On Empires and Global Cities: A Conversation with Anne-Isabelle Richard, Catia Antunes, and Cyrus Schayegh

By Dries Lyna, Radboud University Nijmegen

What role did cities play in imperial expansion and globalization? Despite massive urbanisation and a revolution in transport technologies and systems, did the modern period see a decrease in truly global cities? Have some cities become less global over time? What about global villages? Can we think of a small Dutch town “with families that drink coffee and have some cotton clothing” as a global place? These questions are at the heart of debates in the growing field of global urban history.

The Toynbee Prize is excited to bring you the transcript of the conversation that these questions inspired between four leading scholars with expertise in different world regions and time periods working at the intersection of global and urban history. They include the Global Urban History Project’s Dries Lyna Radboud University Nijmegen) and Cyrus Schayegh Graduate Institute Geneva), along with Leiden University’s Anne-Isabelle Richard and Catia Antunes.

Global Cities & Empire in the Early Modern Period

DRIES LYNA: To start off the discussion, I would like to posit a thesis: “all global cities in the early modern period were imperial.” Catia?

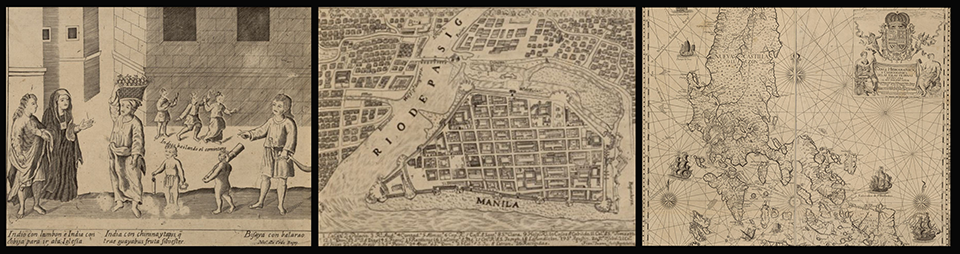

CATIA ANTUNES: The clear answer from my side to your question for the early modern period is: yes. I believe that the largest urban settlements in the world between, say 1500 and 1800, are imperial cities. There are two types of imperial cities: imperial cities that have been declared as such by a state or an empire, and cities that are large because they are the central stage for empire-building, which may be slightly different in terms of institutions and law. So, if you look at the European landscape, you would see very large cities like Amsterdam, Lisbon, Sevilla, Cadiz, or London being connected to empire, while I believe that very few historians in Europe would think of them as imperial cities. Once we think about imperial cities, we think of cities, for instance, in Asia, China, the Mogul or Persian Empire, and whatnot. I think it's important to nuance our thinking of imperial cities.

DL: Thank you. The nuance that we would like to bring to the table, then, is—and let me say it correctly now—while all global cities in the early modern period are imperial, not all cities and empires are global. That's an important nuance.

CA: It is. Cities may contribute to the global through scales of exchanges, such as urban networks, people, capital, ideas, or products, but they are not hubs or ‘gateways’—if you want to use urban history jargon—of either empire or globalization. If you want to think of it more concretely, I think that one of the largest imperial cities is Beijing, but the largest global connector in China is actually Canton. So, you see that an empire can have a very large city that is important in terms of networking trades, ideas, and the mobility of people over thousands of kilometres. But when you look at the globality of it, I would say that Canton is a far more global city than Beijing between, say 1640 and 1700.

The sizes of cities on the one hand and the direct relationship with the state that deploys empire on the other determine the role that these cities play, not only in the deployment of empire but also what they can take or give to the global world, so to speak. If you reduce the global lenses to Beijing within the Sinocentric world again (read here: China, Korea, and Japan), you see that the political core is still Beijing because the diplomatic and trade exchanges don't go through the ports; they go through the diplomatic relationships between Shogunate Japan and Joseon Korea.

Without the imperial centrality of Beijing, you would not have the possibility of the other globalisation, that is, more mobile globalisation of people, goods, ideas, or capital. I think that's the reason why the nuance is important. So that we don't expect that only formally declared imperial cities are global, but that all global cities are somehow connected to empire, even if the state does not recognise or label them as such.

CYRUS SCHAYEGH: Can I jump in very quickly? I think that, in general, and to perhaps strike a parallel in the modern period to what Catia just said, it's fair to say that there are also different types of imperial cities in the modern period. In the modern period, it is also correct to say that different empires interact and interface, and use and are used by cities, in different ways. I think that the point of the conversation today is not to come up with a unified, grand theory of empires and cities, but rather to talk about general lines while also being attentive to real differences between empires and cities.

