Review—Are port cities the keys that can unlock the history of globalization?

Darwin, John. 2021. Unlocking the World: Port Cities and Globalization in the Age of Steam, 1830-1930. Allen Lane.

Reviewed by Christopher Szabla, University of Hong Kong

For a book focused on processes of global interaction and integration, John Darwin’s Unlocking the World: Port Cities and Globalization in the Age of Steam, 1830-1930 had the unfortunate timing to appear not long after the world was thrown into the pandemonium of a global pandemic. Travel restrictions and supply chain problems compounded fears already bred by financial calamity and political reactions to the crises of globalization. Far from the “unlocked” long nineteenth century of intensifying trade and connectivity that consumes most of Darwin’s volume, the past years have seen much of the world on lockdown, with our eventual full return to the pre-pandemic status quo hardly guaranteed.

Yet Darwin’s history is not merely concerned with globalizing forces, but also their undoing. For one, as the author notes in a preface acknowledging the pandemic, disease was also a symptom of the coal-fired sinews stitched by steam-borne transit – with devastating effects on the port cities on which he focuses. But Darwin also evidences how port cities could serve as unlikely sources of the broader reckoning that was to come for his steam-sewn world after the early twentieth century, when borders, trade barriers, and geopolitical conflict undercut the political and economic sources of their livelihood.

While weaving this narrative, however, Unlocking the World can sometimes feel like two histories patched together. One concerns globalization writ large, focused on the innovation of steam, while the other focuses on port cities and how they navigated and channeled this world. The distinction recalls Braudel’s parsing of the surface waves of history, on the one hand, and its deeper currents, on the other. Their relationship in this volume, however, can feel uneasy. The book’s attempt to wrestle with the whole history of global interaction can be inventive, but embraces such a broad subject that it can be unclear how much is meant as an argument of its own or as background. Either way, this broader lens serves as a necessary connective tissue for some of the book’s other sections, which focus deeply on port cities. This necessity calls into question one of Darwin’s main theses: that ports, being the sites where “steam globalization” passed most intensely, were also the sites through which such globalization could, therefore, best be understood. “The port city in Asia, Africa, Australasia and the Americas was the entry point through which poured the money, manufactures, ideas and people, as well as the physical force, that flowed out from Europe,” he asserts, “and through which it extracted the ‘returns’ of tribute, raw materials, profits and rents…The port city was where all the varied agents of globalization encountered a local society. We can see there in close-up the pattern of acceptance or of adaptation and resistance to change; the terms on which inland regions were drawn into the port city’s web; and how far it was able to re-shape the culture and politics of its emerging hinterland.” To what extent does such a lens really provide a window on globalization as a whole?

Darwin’s previous books have surveyed the histories of world-spanning empires, making him well-practiced at painting a vast canvas. He often manages to merge sweeping, somewhat familiar arguments with genuine insights and details that fascinate specialist readers. In his first section on globalization, he works to define paradigms of global trade and interaction beginning as far back as the year 1000 (an origin point of globalization also recently propounded by Valerie Hansen), focusing on different forms of mobility as their “regulator” and “catalyst.” The entrepôt (inter-port) monsoon-wind trading world that passed goods forward via different clusters of local merchants and that existed before European expansion is one, the “Columbian” age of longer-distance sail the next. Yet the latter, he makes clear, was still meaningfully distinct from the world of steam.

The age of sail was shaped far more by the natural forces of wind and current, giving precedence to ports that fell well off the straight path of a crow’s flight. The relatively slow speed of interaction also meant that cultural influence did not necessarily flow in one direction over another. The need for Portuguese sailing vessels to call in Brazil on their return voyage from Goa and Macau, Darwin notes in one brief example, produced, for a time, a Bahia with “oriental” (Darwin here quotes an older account) tastes and habits, including “clapping hands at the doorway to announce arrival; sitting cross-legged on the floor; using the parasol as a sign of status; the seclusion of women; [and] the taste for mantillas and shawls.” Another seminal global history, Chris Bayly’s Birth of the Modern World, identified aesthetic uniformity as a key outcome of a later globalization. But Darwin’s illustration demonstrates how earlier forms of global interaction could spread style and culture in different ways and to surprising points on the Earth’s surface before steam.

Was the eclipse of the port city part of a broader evolution toward a more evenly distributed industrialization rather than an economy depending on Europe as a manufacturing hub – a process that may have begun even before import substitution, and that was itself a globalization made by steam?

