January 2024: What We’re Reading

Matilde Cazzola, Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory.

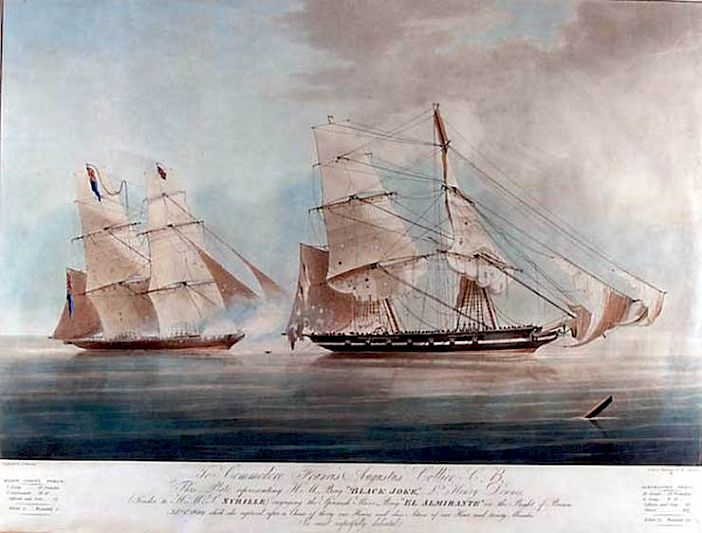

Maeve Ryan’s book explores the “humanitarian” strategies implemented by imperial Britain to govern and employ the nearly two hundred thousand formerly enslaved Africans that the Royal Navy’s “slave squadron” re-captured and liberated as it seized hundreds of illegally operating slave ships along the West Coast of Africa between 1808 and 1867. Resettling them as free settlers in Sierra Leone and Cape Colony as well as the West Indies, Brazil, and Cuba, the British imperial authorities employed a discourse of philanthropy to justify and support the implementation of policies of social control on people expected to repay the “debt” of their salvation. The book is a brilliant example of the richness of the growing strand of historical research studying the entanglements between humanitarian and imperial policies.

Reeju Ray’s new book shows how the “making” of places and peoples is a crucial part of imperial governance through the analysis of a fascinating case study: the “hills” and “tribes” which were constituted by the British conquerors and administrators along the frontier of the Himalayan borderland since the mid-eighteenth century. As the book demonstrates, the law was the fundamental strategy that the British primarily used in order to extend the frontier in North-East India and establish their control over geography as well as resources, people, and their labour. By combining different methodological perspectives with meticulously researched archival findings, Ray’s work is an original and important contribution to British imperial history, legal history, and the scholarship on spatiality.

In this interview with Mauro Boarelli, Carlo Ginzburg interrogates the problem of the fabrication of news to be insidiously used for political purposes. While the dissemination of rumours, fakes, and conspiracy theories is unfortunately an “old story” in human history, today’s technological progress alters the scale and implications of this century-old phenomenon. In this conversation, Ginzburg especially focuses on the social predisposition which makes specific groups of people particularly prone to become the victims and targets of the spread of fake news, subsequently fomenting their further circulation. In the digital era, he suggests, it is only the promotion of “digital philology” which can help societies resist, and combat, fake news.

Asensio Robles López, EUI, History Department.

There are not many authors whose first book has had the impact of Daniel J. Sargent's A Superpower Transformed. This book is not just another work on U.S. foreign relations. It is one of the latest (and best) contributions to the growing field now known as "America in the World.” A Superpower Transformed not only makes us think about U.S. foreign policy and the many challenges it faced during the turbulent 1970s. More importantly, it makes a compelling case that it was the international arena of the 1970s that changed the rules of American superpower, not the other way around. "The 1970s did more to the United States than the United States did to the world in the 1970s," is Sargent's bottom line.

At the heart of this argument are the concepts of the post-1945 US superpower and the impossibility of sustaining it in an increasingly globalized world. Herein lies a second strength of the book. A Superpower Transformed situates the United States within the multiple dynamics of the 1970s while recognizing the transformative role of transnational actors. Sargent's examination of the collapse of the Bretton Woods system is a representative case in point. One of the key problems in maintaining the dollar-gold convertibility window was the inability of American policymakers (or any national government, for that matter) to control international finance (especially the Eurodollar markets) and its destabilizing actions since the 1960s.