Formal vs. Informal Empires

DL: Thank you very much for your intervention. I am looking forward to you looking backwards from your modern perspective to the early modern period; we will come back to the supposed discrepancies between the early modern and modern era later. In this respect, I would like to ask Anne-Isabelle whether or not we should differentiate between formal and informal empires or cities as part of formal or informal empires. Could you reflect on that?

ANNE-ISABELLE RICHARD: Well, I am hesitating, because I feel like my answer is going to be really short. Obviously, there are differences, but the body of literature on the whole concept of informal empire is so large by now, that, I wouldn't see a good reason why only cities that are part of formal empires could count as global cities. I do see the connection to empire as being constitutive of being a global city, but I don't think you need to focus exclusively on formal empire.

DL: Should we consider Geneva in the 18th and 19th centuries as a global city?

AIR: Thinking about Geneva as a city that facilitates a certain freedom of thought and creates this centre for Calvinism, attracting people from across the globe as well as spreading Calvinism globally, it might make sense to see it as a global city. So, again, we come back to the question of how you define a global city and whether you have different types of global and hyper-globalised cities. Does it need to match all the criteria of circulating goods, ideas, capital, people, et cetera, or can it also be primarily globalised in one or two respects and less so in others?

DL: Now we're talking about some sort of bandwidth that we can establish, in which cities can be placed on varying degrees of globalisation, from a minor effect of globalisation on the city's evolution to, for example, Canton, Amsterdam, Lisbon, or Rio de Janeiro if you will. I think we can all agree that we would define most of these cities as being global cities.

CS: Let me add one element here. I think the question is not only how we define what starts to count as global or define certain themes as having to be necessarily present for something to be called global. We can also talk about the difference between, let's say, objective structures versus subjective perception.

We can partly use a structuralist analysis to talk about what is and is not global. At the same time, I think we can talk about subjective perceptions, and Geneva may be a really good example. Calvinists believe that Geneva plays a very central role in the broader realm of theology. It's a new city from which to create a new religious world. We need to pay attention to this subjective, perceptional element in addition to everything else.

DL: You really got me thinking there. I have to admit that I was going down the structuralist road and thinking about hubs, networks, and flows of people and goods. Maybe the distinction between a direct and indirect influence could also be helpful here to reflect on the impact of globalisation.

Small villages in the Dutch hinterlands hardly ever got in touch with the flows of people and ideas, but some of the products from the colonies do wind up there. How global, then, is a small village in the hinterland with families that drink coffee and have some cotton clothing? I think we can all agree that it’s not a global city, but what's the bandwidth of globalisation like over there?

AIR: You can write a global history of a random village because they produce and contribute to something global, but they wouldn't be global cities. Likewise, you can write a very parochial history of a global city. I think that Geneva is in yet a slightly different category from discussing hinterlands. The question becomes more what categories you need to constitute a global city. As Cyrus points out, in the religious realm, Calvinists indeed claim Geneva to be global. You could also talk about the extent to which Rome is a global city throughout history, just because the Vatican is there. Rome becomes relatively tiny at a certain point in time, where it's clearly not the centre of the world, except if you think about the church. I guess that's a different, less obvious way of viewing globalisation. I’m sure there are similar examples from elsewhere that we could think of.

CA: I think it might be useful to also make a distinction—or at least reflect upon a slight distinction—between what it is that cities generate that are global and whether the presence of global things actually means that the city as an urban environment is global. I cannot put my head around the idea that Geneva or Rome, for that matter, are global places around 1750. They produce a specific environment that enables a specific global development that is not a global urban development, but a global, ideological phenomenon.

It's pertinent to ask the question: Are these global, ideological trends always coming from cities? Not necessarily. In Islam, we know that it is not the case. In some parts of Buddhism, we also know that that is not the case. I think it is an interesting question to ask whether a non-global city can produce a changing global movement. I think it can. The largest mobility globalisation in the nineteenth century is not even produced by cities. Cities are turning points to ship people off: the Italians, the Irish, the Middle Eastern, the Eastern Europeans. We may want to reflect on these issues collectively.

Less Global Cities in the Modern Period

DL: I think you're giving us a nice bridge to gradually move into the nineteenth century. I’d like also to give the word back to Catia. In the modern period we see a growth in urbanisation with more cities than before. But according to what you put forward as the variables of globalisation, these cities were less global and more specialised than before.

