Queering the Pandemic

COVID-19 disrupted teaching and learning in universities across the world in the early months of 2020, forcing campuses to shut down and classes to move online. As we wrap up the first semesters of studying and teaching history in the midst of a global public health crisis, we can see that these circumstances presented unique opportunities to think critically about and contribute to histories of medicine and society. Eleanor Franklin and Aaron Wiegand, undergraduate students at Johns Hopkins University, created a digital humanities project that explores the unique impact of a global health crisis on the LGBTQ community. “The Queer and Trans Response to COVID-19” was developed for Dr. Elizabeth O’Brien’s History of Modern Medicine course. Editor-at-Large Kristie Flannery sat down with Eleanor and Aaron to discuss their project.

Queering the pandemic archive and website: https://transresponsetocov.wixsite.com/mysite

Eleanor Franklin is a sophomore at Johns Hopkins University majoring in Public Health Studies. She is interested in healthcare and housing access, particularly their relationships to identity.

Aaron Wiegand is a senior at Johns Hopkins University majoring in Biomedical Engineering. He is on the pre-med track and is interested in LGBTQ health and queer/trans history.

You collaborated to develop a digital archive that documents queer and trans responses to COVID-19. Can you tell us about what kind of primary sources you selected to include in the archive and why?

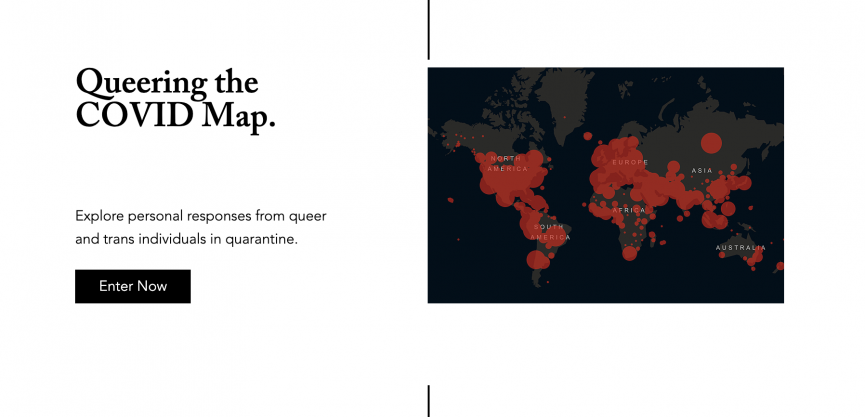

Eleanor Franklin: We chose primary sources from outlets such as Body Politic, Vice, and Vox, that reflected how the COVID-19 pandemic was impacting the queer and trans communities. As has almost always been true for LGBTQ issues, they are often not reported by mainstream media sources. To understand the impact of the pandemic on these marginalized groups, we dove into social media, grassroots LGBTQ news sites, and read between the lines of legislation. Thankfully, there were also great resources provided by groups like HRC, ACLU, and the UCLA Williams Institute. When looking for these sources, we placed emphasis on stories told by queer and trans folks rather than ones about them. This was also the main jumping off point for our own generated source, “Queering the COVID Map.” This map of personal responses would allow the community to speak directly for themselves, compiling direct voices that could be referenced for years to come.

Aaron Wiegand: Adding to this, a central question we kept in mind when choosing primary sources was: “who counts as a voice of authority?” Because we are in a pandemic, there has been a lot of deference to medical and public health experts as well as to medical institutions like our own university (Johns Hopkins). This deference sidelines the queer and trans people that have been advocating for themselves and their communities for years and that are struggling now more than ever because of the pandemic. This deference skews the public’s perception of the pandemic’s impact on marginalized communities by rendering its effects invisible unless “authoritative” sources choose to speak about it. Queer and trans people should be recognized as experts on their lived experiences and the issues affecting their communities and we therefore tried to bring as many individual voices into the archive as possible. Queer and trans people have known for years that doctors and medical experts are often woefully undereducated about LGBTQ health. Our lived experiences are incredibly valuable and deserve to be acknowledged as such.

You built this digital project for a history of medicine class. How did thinking historically about medicine shape your project on the COVID-19 pandemic as it was unraveling in real time?

