Guns, Spies and Empire, Or, Why Good People Do Bad Things: An Interview with Priya Satia

U.S. power today relies on sophisticated global surveillance networks, which the world is keenly aware of but rarely sees. In Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural Foundations of Britain's Covert Empire in the Middle East (OUP, 2008), Priya Satia explains how it became possible to possess an empire that was both vast and possible to ignore—how an empire could hide in the skies. Her account is not a story of the United States in the last half-century, but of Britain in the first decades of the twentieth. Through what she defines as a cultural history of intelligence, Satia traces how intelligence agencies came to wield unbridled executive power.

U.S. power today relies on sophisticated global surveillance networks, which the world is keenly aware of but rarely sees. In Spies in Arabia: The Great War and the Cultural Foundations of Britain's Covert Empire in the Middle East (OUP, 2008), Priya Satia explains how it became possible to possess an empire that was both vast and possible to ignore—how an empire could hide in the skies. Her account is not a story of the United States in the last half-century, but of Britain in the first decades of the twentieth. Through what she defines as a cultural history of intelligence, Satia traces how intelligence agencies came to wield unbridled executive power.

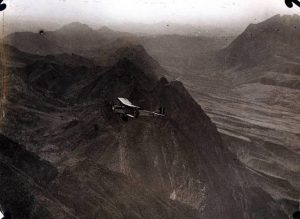

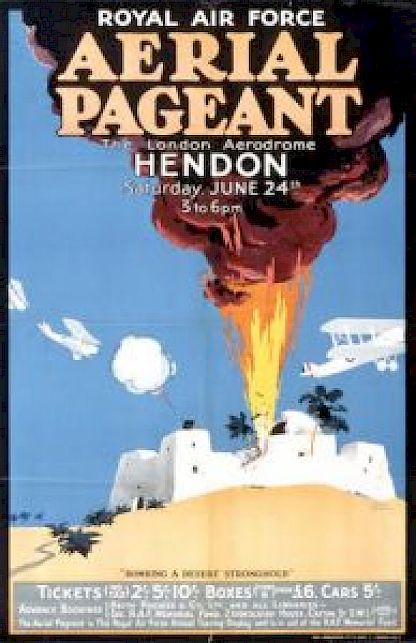

Satia argues that the making of Britain's "covert empire" was bound up in intelligence-gathering tactics pioneered by British agents in the Middle East (Arabia and Iraq, specifically). The ultimate tool of covert empire—aerial surveillance—came to be used far beyond the Middle East; but, Satia argues, its initial deployment there resulted from the marriage of a cultural epistemology peculiar to British agents in Arabia with the emergence of mass democracy, and a new suspicion of empire, in Britain itself.

Priya Satia's second book, Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution came out this month with Penguin. I sat down with Satia to discuss Spies in Arabia, how she got from writing about spies in the twentieth century to guns in the eighteenth, and her commitment to writing history that people will read. Satia received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, and is now Professor of Modern British History at Stanford University. She teaches courses on Britain and its empire, particularly in the Middle East and South Asia.

–Chloe Bordewich

CHLOE BORDEWICH: Where did your idea for Spies in Arabia come from?

PRIYA SATIA: I had an interest in South Asia before I had an interest in the Middle East. I was looking into the Indian Army, which did most of the fighting in Iraq during World War I, and became distracted by the Indian Army's British officers. They arrived thinking that they were in the land of the Arabian Nights, that this place was mysterious and unknowable. But they were there to perform very practical tasks. I became curious how their cultural outlook shaped what they did and how they did it.

When I got to the National Archives at Kew, without much training in what to expect, I didn't know where to start. So I began with A because it was the beginning of the alphabet, and I opened the Air Ministry files on Iraq. I discovered that there was something called air control, and it was invented in Iraq. I started to wonder if I could draw a line between the British officers who felt they were in a fog, unable to know anything, and the hyper-surveilling air control regime ten years later. So I hunkered down to make sense of the archives—the Air Ministry, Colonial Office, Foreign Office, and personal papers of the key players involved before, during, after the war. What if I had opened the Admiralty files first? The project could have been very different.

BORDEWICH: You make the case in the book that British intelligence agents' mystical conceptions of Middle Eastern, specifically Arabian, culture were so significant as to stimulate the development of a new approach to information gathering, the "intuitive mode." Why was Arabia any different from other parts of the British Empire—India, for example?

SATIA: The British had an Orientalist outlook toward India, too. India was exotic, exemplified by the trope of the bazaar. But in the Middle East at the turn of the twentieth century, there was a particular Orientalism centered on the desert. Its deceptions and apparent infinitude, in their view, made the desert much more challenging from an intelligence point of view than India. The British also became interested in Arabia later, at the turn of the twentieth century, at a time when intelligence itself was becoming a kind of science. The conjunction of these factors at that particular time made the Middle East different. These British agents concluded that "Arabia" could not be known empirically; it had to be known intuitively. And only those who had spent enough time there, in the desert especially, would be able to "think like an Arab"—to understand the place intuitively.

