Immigrants, Railroads, America, Germany: An Interview with Julío Robert Decker

People often ask scholars of history what, exactly, the discipline constitutes–what its unique methodologies are, what precisely its subject of study is, and what contemporary questions it offers to clarify. As our recent Global History Forum interviews have shown, one of the joys of the field is that it rejects the reassuring but often illusory national containers of traditional historiography, and that, precisely by doing so, it can help us, a twenty-first century readership, understand problems that exceed the boundaries of the nation.

Look through the headlines today, or follow the reception of recent works in the field, and potential points of intervention and debates already launched are everywhere. In the United States, for example, President Barack Obama's November decision to grant "deportation relief" to millions of illegal immigrants has revived a heated debate about American identity and obligation. From all across the political spectrum, commentators and activists put forward arguments about the role race does, does not, should, or should not play in American identity. The argument that many illegal immigrants have entered the country unfairly while tens of thousands of more "deserving" non-Latin American immigrants wait in line raises all sorts of questions about the shifting moral sentiments towards Latinos, Asians, and Europeans as "good" and "bad" future Americans. Even the counter-use of the the term "undocumented immigrant" as a term opposed to the more judgmental "illegal immigrant" reminds us of the entire regime of documentation that accompanies the immigration process in America today.

As global history at its best–and our guest to this edition of Global History Forum–reminds us, however, debates like these have a long history. More than that, debates like these are also inevitably entangled in networks of ideas that go beyond the nation-state itself. In his work to date, historian Robert Julio Decker, a scholar at the Technical University in Darmstadt, has explored the history of immigration regimes, while his future work promises to contribute the exploding literature on the history of capitalism. Speaking with him earlier this year during his tenure as a fellow at Harvard University, we discuss his path to global history, his early work, and his ongoing research on the global history of capitalism in the United States and the German Empire.

•

Born in the port of Bremerhaven, Germany, Decker encountered a German past that had global connections came early. While local fairs housed the usual assortment of Glühwein, Leberkäse, and Bratwurst, during his childhood visits to such events, Decker often encountered local American GIs who ran their own stand. Far from a provincial city in Lower Saxony, Bremerhaven was not just a port but also a node in Cold War military networks. But fascinated as Decker was with politics and history in school classes, teaching still tended to focus heavily on German national history. The focus lay on teaching the lessons of the National Socialist dictatorship, while after the fall of the Wall, history classes ended around 1989. German history, it seemed, was a reverse Sonderweg from dictatorship to normality. More interesting, at least in terms of pedagogy, was a special half-term course on the American Revolution. Following his graduation from high school, while working on a civilian service (Zivildienst) scheme with elderly people, Decker heard many stories about German encounters with the same American GIs that had populated the markets of his youth. This was interesting, but how to transform this interest into a career?

When Decker arrived in Cologne for university, he felt confident that he wanted to write history, but he also sought alternative subjects to the national history narrative he had received in school. He felt anchored in the modern period, but working on the history of the Third Reich seemed "too depressing, and there was too much to read." Fortunately, however, Decker had the fortune of encountering professor Norbert Finzsch, the former Director of the German Historical Institute in Washington who had worked on both German and American labor history. Finzsch's lectures imparted a sense of excitement: the narrative of the United States as a rising power and the rise of democracy (especially salient post-1945 German audiences) while integrating the complicated hierarchies of race, gender and class. Moreover, because of the strongly-established tradition of Latin American Studies in Cologne, students like Decker interested in U.S. history received a finer sense of the entanglement of U.S. history with its neighbors to the south.

As the end of his Master approached (with an end date in January, for bureaucratic reasons), Decker investigated the options for where to pursue a doctorate while also writing in English. Investigation suggested the University of Leeds, in the United Kingdom, as one option. There, scholars like Simon Hall and Kate Dossett formed an attractive team of advisers, also teaching a Master's program in Race and Resistance (with a focus on the United States). More than that, the PhD had the advantage of beginning, unusually, in March. Decker submitted his application materials, got in, and was soon boarding the plane, in 2008, to northern England.

Once at Leeds, Decker gained insights into the craft of history. If the lens offered in undergraduate course had too often been through a strictly national lens, at Leeds, in particular its Institute for Colonial Post-Colonial Studies, students re-interpreted British history through the lens of works like Marilyn Lake's Drawing the Global Colour Line, seeing empire less as a cosmopolis than as a tightly-regulated system of white and non-white spaces. Decker also mentions Erez Manela's The Wilsonian Moment and a workshop run by fellow Harvard historian Joyce Chaplin at the University of Sydney as crucial inspirations in shaping his historical vision towards the British and American past. An entire subfield on the making and maintenance of "white spaces" offered a way to re-interpret U.S. and Commonwealth History, and Decker wanted in on the conversation.

