The Sino-Soviet Split and the Left as Global History: An Interview with Jeremy Friedman

Among the crimes cartographical and otherwise perpetrated by the Mercator projection, the Cold War projection of an Asia dominated by the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China numbers among the most egregious. Famous for inflating land areas the further away they were from the Equator, when applied to the world of the early 1950s, the map projection made it seem as if the Communist world was monolithic. The greater part of Asia was covered with red ink, while the freedom-loving (and less cartographically distorted) blue fields of the earth shrunk before the grim crimson blob stretching from Berlin to Vietnam.

Of course, the "Communist world" was never as unified and cohesive as the mapmakers suggested. While the Soviet vision of proletarian workers unifying to overthrow capitalist oppressors and the Maoist vision of peasant armies challenging imperialists from from Hanoi to Havana seemed to march in lockstep to Cold Warriors, by the early 1960s, the two socialist powers came to irreconcilable differences. Soviet advisers were expelled from Beijing as Chinese leaders castigated the Soviets for making peace with the imperialist Americans; Soviet leaders denounced Mao as a revisionist and a nationalist.

But the Sino-Soviet Split, as it is called in English and Russian ("Sino-Soviet Hostility" in Chinese – zhōng sū jiāo'è), had ramifications that went far beyond the oceans of red dye spilled by the Mercator projections. As country after country "the Third World" gained independence, the Soviets and the Chinese were among the few major powers that offered compelling developmental – and historical narratives – to fledgling nations. But what would the meaning of Revolution be in a decolonizing world? Was Revolution really about anti-capitalism, as the Soviets argued? Or was the real essence of Revolution opposition to empire, as their Chinese rivals put forward? How did the Chinese challenge affect the Soviet outreach to the Third World, and vice-versa? And what was the effect of the Sino-Soviet Split on the intellectual repertoire of a global Left?

These are among just some of the questions at the heart of the work of Dr. Jeremy Friedman, our guest in this latest installment of the Global History Forum. Friedman, the Associate Director of the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy at Yale University, is the author of the forthcoming Shadow Cold War, scheduled to appear with the University of North Carolina Press next year, in 2015. Global History Forum spoke with Jeremy recently to discuss his intellectual journey thus far, the book, and a forthcoming project on the history of the Third World.

We start with his undergraduate years. Friedman arrived as a freshman at Stanford interested less in history of the Soviet Union or Maoism than German philosophy. Having spent a year devoted to talmudic study at a yeshiva in Baltimore, Friedman entered Stanford with a strong command of German. That encouraged him to explore the history of continental philosophy seriously and early with professors in Stanford's Philosophy Department. He took courses on Kant, and considered majoring in philosophy (which he did, albeit as a double major with history). But Friedman felt that he wanted to write for a wider audience than an academic career in philosophy might allow. He had begun to study Russian and was taken by undergraduate and graduate seminars on Soviet history with History professor Amir Weiner. The Soviet experience seemed like the purest attempt to translate Marxism - a major expression in the German philosophical tradition - into political practice. The experiment in transforming ideas into statehood demanded explanation.

Friedman dipped his head further in the direction of things Soviet. An internship at the US Embassy in Kiev allowed him to perfect his command of the language. After exploring the USSR's relationship with the European student movements of the 1960s in graduate seminars, he wanted to go further. He applied to top graduate programs, and was admitted to Princeton, where he headed directly from Palo Alto to work with Stephen Kotkin. But rather than merely doubling down on things Soviet, Friedman began to take courses in Chinese at Princeton, motivated, he explains, by an interest in using the Sino-Soviet Split as an episode to probe the ideological differences in Marxism's twentieth century trajectory . "The Soviet Union seemed, after the Second World War, to represent the Catholic Church in the Marxist world. It was the orthodoxy," Friedman explained. "Mao became the Luther, the Protestant Reformation of this moment." It was a clash of ideas – and foreign policies – that demanded explanation.

As he thought of how to transform these intuitions into an actual project, Friedman highlights, friendships and prior training came in handy. Life in leafy, suburban Princeton was buoyed by friendships with other then-graduate students like Jack Tannous, Friedman's roommate and now an assistant professor of Late Antiquity and the Eastern Mediterranean at Princeton itself. Almost as important were the lessons philosophy had imparted. When historians complain that outsiders don't read them enough, or about the obsession with causal relationships that defines some social science disciplines today, Friedman notes, they might do well to think about what philosophers call "INUS" conditions. These are "insufficient but necessary parts of a condition which is itself unnecessary but sufficient for the occurrence of the effect."