BORDEWICH: In other words, we can't understand spying without a fuller picture of the epistemological universe in which spies operate. How was the development of intelligence gathering linked to contemporaneous trends in science and philosophy?

SATIA: The nineteenth century saw a celebration of empiricism and rationalism, but by the end of the century, an influential avant-garde culture in philosophy and literature emerged in response, arguing that empiricism and rationalism could only go so far. Scientific discoveries of the time seemed to confirm this—the encounter with invisible forces that made things like radio communication possible. There was a growing interest in the occult, because if you can communicate wirelessly, you might also be able to communicate with the dead. Those who were gathering intelligence in the Middle East were influential in this culture, and influenced by it in turn. It's all part of the same cultural backdrop, a willingness to suspend disbelief.

BORDEWICH: Spies in Arabia is very much a human story as much as it is a story about the state. Everyone knows T.E. Lawrence, at least Peter O'Toole's version of him. Are there any other stories that particularly captivated you while you were writing this book?

SATIA: The Philby story is very interesting. St. John Philby came out of an Indian milieu, born in Ceylon, then became a Middle East expert. He really absorbed orientalist notions of Eastern fatalism, to an extent that really, practically guided his life decisions. He had a vision for himself of an almost Christ-like journey, in which he would repeatedly be banished. And he fulfilled it, over and over again. Eventually he defected to Saudi Arabia. His decisions and outlook also shaped the fate of his famous son Kim, whom he named after Kipling's novel about a boy spy, Kim. Kim Philby became the most notorious of the "Cambridge Five," the group of high-ranking members of British intelligence who were Soviet moles. Kim's story in turn became central to how, culturally, we understand the Cold War in the 1950s and 1960s.

They're not just boring bureaucrats—but are they ever? I'm writing about the eighteenth century now, and realized I already made this same point about the twentieth century.

BORDEWICH: A stereotype persists today of Middle Eastern societies as particularly inclined toward conspiracy theories. You devote a chapter, however, to inverting common assumptions about conspiracy theorizing. Confounded by unrest in the 1920s, British imperial bureaucrats became obsessed with the notion that there was a single secret control center sowing global chaos. They believed this node of insurrection was in Iraq.

SATIA: The intensity of contemporary paranoid thinking in Middle Eastern states comes completely out of this colonial experience. It's part of the hangover of covert empire. The very discreetness of British rule in the region—through the air force and "advisory" bureaucrats and intelligence networks—made it impossible for people in the region to know when sovereignty was real and substantive, when they could be sure that a hidden agent of some kind was not pulling the strings of power from behind the scenes. Imperialism is crazy-making.

In the chapter on conspiracy theories, I emphasized how off-base the British were, how outlandishly exaggerated their theories were. But there were some real conspiracies, people forming secret connections. Some people did have a mystical outlook—and this was a challenge to colonialism. When I wrote Spies in Arabia, I was so sure that the British were so wrong in what they assumed about native inhabitants that I didn't pay enough attention to their actual interactions. This dimension comes out more in my current work on global anticolonial networks than it did in Spies. I'm now looking at the conspiracy theory chapter from the other side, in a sense.

BORDEWICH: You join other scholars practicing new imperial history in examining how domestic politics in Britain shaped and were shaped by the imperial experience in Arabia. What was the connection between mass democracy in Britain, the rise of the British Labour Party, and how the empire behaved in Arabia?

SATIA: At the moment of self-assertive mass democracy after World War One, new mechanisms of more discreet kinds of colonial control emerged—aerial control, intelligence networks with administrative power. State institutions evolved to continue to pursue certain imperial interests, despite the check that democratic expressions of opinion increasingly provided. The state was acting out of a paranoid understanding of the Middle East, and mass democracy channeled the anxieties of a society which, in the 1920s, was recovering from a horrible war and was paranoid about whether it could trust the state.

BORDEWICH: Air control plays a key role for you in understanding what happened to the British Empire as British people became more and more critical of it. Empire was no longer fashionable, so the empire moved to the air. It became invisible.

SATIA: Air control was cheaper than older ways of maintaining control, so it was less dependent on taxpayers approving it, and it required fewer personnel. This made it easier to hide from a mass democracy increasingly keen to assert its control over foreign policy after the disaster of the First World War. Air control was also less perceptible by Middle Eastern people. It was a very discreet version of empire in an increasingly anti-colonial time. At the same time, the British people knew just enough about it, and it was just enough shrouded in secrecy, that their imaginations could run wild—conspiracy theories imagining undercover British agents and oilmen behind every global news item flourished.