CA: My argument is that of course, you have a whole transition from pre-modern growth into modern growth, and from immersion to industrial capitalism. But from a very social and economic history point of view, when the industrial revolution hits western Europe and you get to the globalising, liberal 19th century, the speed of urbanisation mostly starts in the western world and spreads elsewhere.

The problem here is that the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century does two things. Countries develop strong, large-scale economies. That means you have quick industrial urbanisation with a lot of industrial development in cities that are not that large. Lancashire, for example, is not known as a large city in the UK. The same goes for the industrial issue in Belgium and in Germany. So, the first and second industrial revolutions are not happening in large cities: these are small cities of modern economic growth that are not going to be global leaders in terms of capital transactions or even redistribution centres.

What they are, are huge globalisers of labour. Usually, you have specialisation for production in small cities, with two or three hyper-globalised cities, where financial services or the tertiary sector and everything that comes with it, are allocated. You see this from Lancashire into the city of London, into New York. Obviously, London and New York do not produce anything for the industrial revolution. These are the global cities. This is very particular and, in this sense, I think this nineteenth century is the exception rather than the rule, even though we always look at the nineteenth century as the start of the modern world.

The first and second industrial revolutions are not happening in large cities: these are small cities of modern economic growth that are not going to be global leaders in terms of capital transactions or even redistribution centres. What they are, are huge globalisers of labour. Usually, you have specialisation for production in small cities, with two or three hyper-globalised cities, where financial services or the tertiary sector and everything that comes with it, are allocated. You see this from Lancashire into the city of London, into New York. Obviously, London and New York do not produce anything for the industrial revolution. These are the global cities. This is very particular and, in this sense, I think this nineteenth century is the exception rather than the rule, even though we always look at the nineteenth century as the start of the modern world.

Once you specialise, you lose the ability to be global, because you're not serving the principles of the central city of the network. You are a cog in the machine, but the machine is elsewhere. That’s where my argumentation arose from. Yes, there's an explosion in urbanisation. Yes, there is hyper-globalisation in the 19th century—it's the liberal century. But the amount of real global cities that you have by, say 1900 or even 1850, has decreased in number.

I also believe in the diversity of regional impacts, as the urban balance falls into the West during this time: these global cities as the centres of modern, economic, and industrial growth are all in the West. Again, this does not mean that there are no important smaller cities in contributing to the global development of specific trends of migration, ideas, cultural movements, or environmental change, but those smaller cities are not global. And again, when we get to the Geneva-Rome discussion, you can have global things happening in places that are not global like you can have global cities that are not actually contributing much towards modern growth, except, for instance, with their tertiary sectors.

It's counter-intuitive to a certain extent, which is why I think we need more reflection and we might want to very simply start counting how many people live and work in these global areas from the 19th century until the First World War. It's not because quantity matters, but because I think that you would be shocked with regional diversity, with very global cities in Asia or the South Atlantic by 1700 which are not global cities anymore by 1900, as they're cut off from a lot of the global decision-making.

CS: This is a most interesting issue. I partly agree, but mainly disagree with Catia, which, I think, is the great thing about having this conversation. Having this disagreement works so well, but let me just say why in a couple of bullet points.

The first thing I’d say is that one thing underlies industrialisation, which is sort of the key trigger that Catia identified: very broadly speaking, technological change. And not simply change, but rather the advent of mechanised production, which has an effect, not only on the production itself but also on transport, as we all know. It's of course true that not everything immediately becomes a steamship. There still are lots of other transport technologies, from horses to normal boats, et cetera. But transport starts to change and that, in turn, means that the world becomes connected in a much faster way than it used to be before the 19th century. I entirely agree with Catia that this one effect does in part lead to a concentration of certain functions, because this is now possible in fewer cities; greater networking leads to the possibility of a greater concentration of functions.

However, first, I would say that a city like Singapore by the late 19th century , other than with the production of mechanised goods, is just as global as a city like London. Singapore has its secondary sector and there is a tertiary sector. That is, if we just go with the economy―because we could go for all sorts of different themes of globalisation―I would also never call these cities global cities, but, more specifically, global gateways. Catia has mentioned this before and I think it makes a lot of sense.

The second point I’d like to raise is that, at the same point in time that there is hyper concentration, there is also something else: a greater integration of more population centres than ever before into a worldwide system, not simply of goods, but also of ideas or movements. I think we can call these population centres global cities as well. They are just not global hubs. There are now more people whom we know are migrating somewhere else. There are more goods that we produce, send away, and receive than we did before. More ideas are circulating in all sorts of different structured ways than ever before. So, I think we can talk about more global cities, perhaps even globalised villages, or global villages.

