Plowshares into Swords: An Interview with David Ekbladh

As much as it was a moment of America’s reckoning of its own immense power or its sudden vulnerability, the early-1940s was also a moment of a successful transplantation. Technical experts of the League of Nations were shipped (literally in a Pan Am Yankee Clipper) across the Atlantic and were soon incorporated into America’s war effort and postwar planning. Their knowledge on food, public health, world economy, and many more was weaponized, first, to win the war against the Axis powers and later, to “win the peace” against the Soviet Union.

How was this transfer of knowledge possible? According to David Ekbladh’s new book, Plowshares into Swords: Weaponized Knowledge, Liberal Order, and the League of Nations (University of Chicago Press, 2022), it is essential to understand the US’ special relationship with the League during the interwar years. Contrary to being skeptical outsiders, many Americans were dedicated insiders; they intermingled with fellow liberal internationalists to exchange ideas to address what they conceptualized as common global problems brought about by industrial modernity. In essence, the successful transplantation of internationalist knowledge at the onset of the Second World War was feasible because it had been nurtured over the preceding two decades within the liberal international society of which the US was an integral part. As Ekbladh points out in the introduction, “American internationalism was, well, international.”

During the course of the conversation, Ekbladh expanded upon his views on internationalism and hegemony, the role of internationalists from “non-Great Powers” in the liberal international order, and the place of democracy and planning in the thoughts of the interwar liberal internationalists.

- Seokju Oh (Columbia University)

OH: Can you tell us how you came to write this book? You say in the Acknowledgments that “this book is a happy accident.”

EKBLADH: Yes, the “happy accident” was that I had this opportunity to go to Geneva to explore a few elements that had come up in my research for another book. Initially, I was looking at how US views of the world and its posture toward the world changed in the interwar period, particularly during the Great Depression, and I saw connections to the League of Nations. Once I was in Geneva, I began to discover that there were, in fact, something more than connections. Not just the fact that Americans were using the data and analysis emerging from the League, but that they were actually influencing it from within.

You know, this is a while ago -- I mean over a decade -- and a lot of the studies on the League that are familiar to us now were just germinating back then. It was particularly exciting to dig deeper in the archives to find out that there very much were American figures and institutions that contributed to the League. The research began to lead me to something bigger, something different from the book on the interwar origins of US globalism that I was working on, and I realized that there was another project there. A few other “happy accidents” happened. I also got to spend some time in the South Pacific. This did not come out of my professional trajectory but my wife’s—she was running a project out that way. It allowed me to be near some materials in Australia and New Zealand that many scholars working on these issues have not explored and they added further facets to the project.

Sometimes the archives do reveal things, but in my case that was coupled with, personal journeys along with shifting scholarly inquiry.

OH: One of the phrases that reappear throughout the book is “means to an end”: information as means to an end of social betterment; international organization as means to an end of international society; and history as a usable past, again, a means to an end. What kind of end do you envision this book to serve?

EKBLADH: The phrase was intended to get at a sense that liberal international society is always looking for tools. Liberal international society is a framework that people, including myself, impose over a collection of institutions and individuals. It’s not a thing with a mind of its own.

When confronted with challengers or problems, various actors historically look for tools, analytical and otherwise, to contend with problems. That was true in the 1930s and 40s. It’s true today. What I was trying to pull out was something different from what the standard political narrative tends to assume: that there were these analytical tools out there for social betterment or building institutions that then were pitched to the US as part of the war plan during the Second World War. My aim was twofold: to get at the broad array of tools that various actors have used historically to deal with challenges of building and maintaining international order and to point out the importance of knowledge and analysis in constructing those tools by focusing on the ways in which their creation frames interactions among various individuals and institutions.

What I would love this book to do, in many ways, is to get us to not only ask questions about generalities I just talked about, but also consider how the US is situated within international and global dialogues. I wanted to point out that it’s not as simple as the US at certain points deciding the way global affairs are going to be shaped. In one way, I hope to open anew the discussion about post-World War II planning and even some aspects of US public policy by showing there was an important international dimension to it.

