Reintegrating Apartheid into Post-War Global History: An Interview with Jamie Miller

In 1975, South African Prime Minister John Vorster met with Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda at Victoria Falls. The purpose of the meeting? To end white rule in Rhodesia.

This is not how we usually picture apartheid South Africa. But it sits at the heart of the story told by Jamie Miller in An African Volk: The Apartheid Regime and its Search for Survival (OUP, 2016). During an interview that lasted several hours, Miller spoke of the importance of taking self-conceptions of apartheid seriously, of historicizing decolonization in all its messy contradictions, and of the role of anticommunism in this history. He also elaborated on the process of writing the book: on his experiences interviewing former apartheid leaders and the ethics of entering the apartheid worldview.

Jamie Miller is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Pittsburgh. He holds a masters and doctorate from the University of Cambridge and has previously been a Fox Predoctoral International Fellow at Yale University, a Visiting Assistant Professor at Quinnipiac University, and a Postdoctoral Fellow at Cornell University. An African Volk is his first book.

—Aden Knaap

INTERVIEWER

The story you tell in this book didn't emerge until your second visit to South African archives. What was your original project and how did this new one crystallize?

JAMIE MILLER

It was originally conceptualized as a contest in southern Africa between different actors, each with conflicting ideas of the future. The focus was meant to be on that conflict, on those ideas, grounded in each actor's perspective on race and social organization. It was to be a multi-faceted story focusing on the 1970s and the end of the Portuguese Empire in southern Africa, an event which brought these different visions into tangible conflict.

That's not what happened because, as I was researching, I quickly found that for the most important actor in the story—the one that was most deeply invested in that future and had the capacity to influence that future the most in a geopolitical sense—namely, apartheid South Africa, there wasn't a sense of those ideas that was uniform and identifiable. In fact, those ideas were in marked flux. They were being vigorously contested by different power blocs within the regime at the political level, at the intellectual level. I quickly realized that actually this was the most important and exciting story to tell, because it went to the heart of how we think about apartheid in post-war history.

At the same time, there was another influence behind my thinking, which was that there's this really large amount of literature on the anti-apartheid movement, both in South Africa and externally, globally. I wanted to turn that story around: to ask how the architects of apartheid saw things. How did they understand the world's hostility to their program? Why did they think their vision for the future was not just feasible but even moral and just? Those were the questions that I thought would be historically fertile and original.

INTERVIEWER

For those who haven't yet read it, what is the book's main argument?

MILLER

The book tells the story of apartheid South Africa's response to what the regime saw as an existential crisis: that is, the emergence of the postcolonial world in the 1960s and 1970s. That world substantially defined itself against the National Party's apartheid program. Generally speaking, historians have seen South Africa's response to this existential threat as reactive, as about resisting decolonization, resisting African nationalism. I show that the architects of South African apartheid were looking to do something quite different. They were looking to coopt and invert and hijack the very norms and ideas that were being used against them on the global stage. It was an effort to rearticulate what it meant to be African in a way that included apartheid South Africa and thereby promote a fresh ideological basis for the regime's rule.

What this book does is to shows how that process took place both on the local and global levels. It takes the reader into the corridors of power of one of the most systematic, institutionalized, and bureaucratized systems of racial domination in history. It shows us, in their own words, how the architects of apartheid justified that system, how they processed the world's hostility to it and responded accordingly.

INTERVIEWER

How did the South African political elite respond to decolonization in the '60s and '70s? How can we group their visions for South Africa's future?

MILLER

There were basically three main visions of where the world was going, what the dominant drivers for geopolitical change were in the post-war world and how South Africa, the Afrikaner nation and the apartheid system fit into that. The first was associated with John Vorster (Prime Minister, 1966-78) and was very dominant in his small group of foreign policy allies. I term them the "doves." This was an idea that held that South Africa could find common interests even—indeed especially—with black South African countries, which would allow them to develop relationships and transform anti-apartheid hostility into friendship and mutual acceptance. From there, the logic went, the regime would have the security it needed, the breathing space, to bring "separate development" to fruition: to devolve power to the "homelands," the goal of which was to force particular political entities and structures onto black South Africans in such a way that the electoral roll for the central polity remained white. This was Hendrick Verwoerd's master plan of 1959 for South Africa's future. Vorster's vision of an African volk gained a lot of popularity in the late '60s and early '70s amongst the party, amongst the broader Afrikaner community, and amongst the white electorate as a whole, before imploding spectacularly in 1975-76.