There are two things that happen at the same point in time, then: the stretching and multiplication of the global in more population centres than ever before, and a hyper-concentration. However, I think this development cannot be simply located in the Atlantic World but goes far beyond. There are a few other cities that I do think can be called global hubs and gateway cities. I want to add the empire issue to this, but maybe we can do this later because that opens up an entirely different can of worms.

AIR: I would just like to ask Cyrus about global villages, which he mentioned at the end. I am curious: how would you see global villages relate to global cities? Is this the hinterland that we discussed before?

CS: Let me give you an example. My geographical area of expertise is generally speaking the Middle East, and Greater Syria, which is Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Israel, and Jordan, a little bit more specifically. In the late 19th century, you have a surge of immigration from these areas to Africa, Europe, and specifically to the Americas. Then, you have a greater integration into the world economy of different small villages. You have many more people who now are in contact with others in America, remittances that are being sent back, new social ties, new goods that are being consumed alongside new ideas. All of these changes, in one way or another, I think, need to be reflected on. How do we think about these villages? I wouldn’t call a village a global village, just because it plays a huge role in the global economy. That would—of course—be wrong. But we can think about these villages as global places, or as places that are networked into the world because of all the things that I just mentioned.

AIR: I understand, but isn’t that more like writing a global history of villages x and y?

CS: Mainly, but only because, for instance, marriage ties continue to matter. In a certain sense, this village, which before was of local and perhaps regional importance, all of the sudden has a more global presence in social ways, or maybe even literary ways, because of new journals for example.

AIR: I mean, it's also a question of how much you want to focus on global cities and whether you then also want to show the connections to and repercussions of global cities are for other localities. During the 19th and early 20th centuries a lot of terrain would be covered by this. I wonder: where do you want to draw the line? I can understand what you're saying about these ties and the circulation, but what does that do for the concept of the global city?

CS: I don't think there is a line to be drawn where beyond that line you are global and before you're not. I know you didn't mean that, but I rather think that it is like a continuum, just to piggyback on one of the terms Dries mentioned earlier. Some villages are still cut off from whatever we would call a global network, while other cities are totally tied into it, and then some cities are located on different points along this continuum. I think that's how we need to think about globalisation. This interesting also because it also interferes with changing regional patterns of interaction, not simply inter- but intra-regional. Where you are on this continuum affects how you function within your own region. You didn't talk about this separate issue, and I don't want to go down that rabbit hole, but I think it's another really interesting idea to behold.

Empires & Global Cities

DL: We haven't really talked about empires; we have talked more about globalisation in the long stretch and how that influences urban development, how we have to place urban localities of different sizes on some sort of bandwidth of globalisation, and then there’s Catia’s remark to question whether global cities—however we define them—have to be placed on the bandwidth at all, or whether they are reserved in a separate category.

CS: Let me pivot exactly to this issue of empires and make a very generic argument. It seems to me that in the 19th century and into the early 20th century, we can make a rough and ready distinction between two different types of empires. One type is what we used to call ‘land empires’, which are mainly Eurasian empires, and on the other side, we have ‘maritime empires’ which are principally the European ones. It appears to me that the latter concentrated more functions within a smaller amount of places to boost political and commercial activities. I think Frederick Cooper once called it a ‘capillary way’.

Think for instance of Dakar, in French West Africa, just to give an example of a maritime empire. Certainly, it's a global city by the later 19th century. In Eurasian land empires, and certainly the Ottoman Empire, partly for political and commercial reasons, the imperial government has an interest in diversifying functions. So, in the Ottoman Empire in the later 19th century, for instance, had Istanbul, but also had to accept and actually nurture the explosive growth of Beirut. The latter basically becomes the biggest city not in population, but in terms of its commercial and cultural influence in Greater Syria. This helped Western actors, which in turn scared the Ottoman elite.

At the same point in time, and partly to balance the power of Beirut, the Ottoman elite politically and commercially backed the big cities in the hinterland: Damascus and Aleppo. The case of Aleppo, in particular, meant that older commercial ties to East Asia became much less important. But Aleppo didn't just fall off the map. It continued to be an important commercial, cultural and administrative centre in the Ottoman Empire. I can't say too much about other Eurasian land empires, but it appears to me that, for different reasons, political elites have a stake in trying to keep more than simply one city around, while in maritime empires, in particular in multi-colonial regions such as West Africa, this is perhaps less the case.

