City of Light, City of Revolution: Walking the Streets of Anti-Imperial Paris with Michael Goebel

Paris, nous t'aimons! For centuries, foreigners have come to Paris with the expectation of reinventing themselves, finding inspiration on the Left Bank, or simply being bowled over by what was–once if not now–the European cultural capital par excellence. For decades after American writer Ernest Hemingway spent a much-mythologized few years in the French capital, wannabe writers would frequently waste a few years moving from café to café along the Seine in hopes of making their prose more like that of Hemingway's, or indeed other writers from the Lost Generation. Today, as a burgeoning East Asian middle class seeks to explore the City of Lights, the institution of the stay in Paris has taken on new dimensions, as Japanese and Chinese tourists reportedly suffer from "Paris Syndrome," whereby an exaggerated, romanticized view of the French metropole quickly gives way to the reality of cigarette butts, push Parisiens on the Metro, and–in lieu of Maxim's–the encroachment of le Big Mac onto the French diet, if not also waistline.

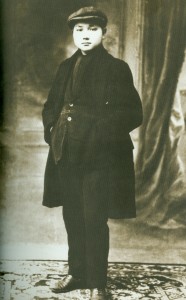

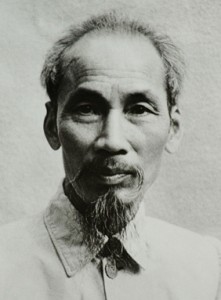

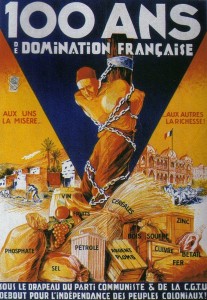

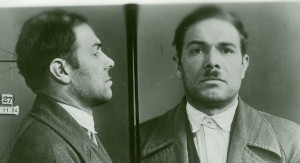

Paris, in short, defiantly challenges the stereotypes that both travelers East and West so readily project upon it. But as the work of Michael Goebel, Professor of Global and Latin American History at the Freie Universität Berlin and the latest guest to the Global History Forum, shows, scraping off the romantic stereotypes attached like barnacles to the banks of the Seine might make not only for a more realistic engagement with what remains a great city, but also with the history of the emergence of the "Third World." For as Goebel shows in his new book, Anti-Imperial Metropolis: Interwar Paris and the Seeds of Third World Nationalism, Paris has long played host to a rather different cast of characters than the romantic writers of the 1920s, or the stick-figure models imagined to inhabit the city by so many Asian tourists. More compellingly, during the 1920s and 1930s, Paris played host to an astounding array of intellectuals who would go on to lead national liberation and Communist movements around the Global South in the decades to come. Some of them, like Ho Chi Minh, Zhou Enlai, and Deng Xiaoping, are familiar to almost everyone; others, like George Padmore, César Vallejo, and Messali Hadj, perhaps less so, even if they, too, played a fundamental role in the making of African, Peruvian, and Algerian history. During the interwar years, Goebel shows in his tightly argued book, published by the Global and International History Series of Cambridge University Press this fall, Paris became a crucial incubator for different models of anti-colonial confrontation that would reshape the world in decades to come.

Recently, Goebel made a visit to Harvard University to present his work at the Harvard International and Global History Seminar. Before the talk, Toynbee Prize Foundation Executive Director (and fellow author in the International and Global History Series that Anti-Imperial Metropolis appears in) Timothy Nunan sat down with him to discuss the making of the book and his future plans as he seeks to integrate not only the history of metropole and colony, but also–as we find out in the conversation–of social and intellectual history.

•

As we find shelter from the rainstorms pounding New England on the day of Goebel's seminar, we ask him about the road to writing Anti-Imperial Metropolis. His answer–through Latin American history–might surprise some, but not those who are aware of the French political capital's longstanding role as a de facto intellectual capital of Latin America. Having graduated high school in West Germany, Goebel explains, he had the choice of whether to perform military service or civil service, either in Germany or a country of his choice. He chose the latter, and spent some time in Argentina, perfecting his Spanish but also exploring the possibilities for a profession that could take him out into the world and to write about it (his family, he explains, were physicians, and while he read history as a youth, there was no strong expectation that he would go into the field). Goebel came back to Germany after his civil service in Argentina to study history, but he soon grew bored with the dominant national focus of the way that discipline was taught in Germany. After a brief but abortive stint in journalism, moreover, it was not clear what to do next.

He applied for doctoral scholarships, and London came calling, in the form of a PhD bursary at University College London. The pressure there "for Germans to do German history, and Italians to do Italian history" was strong, and Goebel initially thought of working in the field of Holocaust history. But he resisted, and eventually turned his focus to Latin American history, which he had some exposure to thanks to the time in Argentina. He put his head down, headed to the archives, took up teaching positions and a post-doc in the UK, and by 2011, he was the author of a book, Argentina's Partisan Past: Nationalism and the Politics of History (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2011).