BORDEWICH: Most American readers probably come to this book thinking about American intervention in the Middle East, which escalated in the twilight of the story you're telling. You mention the first CIA interventions in Iraq in the '60s and include epigraphs from American officials like Paul Bremer who served recently in Iraq. Did writing this book change the way you thought about the nature or trajectory of the U.S. involvement in the Middle East?

SATIA: I was sitting in the Map Room of the British Library, researching this book, when 9/11 happened. As the American case for the war in Iraq was being prepared, the conversation revolved around intelligence and failures of intelligence—and about what we could and could not know. The prominence of aerial strategy in the Iraq War made me feel that the U.S. really had inherited the myth of the success of British air control. The echoes with my project were uncanny; it motivated me to finish the book as quickly as I could. I saw the gurus of American intelligence clearly influenced by the generation of the Spies in Arabia, the British Arabists. I wanted to call it out, but all I could convey was that there were resonances.

This made me reflect on how one can best be a historian and an active citizen in a democracy. What is the point of the critique you make? What kind of truth-telling can the craft do?

BORDEWICH: In writing about secrets, did you have to grapple with restricted access to sources?

SATIA: Sometimes there were things blacked out. But because of the way the bureaucracy works, if it's blacked out in the Foreign Office files, the copy that was sent to the Air Ministry is not blacked out.

This was such a formative moment in the professionalization of intelligence. Agents were making up the system of classification and bureaucratization. But I end my book just where access to sources would have gotten tough, in the 1930s. In the 1910s and 1920s, they didn't have the techniques for secrecy standardized.

BORDEWICH: Because you're trying to understand the epistemological framework of these agents, you also talk about the spy novel, the romance of which might attract people to reading the book in the first place. In doing so, you give a great example of how we can use literature to understand the history of institutions.

SATIA: It's so disappointing for people who buy the book because they love spy novels, and realize the book's so boring! But there is a close relationship between literature and the state actors I write about—it's no coincidence that the greatest living spy novelist from the British world is still John Le Carré, a former spy himself. Another way to get around the need to work with materials that might have been classified is that these spies were such prolific writers. Even if details were blacked out in official documents, they were blabbing in their letters, in their diaries, and in their minutes. They had a lot to say, and they said it in a literary tone. That's why they got into this business in the first place.

BORDEWICH: They were acting out the novel they wanted to star in.

SATIA: Spying is about fantasy and leading a double life, which is also what fiction is.

BORDEWICH: Your next book, Empire of Guns: The Violent Making of the Industrial Revolution, will be out in April. How did you get from spies in the twentieth century to guns in the eighteenth?

SATIA: Spies in Arabia had made me think about democracy, active citizenship, and state secrecy, and in doing so really affected what I thought I should be doing as a historian. E.P. Thompson's father, who was an army chaplain in Iraq in World War One and appears in Spies in Arabia, thought of the historian's craft as essentially about truth-telling. At this moment in our unending War on Terror, this is something historians should be doing more. We've abdicated our responsibility. We've let political scientists and economists and "security experts" talk about everything, and they don't know about anything's past. With this in mind, I wanted to do something that spanned a longer period, something that lots of people would want to read; I wanted to use my understanding of the inequities produced by colonialism to intervene in public debate.

I had a long, consistent interest in military technology. In addition to Spies in Arabia, I had written on wireless and radio, and on dams and rivers in Iraq. But what is missing from Spies in Arabia is a political-economic angle. I did a master's in economics at LSE, and my outside field for my oral exams was in economic history, with Barry Eichengreen and Brad DeLong at Berkeley. I felt political economy was missing from a lot of academic history on the British Empire, and arms trading was one way to bring these together.

As a historian of the twentieth century, I thought I would write on shifts in the arms trade during decolonization. But while I was looking for background on how the arms trade started, I stumbled on an article by Barbara Smith about the Galton family, who were Quaker gun-makers in Birmingham. That was all the information there was about them, though, and there was not much on the eighteenth-century arms trade at all.

I went to Birmingham to see the Galton family's papers there. In 1795, the Quaker church in Birmingham told them they should not be making guns, and Samuel Galton published a defense of his trade. He said he was publishing this defense for his children and for posterity, so that people would not judge him. This was a hand reaching out to me, saying "write about me." What he said made sense. He asked, "What would you have me do in industry that would not be related to war?" This was paradigm-shifting for me. What if he was right? Then the way we've been thinking about the Industrial Revolution is all wrong. So I completely switched gears and decided I needed to think about the Industrial Revolution.

BORDEWICH: Where does the story end now?