AIR: I do think there is a distinction between land and maritime empires, but I wonder whether that is the only one. But French West Africa was also a specific case and I wonder whether it also has something to do with the way this particular empire operated and how the French arrived and progressively conquered the hinterland and the way that worked for the Ottomans. I was also thinking whether this had something to do with empires after the scramble for Africa and those that came before. I’m not sure that it's just about maritime versus land empires, or whether it has something to do with a similar but perhaps conceptually slightly different way of conquering neighbouring territories.

I am thinking about the trope of the Ottomans as the sick man of Europe and Frederick Cooper and Jane Burbank's terms of ‘empire is governing different people differently’, and whether or not if you are experiencing some sort of imperial overstretch you have to operate in the way you describe. I don't have an answer here, but I’m trying to think through other approaches to what you describe. I do agree that Dakar was clearly the biggest hub in French West Africa, but if you think about the whole of West Africa, so also including what becomes part of the British Empire, it's less obvious what the centre would be. Not that long ago, in terms of for example higher education in the whole of Francophone Africa, Dakar was a centre that even reached as far as Madagascar. But this may say more about France and the role of Paris, but that is a different discussion!

CA: I think we can keep conversing for the coming years and it's very exciting, actually, that we don't agree. That's what makes us interesting as historians. Our source material also matters: how do you come up with your queries? Are you thinking from the point of view of the city, or are you thinking about the impact of something that happens in a specific locality has in the world? I think it matters to talk about global cities or global things that happen and their connectedness within urban spaces, which, in my view, are two different things.

I would perhaps just like to raise one point that we did not talk about, but that's particularly important when you think of empires related to urbanity: power. The whole point of imperialism, of colonialism, is that one of the most pernicious changes we see in world history, from colonialism into imperialism, is the share of power that was still not yet controlled by the heads of the empires and allowed these global cities, connected to empires, to proliferate until after the age of revolutions, because the power of the imperial state rises in such a manner that it curbs the power differential between state and city.

Are you thinking from the point of view of the city, or are you thinking about the impact of something that happens in a specific locality has in the world? I think it matters to talk about global cities or global things that happen and their connectedness within urban spaces, which, in my view, are two different things.

In my view, Singapore was far less global by 1850 than it was in 1750, because London has changed this power differential in such a way that there's no way for Singapore to actually function without London in terms of institutions. Financial institutions are particularly pernicious in this sense and I think that these power differentials, connected to empire and the transition from colonialism to imperialism, are going to strangulate the regional diversification. The spreading of global cities connected to empire in the early modern period was something the modern period tends to eradicate: Dakar may be a fantastic global African city, but Paris still commands what happens in Dakar.

Speaking of power after the age of revolutions and of the power of the nation-state as the red thread that commands empire, matters in determining the globality of cities. Again, it doesn't mean that Dakar and Singapore do not contribute to globalisation, or are not influenced by it, but they do not command the global. My point would be to be wary of political state power and not trust everything that has been written on this topic. Power also matters after the age of revolution, even in China. To a very large extent, even, because of the way Western imperial powers deal with China. The same goes for the Americas in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

DL: I’d like to thank all of you very much for sharing your expertise. For anyone interested in more in-depth analyses of what we've talked about I would gladly refer to the journal Itinerario, which touches upon these topics with individual case studies as well as with special issues. I would also refer to the publications of the panel members, and what the Global Urban History Project has been producing. For example, last year founding GUHP-members Mariana Dantas and Emma Hart co-edited a special issue of Urban History on early modern cities and globalisation. Next to that, GUHP started a new series with the Cambridge Elements in Global Urban History, edited by Michael Goebel, Tracy Neumann, and Joseph Ben Prestel, that touches upon a lot of these topics in a very thematic manner.

***

The Global Urban History Project (GUHP) was founded in 2017, and brings together scholars working on the crossroads of urban & global history. Its goal is to encourage the study of cities as creations and creators of large-scale or global historical phenomena, thereby minimizing the Eurocentric and U.S.-centric focus of urban history, while also connecting early-modern historians with those who work on more recent periods. In 2020, GUHP started a mentorship program that connects emerging researchers with more established scholars. Last year, we added ‘dream conversations’ to the roster, in which we discuss current and future topics that are relevant in global urban history. This interview features within the ‘Cities, Empires, and (Dis)Contents’ conversation theme.

See https://www.globalurbanhistory.org

Itinerario. Journal of Imperial and Global Interactions (published with Cambridge University Press) has been at the forefront of the global turn in critical histories of empire and colonialism.