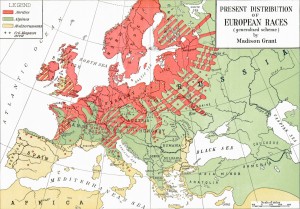

When the time came to choose his dissertation topic, then, Decker began working on the history of the Immigration Restriction League, a group founded in 1894 that sought to halt the then-growing numbers of immigrants from Eastern and Southeastern Europe to the United States. Not dissimilar from today's debates about Hispanic immigration, activists felt that the influx of not properly "white" immigrants threatened the integrity of the United States. They agitated not against immigration per se, but wanted to mold immigration patterns to embed America more in an acceptably "white" world of intercourse with "pure" Protestant Northern Europeans, not the predominantly Jewish, Catholic, and Orthodox who made up much of post-1890s U.S. immigration. In short, the IRL proposed nothing less than a massive restructuring of immigration law: not just Eastern Europeans, but also "imbeciles" and the "feeble-minded" were to be put under increased scrutiny. They proposed an "immigration duty" to be levied at Eastern ports that would then be used to beef up surveillance and guarding of the Mexican and Canadian borders. The League's greatest victory was the Immigration Act of 1917, passed against Woodrow Wilson's veto, which included many core IRL demands like literacy tests and a ban on "Asiatic" immigration.

Immersing himself in the IRL's archives (at Harvard's Houghton Library) as well as the "enormous" archives of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, however, Decker found that the story of the IRL was one about not just the development of the American state (think of the immigration duties being channeled to the Mexican frontier), but also about an international dialogue of whiteness that moved throughout the Anglosphere in the early twentieth century. Rather than finding patterns of American exceptionalism in the story of the IRL, Decker instead saw how fears of a "Yellow Peril" traveled nimbly across the Anglophone world. Take literacy tests, for example: tests that might have originally been devised in the Jim Crow South to block African-Americans from voting could then be taken up by IRL anti-immigration activists (the founders of the IRL were from New England). Once adapted to block Eastern European rather than black bodies, however, these laws had an afterlife, as administrations in places like Natal (South Africa) and Australia "perfected" them to control black, South Asian, and East Asian populations moving across the space where the Indian Ocean met the Angloworld. This adoption of the test then allowed IRL members to argue that it worked perfectly in other parts of the Anglosphere in protecting an assumed racial superiority.

Other global connections that Decker found in the archives were surprising: many of the IRL's American activists were opposed to white imperialism not for reasons of morality, but because they feared that empire too often provided an unintentional back door for non-white bodies to enter the metropole. Recall the fact that the period of the IRL's greatest strength was also one of American imperial conquest and expansion in the Caribbean and East Asia, and this view makes more sense. Asia and Latin America, these activists argued, had to be a space where American "financial missionaries" could invest and build up a benevolent empire of capital. Turning American overseas empire into a formal empire of settlement and more explicit population exchange threatened to throw the country, they argued, into turmoil.