SATIA: The main story ends at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, but the last two chapters very quickly get us to the present. How did the arms trade proceed after that, especially guns, and how have people protested against the spread of small arms since then? It has such obvious connections with the American gun control debate and UN efforts to regulate small arms trading, which never seem to succeed. I try to make those connections explicit. The moment of controversy around Galton as a Quaker gunmaker echoes today. If his fellow Quakers saw him as merchant of death, his defense was to say that "all of you are bad," including the states that buy the guns. This was a formative moment setting the terms by which we judge, by which we exculpate some of us and hold others morally responsible for the spread of violence.

BORDEWICH: The way people grapple with the ethical dilemmas inherent in empire is obviously something that engages you. These Quakers are a clear example. But the British spies in Spies in Arabia also find themselves in morally complicated positions. As the empire is shrinking and changing form, as mass democracy is on the rise and empire becoming less palatable, how are the agents who are implicated in this project grappling with the ethical dilemmas inherent in their situation?

SATIA: So many of them love the Middle East, and Arabs, and there's a seeming contradiction in that: they become experts on this place because they love it, and then they destroy it. How do they live with that? How do they rationalize it? Do they even recognize what they are doing? From a human angle, that is fascinating.

I'm now interested in the global Left. I was drawn to it by my older interest in the Partition of India, and partitions everywhere. How do neighbors become enemies? How do the British abdicate responsibility and walk away, after professing to be responsible? It's the same set of questions over and over: Why do good people do bad things?

BORDEWICH: What are you working on now?

SATIA: I became a historian because I wanted to write a book on Partition. I shifted to British history, but it has stayed with me. I am currently interested in anti-colonial bonds across colonies in the modern period. What else besides India and Pakistan was possible? What federations, communist organizations, pan-Islamic organizations, and other ideas were people playing with?

I am looking at Indian Ocean connections, from India to East Africa. I'm also interested in Indians in California and their Ghadar Movement, which drew inspiration from the Irish. They were revolutionaries, global in their consciousness yet committed to going back to Punjab and liberating it. The imaginaries of these cosmopolitan anti-colonialists do not fit neatly into the nationalist narratives we tell about independence. The nation-state system was completely failing during World War II, yet it came back, and was again seen as the only way to organize the world. My project is a recovery of lost causes.

BORDEWICH: What are you reading at the moment?

SATIA: I'm teaching two classes right now, so I'm mostly reading what I've assigned my students: Lots of Orwell, Fanon, C.L.R. James, Cesaire, and Faiz Ahmed Faiz. I also have Ishiguro's new book halfway done on my bedside, which I interrupted to reread Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time in anticipation of seeing the new movie with my kids. Before that, I read and loved Mahmood Farooqui's A Requiem for Pakistan—the World of Intizar Husain.

BORDEWICH: You've published a number of op-eds in non-academic publications. Do you have any advice for our readers, many of whom are graduate students, for how to go about packaging their research for general audiences? How do you identify the right audience and then strike the right tone?

SATIA: I think as we research, we are often aware of the way in which our research question relates to current political debates. And writing those shorter pieces forces you to articulate that relationship explicitly and succinctly. It's not so much translating or repackaging your work for a general audience but learning a different genre of writing. And I think it has the really healthy impact of helping you see where you are being needlessly obfuscatory in your academic writing and thinking.

For an op-ed, you have to be quite clear on what you are arguing and why it matters. It's a win-win exercise in that you will help inform the public, and you will come away with more clarity about what you are doing and why it matters. There are so many media venues now that it's possible to share both the extremely timely aspects of your work when the news cycle demands it, and the more timeless aspects.

As I said earlier, I do think this is part of our duty as historians, especially since many of us receive public funding for our work. Our research is supposed to benefit the public.

BORDEWICH: Earlier in our conversation, you cited E.P. Thompson's father, Edward John Thompson, as a historian who envisioned the craft as one fundamentally about truth-telling. Are there historians working today whom you consider models in bridging rigorous scholarship with Thompson's vision?

SATIA: There are different kinds of truth-telling, so I see people doing this in different ways. I'll narrow it to my own field of modern Britain: My teacher Tom Laqueur always inspires me for the way he probes what you might call the existential truths of human existence—he does this with rigor but also poetic wonder. His writing exudes both those kinds of truth. Catherine Hall inspires me for the way she is continually discovering enormously important and yet strangely forgotten histories—of women, empire, national pasts. Emma Rothschild's way of writing about economic life is another kind of truth-telling, a kind of unmasking of historical reality and method. Caroline Elkins's work on decolonization in Kenya changed minds—and lives. Almost anyone trying to be helpful in the history-of-guns world is engaged in an endlessly exasperating effort at truth-telling.

As I'm answering this, I'm realizing that the work I most admire is defiant in its dogged empiricism rather than shrilly denunciatory—and work that is rigorously empirical but with a poetic quality too, and a kind of emotional intimacy...a hangover of the old idea that poetry offers a kind of transcendental truth—that feeling of existential relief when you read, say, Aimé Césaire's Discourse on Colonialism.