In the Shadow of Justice: An Interview with Katrina Forrester

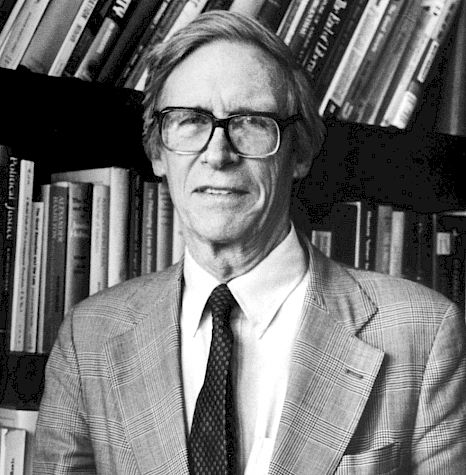

John Rawls was undoubtedly one of the most influential liberal political philosophers of the twentieth century. His most famous book, A Theory of Justice, was published in 1971. Prof Katrina Forrester, a historian of twentieth century political thought from Harvard University, tells the story of Rawls’s influence on liberal political philosophy in her recent book In the Shadow of Justice. Forrester shows how liberal egalitarianism—a set of ideas about justice, equality, obligation, and the state—became dominant, and traces its emergence from the political and ideological context of postwar Britain and the United States.

In our conversation with Katrina Forrester we discussed Rawls’s creation of A Theory of Justice, how he responded to critiques of his theory, and how his work continues to shape our understanding of war and society up to the present day.

— Julia Klimova

KLIMOVA: What inspired you to write the book? How did you become interested in Rawls?

FORRESTER: This book didn’t start off as a book about Rawls. In many ways, I still don’t conceive of it as being a book about Rawls; it’s a book that describes one part of the transformation of liberalism in the late twentieth century. I studied history as an undergraduate and was interested in writing about twentieth-century political ideas—I wrote my dissertation on Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, and anti-colonial thought in Vichy Martinique—and had also taken classes in the history of political thought. When I began my graduate studies, I wanted to write about the role of emotions and ideas of irrationality in twentieth-century social theory, particularly in critiques of liberalism. I got interested in Judith Shklar’s critique of liberal formalism and, because I was studying at Cambridge (where Cambridge School contextualism is the normal approach to studying the history of political thought) studying Shklar led me to her colleague and friend, Rawls. I had first encountered Rawls through Raymond Geuss, who reads Rawls as a vehicle for liberal ideology. When I eventually read Rawls himself, I saw that there was more to say about Rawls, even understood as an ideologist, and that it might be said by reading him historically. But I only came to that gradually. My doctoral work started off by looking at Rawls as one figure in a group of other postwar American liberals: it explored how they understood the nature of political theory and its relationship to politics, their ideas of utopia and realism, and the political valence and effects of their ideas. But it became clear to me that Rawls himself had transformed how political philosophers thought about political theory and politics—what questions they asked, how they answered them. These ideas about theory and practice were part of a larger historical story.

It’s worth saying that I am very much part of a generation of intellectual historians whose concerns and approaches were shaped as graduate students not just by the effects of the 2007-8 financial crisis and the turn to study neoliberalism, but also by the publication of Samuel Moyn’s The Last Utopia in 2010. There was this sense then that intellectual history could be political again, that it could intersect with the study of ideologies, the history of capitalism, legal history, international history, and that we could write genealogies of contemporary politics. At a personal level, I had been trying to work out how to bring together my political commitments with my academic work; Moyn’s book opened up a whole new set of questions. So I started to ask what would happen if we put analytical political philosophy – often seen as too abstract, or too technical to be political – back into histories of twentieth-century liberalism. What might that tell us, not just about political philosophy, but about how we periodize the ideological regimes of the twentieth century? In the Shadow of Justice was my attempt to think about those questions.

So I started to ask what would happen if we put analytical political philosophy – often seen as too abstract, or too technical to be political – back into histories of twentieth-century liberalism. What might that tell us, not just about political philosophy, but about how we periodize the ideological regimes of the twentieth century?

KLIMOVA: You start your book with an account of Rawls’s biography. How do you think his background influenced his work?