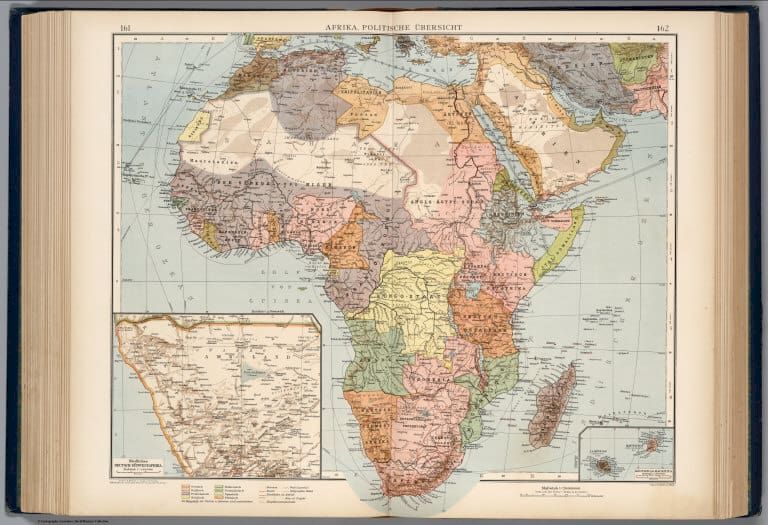

These were some of the ideas that Decker–by 2011 in Berlin, writing up his dissertation on a DAAD "returnee" scholarship for German academics–was putting to paper. By 2012, the dissertation was finished; since its completion, Decker has published several of his findings as articles and in edited collections. Decker secured a position at the Graduiertenkolleg Topologie der Technik (Graduate College for the Topology of Technology) at the Technical University of Darmstadt, a project founded in the wake of the "spatial turn" in historiography. For his Habilitation (a second dissertation required to obtain a professorial position in German academia), Decker wanted to combine his experience in American history with German history outside of the traditional national lens. He knew from his time in American archives that Washington's colonial experience had brought with it a huge boom in railroad building, whether in Panama or the Philippines. What if there was a similar story for the German Empire? Decker's initial enquiries led him to Namibia, or rather, as it was called as a German colony prior to 1915, German Southwest Africa. What could one learn by comparing the socio-economic spatial effects of railroad-building in multiple (German and American) peripheries?

In some regards, by approaching German imperial history from this perspective, Decker was challenging the old Sonderweg orthodoxy that he found so staid as a young student. Since, roughly, the mid-1990s, as part of a larger turn towards empire in the study of European history, scholars of Britain and France in particular, but also of Germany, had re-interpreted the way that the empire "there" reproduced itself "here" in the metropole. Some people might not even know that Imperial Germany had an overseas empire, but it did–Cameroon, Togo, Namibia, and Tanzania in Africa, plus several possessions in Oceania. Given the obvious centrality of the Holocaust and World War II to modern German history, however, scholars often drew a direct line between the German experience of colonial domination abroad (in Africa or Asia) and the later, Nazi-era experiment in colonizing Europeans. In less crude fashion, others argued for the belated formation of a German archive of colonial domination that could "travel" from Southwest Africa (where German occupation forces butchered close to 100,000 native Herero) to the Eastern fronts of the First and Second World War.

In his Habilitation, however, provisionally titled "A Global History of the Railways in the Colonial Spaces of the German Empire and the United States, 1884-1918," Decker seeks to re-interpret this history. The above narrative, he explains, looks all too much of the old Sonderweg dressed up in colonial garb. Based on his initial research in German archives, he explains, there's good evidence to suggest that German colonial administrators viewed themselves in an international imperial context; Spanish colonial mistakes in Cuba and the Philippines were studied with particular interest. None of this is to discount or hand-wave away German violence, but the point is that scholars need to speak–to use a computing metaphor–more in terms of a global "imperial cloud," rather than national Sonderwege where colonial history paradoxically feeds primarily into national history at home.

More broadly and fundamentally, however, Decker's new project stresses that, like its American counterpart, the German Southwest African story was "not just a military one. "This is," Decker explains, "a story of how to force people into a wage labor system." Lucky for Decker, then, that, in order develop the argument, he had the chance, still early in his research, to spend five months as one of the inaugural fellows at Harvard University's Weatherhead Initiative on Global History.

While there, Decker had the chance to participate in a scintillating seminar on global history with Professors Charles S. Maier and Sven Beckert, whose research on the global history of cotton held obvious lessons for Decker's work. For along with late 19th century colonial efforts to plant cotton in India, Togo, or Turkestan, the railroad was a crucial instrument in the re-ordering of a "global countryside." As Decker's research shows, not only did the penetration of railroads into the deep countryside of Southwest Africa or the Philippines wreck traditional local markets and integrate them into a global capitalist economy; more than that, the enlistment of native labor to build railroads themselves was itself a form of mobilizing and optimizing colonial land use. "This is really a story," Decker explains, "of the rise of population as a resource per se to be managed."

Where Decker's research promises to expand on the historiography of Imperial Germany is not just this history of capitalism approach gleaned from Beckert and fellow Harvard fellows Steven Serels and Norberto Ferreras, but also its comparative aspect. No mere colonial overlords obsessed with repression (recall the Spanish lessons), German railroad and agriculture experts were keen to learn from the British, Russian, French, and American experiences of how to combine capital investment, railroads, and colonialism. Decker is still early along in his research–he followed up his stay at Harvard with two months in Washington, D.C., to work more with the American colonial material–but it promises to offer a fine example of how one can globalize the study of national history.

Concluding our conversation, we ask Decker about the books that have inspired him most and that he would recommend to non-specialists on his own particular field. He lists three: Michael Adas'Dominance by Design, Andrew Zimmerman's Alabama to Africa, and the aforementioned book by Marilyn Lake and Henry Reynolds, Drawing the Global Colour Line. If Decker's initial research is any sign, not too long from now, future interviewees will be mentioning his work on railroads and imperial exchange as an inspirational work itself. We're delighted to feature him as our latest guest to the Global History Forum.