: What historical issues do you plan to address in the coming years?

MM: Previously I’ve mainly researched the first half of the twentieth century, between the final decade of the Qing dynasty and the beginning of the PRC era. I’ve now fully moved into the post-1949 period, though I maintain some links to the Republican period.

I am currently writing a history of soil and water conservation in northwest China’s Gansu province from the 1940s until the early 1990s. My interest is in how conservation programs transformed the biophysical environment and altered the lives of people who depended on water and soil for their survival. My spatial focus is what is now Tianshui municipality in the eastern part of Gansu province, where the first soil and water conservation experiment station was set up in the 1940s by the Chinese Nationalist regime. After 1949 the area gained even greater prominence in the nationwide battle against erosion launched under the PRC. Based on extensive research in local archives and oral histories that I have conducted in rural villages, I’m examining the relationship between conservation that played out in the context in communist state-building and revolutionary mobilization, and agrarian societies at the local level. I’ve recently published an article on the gendered dimensions of conservation in Past & Present and I also maintain a research blog called China Water and Soil History Network.

Environmental histories of different parts of Africa and the American West have shown that local populations did not respond to the introduction and enforcement of state-initiated soil conservation policies. The local archives that I’ve consulted also contain records of tensions and conflicts related to conservation campaigns in rural Gansu, as well as how cadres and officials sought to address them. I’m trying to evaluate conservation and its consequences in the distinctive context of socialist China, showing how environmental management practices emerged from patterns of administrative intervention, popular resistance and accommodation, and state-society negotiation.

RK: Is there an active social justice component to your scholarship?

MM: Over the past couple of years, I’ve tried to engage more with questions of conservation, sustainability, and environmental justice. Environmental justice, as I understand it at least, means making sure that disadvantaged and marginalized groups do not (as often happens) disproportionately suffer from environmental hazards and that efforts to achieve sustainability do not aggravate social inequalities. Who shoulders the costs of sustainability? Who benefits from environmental management programs and who is disadvantaged? You can start to ask who the winners and losers are when it comes to conservation and what’s at stake if we don’t unpack the power relations under which decisions about environmental policy are made. In my own research, for instance, I’ve found that state-led conservation programs changed patterns of resource use in Gansu in ways that were often detrimental to the wellbeing of poor and marginalized rural communities. The question of environmental justice is something I didn’t address directly in my previous work, but it is something I think a lot about now.

RK: Do you have any advice for the younger generations interested in what you do?

MM: It might seem odd given that the pandemic has made doing fieldwork so difficult, but I’d advise them to go to the places that they’re researching. Get your boots dirty and walk around. Look at the landscape and talk to the people you meet. Even if you’re researching a period that’s relatively distant for the present, you’ll still reap substantial benefits. This really made an impression on me over the past few years. Before doing this research on soil and water conservation, I was mostly the kind of historian who goes to the archives, reads the documents, and perhaps looks at a few inscriptions and does a handful of interviews. But since I started working on the post-1949 period, at least before the pandemic started, I was able to do much more fieldwork. My ability to understand what was happening in Chinese local societies and the forces that drive environmental change have been tremendously enriched. When I still could, I read documents and went to the villages discussed in the sources. On a couple of occasions, I met and interviewed the people who were central figures in the documents that I was using. Asking people questions about the situations described in the documents enables a completely different kind of close reading and that’s been a breakthrough of sorts in the way that I do research. As soon as it’s possible again, I’d advise younger scholars to do fieldwork and walk around in the places they’re writing about.