With the first book heading to the presses (and later translated into Spanish as La Argentina partida: nacionalismos y políticas de la historia), Goebel began thinking of what to undertake for the second project. His exposure to a Latin American world of ideas had him inspired to bring the French connection into his work, and so he embarked unto the French archives in Paris and in Aix-en-Provence (the latter home to the archives of the Outre-Mer). In an important lesson for those embarking on dissertation or book research, however, Goebel did not initially find what he was looking for. The French police reports he read between Paris and Provence did feature Latin Americans, but not in a role that had the makings of a blockbuster second book. Stories of drunkenness, sexual peccadilloes, and petty crime abounded; anti-colonial collaboration (mostly) did not.

But the more that Goebel persisted in the archives, the more he found another world of characters appearing in them: some of them denizens of the French Empire itself, like the Vietnamese ("Indochinese") and Antilleans; and others, from possessions like Algeria, not formal colonies and not overseas departments; and others still, foreigners to the French Empire altogether, like Chinese. The police struggled to keep track of them, and while there was plenty of petty crime, as with the Latin Americans, Goebel was intrigued that much of the material he found had to do with mutual aid societies, sporting clubs, and institutions designed less for political agitation than for easing the arrival of fellow countrymen to a city then as now not always famed for its hospitality.

Why were these people in France at all? The more Goebel dug, the more he found answers to these questions. During the First World War, he stresses, more than 750,000 denizens of the Empire, plus many recruited Chinese, either served in the French Army or worked in metropolitan France. While most returned "home," many stayed in the metropole after their service, politicized and more ready to make demands of the French state than before. During the 1920s, a recovering French economy depleted of (white) French bodies who perished in the First World War sucked in labor from around the world, especially from Indochina and Algeria but also from China, too. By 1930, just as the Great Depression was rocking Atlantic economies, there were some 100,000 "non-Europeans" and 400,000 "foreigners" in Paris and its environs, about half of whom were North African Muslims, like the aforementioned Messali.

The familiar contours – new friendships but plenty of exploitation – of labor migration took shape. Not only did many subaltern arrivals share apartments with one another, sometimes they even participated in "bed-sharing" arrangements whereby two or three men would share the same single bed in twelve- or eight-hour shifts when not working shifts at a nearby factory. The situation was far from the banlieues of late 20th century France, but a large black and brown proletariat had moved in to stay.

Readers of the piece, or indeed Anti-Imperial Metropolis itself, might wonder at this point: isn't the book "really" about ideas? What is the point of going into such detail on labor and living arrangements if the real story here is the emergence of nationalism among intellectuals? Not only is Goebel aware of this critique, his response to it forms perhaps the main argument and methodological advancement of Anti-Imperial Metropolis – namely, that social history and global intellectual history are mutually constitutive of one another, or that they are even the same thing. As Goebel writes in the introduction to the book,

in order to truly understand how [intellectual] transfers worked, we need to attend to the social bedrock of ideas. That is, we must grant more attention to the everyday experiences of non-Europeans in the metropole. In contrast to the existing historiography on the subject matter, this book is therefore much more of a social history of migration than an intellectual history of anti-imperialism. The latter, in my view, is more firmly rooted in the former than is commonly acknowledged.

We ask Goebel what he means by this more concretely. During the 1920s and 1930s, he explains, many of the migrant populations that moved to Paris faced a bevy of practical tasks–how do you get into a bed-share, much less a job, without knowing French?–that were more and more handled by mutual aid societies that were run along national lines. Sometimes, they found people jobs. Other times, they agitated for pension benefits to imperial subjects who had fought during the Great War. Other times still, more morbidly, they secured those who had died in Paris space in national or religious sections of cemeteries. The list goes on: child care, cheap credit, legal advice, health care, access to the Paris Mosque. Many figures like Lamine Senghor (no relation to Leopold Senghor) or Ho Chi Minh joined such fraternal aid organizations en route to joining more political organizations. The contradictions inherent in a European liberal tradition that also maintained the inequalities of empire were apparent to almost everyone who went through the migrant experience, but perhaps even more so for those migrants, like Messali or Nguyen The Truyen (Ho Chi Minh's Parisian placeholder after Ho went to Moscow) who married French women and became more aware of the racial prejudices of French society.

Understanding these social roots of anti-colonial nationalism is important more broadly, explains Goebel for how it stands to enrich our understanding of what such movements were actually about. There can, he notes cautiously, sometimes be a danger in global intellectual approaches that seek quickly–sometimes too quickly–to locate anti-colonial traditions within an ascetic philosophical debate about human freedom. Such work that might locate South Asian peasants as exponents of European liberalism, or Haitian rebels as the unfolding of the Hegelian world-spirit, certainly has its place in de-centering Europe from traditional narratives of global intellectual history.