FORRESTER: Well, his background matters in a wide variety of ways. Rawls was both a vehicle for, and an innovator within, a certain kind of American liberalism. There has been an explosion in the study of the “historical Rawls,” with many scholars looking to put Rawls back into his various intellectual contexts. In The Shadow of Justice focused mainly on the political background to Rawls’s work—how the political dynamics of the postwar US and postwar American social and political thought shaped his preoccupations—rather than on his theological or philosophical context (though I spent a while trying to work through Rawls’s relationship to Wittgenstein). Rawls didn’t emerge out of nowhere, and despite the story that’s often taught by political philosophers, he didn’t revive political philosophy from its postwar slumbers. His political thought was part of a liberal response to changes in the twentieth-century administrative state—as Anne Kornhauser suggests, he’s one part of a longer legal tradition of critical liberalism—and also as a particular American response to the changes in global politics after World War Two.

To take a couple of examples: on the one hand, Rawls developed a vision of society that flattens certain types of conflict and prioritizes certain forms of consensus quite common among postwar “liberal consensus” theorists. On the other, Rawls also borrowed ideas from liberal critics of the administrative state—for instance, Frank Knight, one of the early neo-liberal economists at Chicago. These connections to mid-century liberalism were often submerged in Rawls’s published philosophical writings, so his unpublished materials collected by archivists at Harvard University are crucial to making sense of them. But it’s clear when reading those materials that Rawls’s account of society and the state emerged from a particular ideological constellation in the postwar US, when many liberals were skeptical about the extension of the state and were looking for novel ways to both legitimize and critique it.

KLIMOVA: Speaking of critique, in your book you write extensively about criticisms of Rawls’s theory. What criticism, in your opinion, would be the strongest and the hardest for Rawls to address?

FORRESTER: Rawls put a huge amount of effort into responding to philosophical objections. His responses, for example, to Thomas Nagel, H.L.A. Hart, or Richard Musgrave were all much studied. The archive has revealed many more debates to contemplate. Further, much of Rawls’s later work should be understood as extended replies to his philosophical critics—his account of international justice and his political liberalism. Some of the most famous critiques of Rawls—the communitarian critique, for instance—often rested on misreadings of his ideas, but Rawls responded to them anyway. Many political philosophers think that Rawls gradually made his own theory less viable and less coherent in order to account for all the objections, and I’m inclined to agree with them. But what I’m more interested in asking is what we should make of this broader conceptual landscape of objections and responses. Rawls, and philosophical liberals after him, became adept at responding to political and conceptual criticisms in their own terms. They defanged criticisms by translating them into their philosophical vocabulary. One of Rawls’s great strengths was the ability to squeeze all sorts of ideas into his theory, accommodating all criticisms. I’m interested in that capacity itself. It sometimes seems like political philosophers have become so good at dealing with objections that the practice of social critique has been rendered obsolete. But what does that tell us? Nancy Fraser has suggested we should think of the turn to normativity within both critical theory and Rawlsian liberal political philosophy not only as a mistake, but as a clue. What can we see if we treat Rawlsianism, distributive justice theory, as a symptom? Some political philosophers are quite willing to grant that description plausibility, but few really push on what it might mean. To me, that’s the most interesting kind of critique; and I think we’re better placed to answer it if we first make “Rawlsianism” into a historical object that can be analyzed.

KLIMOVA: Rawls’s theory focuses on North America and “the West”. Do you think it could apply to the rest of the world?

FORRESTER: Well, a whole generation of philosophers tried to argue that it could and should. In A Theory of Justice, Rawls’s own global imagination really only extended to a half-hearted engagement with modernization theory. The norm of a just society was very much based in a social-democratic society, which closely resembled the actually existing US in its broad contours. After that book was published, Rawls’s theory quickly set the terms of philosophical debate; but it also became a site of experimentation, as many innovated within the parameters that Rawls set. In the 1970s, there was an attempt by various liberal political philosophers, most influentially by Charles Beitz, to expand Rawls’s theory into a theory of “global justice,” and to stretch the distributive principles to apply to the global. So many political philosophers have, then and since, tried to show how Rawls’s principles of justice could apply to the rest of the world. It’s true that Rawls himself and much of the Rawlsian tradition of liberalism that followed him have focused on states that were much like the US. In fact, liberal egalitarianism—the theory that comes to dominance in Rawls’s wake—lacks the global ambitions of many other forms of liberalism.

KLIMOVA: It sounds like it was the role that Rawls’s followers took upon themselves to stretch his ideas more globally.

