Liberalism in Pre-revolutionary Russia: An interview with Susanna Rabow-Edling

The Russian Empire has often been associated with autocracy, illiberalism and backwardness. However, Russian liberal intellectuals worked to modernise and liberalise their country, while preserving its international influence and position as a world power. In Liberalism in Pre-revolutionary Russia: State, Nation, Empire (Routledge, 2018), Susanna Rabow-Edling looks at the history of liberal nationalism in the Russian Empire, covering the period between the Decembrist revolt in 1825 and the October Revolution in 1917. She examines liberal tendencies in the Empire and how they are intertwined with notions of nation and empire.

Susanna Rabow-Edling is Associate Professor in Political Science and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Uppsala University in Sweden. In our conversation, we discussed the development of different Russian liberal theories, the role of nationalism in a multi-ethnic empire, and the parallels between Russian and Western liberal ideologies.

— Julia Klimova

JULIA KLIMOVA: What inspired you to write this book?

SUSANNA RABOW-EDLING: Actually, I started thinking about this book project a long time ago. In nationalism studies, where I started out, it was taken for granted that liberal nationalism was a Western phenomenon that did not exist in Russia. But when I studied Russian cultural nationalism for my first book about Slavophile thought (Slavophile Thought and the Politics of Cultural Nationalism, SUNY Press, 2006), I realized that this was simply not true. I also came to realise that research about Russian nationalism and research about Russian liberalism were pursued separately from each other. At the time when people emphasized Russia’s conservative tradition, I thought it was important to draw attention to the tradition of liberal thought in Russia and the way it was linked to both nationalism and imperialism. I wanted to question the contrast between East and West, according to which Russian nationalism is conservative and ethnic, whereas Western nationalism is seen as civil and liberal, hence good. I found that this view of Western nationalism has been questioned a lot while the view on Russian nationalism had not been questioned as much. This contributes to an essentialist view of Russian culture as fundamentally different from Western culture.

I wanted to question the contrast between East and West, according to which Russian nationalism is conservative and ethnic, whereas Western nationalism is seen as civil and liberal, hence good. I found that this view of Western nationalism has been questioned a lot while the view on Russian nationalism had not been questioned as much. This contributes to an essentialist view of Russian culture as fundamentally different from Western culture.

KLIMOVA: It is really interesting to see this coming from a nationalist studies perspective. Did you find that there was a separate concept of “Russian liberalism” as opposed to “Western liberalism” or not?

RABOW-EDLING: My book is really about liberal nationalism in Russia, not about Russian liberalism, but I can say that some students of Russian liberalism have argued that this is a distinctive form of liberalism. They commonly emphasize its conservative and statist character in order to contrast it to classical Western liberalism, which they claim is focused on individual rights and a limited state. However, I believe that this is a simplification. In my view, liberalism is a very broad concept that covers a lot of very different ideas. So, I believe that there are many forms of liberalism in both Western history and Russian history and they vary in time and space. Different versions of liberalism also existed at the same time, but you cannot really say that there is one Russian liberalism and one Western liberalism. Instead, we need to study these ideas in their historical context to understand their meaning.

KLIMOVA: How did you decide which groups of liberals to include and which to omit?

RABOW-EDLING: I made this decision based on the centrality of certain groups to the history of Russian thought. I chose to investigate four intellectual movements in the history of Russian liberalism (Decembrists, Westernizers, Early Russian liberals, and Kadets (Constitutional-Democrats)) when liberal nationalism was particularly pronounced.

KLIMOVA: Following up on that, part of your book touches upon Westernizers (or Zapadniki)—how do they fit into “Russian liberalism” and “Russian nationalism” considering their pro-western position?

RABOW-EDLING: When I use the concept of “Russian liberalism” I mean liberalism in Russia. Even though some liberal ideas tend to be more predominant in Russian liberalism, I am not arguing that this liberalism is essentially different from liberalism in the West. So, there was no contradiction in the 1840s between being a Russian liberal and taking a pro-Western stand. Neither was there a contradiction between being a Russian liberal and a Russian nationalist. Regarding the Westernizers, one needs to qualify their pro-Western position. What did this position mean and what did they really want to achieve? They wanted Russia to take the Western path of development, but they were clearly against imitating the West. According to the Westernizers, Russia could modernize on the basis of Western ideas without losing its national distinctiveness. They wanted Russia to borrow from the West only what was needed and to transform it into something original and Russian. That way Russia would be able to develop organically from within, but on a foundation of Western learning.

I also talk about this in my first book about the Slavophiles: about how the Westernizers’ ideas were formulated as a solution to a common problem that the Slavophiles also experienced. It is the common problem of the feeling of backwardness in relation to the West. Imitating the West would not solve this problem—they really wanted Russia to produce its own culture, but it should be done through Western modernization.