But, notes Goebel, it also runs the risk of removing the rights and responsibilities of citizenship from the central place they held on nationalists' menus of change. Placing his work in the same context as Frederick Cooper's recent work on citizenship and empire, he underscores that for many whom we would see, in retrospect, as anti-colonial nationalists, the first aim was not always immediate national sovereignty (it was for the Vietnamese, but not necessarily for Algerians like Messali). Just as often, the core issues were healthcare, the vote, pensions, and guarantees of minimum wage. The core claim, in short, was not so much a rejection of the bourgeois liberties of the European metropolis as an insistence that the rights of citizenship be extended to a wider community who had made their place in French republican space. Arguably, as Europeans today wrench their hands today about the fiscal costs involved in providing social guarantees and services–if not yet permanent residency or citizenship–to refugees or long-term residents from the Middle East and Africa, Goebel's re-assertion the issue of citizens' rights as "the substance of the vow of national sovereignty" is especially welcome.

As Goebel readily concedes, Anti-Imperial Metropolis opens as many vistas as it sheds light upon. Attendees at the book talk raised the issue–present but not central to Goebel's oeuvre–of the relationship between anti-colonial movements and the anti-capitalist language offered by both French Communists and the Soviet Union, on the one hand, and the socially-grounded language of citizenship and citizens' rights, on the other. Was the best way for marginal subaltern groups in the metropolis to demand the same bourgeois rights as French citizens (for some of them had fought in the Great War), or was it to reject capitalism altogether? As the case of Ho and Deng illustrates, in many cases the same people undertook an ideological amble from mutual aid to trade unionism to Communist politics as the best answer to their and their nations' plight at the hands of European or Japanese imperialism.

Likewise, as the presence (if not centrally so) of Syrians, Lebanese, Togoans, and Cameroonians in Goebel's story shows, the decades of Paris being "an anti-imperial metropolis" also coincided with French participation in the League of Nations – indeed, of France administering parts of the former German and Ottoman Empires as Mandates. For denizens of these polities, did the road to liberation go through Geneva (even if that meant a corrupt early decolonization à la Iraq), or through the language of social life and citizenship in the clubs, sporting societies, and mosques of Paris? (Goebel notes that for the denizens of the Mandates, the choice was empirically often for the former rather than the latter.) All in all, it speaks to the ambition of Anti-Imperial Metropolis that it intersects with some of the big debates–mid-twentieth century alternatives to the nation-state, whether in the form of federation, the League of Nations, or even the Negritude movement–on nearly every intellectual historian's agenda today.

As Goebel concludes, the world that he so vividly recreates in Anti-Imperial Metropolis had a shelf life. The Great Depression took the wind out of the sails in the French economy, and that meant that many subaltern denizens of the capital went home–home to the Algerian coast, to the Mekong Delta, or to the coastal cities of China. With them, however, they took not only memories of a Paris rather more shabby than the one evoked by Hemingway, or photographs of the Champs de Mars that, today, leaves the East Asian middle classes disappointed, but also new languages for making demands on imperial polities. In some cases, as with Messali, these demands would later give way to a new generation of radicals who would form some of the defining political movements of the 1950s and the 1960s, like the Algerian Front Liberation Nationale (FLN). In other cases, like that of Ho, the languages and entrepreneurial skills learned in Paris (and later Moscow) would come in handy for first dismantling French imperial rule and then a multi-decade war against the American superpower. And in still other cases, like that of Zhou and Deng, the lessons learned fighting back against capitalist exploitation and racism in Paris would be used to transform the lives of perhaps a sixth of the world's population–before, perhaps, being used again to transform formerly peripheral areas into the hubs of a reinvigorated global capitalism unimaginable at the time that the Great Depression sent these organizers and radicals back to Africa and Asia.

•

Even with Anti-Imperial Metropolis hot off the presses, Goebel is taking little time to sit back on his haunches. He has begun reading and doing some writing for a new project–on the comparative history of ethnic segregation in cities–that emerged from his reading for Anti-Imperial Metropolis. The plan, he explains, is to pick several cases from Southeast Asia and Latin America, investigating the history of ethnic and racial segregation as an intellectual problem in the making of cityscapes across the Global South. Such a project will also have the benefit bring him back closer to his original interests in Latin America – now, however, with his conceptual toolkit honed from reading the files of the French police, aware as no one else was of the ethnic archipelago across Greater Paris.

Finally, we ask Professor Goebel what has been on his reading list lately. Between finishing the book and his usual teaching responsibilities, he regrets, time for explorative reading within the discipline, much less outside of it, has been in sadly short supply. He notes, however, that he hopes to turn soon to Susan Pedersen's The Guardians, a book on the history of the League of Nations' mandate system and its role in the transformation of European empire published by Oxford University Press this year. (Should Goebel seek to get an overview of Pedersen's exhaustive tome, we'd add, he could consult our recent interview with Pedersen on The Guardians!).

For the moment, however, the book that should be on one's table is Michael Goebel's Anti-Imperial Metropolis: Interwar Paris and the Seeds of Third World Nationalism, published in the Global and International History Series of Cambridge University Press this year. We thank Michael Goebel for taking the time to speak with the Global History Forum, for braving the torrential rains to speak to the Harvard community of historians, and, above all, for writing a book that promises to change the way readers understand the role of Paris–that sometimes frustrating but still enchanting metropole–in the making of twentieth century global history.