Finally, this is not a “League” book. When I say “means to an end,” what I’m doing is, in some ways, diminishing the League. The League looms large for a lot of internationalists, but push comes to shove, they’ll tear it apart, take the pieces they like, throw away the rest, and build something totally new. What I hoped to say is that some of the older ways in which we’ve looked at America’s place in the world don’t hold up when you realize that American policymakers of all sorts engaged with issues within a wider international context.

OH: The book seems to argue that international cooperation, regime, and norms preceded US hegemony and their intertwining with it only came afterwards. In that sense, the book’s title could have been “Before Hegemony” -- to flip the title of After Hegemony, a classic written by a liberal institutionalist Robert O. Keohane.

EKBLADH: That’s a good way of thinking about the book, though I wasn’t thinking of it as explicitly engaging International Relations (IR) theory.

One of the things I was attempting with hegemony was to complicate some of the narratives about American internationalism. A cheeky comment in my book that you like -- “American internationalism was, well, international” -- was to remind today’s scholarly discussants that American internationalists were not just interacting with one another. They were also interacting with other figures outside the US. That’s a fundamental characteristic of their internationalism.

These interactions gave access and influence to these figures from outside the US, but it also meant that they could at points of crisis be coopted. One of the things that, I couldn’t come down clearly on -- and I must just acknowledge that there’s a tension -- is that there is a line between influence and cooptation. These international figures like the New Zealander economist John B. Condliffe, who interacted with Americans and many others through what we would now call civil society organizations, had a view that the US is the coming power; and that we need to acknowledge this and work with US power. Partly, this is what drew Condliffe to the US, and it wasn’t as simple as the Americans saying “Ah, he’s a useful idiot and we’re going to coopt him.” His own understanding of US power was part of why Condliffe integrated so easily into a whole set of American institutions over time. Not because the Americans were prompting him to, not because he wanted to ingratiate himself with the Americans, but he was saying something that came out of a logical analysis he had conducted.

There are others, particularly among smaller actors, who understood what the US was and what American power means for not only international politics but the international economy and thereby concluded that they needed to work with the US. In some ways, this was an accommodation to US power; in other ways, it was a move to shape it. These actors used these tendrils of international society to work their way in and get their ideas seen and heard. Their American counterparts were happy to receive them, partly because they didn’t have many of these resources and capacities (and you know, the limited capacities of the US government and even civil society are particularly apparent during World War II). It’s that much easier because these refugee internationalists say things that are easy for the Americans to hear, agree with, and coopt as much as the fact the US was able to trade off and share burdens with these actors.

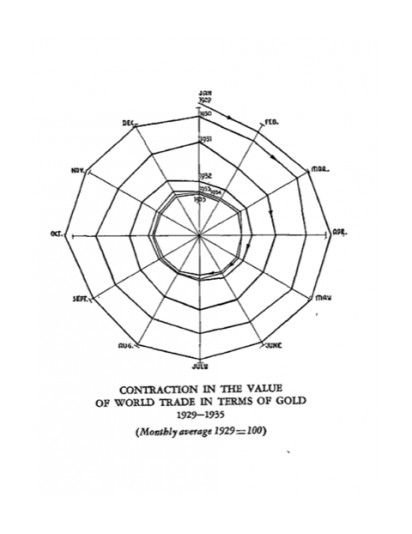

The “spider’s web”: John Bell Condliffe’s visualization of the collapse of world trade, constructed with League data that has become an enduring representation of the collapse of the global economy. (World Peace Foundation)

OH: Speaking of Condliffe, then, how does the role played by actors from small countries (or what is today called middle powers) complicate our understanding of the US’ worldmaking efforts in the twentieth century?

EKBLADH: Well, the point is not to say the US was not stepping out to remake the world or not explicitly beginning to acknowledge its own power and put policies and structures in place to enhance its position. It was.

But the point I want to make is to say, “let’s look at where some of those ideas and some of those elements are coming from,” and -- to be a little bit of an IR scholar here -- ask “why did some smaller states accede to some of this.” The discussions that these international figures participated in weren’t necessarily emerging from, say, within a ministry; they were not necessarily official. They were coming out of a longer and larger dialogue about global problems. What the US was embracing when it first began to embrace internationalism, even before the United Nations Organization, was the institutionalization of a lot of technical ideas for dealing with global affairs. Some of the best examples are obviously from the League, but not solely.

