Is Global History Suitable for Undergraduates?

Cross-Posted on the Imperial and Global Forum

Last week, I came across two provocative blog posts, at The Junto and the Imperial and Global History Network (IGHN), on teaching global history that got me thinking reflectively about my own recent experiences of approaching American and British imperial history from a global historical perspective. The big takeaways from both pieces seem to be: 1) teaching global history is a challenge not just for students but for teachers; and 2) that the net positive from teaching history from a global vantage point at the graduate level far outweighs said challenges. However, The Junto's Jonathan Wilson concludes by quite explicitly questioning whether global historical approaches are in fact suitable for the first-year undergraduate classroom.

To start things off, Gemma Norman's post at IGHN outlines some fruitful experiences on the receiving end. Norman has just completed multiple graduate level global history courses that made

great use of what I would call 'global moments', citing an example of globalisation from a particular period in history and de-constructing it to show the components of globalisation. . . . As a teaching tool this was effective because by picking up an idea, person or movement at either the historical root or destination the student observed globalisation as a process.

Wilson at The Junto remains more critical following his first time teaching global history to undergraduates:

I had long been skeptical about global history as a standard survey course. It seemed too unwieldy, too shallow or spotty in coverage, and way too vulnerable to political ax-grinding. I assumed this course would reinforce old stereotypes: that history is an endless parade of random facts and dates and battles and names of elite men. Or else it would turn into pure theory, and thus an exercise in polemic. Either way, it would have little of the texture of lived experience, which is what I reckon makes history compelling to ordinary powerless students. After teaching a global history survey … I still pretty much think exactly that.

For Wilson 'the most important difficulty of the global history survey is about protagonists. Every remotely coherent history course, whether we consciously build it that way or not, is a narrative. Every narrative, whether explicitly or not, has protagonists who drive the plot and determine what subplots are relevant.'

He concludes with a double dose of optimism and pessimism:

So after a semester of teaching modern global history, what I really wish is that this course — or rather, a seminar on the same topic — had been part of my graduate training in United States history. In fact, if I ever have substantial influence over a program of study, I think it's one of the goals I'll pursue first. I would make modern global history a capstone course for the history major and a regular component in graduate coursework. But for first-year or out-of-major undergraduates? So far, I'd much rather start them off on the history of a town than of a planet.

Now I certainly agree with his call for a greater grounding in global approaches within graduate history training. Where we differ, however, is about whether or not global history courses are also suitable for first-year undergraduate surveys.

Over the past couple years, I experienced the challenge (and the pleasure) of teaching first-year undergraduate courses, one on America and the World (up to the First World War), and the other on the rise and fall of the British Empire (c. 1776-1946). Although not without imperfections, in both I utilized a global historical approach – and avoided leaving my students with little more than an 'endless parade' of names, dates, and battles.

Admittedly, I do recall having similar problems to those outlined by Wilson from my days as a high school student taking world history courses, with teachers using textbooks that aimed to cover just about everything without much depth, thereby leaving students with little but a limited understanding that lots of important things happened somewhere at some point in time — a problem that no doubt persists in some global history surveys and textbooks today.

Building from these experiences, however, and from having gone through a PhD program with a strong grounding in the history of imperialism and globalization, the key takeaway for me was to avoid teaching global history like I was taught world history, and to avoid using standard survey textbooks (Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days, for instance, worked quite well for exploring the leaps, bounds, and limitations of modern globalization).

Instead, I set both global history courses thematically, within a clearly delineated timeline. Focusing on the modern era, I first tied the courses to particular ideas that lay at the root of substantial political and ideological conflict throughout much of the globe. Indeed, so many of American and British global interactions have surrounded, or even been sparked by, politico-ideological battles over slavery and freedom (of people, taxation, and trade); nationalism and internationalism; or capitalism and socialism, to name but a few.

By approaching global history thematically, in both cases primarily as a global conflict of ideas, I (so far at least) managed to keep the material from becoming unwieldy. And by focusing on particular ideological conflicts that have appeared again and again throughout the longue duree of modern global history, the students time and again were able to encounter familiar thematic ideas even as they moved into potentially unfamiliar geographical, historiographical, or chronological terrain. The students were able to take away a deeper understanding of some of the great debates that dominated the modern world, as well as an introduction into how these debates took place across the globe owing in large part to the processes of modern globalization (increasing global integration and interconnectivity).

To return to another of Wilson's points of criticism, I would also suggest that within this framework there exists multiple ways of keeping one's protagonists, even in an undergraduate global history survey. For example, in the case of an early American history course, a local voice from within what would become a global slave system could be given through the narrative of an African's experiences from freedom to slavery, as in, say, Vincent Carretta's work on Olaudah Equiano.[1] Such a localized approach could also work when following the black loyalist diaspora during and after the American Revolution, borrowing from Maya Jasanoff's Liberty's Exiles. Or Linda Colley's The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh similarly could provide a female, protagonist-driven history of the global eighteenth century.

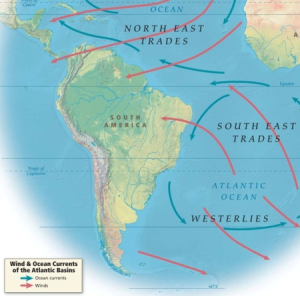

Regarding my first-year course on the rise and fall of the modern British Empire, I had my students begin by grappling with the rise of Free Trade England in the mid-nineteenth century. They first had to come to terms with the seemingly local conflicts over class, slavery, industrialization, and political economy that brought about this significant development in British history — a development that made free trade the orthodox ideology of the island nation for decades to come.[2] The students then had a local setting (take your pick of protagonists from among Chartists, aristocrats, the Anti-Corn-Law League, and suffragists) as a starting-off point to delve into the decidedly global political, racial, economic, and ideological conflict — from the often violent "opening" of east Asian markets, to the protracted politico-ideological battles between the Australian colonies of New South Wales and Victoria, to the global construction of the racial idea of Anglo-Saxonism — wrought by the expansion of British free trade and imperialism throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, a period that increasingly felt the pleasures, aches, and pains of modern globalization: from the wonders of global communications and transportation, to the problems of racism, nativism, and migration, to the horrors of global war.

This is not to suggest that I've 'figured it out' when it comes to teaching global history to the uninitiated undergraduate. Far from it. For instance, I readily admit that I could still do a better job of incorporating gender into both courses. But I would also note that the first-year students took to the 'global' with great alacrity, nor were they in the least bit put off by the long temporal and geographical trajectory of the courses.

As I continue to hone my global history courses, I will build upon these initial forays into teaching the global through the local and the ideological, and I will continue to incorporate fresh thematic approaches to the process. (Doubtless some will work better than others.) The publication of an ever growing number of accessible global histories, both from above and below, are making this ongoing experiment all the more feasible for undergraduate and graduate classrooms alike.

——–

[1] Vincent Carretta, The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings (2003); Unchained Voices: An Anthology of Black Authors in the English-Speaking World of the Eighteenth Century (2004).

[2] See, for example, A. C. Howe, Free Trade and Liberal England (1997); and F. Trentmann, Free Trade Nation (2008).