At stake here is what historians mean when they talk about causality. Consider what historians might usually diagnose as the causes for the First World War: an Archduke in Sarajevo, German battleships, European mobilization schedules and trains, the hyper-masculine and bellicose culture of contemporary European statesmen – the list goes on and on. Together, these conditions were obviously sufficient for war to start - war did start, after all. But we can't say that they were necessary for war to start. It's easy to imagine how, hypothetically, the assassination of King George V or Nicholas II could have also started a war. Among the collection of conditions itself, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand's being in Sarajevo is an insufficient cause for war, since the mere fact of Franz Ferdinand being there didn't cause the war. It was, however, a necessary part of the general European condition that was itself unnecessary for war.

Here's the point: too often, historians obsess over "causes" when they're really talking about INUS conditions. It's important to do the hard empirical work to reconstruct events like the circumstances of the Archduke's visit to Sarajevo; without a Rankean grasp of history "as it actually was," historians can't determine whether a single condition was a necessary condition for the effect in question. But having established the facts of the case as best as we can, smart history means less obsessing over what "the" one INUS condition was that caused something – there won't be one. It demands pondering how a collection of INUS conditions did become sufficient to start events, just as other collections of conditions might not be sufficient.

Friedman's training in philosophy, language, and history was beginning to pay off. Close to completing general examinations in his second year at Princeton, Friedman submitted to Kotkin what he jokingly recalls as perhaps the most over-ambitious dissertation prospectus in the history of the Princeton History Department. Not merely content to analyze the Sino-Soviet Split, Friedman wanted to author a global history of the Left. He had a tripartite scheme in mind: the Sino-Soviet story, the history of the Left in the Third World (learning Vietnamese was mooted at one point), and the history of the New Left in the West. "Maybe [Kotkin] was just giving me enough rope to hang myself with," jokes Friedman. But the prospectus was approved. It was time to translate years of hard-won language work (Russian, German, Chinese, and Hebrew, plus some Spanish and Portuguese) into time in the archives. Packed, prepared, and excited, Friedman booked his tickets for Moscow and Beijing.

He did so at a felicitous time. Outsiders often imagine the archives of these two Communist superpowers - one former, one current - as foreboding and closed to outsiders. But Friedman arrived in the two capitals at a time when openings in certain archives allowed him to reconstruct relations between the two powers to an unprecedented level of detail. In Moscow, while some estimate that up to 90% of the holdings of the former Communist Party Archive for files after 1953 remain off-limits, the archives for the Soviet Foreign Ministry were more open. (The archives of the KGB are open in some of the Baltic Republics, but the central archives in Moscow, alas, remain closed to researchers.) Still, Friedman trawled through reams of Russian-language diplomatic correspondence not only on China, but also on the Third World countries in which the two battled for influence. A picture was beginning to emerge.

But the Aeroflot boarding call to Beijing soon called. Friedman worked in the state archives of the Chinese capital in the late 2000s, a time at which the Chinese Foreign Ministry was declassifying records in tranches: up to 1960 one year, to 1965 the next year, and so on. Thanks to these measures, Friedman was able to follow Chinese foreign policy through 1965. (Unfortunately, since the time of Friedman's research, a massive curtailing on access has been afoot. The number of open documents declined from some 80,000 to 8,000 today. Some speculate that the troubles over the South China Sea, and the possibility that documents on relations with Vietnam or other neighboring maritime countries could inadvertently be unearthed, play a role). The Chinese temporal limits and the gaps in the Russian archival record posed some problems, but by traveling to Berlin, Bucharest, and Belgrade, Friedman was able to reconstruct parts of the diplomatic traffic zipping back and forth across the world during the 1960s and 1970s. (Much of the East Germans' diplomatic traffic with their Soviet patrons is open, at least until the early 1980s, while the Romanians maintained ties with China at a time when the Eastern Bloc grew estranged from Mao.)

Having assembled it all, first as a dissertation and now as a book, what did he find? Friedman argues that the best way to understand the Sino-Soviet Split is less in terms of personal clashes between Mao and Khrushchëv, or even "objective" differences of geopolitical interest, but rather a fundamental difference in the two countries' concept of what Revolution meant. For the Soviet Union, Friedman argues, "Revolution" was fundamentally about rolling back capitalism. A superpower originally oriented above all towards Europe – Germany in particular – the Soviet Union envisioned that Revolution would come about through muscled proletarians overthrowing their portly industrialist masters. Even if the territories of the former Russian Empire themselves scarcely resembled the factories of Manchester or the Ruhr that Marx and Engels had analyzed, the Soviet project embodied a vision of human progress that saw the social question being resolved through people and nations becoming productive industrial workers. Visit sites like the coal mines of eastern Ukraine or the gargantuan aluminum factory in southern Tajikistan, and you can still the shrines to this once powerful ideology.