The second plan was embodied by Vorster's Defence Minister P. W. Botha (later Prime Minister, then President, 1978-89) and was supported by his allies in the military and in parliament, especially in the Cape Caucus, which he headed. I term these guys the "hawks." Essentially, in the mid-1960s, beginning in the military, the military developed this idea that came to be known as the "total onslaught." The total onslaught was a doctrine that decreed that all anti-apartheid hostility—whether it was the same independent, post-colonial African governments that Vorster was wooing, or protesters on American university campuses, or Scandinavian governments—was a witting or unwitting tool of a vast communist conspiracy, orchestrated out of Moscow, and aimed at securing South Africa's riches, its wealth, its way of life, all for the communist cause. This was an idea that, as you can probably tell, was a bit way out there, particularly in its understanding of politics and ideas.

Its counterpart was this doctrine of "total strategy," which was also developed within the military. It was an idea that grew out of the writings of a few military theorists, particularly French and American ones who had been involved in colonial wars in Algeria and Indochina. The ideas was that if there was a total onslaught, a multifaceted attack on a particular regime—its way of life, the legitimacy of its rule, as was the case in colonialism as with apartheid South Africa—logically you needed a total strategy to fight it. That meant a plan that drew upon the country's psychological, financial, political, military resources, and more. In other words, it couldn't just be military. It had to be much, much broader than that.

These two ideas developed in tiny circles within the defense establishment. Nobody in the late 1960s would have believed that within a decade "total strategy" would be the blueprint for the regime's existence. In fact, nobody outside these circles even knew what these ideas meant. But almost as soon as P. W. Botha came into office as Prime Minister in 1978, he began to streamline the government and re-organize bureaucracies in line with the doctrine of total strategy. He began commissioning major reports about every policy area that South Africa had in light of total strategy. So these two ideas really came way out of left field and started to occupy a position of massive importance for the late apartheid state.

The third school of thought on how South Africa could navigate the emergence of the post-colonial world was essentially the verkrampte agenda. Basically, Afrikaaner politics is in this era was divided politically between verligtes and verkramptes. Verligtes are generally translated as "the enlightened." I don't like that translation very much, for obvious reasons. The verkramptes are often translated as "the narrow-minded" or "the bigoted." I don't like the latter translation either, because both of these visions were bigoted, by their very nature. The verligtes basically believed that, with some small adaptations, Verwoerd's separate development template could work, but it had to be updated to a changing world. The verkramptes really saw Verwoerd's template as gospel. Verwoerd's template was developed in 1959 as a deeply cynical program to deal with decolonization that involved minimal investment in the homelands, that even forbid private companies from investing in the homelands. They saw that template as unalterable in any circumstances. This position was infused with religious rhetoric and more than a few of the most influential verkramptes were leading members of the church. They argued that any of the things Vorster proposed—even small things like removing petty apartheid in creating integrated hotels or beaches, or working on an equal basis with black African leaders, having dinner with the President of Malawi, Hastings Banda (1961–94)—they said this was both against god's word and the thin edge on the wedge on the road to racial integration. They argued that if you said whites and blacks were equal on one level—if they could have dinner together, if they could go to the beach together—then how could you justify having separate political identities and rights and structures at all? There's a real truth to that central contention. One of the strangest parts of this story is the fact these verkramptes who stick their heads in the sand regarding what is going on in the world, who really are political "flat-earthers", that a lot of the things they say in the 1960s and 1970s end up coming to pass.

So, those are really the three schools that were contesting the shape of South Africa's future in this period. Outsiders saw a political party of extraordinary discipline and uniformity. But the reality was that behind the façade, the changes in global politics and life were creating deep and meaningful divisions between different blocs in the power structure.

INTERVIEWER

How did South Africa engage with other African polities in the 1960s and '70s? One might assume that South Africa would align itself with other white nationalist states like Rhodesia, while distancing itself from independent black states. But you tell a very different story.