It was very easy for ideas about nutrition or nascent models of economic development to travel into the very center of US power. Of course, this is not to say these ideas and other ideas were not already there, but the ideas generated by international figures very easily reached Roosevelt, not just Henry Wallace and Sumner Wells, and easily moved into the realm of international policy formation and then to institutionalization.

All this amounts to a need to see some aspects of US hegemony as, at the very least, connected to some of these larger transnational debates. This takes us back to the question of what I want this book to accomplish. When asking questions about what the US did and why, we don’t have to throw out everything else other than the plans and ambitions that are emerging from discussions within the US. I think one of the points I make in this book is that postwar US hegemony itself was a sort of international organization in a general sense. More to the point, the US was not the sole voice. There were also many individuals from outside the US involved in the discussions about what should be built after the conflict. They didn’t always buy into the US’ vision of its own hegemony. Yet they acceded to US power, because it seemed to be capable of doing the types of things that they themselves thought as important for liberal international life to function.

OH: In relation to the reform efforts of the League in the late-1930s led by the former Prime Minister of Australia, Stanley Bruce and prominent Norwegian conservative Carl Hambro, you do seem to make a more specific argument than what you just said. I mean, the book suggests that these international figures from smaller countries consciously remade the League into an organization of technical expertise so that it can become palatable to the US, a Great Power.

EKBLADH: Well, I think it’s actually two-sided. In the book, I do push very hard on the argument that gestures are made to connect the League to the US. League officials and partisans are literally saying this. Avenol, the second-to-last secretary general of the League, says explicitly that he’s trying to lure the US into the League with the bait of technical cooperation. They put considerable effort into creating the image of the League as a technical service provider. That is a political move. Some of the people dismiss the League’s emphasis on technical expertise -- there were even people at the time who dismissed it -- and say that was just the League looking for some kind of rationale for its existence. There’s an element of truth in that.

But I do think, when you get down to the level of some of these figures, you get to see that they’re not just trying to justify a nice job in Geneva. They’re actually saying, “look, the League is providing a service; it is a focal point for activities on key issues, and their service is either unsurpassed or nobody else is doing it.” In the 1930s, that claim was often very true, and that was therefore a legitimate rationale. This was the reason why the US and many other countries were paying attention to the League. It wasn’t just that these technical experts, say, these economists, were saying that the League is important because it is doing something important in their fields. There were policymakers and many others who had this strong understanding that the League was providing a unique window on economic activities. This was particularly important in the 1930s where the world economy is a basket case.

And here you’re hitting on the bridge between the plowshare and the sword. In the context of the Depression, this is the plowshare, helping us understand how the world economy works; giving us data and studies that show us how we can work on the “standard of living.” For the Americans, this experience feeds into their understanding of how elements of international affairs, for want of a better term, fit together. In the context of the Second World War, the same sorts of economic data and analysis have dramatic implications for the politics of the that war, particularly the politics around the postwar reconstruction. These international figures and their associates in the US already un that their expertise is the very technical tool that can be used for governance of global concerns. They can be used to promote peace or they can be used to prosecute a global war.

OH: I also want to connect your book with other books that deal with the thinkers and practitioners of world economy. I have in mind Quinn Slobodian’s Globalists or a more recent book by Jamie Martin, The Meddlers. What relationship did the liberal internationalists who appear in your book have with democracy?

EKBLADH: I have read Slobodian’s. I think it’s excellent. He is looking for the history of neoliberalism, and I’m not. I would say, though, some of what the Miseses and Hayeks are reacting to in the 1930s and 1940s in some of their writings is this community of people affiliated with the League who are basically saying “if we can perfect our statistics we’ll be able to solve many of our problems” (I also want to be careful here because this line gets parodied by later generations as bland positivism.) Simon Kuznets, whom I talk about in the book, is connected in various ways to this. Loveday too. They are, of course, very aware that they’re trying to build things from crooked timber. The neoliberals Slobodian is talking about are starting to see the liberal internationalists around the League having a sort of bacillus that will eventually become full blown totalitarianism. On the flip side of that debate, I see some of these figures, like Condliffe, also arguing with the neoliberals or those associated with the Colloque Lippmann. Many liberal internationalists accepted economic planning but were concerned about it becoming an end run around parliamentary structures. There was a sense that all this planning must be rooted in democratic and liberal life.