The Chinese started from different assumptions. For much of its 19th and 20th existence as a state, Russia had expanded and expanded; China, in contrast, was carved up by foreigners. Whereas Stalin's Soviet Union had made up much of the gap in industrial output relative to rich Western countries by the dawn of war with Hitler, the China that Mao and other Communists inherited in 1949 was clearly much, much poorer than the Western powers that had long dominated it. Further, whereas the Soviet Union had been established in a world where the British and French Empires controlled the greatest extent of territory ever, the PRC was established just as colonial empires were winding up their own territories. By the 1960s, Africa was rapidly decolonizing. But many of these independent states still remained obviously dependent on former colonial masters. Imperialism, not exploitative capitalism, became the core enemy in the Maoist diagnosis of global injustice. Even as Moscow and Beijing appeared united throughout the 1950s, an important ideological difference festered.

This clash of ideologies – and, Friedman emphasizes, difference of positions within the international system of the day – soon led to a traumatic split. In places like Guinea, Moscow provided large amounts of aid designed to furnish post-colonial countries with a working class that could eventually be organized into Communist Parties. It encouraged African leaders not to expropriate the European corporations that continued to extract value from national territory. Expertise - even if European - was crucial to industrial development and the formation of a working class. But often, ruling dictators in these countries thought not in terms of effect of the establishment of class difference but in terms of an anti-imperialist national struggle that would erase all difference. The Guinean regime kicked out Moscow's Ambassador, complained about the "lavish" living standards of Soviet advisers, and later accepted Chinese aid. Maoism, for many countries, offered a vision of subaltern globalism, revolt against white Europeans and Americans who had exploited them. Moscow's plan for getting the economics of the Third World right sans political domination had failed.

The politics grew worse for Khrushchëv and Co. Isolated from the United Nations and the international system, China could kick up dirt from Formosa to the Himalayas and even embraced the idea that global nuclear war was inevitable. Moscow had more serious gains to hold onto. Whereas it had once been happy to support anti-imperial revolutionaries from Cuba to Egypt, the Soviet Union's brush with annihilation during the Cuban Missile Crisis led it to place an emphasis on achieving peaceful coexistence with the United States. Beijing responded by tarring the Soviets as status quo white imperialists, different only in style from the British, French, or Americans. Moscow denounced Beijing, dispatched ever more aid to Third World allies (Vietnam in particular), and played up its "Eurasian" credentials by sending Central Asian emissaries into the world and inviting Africans and Asians to marvel at cities like Baku and Tashkent. Still, the optics of "white Russians" betraying dark-skinned revolutionaries were devastating. Worse, as Beijing fomented dissent within the Left, a wave of military coups in geopolitically significant countries like Brazil (1964), Indonesia (1965-66), Ghana (1966), and Mali (1968) limited the number of available Third World arenas for Leftist political confrontation.

Friedman's Chinese source material ends at around this point in the narrative – around 1965, with the Chinese seemingly having eaten the Soviets' lunch – but he narrates the ironic result of this struggle with skill. After a period of diplomatic isolation during the Cultural Revolution (almost all Chinese Ambassadors were recalled for "re-education") when Moscow seemed to have won the conflict by default, China re-emerged on the global scene with a second aggressive wave of delegitimization campaigns against the Soviet agenda for the "Third World." (Indeed, terms were important: for the Soviets, the world was divided into the binary struggle of the capitalist world against the socialist world, not a tripartite division according to wealth or colonialism.) And after Nixon traveled to China, Beijing possessed new arenas through which to battle it out with the Soviets. One was an emerging condominium of power with the United States, consolidated in particular under the Carter and Reagan Administrations, that lent nuclear-armed China additional clout in pushing back against the Soviet Union to its north and pressuring Vietnam to its south. On a global scale, moreover, Beijing felt empowered to attack Moscow's clients around the world (the MPLA in Angola, the Vietnamese in Southeast Asia, and, later, the PDPA in Afghanistan).

The second was the United Nations, where China took over Taiwan's Security Council Seat in 1971. There, China supported the emergent "subaltern nationalism" of the New International Economic Order and sought to present itself as the natural leader of a "Global South" or "Third World." The terms may sound innocuous today, but to Soviet ears they threatened to divide the world not between exploited workers and capitalist masters (with the USSR leading the former camp) but between contented, non-revolutionary white bourgeois "Northerners" and black, brown, and yellow "Southerners" represented by parties like Julius Nyerere, Fidel Castro, and Mao. Able to persecute Soviet "hegemonism" now not only in Third World associations in obscure African capitals but now, also, the "Third World debating society" of the General Assembly, the Chinese quest to tar the Soviet anti-capitalist Left as status quo, white, and imperialist gained further momentum.