FORRESTER: Yes, that’s right. After Rawls, liberal philosophers used his theory as the starting point to make sense of their world. That was true of global justice theory, which began with liberal philosophers experimenting with Rawls’s principles of justice across space, and for intergenerational justice theory too, as they stretched his ideas across time. Rawls himself was insistent that his theory only applied at the level of the nation-state. He said little about the international realm, at least at first. In his early writings, Rawls mostly thought about international politics in terms of the duties and laws of war and peace. He gave his own account of just war theory during the Vietnam War, but he didn’t develop his international theory in more detail until the 1990s. By that point, there had been twenty years of debates about global justice. Those started off in the aftermath of the proposals for a New International Economic Order; the political origins of global justice theory are to be found in debates about decolonization and global redistribution at the end of empire. Yet, the engagement by liberal philosophers with political theories of decolonization was limited. In the 1980s and 1990s, they transitioned to debates about value and culture, international organizations, federalism, and multiculturalism—all of which put less pressure on their US-focused vision. It’s only really in the last decade that mainstream global justice theorists have returned to problems of colonialism and empire.

KLIMOVA: Rawls is writing during the Cold War. How do you think the bipolar system of the Cold War influenced his theory?

FORRESTER: Rawls didn’t really have an account of the bipolar system. Early on he drew from an anti-totalitarian liberalism that was common in the US in the late 1940s and 1950s. So, in that sense his early liberalism was structured by the Cold War—by an imaginary of totalitarianism. Yet he was worried more about the administrative state at home, as much as the totalitarian state abroad. As he developed his ideas, his mature theory wasn’t structured around an alternative: it wasn’t a theory of liberalism against communism. At the level of geopolitics, he wasn’t much of a Cold War liberal, but nor was he a critic of Cold War ideology. In his writings about the Vietnam War, there is little indication that he shared the New Left critique of the war. So, the mature Rawls isn’t really a “Cold War thinker,” except tacitly.

KLIMOVA: How do you think Rawls’s ideas on justice, morality, and equality apply to minorities, considering how unequal American society was at the time?

FORRESTER: At one level, Rawls’s liberal egalitarianism is perfectly able to give a robust defence of the rights of minorities. He was fully committed to equality of moral persons, and his principles of justice required limitations on inequality of a level that would make the kinds of racial inequality and injustice that characterizes US society completely impermissible. A number of Rawls’s interpreters, for instance Tommie Shelby, have argued that his theory is radical on questions of racial disadvantage. Now, in general, Rawls’s theory has been made to do all sorts of political work that Rawls himself may not have intended. But was Rawls himself concerned with the oppression of minorities? He was certainly a racial liberal. By that I mean that he cared deeply about racism and prejudice. From the outset he was concerned with constraining the effects of prejudice on social and political life and designing political institutions to do so. Further, as Brandon Terry has shown, during the civil rights movement, particularly after its major legislative successes, Rawls followed debates among African American thinkers more closely than many other white liberals. Yet, Rawls’s writings about civil disobedience are also an illuminating test case of the limits of racial liberalism. In the 1960s, when Rawls was preoccupied with the question of the justifiability of civil disobedience, he made clear that the civil disobedience of oppressed minorities was justified, but he constrained and limited their options in significant ways. So, despite finding racism and prejudice deeply objectionable at a moral level, and worrying about the political effects of racism—on individuals, on inequality, and on the possibility of political community—he did not exactly advocate heading to the barricades to revolt against Jim Crow. In keeping with the spirit of his broader theory, Rawls also understood racism more as an interpersonal or institutional phenomenon than a structural one. In his unpublished political writings on civil disobedience, Rawls came close to the liberal view that American society was nearly just except for the original sin and legacy of slavery. He didn’t interrogate the relationship of racism to the structure of American society or ask how minority status was itself produced by social and economic structures. So, while Rawls was certainly concerned with minorities, his theory wasn’t motivated by a political anti-racism.

I would say that the dominance of Rawlsianism itself contributes to the experience of the ‘end of history.’ That was true even if Rawls and other liberal egalitarians were individually disillusioned by that discourse and disappointed with where politics ended up.

KLIMOVA: Does Rawls have a response to Francis Fukuyama’s idea of the ‘end of history’?

FORRESTER: Not directly. Rawls’s liberalism was forged in part by the ‘end-of-ideology’ debates in the 1950s: he didn’t think ideology had ended, but he did think the US was in a period of ideological calm—a time when he could get on with philosophy and dig deeper into fundamental ethical questions. By the 1990s, when Fukuyama and others were debating whether the ‘end of history’ had arrived, Rawls was much less optimistic. In fact, he was pretty disappointed. There’s certainly an interesting story to be told about what happens to the ‘end of ideology’ generation at the so-called end of history. For someone like Rawls, a lot of his optimism was born of the postwar ideology of consensus. The civil rights movement also made him optimistic about the direction of American liberalism. By the 1990s, those hopes had come apart. Rawls became pessimistic about the future of capitalism and democracy. He did not greet the Third Way politics of the 1990s as a moment for optimism. There’s an irony here, since in that moment liberal egalitarianism does look an awful lot like a Third Way left-liberalism. In fact, I would say that the dominance of Rawlsianism itself contributes to the experience of the ‘end of history.’ That was true even if Rawls and other liberal egalitarians were individually disillusioned by that discourse and disappointed with where politics ended up.