KLIMOVA: There were of course many debates on how to modernize Russia, and one was between Gogol and Belinsky. You mention Belinsky and his rather radical approach to Russia’s future. Could you elaborate a little bit on the debate between Belinsky and more conservative Gogol considering that both of them wanted to liberalize Russia but had a different approach?

RABOW-EDLING: Belinsky had great hopes for Gogol: that he would represent the new Russian culture, which he subsequently did. However, Belinsky became very disappointed in the way he believed Gogol had changed. What Belinsky found interesting about Gogol was the way that he described the “real” Russia and thus contributed to expressing Russia’s national identity, but he became disappointed when Gogol embraced mysticism and developed religious inclinations.

KLIMOVA: Gogol definitely took a very pro-religious position in their debate, which brings us to the next question: to what extent was church and Orthodoxy important in the debate on Russian liberal nationalism?

KLIMOVA: Gogol definitely took a very pro-religious position in their debate, which brings us to the next question: to what extent was church and Orthodoxy important in the debate on Russian liberal nationalism?

RABOW-EDLING: I have not really focused on religious thought in this book. My background is in political science, so it is more natural for me to focus on political ideas. Moreover, I think that other people have already done excellent work on religious thought. Regarding the Decembrists, there is not much in the political documents or the civic literature about religion, other than the need for freedom of religion as a basic liberty. Although they did see Christianity as a norm, other beliefs were accepted as long as they were not contrary to what they called “the spirit of humanity.” Orthodoxy was important to some of the Decembrists both on a personal and political level, but there were also Catholics, Lutherans and Atheists among them.

KLIMOVA: Of course, the concept of nationalism brings us to the idea of national minorities, who were numerous in Russian Empire. How did these liberal groups perceive non-Russian national minorities and what was their place in nation-building before 1905?

RABOW-EDLING: This was certainly something that they talked about. I would say that in general they took a paternalistic or imperialist view of non-Russian national groups. Again, there was nothing new about this and this position. It was completely in line with liberal nationalists in the West, who often used nationalism to justify imperialism. Some Decembrists promoted federation, and others promoted a unitary state, but all of them presupposed some degree of cultural assimilation among Russian peoples. The idea of granting special rights to ethnic minorities is a very modern concept. Liberals at the time, both in the East and the West, called for equal rights to benefit the common good. They struggled against autocracy and aristocratic privileges. There was really no place for minority rights on this agenda.

At the time of the Kadets (Constitutional Democrats), the nationalities issue had become much more important. There were different views on the nationalities question inside the Kadet party, but the general line was that the forced russification must cease, Finland and Poland should be allowed greater autonomy, and non-Russian nationalities should be respected, given full civil rights and equality before the law, as well as the right to cultural self-determination. Lastly, Russia’s national integrity should be preserved, and the Russian language should be the language of the central institutions, the army and the navy. The Kadets in a sense promoted a combination of state unity and cultural diversity. They wanted to treat minorities fairly, while maintaining a strong Russian state. Pavel Miliukov, the head of the Constitutional-Democratic party, continued to promote the idea of cultural autonomy that the Kadets had presented in their program. However, there were disagreements and the interesting character here is Petr Struve, who agreed with Miliukov and the main party line with regard to Finland and Poland, but he differed from them regarding other nationalities, especially Ukraine. Struve was prepared to grant extensive internal autonomy to Finland and Poland, but he found it difficult to accept even the existence of a separate Ukrainian culture. I think this is because he saw Ukrainians and Belarussians as part of the Russian national core, so he could not allow for these cultures to exist separately. Following a long line of Russian and Western colonial thinkers, he argued that the stage of cultural development determined the people’s relationship to the Russian core. The ties between different parts of empire could be political, as in the case of Poland and Finland, which had cultures of their own, or both political and cultural, as in the case of what he saw as the less developed periphery, which needed Russian culture in order to develop. These ideas were not as prominent in Miliukov’s writings, but he did consider it appropriate that the nomadic peoples in Russia should be pushed to a “higher cultural level.”

I think Struve is really interesting here. He belonged to a small group of political thinkers who promoted the idea of multi-ethnic Russian nation, which ideally would cover the whole empire. This meant a gradual expansion of the all-Russian national core in order to fill the boundaries of the entire imperial state, but this expansion would be accompanied by political participation and civil rights. He justified the policy of expansion by claiming that it would be based on the rule of law and a representative political system. He saw Russia as a nation in the making, which is a very interesting concept. He argued that Russia, like the United States, had assimilated a number of different cultures and that Russia was not yet a fully formed nation, but that it was being forged into a single nation by the process of cultural integration. In this process of cultural integration Russian culture played the same role as English culture in America. On the other hand, Struve did not believe that assimilation was feasible in Finland and Poland, because they had national cultures of their own, but that it was viable in the rest of the empire. He believed that in this Russian nation there would be greater scope for preserving minorities’ cultural distinctiveness than in the United States of America.