MILLER

That's really a centerpiece of this book. In the early 1960s, when decolonization first unfolded, Afrikaners were terrified by what they saw. But by the late 1960s, that had changed. There was a real overconfidence, a delusion that separate development as a road map for South Africa's future could be rendered compatible with decolonization. What they decided to do was pursue something of a twin course of action, led by Vorster's government. On the one hand, the Nationalists reframed themselves as representing the Afrikaners as an African nation, articulating their legitimacy and their right to govern themselves in the exact same language and the exact same norms of nativist nationalism that other regimes were doing across the continent. This is a major shift in how we as historians understand how South Africa fits into African politics in this period. The regime was explicitly rejecting its colonialist and European heritage in an effort to rebrand itself in the language of decolonization. It was a claim to be fully African: the claim that just as Zambians get their country, and just as Ivorians get theirs, so too should the Afrikaners get theirs. The Europeanist discourses began to recede into the political background, and the racism, the political exclusion, the patronising, they all took on a new discursive foundation. This new identity drew upon older ideas of who Afrikaners were, emphasizing autochthonous concepts of belonging, and it surged into the political mainstream with real rapidity in the late 1960s.

The logic that came from this "realization" was that South Africa would therefore need to create relationships with independent African countries. South Africa began to reach out on the basis of three things. One, a belief in development and an ideological agenda of modernization, which will be very familiar, I think, to students of American theories of modernization and the intersection with race. The second was state sovereignty, the idea of the inviolability of the state, which served mutual interests for both the second generation of postcolonial African leaders and for the apartheid regime. And the third was anticommunism. This was perhaps the most important glue between the states that South Africa was able to reach out to. All of the states that South Africa developed relationships with—whether they were important trading relationships, or diplomatic and military quasi-alliances—they were all virulently anti-communist.

The other side of the coin was that if Afrikaners were going to define themselves as African, if they were going to argue that their claim to legitimacy rested on the same intellectual foundations as those of African postcolonial nation-states, then logically that claim to legitimacy couldn't rest on the same older languages that Rhodesian and South-West African whites used to claim their right to govern. One of the big shifts that happened in the late '60s and early '70s—and which was really pushed by Vorster and by columnists in major Afrikaans newspapers—was the idea that the Afrikaners were a national people and the Rhodesians and South-West Africans were not and therefore didn't have the same right to exist. That created a distance. It was a distance that a lot of South African voters found difficult to get their heads around, both because of heavily racialized social norms and because of the history of transnational whiteness in southern Africa. But it was a difference that matters a lot. That's the difference that pushed Vorster to suddenly start conversations about turning South-West Africa into an independent nation-state. That's the difference that pushed him to start distancing himself from Rhodesia and its Prime Minister, Ian Smith (1964–79). The rest of the world saw this monolithic white camp in Southern Africa, the "white redoubt". But the evidence shows something completely different. It shows really deep divisions between the elements of that redoubt. Vorster and Smith, for instance, had fundamentally different ideas of their political constituencies and the identity of that constituency, which you see when you begin to look at geopolitics through intellectual history. In fact, when you look into the documents themselves, the Portuguese, the South-West African whites, the Rhodesians, the Afrikaners, not only do they not identify with the same political languages as each other, but they condescend to each other. Behind closed doors, they think the others are quite backwards-thinking on race and social organisation. There is really no love lost between them.

INTERVIEWER

An ideological tension sits at the heart of your book. On the one hand, members of the Afrikaner elite are redefining South Africa as a postcolonial African nation. "When it comes to colonialism and fighting colonialism, we were the very first people to do just that," Vorster tells Zambian diplomats. On the other, they are promoting pan-white nationalism as a means of securing support from English-speaking white South Africans. What do you make of this tension?