KLIMOVA: As a liberal, does Rawls respond to feminist critique?

FORRESTER: Yes, he does, but only when he’s pushed and only with liberal feminists who directly engaged his work. As I’ve mentioned, Rawls had a tendency to try to accommodate objections to his work, and he was generous with his critics, but he often engaged with their arguments without really changing his mind or his basic commitments. I think that applies to feminist objections to his work too. Sophie Smith’s important forthcoming work on Rawls, Susan Moller Okin, and feminist philosophy, shows both how Rawls was receptive to liberal-feminist challenges, and how Rawlsianism silenced and marginalized its feminist critics.

KLIMOVA: Was he engaging with any other post-modernist critiques?

FORRESTER: The short answer is no, unless you include Habermas. Rawls didn’t engage with the theories often grouped under the category of postmodernism, if by that you mean, broadly speaking, the French and German thought described by Anglophone theorists as ‘continental theory.’ Habermas is the exception: Rawls debated with Habermas, but really only as Habermas became more Rawlsian. As he gave up some of his earlier commitments and became a social-democratic theorist of communication, he and Rawls had a lot to talk about. But more broadly, Rawls didn’t engage with poststructuralism, post-Marxism critical theory. That’s true not just of Rawls, but of much Anglo-American analytical philosophy. The second half of the twentieth century—the period when Rawls came to dominate political philosophy—was also the period when the so-called ‘continental-analytic divide’ was institutionalized in British and American universities. After Rawls, many liberal political philosophers redefined what counted as political philosophy in a way that excluded many of the alternative approaches to politics and society coming out of European traditions. These were often characterised as ‘social theory,’ rather than political philosophy. A new intellectual hierarchy was put in place, and many Anglophone philosophers justified not engaging with those traditions by appealing to it and describing these traditions as outside the bounds of what counts as political philosophy.

KLIMOVA: There is clearly a heated academic debate between Rawls and his critics; however, did Rawls’s theory make any impact on politicians at the time?

FORRESTER: Outside of academia, I’d say that Rawls has most influence on lawyers. There’s a history yet to be written about his impact on legal thought and practice. A generation of constitutional lawyers trained in Harvard, Yale, and NYU law schools in the 1960s and afterwards were influenced by Rawls and Rawlsian way of thinking. Some of Rawls’s ideas, and certainly liberal egalitarian modes of argument, came to have a subtle but important influence at the level of the law; they were transmitted through his colleagues and students, in debates about constitutional welfare rights and so on, and by liberal egalitarian legal philosophers who engaged with Rawls’s ideas, most famously Ronald Dworkin. There’s also a different history to be told about the influence of Rawlsianism on liberal policy-making, and the policy elites that gathered in the ethics centers and liberal think tanks founded in the 1970s.

But you’re right to imply that the history of Rawlsianism and liberal egalitarianism is in large part an academic story—about the elite institutions of academia in Britain, the US, and elsewhere, and their lack of influence on political life. That’s one of the puzzles that is revealed when you tell Rawls’s story historically. Why is it that such an influential theory within academia nonetheless had very little impact on the world outside it? There are a few ways to answer that question: one is to look at the theory itself and explain what it is about Rawlsianism, or liberal political philosophy in general, that made it quietist in this particular way. Another is to look at how liberals within academia failed to build liberal infrastructure outside the universities or failed to influence those who were trying to build that infrastructure. Both these ways are important to making sense of the successes and failures of left-liberalisms as public ideologies in the late twentieth century.

KLIMOVA: Do you think, if Rawls was working on his theory now, he would do something differently?

FORRESTER: I take all political theories to be entangled with the ideological context in which they originate, so yes, I do think that if Rawls were writing today, A Theory of Justice would be a very different book. Political philosophy has changed enormously since Rawls’s theory was published, and it was changed by his theory. So, it’s hard to imagine how political philosophy would have developed without Rawls. Perhaps another philosopher would have performed the same function, by synthesizing many different strands and approaches to analytical philosophy—debates about justification, decision theory, distributive justice—and bringing these together into a political framework characterized by the ideological commitments of postwar liberalism. Today such a synthetic project would be very different; we live in a very different material and ideological context. There were also particular institutional conditions in place in the postwar university that allowed for the publication of A Theory of Justice to become a major philosophical event—conditions that aren’t the same today. Not least is that Rawls took twenty years to publish his book, but circulated drafts in manuscripts that were hard to get hold of and much awaited. With today’s pressures, constraints, and technologies, it’s unlikely that could be repeated.