KLIMOVA: Do you know if Struve’s position changed in any way later on?

RABOW-EDLING: Well, when the First World War broke out, it made many people more patriotic. This included Struve as well, making him more conservative and supportive of the government. However, the World War reinforced nationalist tendencies among the Kadets in general, so, when the war broke out, the Kadets urged their party members to support the regime to preserve the unity and integrity of their county, and to defend its position as a world power. This meant that they all took a more conservative stand. For instance, they argued that universal suffrage would divide the country and harm the war effort. Instead, they were willing to cooperate with the government. However, it is important to emphasise that nationalism was always one of the party’s most fundamental values. This is reflected in their commitment to the welfare of the whole of Russia, rather than to a particular social class. It is also reflected in their belief in the significance of the state.

The first concept of commitment to the welfare of the whole of Russia is really interesting, because the idea of the intellectual as a servant of the nation came from the time of the formation of the educated elite in Russia, and it was a part of the self-identity of Russian intellectuals. The concept of a strong state was fundamental to the ideology of both liberal Westernizers and early Russian liberals, but not to the Decembrists. The fact that many Russian liberals from the 1840s onwards believed in the importance of the state as an actor in liberal reform is often taken as a sign of the persistence of Russian autocracy, but the state played an important role in European liberalism as well, particularly in the late 19th century, but also in the post-Napoleonic era. Even classical liberals realised that the state played an important role. One can say that these liberals fought against the state. Well, in a way they did, but they did not fight against the state per se, they fought against a certain kind of state: an autocratic, unlimited state founded on privilege. So, we have to realize that we do not really know what they would have thought about the kind of state that appeared in the later period. Many European liberals, contemporary to the Kadets, argued in favour of social liberalism, promoting social reform and a strong welfare state. Social reforms were essential to the Kadets if they wanted to secure a broader support base among the people, who were mobilized by the socialists. On this matter they were actually influenced by the social reformism of the new liberalism in England and France.

KLIMOVA: A similar support for the state occurred with the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war in 1904. However, liberals quickly changed their position against the regime. What do you think triggered this radicalization of liberal opposition?

KLIMOVA: A similar support for the state occurred with the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war in 1904. However, liberals quickly changed their position against the regime. What do you think triggered this radicalization of liberal opposition?

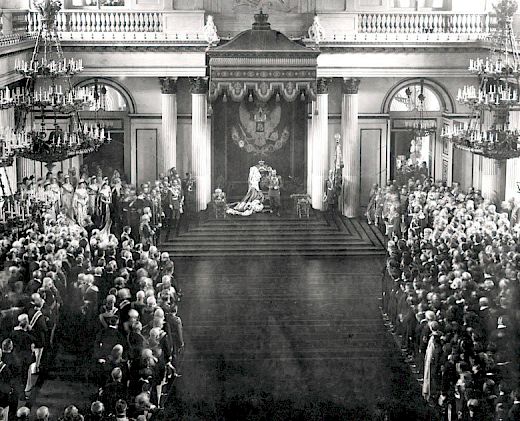

RABOW-EDLING: Many were disillusioned with the conservative policies of the regime after the assassination of Alexander II. They were especially displeased with the weakening of the zemstvos, since these organs of self-governance had really been the stronghold of liberalism. Liberal constitutionalists both within and outside of the zemstvos started to create a national liberation movement with a rather broad democratic program. Already in 1904, the coalition between democratic intelligentsia, zemstvo liberals, and liberal academics formed the Union of Liberation, demanding constitutional rule, freedom of assembly, and civic liberties. They had already stated to alienate themselves from the regime, of course, the events of the Bloody Sunday and the shooting at the workers’ peaceful march to the winter palace to deliver a petition was vital in people turning against the tsar. Finally, the defeat in the Russo-Japanese war added to the loss of loyalty. This was an ongoing process already before the start of the war with Japan.

KLIMOVA: We talked a lot already about inevitable parallels between Russia and the West. How does liberal imperialism in Russia generally compare with Western Empires? In your book you mention the comparison of Russian and British Empires and the parallel with Poland and Ireland, however, Russian Kadets often compared other borderline areas with less developed British colonies, rather than with Ireland.