And yet from a certain point of view, nothing had changed. China had always been anti-imperialist. The threat now, however, was Soviet hegemonism, not the British or French. Maoism turned out to be only the most suitable vehicle for Chinese anti-imperialism at a particular stage in history. The Chinese, who once prided themselves on being more revolutionary than their brothers in arms, began to embrace capitalism. by the 1980s, however, foreign investment and a slow "peaceful rise" within the bounds of US hegemony provided the best solution. Anti-imperialism and the Chinese national interest had always been the key goals - so what if they now demanded alliance with (American) white imperialists and the transformation of China into a giant link at the bottom of a global capitalist value chain?

Moscow pushed back by throwing its hat in with a new bench of clients. Some were formal allies, like India, Iraq, and Vietnam. But a flood of belated revolutions across the Third World and the collapse of Portuguese colonialism blessed Moscow with a new bench of subaltern allies: Somalia (until 1977), Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan. As Friedman explains, this was an ironic turn. To a very large extent, Moscow ended up inheriting Beijing's old anti-colonial allegiances and rhetoric, but it was still committed to an anti-capitalist program of revolutionary change. Yet promoting anti-capitalism had been one thing when Moscow's allies were in Prague, Warsaw, and Budapest. It was another thing entirely when they were in Luanda, Addis Ababa, and Kabul. And the ideological policy tack made it difficult to make objective diagnoses about the character of Revolution in more geopolitically critical countries, like Iran.

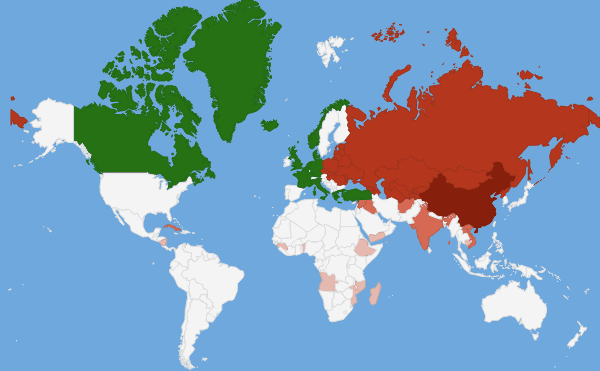

The race for global power, c. the late 1970s; green indicates United States and NATO allies; light red Soviet Union, Warsaw Pact, and Friendship Treaty Allies; dark Red the People's Republic of China. Pink indicates "states of socialist orientation" deemed by Moscow to tack sufficiently left to warrant expanded relations. Whereas China had actively courted Left-leaning partners in the mid-1960s, by death of Mao, in 1976, it had largely withdrawn from the game of Third World influence.

A wave of disasters costly in terms of rubles, lives, and legitimacy followed, the war in Afghanistan foremost among them. Policy intellectuals in Moscow soon realized that this course was untenable, but as three gerontocratic Soviet General Secretaries died in as many years, they needed a leader who could actually reform Moscow's policy vis-a-vis its bench of Third World tyrants. That chance came with Mikhail Gorbachev, under whom Moscow begin to cut allies like Mariam Haile Mengistu (Ethiopia), Jose Eduardo dos Santos (Angola), and Najibullah (Afghanistan) loose.

If Gorbachev's Soviet Union soon came apart for reasons unrelated to its Third World adventures, the Soviet global moment had a massive impact on its Third World allies. After Boris Yeltsin cut Russian aid to Kabul, the Afghan Army and state collapsed. Angola managed to limp along with a series of shambolic ceasefires. While much of the country's population remains desperately poor, an oil and minerals boom has lent the country some of the highest GDP growth rates and levels of foreign investment in the world – good news for dos Santos, who remains in power. Less oil-soaked Mozambique, however, remains one of the poorest countries in the world. Ethiopia, which was an empire unto itself, was wracked by civil war and separatist movements as a direct result of the Communist regime's violence. If Cold War politics aided Eritrea's incorporation into an Ethiopian empire in the first place (in 1962), Moscow's improvised support for the Ethiopian Communist Derg created a conjuncture in which the primarily Tigrinya people of Eritrea could break out and form their own state again.

If you're wondering where the "Russia" or "China" is among all of this talk of Tigrinya and Pashtuns, that's precisely the point. Friedman's work reminds us how contingent the Soviet global mission was - how inextricably connected the Soviet project became with the concomitant processes of decolonization and the integration of China with the world economy. It seeks to show how "Russian history" and "Chinese history," particularly in the mid-20th century, were intertwined with events far beyond the borders of the Soviet Union or the People's Republic of China. At a time when many scholars are seeking to re-integrate the history of "the" Cold War with more catholic histories of the 20th century that treat the Cold War parallel to decolonization and other major shifts, Friedman's work promises to help re-orient the field. It demands that we tear down the walls and demolish the borders that arbitrarily separate "Russian history" from global history.