MILLER

These ideological tensions are inherent in the apartheid regime and its vision for the future, and they're a really rich part of the history. I tell a story of the National Party embracing an Africanist nativism and explicitly rejecting its European heritage, which is a shift that takes place over the space of just a couple of years in the 1960s. Simultaneously, however, the Party is reaching out to English-speaking voters and articulating a pan-white nationalism. Those two ideas entail an obvious contradiction. But they're happening in the same people's speeches, they're appearing in the same election day pitches, they're happening parallel to each other. There's a lot of energy and intellectual resources put into reframing and in a sense recreating Afrikaner nationalism to give it this more Africanist identity, but its continually undercut by other intellectual trends and political impulses. To give an example, the regime at this time—late '60s, early '70s—is both starving the new homelands, making them incredibly dependent on the "central white polity," and simultaneously starting to pour large and increasing amounts of money and political capital into the homelands, and thinking about new ways to create jobs and industries there. Both of these policies are unfolding at the same time.

I'm not the first person to notice those contradictions, of course. But I think there's been a tendency to dismiss these as just contradictions, or bad policy, or weird non-sequiturs. I disagree. I think these contradictions both point us to really important diversity in the political thought of the regime and Afrikaner circles in general, and help us to explain seeming paradoxes in the regime's political program, which enrich our understanding. In this story, they help to explain how and why the regime bent over backwards to satisfy the demands of postcolonial black states, even at the cost of distancing itself from whites in Rhodesia and South-West Africa, who were their staunch allies. We need to embrace these paradoxes and contradictions and study them. I was really inspired by Louise White's recent book on Rhodesia—Unpopular Sovereignty: Rhodesian Independence and African Decolonization (University of Chicago Press, 2015)—which really grapples with the paradoxes of white Rhodesian identity, and is comfortable with them, and embraces them as paradoxes that are really central to the story. I feel very similarly about South Africa and Afrikaner politics during this era.

INTERVIEWER

How genuine was this self-understanding of the apartheid state as an African nativist state?

MILLER

I think you can see that clearly in two areas. The first is the way that the regime moved away from Rhodesia and South-West Africa in the 1970s. It basically sells its two most reliable allies down the river in pursuit of this new vision.

The other is that everyone involved in these conversations in Afrikaner politics knows what is at stake here. The verkramptes explicitly say, "we can see what you're doing here is rejecting our European heritage, you're rejecting our claim to be a bastion of European civilization in Africa in favor of a new language." That's one of the main causes for the verligte/verkrampte split. All of the trigger policies in that schism are about Afrikaner identity. In other words, if this was just re-branding, if this was cynical, if this was just a public relations exercise, it wouldn't have caused a schism within the ruling party, no more than it would have prompted the regime to abandon two of its very few allies. If it were just re-branding, those two things would not have happened.

Generally speaking, South Africa is seen as the holdout against decolonization; indeed, in some ways, the model against which decolonization is defined. In that vein, South Africanists have seen Verwoerd's "separate development" as a purely cynical device. Which it was. But others don't see it that way. If you look at newspaper opinion columns, if you look at the public sphere, if you look at the Broederbond records from the late 1960s, you see Afrikaner elites (verligtes specifically) seeing this as a real future for the Afrikaner nation. (The Broederbond was a secret society for Afrikaner elites.) The ability of Afrikaners to reject the claims of those who say they are depriving a future for other people in southern Africa—specifically black people—is said to lie in true separate development, in investment, in interdependence, in trade with the new polities. That's the political imaginary of apartheid. This is a world that exists in the Afrikaner political mind. This is a world that ignores forced removals. This is a world that ignores massive human deprivations. But it matters a lot. It matters because it drives different forms of politics and policy, across Southern Africa, for thirty years.

INTERVIEWER

What about the other side of the coin. How then did the leaders of postcolonial African states respond to South Africa's attempts to engage them?

MILLER

I really went back and forth on this. I think it's fair to say that the leaders who collaborated with Vorster's regime weren't going into this with their eyes closed. Hastings Banda, for example, worked on the mines in South Africa as a young man. They also knew what South Africa was doing in terms of trying to get public relations victories out of them. But they went along anyway. Banda delivered when he made a five day, red carpet, state visit to South Africa. Kenneth Kaunda delivered the meeting at Victoria Falls between the Rhodesian government and black nationalist leaders, with Vorster and Kaunda acting as mediators. They knew, and this was clear from the archives, that they'd be seen as selling the African National Congress and others down the river and they were OK with that. Politics is about choices, and they made those choices.

INTERVIEWER

I want to pose some more historiographical questions. First, what does attending to these paradoxes of decolonization do for how historians study the period?