Aaron: Dr. O’Brien’s “History of Modern Medicine” course emphasized the idea that our understandings of disease are, to a large extent, socially dependent. Knowing this, we felt confident that producing a body of work that emphasizes the lived experiences of queer and trans people during the pandemic would be incredibly valuable to our thinking about disease. Our Queering the Pandemic project works to decenter the medical and biological aspects of COVID-19. The commonly-accepted COVID-19 narrative is that those most at risk are people with underlying medical conditions, immunocompromised people, and the elderly. While biological factors such as immune function and age seem to be paramount for determining whether someone who contracts the virus will become critically ill or not, social factors are equally as important. Social factors can determine whether someone will have the means to avoid coming in contact with the virus or the means to survive the disease. The knowledge that historical and social context are vitally important when studying disease and medicine was at the top of my mind when conceptualizing our project. By centering queer and trans experiences of COVID and analyzing these in the context of LGBTQ history, our project gives a platform for future historians to understand the pandemic from the view-point of a group that has historically been forgotten and left at the margins of history.

Our Queering the pandemic project works to decenter the medical and biological aspects of COVID-19. The commonly-accepted COVID-19 narrative is that those most at risk are people with underlying medical conditions, immunocompromised people, and the elderly. While biological factors such as immune function and age seem to be paramount for determining whether someone who contracts the virus will become critically ill or not, social factors are equally as important. Social factors can determine whether someone will have the means to avoid coming in contact with the virus or the means to survive the disease…By centering queer and trans experiences of COVID and analyzing these in the context of LGBTQ history, our project gives a platform for future historians to understand the pandemic from the view-point of a group that has historically been forgotten and left at the margins of history.

Eleanor: Building off of Aaron’s point, our professors and TAs for the “History of Modern Medicine” emphasized the ways in which historical knowledge of disease is constructed by those who choose to document it as it occurs. All of the information that we have available to us about the history of disease and medicine was curated by historians who were fallible and human. Our understanding of history is limited by the voices that recorded it. One of our goals in creating this project was to ensure that the queer and trans response to COVID-19 and its lasting effects within the community would be included in the historical narrative years from now. If you want a story told, tell it yourself! We hope that queer and trans stories can continue to be amplified and integrated into the main fold of history and no longer simply subsections of a heteronormative recollection.

Your blog compares responses to COVID-19 to responses to the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s and 1990s. What were the most important lessons learned from thinking comparatively about current and past healthcare crises?

Eleanor: This was a topic that I saw referenced across multiple sources, and was also touched upon in my interview with Jonathan Santos-Ramos, the Director of Community Engagement and Strategic Initiatives at Callen-Lorde Community Health Center. There is an undeniable connection between the two, both in their similarities and in their differences. The mobilization time and the speed of the country’s response to COVID-19 was exponentially faster than the many years it took for Ronald Reagan to even say the word “AIDS.” However, both diseases take the highest toll on the same communities: low-income communities, communities of color, queer and trans communities, the homeless and marginally housed, sex workers, drug users, etc. In both cases, the disparate effects on these communities were and are not being addressed in the way that they should. There is a blindness to the inequity; it manifested in AIDS as a suppression of the entire pandemic, but with COVID-19 we are only paying attention to the groups we deem worthy of being healed.

Something that also stuck with me in the process of comparing the two health crises was a quote from the interview with Mr. Santos-Ramos where he explained that Callen-Lorde was prepared to take on the challenge of treating queer, trans, and homeless New Yorkers because the health center was “used to treating folks that no one else wants to touch.” Santos-Ramos described it as “muscle memory:” an instinctual knowledge within the community of how to care for one another, because they know that no one else is looking out for them.

Aaron: As Eleanor described, queer and trans people have been here before. This is not the first time that our community has faced a pandemic and fought governmental indifference and institutional inaction. Currently, I see a lot of people waking up to the reality of the U.S. government’s inability to address social issues in our country adequately. For many queer and trans people, these problems have always been obvious. AIDS is a disease of poverty. Living as an HIV-positive person is arguably a full-time job that is made harder when one’s country fails to provide adequate healthcare, infrastructure, and social services. Comparing the U.S. government’s response to the AIDS pandemic and its response to the current pandemic allows us to see how history operates in cycles. The virus has changed but the fact that it disproportionately hurts those in marginalized communities that are often forgotten remains constant.

History tells us that it is dangerous to place all our faith in biomedicine and our medical institutions. Medicine has failed to treat the social ills that are causing certain groups to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19.

History tells us that it is dangerous to place all our faith in biomedicine and our medical institutions. Medicine has failed to treat the social ills that are causing certain groups to be disproportionately affected by COVID-19. Similarly, medicine has failed to cure the current epidemic of violence against trans women of color. Medicine has failed to cure the many health disparities currently faced by queer and trans people. Acknowledging the history of AIDS in the present moment allows us to place queer and trans people as authorities in the current health crisis.