Crucially, the meaning of Rawls’s political ideas are also quite different compared to when he first put them forward. Liberal egalitarianism became a left-liberalism, but as the center-ground moved right, what it meant to be on the left changed. The late twentieth century saw a huge narrowing of ideological possibilities. So, Rawls’s arguments looked more radical, particularly some of their redistributive implications. With the recent resurgence of socialism, some have tried to recast Rawls as a kind of socialist. Historically speaking, Rawls wasn’t a socialist, even if some of his arguments might have socialist implications. To me, the move to make Rawls into a socialist originates in the same urge that drove philosophers to make Rawls into a theorist of global justice or racial injustice—the urge to find an authority, to invest a particular theory with all sorts of powers. Rawls’s theory is capacious enough that it can be all sorts of things to different people. I have my own political objections to it, but your question points us to other reasons to move beyond it even if those objections aren’t shared: that is, if there were a philosopher called Rawls writing today for the first time, his work would be different. So, ours should be too.

To me, the move to make Rawls into a socialist originates in the same urge that drove philosophers to make Rawls into a theorist of global justice or racial injustice—the urge to find an authority, to invest a particular theory with all sorts of powers.

KLIMOVA: Do you think his work on morality and war affected our understanding of international conflict in any way?

FORRESTER: The circle of philosophers that formed around Rawls during the Vietnam War, which included Ronald Dworkin, Thomas Nagel, Thomas Scanlon, Michael Walzer, among many others, had a huge impact on the way philosophers thought about war. Rawls and Walzer revived just war theory. Rawls was lecturing on just war theory in the late 1960s, and Walzer published his famous Just and Unjust Wars ten years later, which went on to be very influential. Many of them were also crucial to the development of the study of ethics in war—from the revival of the doctrine of double effect and the distinction between killing and letting die, to ideas of the moral responsibility of leaders and dirty hands problems. Significantly most of these ideas were not concerned with the politics of war or its institutions. In that sense, they were apiece with the broader humanitarianization of war that occurred with the rise of the human rights paradigm. I wouldn’t say those larger changes are caused by Rawls (and in fact Rawls stands out from his contemporaries in the late 1960s as being willing to think about many of the political aspects of the Vietnam War, such as conscription). But the transformation of political philosophy that Rawls and his contemporaries oversaw was certainly part of—and contributed to—a broader shift in our understanding of international law and conflict.

KLIMOVA: One last question about the book. Could you tell us about the cover?

FORRESTER: The book is about what happens when people get trapped in structures of their own collective making, despite what they might have intended or desired as individuals. I wanted an image to convey that. A friend suggested the work of the eery mid-century US artist Joseph Cornell. His famous shadow boxes portray magical worlds made out of quotidian found objects. From his basement on a New York City street (the aptly named Utopia Parkway in Queen's), Cornell built boxed-in dreamscapes that were sanitised, peaceful and safe. The image on my cover, Planet Set, Tête Etoilée, Giuditta Pasta (dédicace) (1950) includes celestial maps and planets, and a distributive theme: the planets are distributed between the glasses, one of which is smashed. Like many of the shadow boxes, it pictures a dreamlike utopia that looks perfect but isn’t. Things aren’t quite as they should be, and the worlds inside the frame are contained, but only barely separated from the messiness outside. It’s an image that captures something of the story of liberal political philosophy—its creation of ideal societies and conceptual languages that strive for internal coherence but have an ambiguous relationship to a political and economic reality they can never fully escape.

KLIMOVA: Thank you so much for such an insightful conversation about Rawls. In conclusion, can you tell our readers a little bit about what you are currently working on?

FORRESTER: My new project looks at feminist theories of work, mostly in Britain and the US in the long 1970s. I spent more than a decade writing about liberalism; now I’m going back to its critics. I’m particularly interested in how socialist feminists transformed modern understandings of work and class, and how debates about domestic labor, patriarchy at work, and sex and the state gave us a range of ideas, from emotional labor to sexual harassment to social reproduction theory. As we try to confront the future of work and crisis of care today, the successes and limits of these feminist efforts to grapple with work amid the consequences of deindustrialization and transformation of postwar welfare regimes are a good place to start.