MILLER

What it should do is make us look carefully at the intellectual content of these meetings between South Africa and post-colonial African states: those three pillars of development, inviolable state sovereignty and anti-communism provided plenty of common ground that these parties could meet on, not to mention the strong validation of Pretoria's nativist nationalism.

It should also make us look closely at the place and time. During this window of the late 1960s, early 1970s, the steam of decolonization had evaporated. The result was a real cynicism in Africa, with the centralization of power, authoritarian politics, personal enrichment, corruption, misrule, cynical ideologies. This window is really understudied I think—at least in terms of monographs. This is a period that has always been important for Africanists. We teach it in our survey courses. And for many it was personal. Many of the first generation of African historians found themselves deeply disillusioned by these governments and this cause of decolonization that they'd identified with. Suddenly decolonization was taking this terrible turn where leaders thought that validating South Africa and publicly being seen to do so was somehow in their interests. South African history is often thought of as an outlier, but this turn towards authoritarian, exclusionary, nativist politics does not come about because of unique political reasons. It comes about because the regime is explicitly looking to mimic what it sees as the political forms of post-colonial Africa. It is trying to fit in.

INTERVIEWER

Can you elaborate on the importance of anticommunism to your story? How does looking at domestic political contestations in the Global South complicate our understanding of the role of anticommunism in the Cold War?

MILLER

When you start to look at this story, you see a group of African states readily finding common ground in anticommunism. That is the major theme that infuses the transcripts of meetings between the South Africans and the Malawians, the Zambians, and so on. You start to see how anticommunism served similar interests in both places. It served to narrow the political space in each polity. It served to attach the legitimacy of the state to a language of much broader international, transcontinental legitimacy in ways that were antidemocratic and antipluralist. That's a really significant perspective, I think, because it points us into new ways of thinking about anticommunism as an ideology that is defined and refined by actors in the Global South precisely to do those things. This obviously builds on the trend to globalize the Cold War over the last decade, Arne Westad's Global Cold War (2005) being seminal in that regard. But I think this perspective should push us to go further. It pushes us to think about anticommunism as something that isn't only defined in Global North capitals. In this particular instance, the Americans are generally at their wit's end to understand how the South Africans wrap themselves in the blanket of anticommunism, which they are obviously possessive of. The South Africans, by contrast, think that anticommunism is as much their right to define as it is the Americans. I think as historians we should validate that and think about things through that lens.

The other thing that I think this story has really prompted me to think about is looking not just at a global story of the Cold War but looking at how geopolitics influences domestic politics. This has long been a trend in American history. Recently, East Asianists, East Africanists, and more have looked a lot at the ways in which the Cold War mobilized and influenced particular domestic agendas. But I think for South Africa this is a perspective that is so fruitful. Over time, anticommunism begins to bear a larger and larger ideological burden for the regime at home. It features more and more prominently in political speeches. There are institutes funded and set up in universities to study anticommunism, to study the total onslaught, out of all proportion to the merits of their intellectual output. I put this in a deliberately provocative way in a footnote in the book, which is the following: Basically the apartheid regime moves away from a purely Afrikaner national mission in the 1960s and 70s into one that also has room for English-speaking whites. In the 1980s, it moves away from the idea of a singular white polity. It explicitly acknowledges in its policies that it needs to foster a black middle class and to cultivate Indians and Cape Coloureds in a single political entity. Those are both things that in the 1950s would have been thought of as extreme transgressions of the gospel of what the Party's culture and norms and principles were all about. But the regime never—not even by a backbencher at some particular time in the course of forty years—exhibits anything but intense hostility for communism. That being the case, what did the regime ultimately stand for? To put it that way is, of course, a bit of a stretch. But it isn't a stretch to say that you can't tell the story of apartheid without the Cold War. That's to put the legitimacy and the ideology and the thinking of the regime in an ideological vacuum that is divorced from what is going on in the outside world, which is a mistake.

INTERVIEWER

How does your book, and the history of apartheid South Africa more generally, alter the history of decolonization?