That's a message that "national" historians have responded to. Historians of "just" the Soviet Union or China have been supportive of the project, Friedman reports. And a recent voyage to Havana - to present before Cuban historians - resulted in a similarly warm welcome. One can only hope that Shadow Cold War makes his work visible to an even wider audience - one that extends beyond audiences interested in national history, or "Cold War history" per se.

But what of those phantom projects back in the dissertation prospectus? Shadow Cold War, Friedman explains, is really the first project embedded in his original research idea. While steering the book towards publication, he has begun research for an ambitious sequel - the second part of the dissertation prospectus - that evaluates the impact and legacy of the Sino-Soviet Split in five countries in the Third World: Indonesia, Tanzania, Chile, Angola, and Iran.

This quintet might not seem to possess much internal unity, but, as Friedman explains, together they have much to tell us about the global trajectory of the Left. Too often, he explains, we view the history of the Third World in terms of a "supply factor" - as a story of ideas pushed by Moscow, Beijing, and Washington. But there was also a demand factor, too. Countries had their own solutions in the struggle against inequality. Countries learned from one another. In tying together the history of countries which tried different Leftist solutions throughout the Cold War, we begin to perceive that global dialogue.

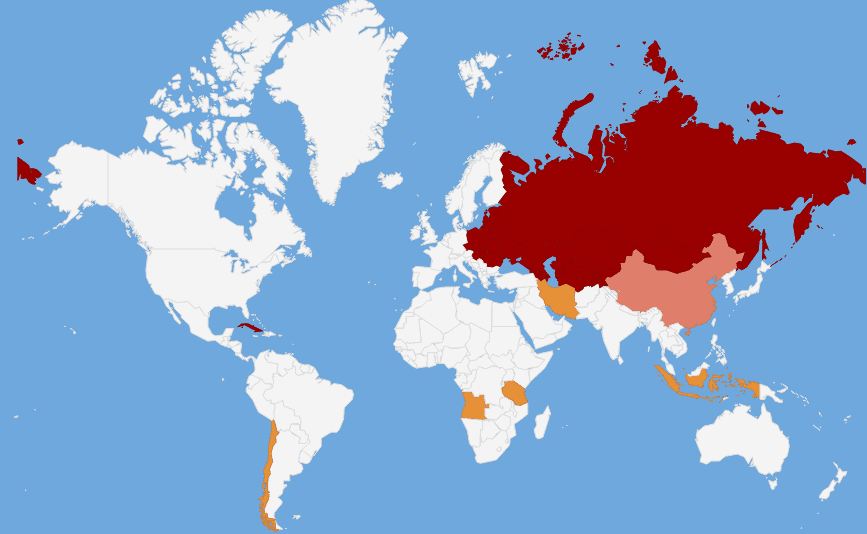

Sites of a "Shadow Cold War" - Indonesia, Chile, Tanzania, Angola, and Iran. Dark red indicates Soviet Union and client states; pink indicates People's Republic of China; orange the case studies for Friedman's second book project.

Indonesia forms the first case study. By the mid-1950s, the Southeast Asian post-colony had the largest non-ruling Communist Party in the world. The Partai Komunis Indonesia (PKI) generally cooperated with the post-independence Sukarno regime, which governed under an autocratic "guided democracy" after 1957. But as historians like UConn's Brad Simpson have shown, Indonesia was becoming a dangerous crucible for several ideological projects. American development economists and military planners fretted that Sukarno was becoming too dependent on Soviet military aid and was striding a path too close to socialism. Sukarno, wary of a right-wing coup from the military, appointed more PKI leaders into the government. The Soviet Union had initially supported the PKI, but in the wake of the Sino-Soviet Split, it began flirting with another Indonesian Communist Party, the Murba. In spite of Soviet pressure for the PKI to follow Moscow's example as the leading socialist power, the PCI itself looked to China for inspiration.

Even as the PKI had organized millions across the 26,000-island archipelago nation, it was caught between the global projects of the Soviet Union, Mao, and the Johnson Administration. After the mysterious killings of top Indonesian Army brass on the evening of September 30-October 1, 1965, the military launched a wave of gruesome mass killings against "Communists" across the country. The killings - justified in the name of protecting the nation from a PKI coup - claimed the lives of at least 500,000 people. The "counter-coup" paved the way for a wave of violence against all kinds of enemies, not just Communists. In Java, where support for the PKI was strongest, devout Muslims were recruited to butcher "atheist" Communists; in Bali, upper-caste Hindus were mobilized to slaughter the Balinese peasants who formed the rank and file of that island's PKI branch. Everywhere, premans ("free men," but more idiomatically, gangsters) conducted mass killings to enrich themselves, gain monopolies over smuggling or gambling, and to ingratiate themselves with the military. Sukarno formally remained in power and banned the PKI, but he was stripped of his title in 1967 and put under house arrest until his death in 1970.