RABOW-EDLING: This has not really been the focus of my research, but it would certainly be interesting to look into this more. An important note on terminology: I am using the term “liberal imperialism” to denote a set of liberal ideas concerning empire, not to refer to the faction of the British liberal party calling themselves liberal imperialists, who tried to construct a liberal argument in favour of Empire. I wanted to see if there were any similarities between the Russian case and Western countries, precisely because other scholars have been focusing on differences. My interest lies in the ways that liberalism, nationalism, and imperialism were interconnected and the fact that Russian liberals’ notions of empire are not so different from Western ones. Of course, there are differences since ideas have to be adapted to the context in which they are developed in order to be meaningful. If we take Britain, Germany, and Russia, for instance, they were very different empires and the role of liberalism in these empires was also different. The point is that there were various forms of liberalism and various forms of imperialism and that these were connected in different ways. However, both in Russia and in other empires the liberal model of imperialism was used to justify despotic rule over other people. They did this either by linking imperial rule to a project of improvement, enlightenment, and civilization, or by linking it with economic modernization and the survival of the state. Liberal imperialism was also playing a role in the territorial expansion of other Western countries, which were not seen as empires, for instance, the United States of America. This subject is something that I would like to investigate further.

KLIMOVA: Summing up your book, how did liberal nationalism in Russia evolve since Decembrists to the Kadets?

RABOW-EDLING: To start with the Decembrists, I think that this group was bolder and more radical both in terms of ideas and activities. They were influenced by western thinkers and political events and considered it natural to borrow western ideas and models in order to modernize Russia. They never really doubted that Russia could and should follow the western path, or that western models could be applied in the Russian context. This position is quite different from the later period. After the failure of the Decembrist revolt, liberal ideas became more ambiguous, cautious, and moderate. Liberal nationalism became a solution to an identity crisis among the educated elite. The Westernizers expressed liberal ideas in a rather abstract and metaphysical way. They also had to deal with the problem of imitation from the West and Russia having to create its own national culture. After the death of Nicholas I in 1855, liberals made more explicitly political statements, as it became possible at that point. Liberal ideas were also given a more instrumental function. Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War in 1856 made it evident that Russia was on the brink of disaster. Liberalism was seen as a way to save Russia and to re-establish Russia’s power and influence as a great power in Europe. They really believed that if liberal reforms were not introduced, Russia would stagnate politically, economically, and culturally. During the second half of the 19th century, empire and imperialism became central to liberal thinking and, like in the West, Russian liberals both criticised and justified imperialism. Struve, for example, was against what he called the forced imperialism of the regime, but he argued that a liberal nation at home had to be combined with external power. In order to survive in the modern world, states had to be imperialist. In that period, nationalism, liberalism, and imperialism were seen as necessary for Russia to modernise. The problem was that liberals could no longer ignore the demands for minority rights, and this created a tension between the need for liberal reforms and the effort to preserve the integrity of the empire. Eventually liberal nationalism which was once rather radical, turned into a conservative ideology and the nation that the Kadets proposed in 1917 was far too exclusive. It came too late and was too restricted. It was not only the lower classes who felt excluded from the Russian nation, but also the ethnic minorities.

KLIMOVA: Thank you very much for this fascinating interview. In conclusion, could you tell us a little bit about your current research topic?

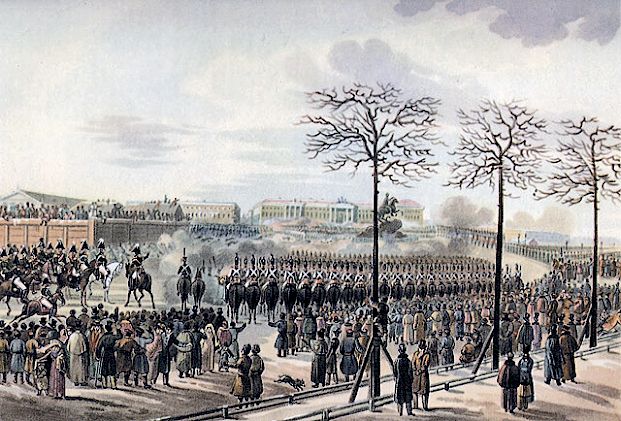

RABOW-EDLING: I am trying something that for me is completely new, namely writing a book for the general audience. I was approached by a publisher about writing on the Decembrist uprising and thought I would give it a try. Because so many people think of Russia as different, I think this is an interesting example of a historical event where there are many parallels with the West. My book will explore the unfolding of the dramatic events of the uprising of 14 December 1825, when Russian officers lead 3,000 soldiers to the Senate Square in the centre of St. Petersburg to force the senate to approve their constitution. I am interested in exploring the reasons that made the Decembrists risk their careers, their privileges, and even their lives. What did they wish to achieve, what kind of society did they imagine, and why did they fail? What were the consequences of the uprising for themselves, their families, as well as the Russian society in general?