MILLER

I think the story of decolonization and its relationship to apartheid needs to be told differently. The apartheid regime wasn't hell-bent on sustaining an intellectual framework of white hegemony defined against the concept of Africa. It was looking to do something completely different. It was looking to create a new model, an alternative model of postcolonial African identity. It was aiming to reach across the color line to lay an equal claim to the power and protection of African nativist nationalism. That's a big change to how we tell the story of decolonization and South Africa's relationship to it.

One of the other things this book is really doing is encouraging us to look at the fact that decolonization creates certain concepts that South Africa can invert, that it can coopt, that it can hijack. Decolonization creates ideas that South Africans are able to use—not with lasting success, but with some success in that place and time. This Africanization of Afrikaner nationalism doesn't happen in a vacuum. It's part of a process that happens right across the Global South. If you read James Brennan, if you read way back to Ben Kiernan, If you read Gerard Prunier, it's so much more productive to think about decolonization as a process that doesn't transfer power from Europe to the local. Rather, it's this massive all-in brawl on the ground between different political movements, both in the pre-decolonization and immediate post-decolonization moment, to try to see which political party, which movement can articulate that it can lay claim to the mantle of nativism, that it can say we avoided being here therefore we ought to have the right to rule and we ought to inherit the apparatus of the colonial state. This is happening in South Africa precisely because that is the dominant model of global south politics at the time. Nationalist leaders aren't suddenly reaching for authoritarian nativism for no reason. So in our lectures I think we should be talking about these different chapters in the same story, rather than the way we tend to treat decolonization and South African history as two different books in two different areas of the library.

INTERVIEWER

You conducted more than fifty hours of interviews for the book. How was oral history important to your project?

MILLER

In a lot of the history on this era, the main historical actors appear quite two-dimensional. That's dangerous because when actors stop being perceptible as people, you can't get inside what they're thinking, how they're thinking. Their politics become abstract. They become just names on a page. You can't achieve historical empathy.

This problem was something I really wrestled with in the middle of the project and I tried to tackle it in two directions. The first was that I'd been working in a lot of big state archival collections and the actors weren't becoming well fleshed out in my writing. So, I started to look more assiduously at archives that could tell me about how individuals within the political structure were thinking about the future, about their identity and about the political world behind closed doors. This meant the caucus minutes of the National Party, which show how the caucus was speaking in private without any reporters and without an audience. It also meant going to the Broederbond archives. The archives are contained underneath the Voortrekker monument: the imposing structure that sits just to the south of Pretoria. They show what these elites were talking about, what types of concepts they were using, how they understood these concepts and what the line coming down from the executive council of the Broederbond was on particular issues. They reveal depth and texture, debate and contest.

That was one way I tried to flesh out my actors. The other part was the oral history—the interviews I conducted with former officials from across the regime: politicians, diplomats, spies, generals, and a lot of other off-the-record conversations. This was really challenging because, when you're sitting opposite the person in the interview, you have to convey both historical empathy and critical thinking. You have to filter out their self-justification, which is sometimes very strong in the post-apartheid era. On the other hand, a key pillar of the book was to really understand the world of Afrikaner political thought as the actors in the story did, rather than as I or my readers might today. Many of these individuals still inhabit that same conceptual space. They still believe in the same things and concepts that they did in the '70s. Certainly, when they're recollecting their experiences during the '70s, they're taken back to that universe. So talking to them was a really useful way to understand those perspectives and in a sense "translate" them into a more universalist political language that we are more familiar with and into a language that I could use to tell the story to my audience. In this sense, the oral history was not only about recollections and events and research leads. It was about using the interviewees to transport me into the intellectual universe that I needed to travel into to tell the story, to understand what was going on.

INTERVIEWER

What was it like carrying out these interviews? What kind of training did you have, and what did you do to prepare beforehand?

MILLER

There was a lot of learning on the job. It was about coming in with specific questions and often specific documents—I'd usually print out particular documents that the person had written or that I'd gotten from their files so they could read them. That helped transport them back into the past. A lot of these people have had to reinvent their pasts, both publicly and perhaps privately, since the end of apartheid. They were associated with something that almost the entire world sees as something to be utterly rejected, a crime against humanity, and they have had to justify to themselves what those decades of their life were spent defending. I needed those documents to fracture that façade.