The major alternative stalwart of Asian - and Muslim - Communism was crushed. China's role in the episode has long been murky. Allegations that Beijing armed the PKI and instigated its attempt to seize power have been around since the mass murders themselves, since this was the accusations that the Indonesian military used against the PKI. The destruction of the Communist Left in Indonesia may not have been hailed in Moscow, but the demise of the PKI at least provided Moscow with an example it could use to warn other Asian and African socialists. Communism began to seem "naturally" alien to Muslim countries, even though Indonesia had boasted the largest non-ruling Communist Party in the world. The Leftist struggle in Southeast Asia became defined by the Moscow-Beijing-Hanoi triangle and the fight against American militarism. Hopes for a richer dialogue between the PKI, Mao, and Ho vanished. Perhaps most consequentially, Indonesia itself became a laboratory for foreign investment and the authoritarian suppression of political Islam. Later, the military conducted a quarter-century violent occupation of East Timor - the only Portuguese post-colony that did not turn to the Left. It would be misplaced to engage in counterfactual nostalgia for a PKI-ruled Indonesia, but the long-term consequences of the Suharto regime both for Indonesians and the Left in Asia were dark indeed.

Tanzania forms the next chapter in Friedman's story. The British colony of Tanganyika became independent in 1961; the former teacher and political organizer Julius Nyerere became Prime Minister, and, later, President of the country. Swiftly consolidating a one-party state, Nyerere exerted control over foreign events when the offshore Sultanate of Zanzibar, long dominated by an Arab minority with links to Oman, had its own revolution in 1964. Zanzibar became part of a United Republic of Tanganyika and Zanzibar (soon renamed "Tanzania"); its Arab elite was subjected to brutal reprisals. Black Africans inherited the land and gained access to long-closed educational opportunities. The struggle against imperialism - white or Arab - was never-ending. Taking place at a time when people still viewed the 1960s as a "Decade of Africa" and white Portuguese & South African colonial or apartheid rule remained intact south of Tanzania, Nyerere's actions possessed great resonance.

Nyerere soon went further. In a 1967 Arusha Declaration he announced the principles for "African socialism": nationalization of all major enterprises, forced agricultural collectivization, cultivation of a national anti-tribal identity through patronage for the Swahili language, the criminalization of "non-African" goods and practices (miniskirts, Western media, and homosexuality), and admiration for the Chinese experience.

African socialism had a foreign policy, too. Nyerere supported guerilla armies opposing the Portuguese in Angola,helped overthrow Idi Amin in Uganda, and inspired revolutionaries to establish one-party dictatorships in the Seychelles and Vanuatu. Thanks to Nyerere's politicking, from 1970 to 1975 Chinese engineers built a massive railroad project connecting Zambian copper deposits with Dar es Salaam. While the Tanzanian economy was a mess by the time Nyerere left office in 1985, he had succeeded in creating a coherent and inspirational vision for an African Left. Rather than being condemned to permanent backwardness and tribalism, the post-colonial nation could retain "African" social organization through the villages while also coalescing around a national language. By 1986, the one-party state Nyerere had left behind - dominated by so-called Wabenzi ("people of the Mercedes-Benz") - turned to dismantle parts of the socialist project, but the ideological legacy remained great indeed.

As we move through Friedman's case studies, it might be worth pausing on a question that I asked during our interview: with all due respect to Tanzania and Angola, weren't more traditionally studied Cold War theaters like the Middle East or Central Europe for global history? Why not write about those cases? What specifically distinguishes Friedman's five countries from others along the USSR-PRC fault line - North Korea, per se, which was more closely allied with Moscow but could also not be ignored by Beijing?

Friedman clarifies. It's not particularly helpful, at least for historians interested in the intellectual history of the Cold War to think in terms of the "importance" of various theaters. China didn't have the resources - as it eventually conceded to the Soviet Union in the Third World - to compete with Washington or Moscow in more "expensive" conflicts. Tipping a conflict in Tanzania, Angola, or Chile was less resource-demanding than outgunning America in Israel, Pakistan, or Iran. China's limited economic and military resources hence had to be concentrated towards Third World theaters crucial to the Chinese national interest, namely Vietnam.

But conversely, it was in the more obscure corners of the planet where China could afford to be more ideologically intense, and where the intellectual stakes become clearest. China in the 1960s didn't have very many interests in Guinea, but precisely for that reason it could aggressively position itself against a Soviet Union suddenly tarred as "white," "imperialist," and "hegemonic." It's the interplay between posture - capable in less obviously significant areas - and geopolitics that most interests us here.

This also explains the countries or regions left out of Friedman's quintet. To take up the North Korea example again, the issue isn't so much that the USSR-DPRK-PRC triangle lacked significance as that figures like Kim il-Sung lacked a global profile. Leftist parvenus in Kabul, Managua, and Santiago weren't reading Kim, since he didn't offer an attractive solution to the problems of social inequality and post-colonialism that was obviously applicable outside of North Korea. For better or for worse, figures like Kwame Nkrumah, Fidel Castro, and Julius Nyerere did.