One of the reasons why I’m perhaps a little more patient with these historical figures – even though I don’t want to indulge them too much-- comes from the fact that a lot of them were wrestling with the imperfections of the system. I especially see that sensibility expressed by Loveday who has these wonderful correspondences with people from the Rockefeller Foundation. (It should be a reminder that these people are in an interesting middle space where they have influence, and they can and do see the politics surrounding them; it’s one of the reasons I don’t tend to like the term technocrat.) They’re having these discussions about the dangers of totalitarianism, how modern societies respond to upheaval, and how should we be concerned about this or that. These are the big, pressing issues of the day and they have their own complicated, even messy views of them. It’s a reminder that they’re wrestling with some issues that maybe we’re coming back to today.

I think what sometimes gets overlooked is that these internationalists were contending with the problems of industrial modernity and very aggressive states with different systems -- fascism, militarism, and communism and sometimes groping for solutions in the moment. That doesn’t make them the good guys, but it does make them, I think, a little more complicated than sometimes portrayed.

OH: Can you tell us more about your interpretation of that complexity of the liberal internationalists -- how they were for planning, yet skeptical toward states?

EKBLADH: Yes, that’s a hard one, because some of that complexity is not as explicit. What is my understanding of all of that? These figures are part of the conversation about how strong the state should be involved in aspects of life.

These liberal internationalists in the 1930s shared an assumption that the marketplace, or for the lack of a better term, capitalism, has gotten us into this mess -- or laissez-faire has gotten us into this mess -- and the state needs to be a guiding hand. But they also think the state itself is potentially dangerous. Particularly, if you’re in Geneva, but also anywhere, you can look around few hundred miles to Italy and Germany. From that vantage point, it is clear from those regimes what going too far with the state can get you. I think they were trying to kind of square that circle. The state should plan, but like Condliffe said, one must be careful about the state going too far out and around the representative parts of government.

If I may add I think, and this is a personal view and a general view, a lot of people in politics and policy are looking for solutions in their present, although this not to let them off the hook for long-term impacts. They are not looking for a perfectly articulated intellectual system to work, and neither are policy entrepreneurs. I think the basic attitude was “we should have planning; the state should have a bigger role; but how far that goes -- we’ll leave that up to something else.” Sometimes, as historians, we expect these actors’ view to be coherent or clearly spelled out and sometimes establish more clear continuities than actors at the time could see or intended. Also for some of them, and this is a suspicion, laying their positive views about the state too clearly in a policy memo or a book is avoided in the era. That’s just my own reading between the lines.

OH: Here is the closing question: what’s your impression of the cover of your own book? The book is about liberal internationalism, but the cover features “Let Us Beat Swords into Plowshares,” a sculpture in the United Nations Arts Collection which was a gift from the Soviet Union!

EKBLADH: I do love the cover. I can’t take all the credit for it, but it is a fascinating connection you bring up. To be honest, initially I tried get the press to do something around what’s become the Kindleberger Spiral -- what Loveday more evocatively called the “spider’s web” -- which has become a defining global representation of how a Depression became the “Great Depression.” As for the cover that emerged, I like that there’s some ambiguity of what this figure is doing. It’s known to be a depiction of a person bending a sword into a plow, but in certain context he could be straightening a plow into a sword. One of the aspects of the book is that for these liberal internationalists it was easy to toggle between discussing how to reform the world economy through global collaboration and then turning those very same ideas and analyses into propaganda to justify war aims or provide useful knowledge for economic warfare. That knowledge can very easily be bent from one thing to another in very little space and time and then bent back is something we don’t often consider. That fickle quality of information and analysis is quite well represented by the cover.