The other thing I really hadn't expected was that when I spoke to other people in my field it became apparent that being a man and being a foreigner—a non-South African—was helpful. I could tell when I was interviewing people that they felt comfortable opening up to me because they felt I wasn't quite part of the world that they've been through for the past twenty years of condemning everything that they've been part of. I was an other. The natural affinity between Australians and South Africans also helped to break the ice. Just being a man was also a huge advantage. I wouldn't underplay the patriarchal aspect. The world of Afrikaner life and politics during this era was deeply patriarchal. Not a single woman ever represented the National Party in Parliament. Ultimately, you need to find whatever way you can outside of the intellectual to connect with your subjects, I suppose.

INTERVIEWER

How did you decide who to interview?

MILLER

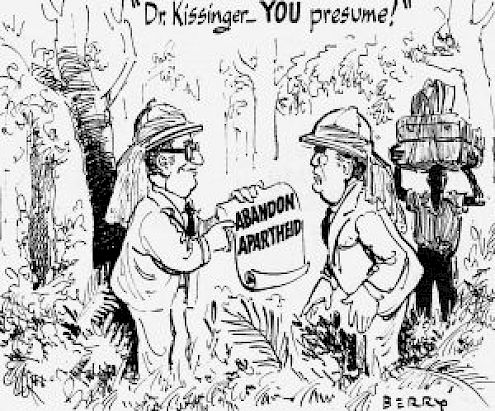

I tried to interview everybody that I thought would be pertinent, that appeared in the archives, and who I heard about from other scholars. What was interesting was that almost everyone who was involved in my story from the South African side was keen to talk. They were really interested that someone was showing interest in this chapter of their lives. But the people from the other side weren't—the people who were validating the apartheid regime, who were giving it public relations victories, who were in a lot of ways selling out the anti-apartheid struggle during this time. Not just Henry Kissinger but also Zambia's President, Kenneth Kaunda, and Vice President Mark Chona. They're all alive, they all grant interviews to other people. But surprise, surprise, they weren't so keen to talk to me about my story. It's a chapter of their lives that they would prefer no one was talking about.

INTERVIEWER

Where does your book's argument sit within popular understandings of apartheid's history in South Africa today?

MILLER

The vantage point the book takes in talking about the apartheid regime is not one that is readily situated in a discourse of wide currency in the public sphere in South Africa today. The debates in the public sphere about apartheid and about the apartheid regime are fraught, but they're generally ahistorical and politicized. That is a big problem. I don't want to simplify matters, but it is generally the case that a lot of white South Africans don't want to talk about that past and therefore don't want to access that history. It is also the case that there are political forums like AfriForum and Solidariteit who spend their time reproducing versions of apartheid-era myths to continue to justify what are essentially racist and nationalist policies in favor of Afrikaner people at the expense of other people. It is also true that there are other institutions, political actors, and people who prefer to keep "apartheid" as a political weapon, and therefore promote some channels of inquiry and steer clear of others. This is really a society that has not come to terms with its past at all. That's a shame because there are so many great historians in South Africa doing extraordinary work. South African history is, I would say, the deepest, most varied, most wide-ranging historiography in all of African history. But it's that inability of the public sphere to take that seriously that's a big problem. After all, none of what I talk about in the book is really ancient history. It's stuff that really matters today.

INTERVIEWER

Ethically, what does it mean to study South African history from the perspective of the apartheid regime itself? In privileging that perspective, is there a way in which black South Africans are pushed to the peripheries of the text?

MILLER

I've spent a lot of time thinking about this and I always seem to come to the same point, which is this. Our understanding of the apartheid regime is, in some important respects, really quite limited. What we do know, and teach, is full of contradictions and gaps, that we as scholars know to exist and that have not been fully explored. So I think there are two options here. Either we put our heads in the sand and don't engage with the regime seriously, in which case we neglect our duties as a scholarly community. Saul Dubow makes the point in his recent book that this is largely, in fact, what we as South Africanists have been doing. Or we do the job that a historian has to do which is to be detail-oriented, frank, fearless, and look at the full picture of why the apartheid regime evolved as it did and what that phenomenon entailed. To do that we need a much better understanding of the politics, ideas, economics, science, and culture of the regime—and much more. Moreover, I ultimately think that studying the regime, explaining the intellectual content that drove that system, that was the engine for all that human suffering, helps us to contextualize and historicize that human suffering more.