On to the next case: Chile. Events in Santiago provide geographical balance to Friedman's narrative, but their significance goes deeper than that. The victory of the Salvador Allende-led Popular Unity government in Chile's 1970 presidential elections appeared to provide a model of "peaceful transition" to Communist Parties around the world. Allende's success seemed especially relevant to other "Latin" countries with large, legal Communist Parties: first and foremost countries in Latin America, but also European countries like Italy and Spain. It bears remembering that by the early 1970s, the Italian Communist Party could still win more than a quarter of the electorate. As late as 1976 it racked up 34% of the vote. In Spain, meanwhile, the Communists got nearly 10% of the vote. Allende and allies offered a different vision of the Left's future than did Third World Communist Parties: win power through the ballot, not the bullet.

On paper, it sounded like a perfect turn of events for Moscow, which had invested heavily into the European Communist Left. And yet analysts in Moscow struggled to determine the allegiances of Allende's coalition government. Allende himself insisted that he was following "a second model of the transition to a socialist society" (the first model being the Soviet), and there were reasons to distrust the Chilean Socialists backing up his coalition government. The Socialists coexisted uneasily with the Moscow-backed Chilean Communist Party, remained neutral vis-à-vis China, and remained committed to armed revolution. Some Chilean Socialists sympathized with the Movimiento Izquierda Revolucionaria (Leftist Revolutionary Movement), a group whose members received military training in Cuba and whose revolutionary pamphlets (against peaceful coexistence and for armed struggle) sounded decidedly Maoist in tone. Worse, Allende's nephew was one of the group's leaders.

As Chilean foreign reserves collapsed, Kremlin élites questioned whether they really needed to support yet another client state (like Cuba) that challenged them ideologically and sucked away resources. And at near the peak of détente, challenging the United States on its home turf threatened Brezhnev's accomplishment of peace. The KGB provided logistical support to Santiago, and Moscow even approved the shipment of military supplies to the Allende regime, but Chile missed the boat – literally. When intelligence reports of an impending Army coup arrived in Moscow, the maritime shipments were redirected elsewhere. The risk that ultra-Leftist elements in the Socialist Party would grab the guns, forestall the coup, and turn Chile into a Maoist stronghold in Latin America were too great. As Friedman's dissertation explains, "In the context of the global Sino-Soviet conflict, the prospect of a Chilean revolution dominated by a Socialist Party which might lean towards Beijing was worse for the Soviets than a martyred revolution."

The failure of a "peaceful transition" through elections bespoke the Left's future. The major revolutionary victories the Left scored after Chile were through violent coups in Angola, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan, not through "peaceful transition" in Madrid and Rome. Détente would have to guard military victories in the periphery of the Third World, not a reversal of the postwar European settlement through the ballot box.

Indeed, as Friedman hopes to show, Angola, a Portuguese colony in southern Africa, would reveal much about the splits that had emerged in the Left. Part of Portugal's attempt at a "pluricontinental" nation-state, by the 1960s Angola seemed only to offer a softcore version of the racial state on offer in nearby South Africa. Reforms in the early 1960s granted blacks citizenship, but opportunities for blacks were so infrequent that many had emigrated to neighboring Belgian Congo, which seemed enlightened by comparison. Armed resistance began in the early 1960s, and the Soviets invested early into the MPLA, a Marxist-Leninist Party.

But the failure to overthrow Portuguese rule early heightened the stakes of the conflict. In the 1960s, Africa had seemed poised to become fully independent of white rule and economically vibrant. But by the mid-1970s, not only did many of the countries in the southern tip of the Continent remain dominated by whites (Rhodesia, South Africa, and occupied Namibia); worse, from the Soviet perspective, the Chinese had gained influence through the railroad and the perfidious Nyerere. An MPLA victory following Portuguese decolonization (1975) could not only boost Moscow's prestige in "black Africa," but would also throw a kink into Beijing's African ambitions.

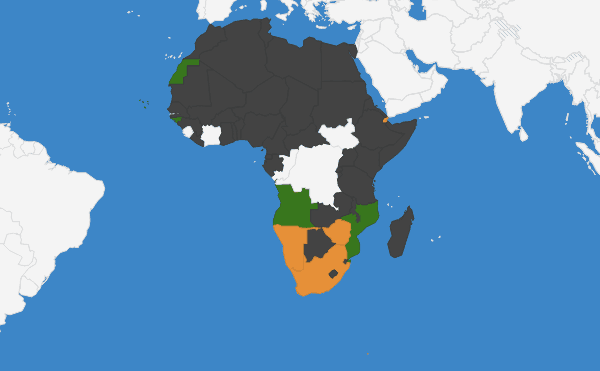

Africa, c. mid-1970s. Grey indicates majority rule; green European colonies; orange settler colonialist states and occupied territories.

Moscow - with the help of tens of thousands of Cuban soldiers - decisively kept the MPLA regime afloat for more than a decade against the South African - and American-supported UNITA opposition group. But as Friedman suggests, the Angolan epic was fundamentally significant because "it showed the difficulty in applying a revolutionary ideology based on class to a revolution whose protagonists saw their struggle largely in terms of race." By the mid-1970s, Beijing's opposition to the extension of Soviet power as the chief imperialist threat and to the mestizo elitism of the MPLA led it to supporting UNITA, an originally Maoist Angolan national liberation group. Crucially however, UNITA was also supported by Pretoria and Washington. In the eyes of many black Africans, the sight of the Chinese siding with South African racists was too much. Beijing had dealt a severe blow to its reputation.

Still, the Chinese's mere presence in the game had changed the terms of the Left's debate. Even as Soviet advisers poured into Angola to build a centralized authoritarian state and a disciplined Marxist-Leninist Party, challengers to the MPLA leadership persisted: why was one group of white colonizers replacing the other? Try as Moscow did to side itself with Leftist vanguards in Ethiopia and Afghanistan, it repeatedly found itself delegitimized as "white," "imperialist," and under attack from all sides. China sided with the USA in training and arming Afghan mujahideen, while in the Horn of Arica it literally moved into the Third World outposts where the Soviets had been kicked out, like Somalia.

The Iranian story, which Friedman is researching in more depth this summer, marks the end of the trajectory. For much of the early 20th century Iran seemed as likely as any of a country to have a socialist revolution. Iran actually had a decent number of workers, bordered the Soviet Union, and had been invaded or occupied multiple times from the north. Following the removal of Reza Shah and the joint Anglo-Soviet occupation of the country during World War II, the reconstituted communist Tudeh ("Masses") Party was one of the most significant forces in the country . That changed in the mid-1950s, when, after the 1953 anti-Mossadegh coup, the CIA and the Iranian secret services shattered the movement inside the country and forced most of Tudeh's leadership to base themselves in Eastern Bloc capitals. After a brief stint in East Berlin, Tudeh's Central Committee set up shop in nearby Leipzig.

When discontentment with the Shah led to his abdication and the beginning of the Iranian Revolution, the stage seemed set for a revolutionary turn towards the Left. Yet when revolution came to Iran, not only pro-democracy forces but also the Iranian Left were marginalized. Tudeh was allowed to participate in legislative elections, but under the leadership of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Islamic Republic annihilated the Party inside of the country once more. The struggle against Iranian monarchy had been successful, but the clerics had usurped victory from the Left. Still, Friedman hopes to recast the typical narratives about the "strange rebels" of 1978-1979 by placing them within the broader career of Revolution as a concept. Earlier, he says, it was the worker (represented by the Soviet Union) or the peasant (represented by Maoism) in whom the hopes of social revolution were invested. In Iran, however, Shi'a Islam was invested with the potency these former myths were. While the "Islamic Revolution" had its own endogenous causes, no doubt, Friedman seeks to show how it was also an outgrowth of the failure of workers', peasants' or African revolution.

For the moment, Friedman says, he's focused on getting the first book out the door and assembling the five case studies for the second project - that, of course, and attending to his duties at ISS and Yale. Still, he notes, the phantom third project lurking in his dissertation prospectus still excites him. Having mastered Chinese and Russian and explored the Sino-Soviet side of the Left's global history, Friedman entertains turning his attention more to the European and American New Left one day - its history on its own terms, as well as how the Soviet and Maoist Left reshaped the possibilities for the New Left. The linkages are there, Friedman explains, but "we artificially amputated the intellectual history of the Left" for obscure reasons. Opponents of the Vietnam War, feminists, and student protestors alike didn't want to be tarred as Soviet flunkies, and so they often de-emphasized the ways in which Moscow, Beijing, or their Third World points of light inspired their own projects for a European or Atlantic context. Hence, explains Friedman, "we don't talk about the history of the fight against inequality in a historic way."

It would be a welcome project. As the enthusiasm over French economist Thomas Piketty's recent Capital in the Twenty-First Century shows, concerns over income inequality, political economy, and the social question are fundamental today. Understanding the ideological journey that Euro-American discourse took away from anti-capitalism to anti-imperialism to anti-racism to its current ideological configuration is a crucial task for historians to lend clarity to current debates. That project might take some time to appear, but for now it sounds as though at least two projects to await from the polyglot and globe-traveler Friedman. Combining the best virtues of Cold War history with a global view, Friedman's work represents the bright future ahead for global history.