INTERVIEWER

What do you see as the future of South African history?

MILLER

I wish I'd said this more explicitly in the book, but basically I'm trying to set out a different path for how we study the apartheid regime. One of the big things this book does is it looks to broaden and deepen and historicize the intellectual content behind the apartheid regime. I believe we need to take Afrikaner nationalists and their ideas seriously. We can't simply adopt external perspectives, and we shouldn't be thinking about the regime solely in terms of violence or force or corruption, because that perspective can't explain a lot of the complexity in the political history of this era. It also can't explain a lot of the paradoxes and contradictions that we've talked about today.

Another thing the book does is it really tries to look at the support of non-racist political ideas for racist political projects, as well as how racist ideas are channelled through and intersect with other concepts. There's a lot of this going on, even in the "progressive" fringes of Afrikanerdom during this time, ideas like anti-communism, development, self-determination. These are extremely influential for the highly educated powerbrokers of this era, the verligtes who think of themselves as forward-looking, but whose ideas are twisted to serve political ends that are deeply racist. I know there are global historians writing histories of self-determination and so on, and the South African experience is an important exemplar of how these ideas can be utilized in extremely oppressive ways.

A third aspect of this new approach is that I really take a cue from the linguistic turn. I was very influenced by Susan Pedersen's chapter in What is History Now? (2002)—which is now fifteen years old—and her call to focus on discourse and political imaginary as the central medium of politics. The field is still dominated by old structuralists and liberal approaches in how we tell the story of apartheid, though most historians I know are very keen to move beyond these. I think discourse is a much more productive avenue here. A whole generation of Afrikaner opinionmakers, policymakers, and powerbrokers believed that separate development was the future, that it was the panacea for the Afrikaner nation's (and South Africa's, in that order) woes. The fact this was a delusion, the fact that this ignored the brutal human cost, the fact that they came to this opinion only by silencing and rejecting the input of all sorts of other voices, none of this mitigates the depth and breadth of that belief. That political imaginary—that image of what was happening in South Africa and what the future would look like—was an extremely powerful shaper of politics and ideas in this era, probably much more so than what was actually happening on the ground. If we ignore that image and the language in which it was constructed, we shut ourselves off from so much. We make it really difficult for us to understand where these people are coming from and to tell their stories in a historically faithful way.

The final thing that this book hopefully does for southern Africanists is that it suggests we need to see apartheid in the context of contemporary events, contemporary forms of power, contemporary ideas. There's a real tendency to see apartheid as a strange anachronism, as a holdover. But there are lots of ideas that are distinctly modern about it. It doesn't exist in the past, it exists in the post-war era. We need to place apartheid in its place and time, to show its support structure in ideas with global resonance. South Africanists are very involved in global history at the moment, and I find that movement inspirational in my own area. After all, one of the key reasons why a system that was so dysfunctional, so lacking in external support and validation, lasted for so long was because it was able to find intellectual support in broader ideas like anticommunism, like development and materialism. These things matter a great deal and I think we need to take them into account.

INTERVIEWER

And what about the future of international history?

MILLER

I think there's a real disjuncture between the work that is being done in this field which is truly global and the fact that a lot of the institutions in the field are still very America-centric. When I think about really good international histories that I've read over the last couple of years, I think of work by people like Natasha Telepneva, Tanya Harmer, Artemy Kalinovsky, Nat Powell, and so on. A lot of these historians are younger, many of them are based in Europe. Much of this generation has come of age at the tail end or even after American unipolarity, with Iraq and everything, so it's only natural that when they read global history they read it in a way that America is just one of many actors, and not necessarily the most interesting or relevant one. If you look at the output of things like H-Diplo, for example, they're already publishing roundtables for books that are not America-centric at all. I think it's inevitable that in the next few years we'll see a new society created for international history in the broader sense, not just postwar, and I think it will probably come out of Europe. It'll be really interesting to see how the more traditional, America-centric organizations respond to that challenge. How that process unfolds will probably have a big influence on how the discipline and the subfield develops.