Mechanization, by contrast, freed navigation from natural constraints. Over the course of the nineteenth century, horsepower rose by over ten times in many European societies (at least according to an 1892 “Dictionary of Statistics,” the use of which kind of source might be better couched in discussion of means of measurement and accuracy, but which, like other historical data used in Unlocking the World, is cited authoritatively.) Steamships carried higher volume trade and were inherently less risky investments than transport that depended on the winds and waves. They also permitted speedy, efficient routes carrying primarily European influences. “Heavy, dark European-style clothes and stove-pipe hats became de rigueur for the respectable classes – in the tropical heat,” Darwin writes. This was the world in which Joseph Conrad could write of such incongruously-dressed figures lingering at the oceanic terminus of the Congo River steamboat, and one in which the ‘Great Divergence’ described by Kenneth Pomeranz made European domination palpable in Asia. Steam also brought settlers to distant shores in greater numbers and helped grow other networks spreading European influence, from telegraphy to finance.

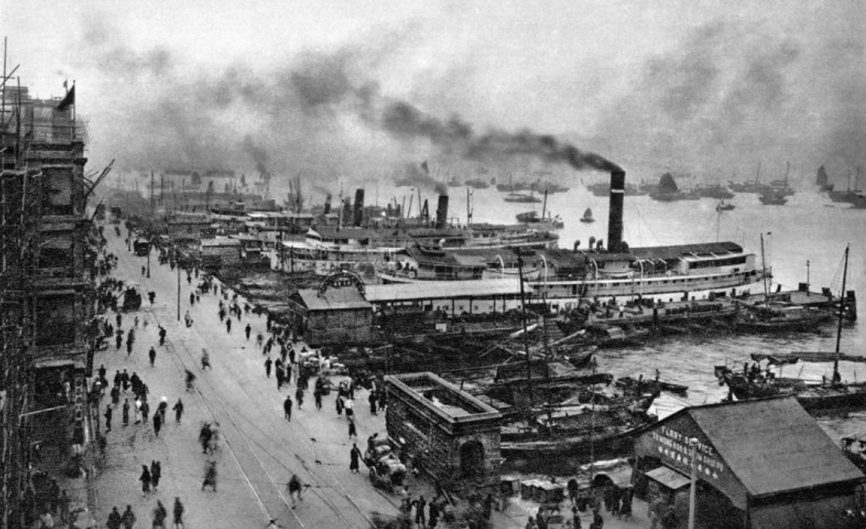

Despite this overall Eurocentricity, steam globalization shifted balances of power in other ways. It impacted the hierarchy of port cities everywhere, combining with other historical forces to hand primacy from harbors such as Malacca (which “owed its fortune to the winds: it was where ‘two monsoons met’”) to Singapore (which lay closer to straight-arrow shipping lanes that passed from the Indian to the Pacific Oceans than other competing ports.) The mass trans-Pacific voyages of Chinese emigrants that large steamships enabled helped make Hong Kong the world’s seventh largest port by tonnage by 1935, and their remittances contributed to its rise as a financial center. Interoceanic canals, now approachable via routes such as the Red Sea that would have been unfavorable in the age of sail, empowered ports such as Marseille, Trieste, and Bombay (beneficiaries of the Suez route), reinforced the position of others (such as Aden, a meeting point of winds that became relevant again as a Suez stop), and threatened to cast those that lay off-piste, like Valparaíso, into relative decline. Oceangoing steam was not the only technology that made port cities: their ability to forge riverine and railroad links to the interior was critical for their competitiveness. Before steam, even Paris was difficult to reach against the difficult northward-flowing currents of the Seine.

For Darwin, connections forged at the interface of ocean-facing harbor and hinterland-conquering transport made the successful port city, and helped it function as this era’s “hinge.” Such cities imported “modernity” from Europe and collected other cultural influences from abroad. A consequence of steam globalization was therefore that the port city became both an alien presence to the masses in the interior and a dynamic place that attracted them. Flowing into these hubs, they witnessed not only the preferential treatment given to European mercantile elites, but to local compradors who often hailed from minority communities, from the Zoroastrian Parsis of Bombay to the overseas Chinese of Southeast Asia. They experienced mass inequality in comparison to these classes just as new ideologies of national and spiritual liberation lit sparks in the hinterlands that could have momentous consequences for the prosperity of port city life. As peripheral port cities exported en masse to European hubs, however, there was also an increasing reversal of influence in the steam world (as Darwin suggests in a somewhat abbreviated segment): the coastal cities of Europe that received peripheral port cities’ wares came to resemble them in their competitiveness, their ability to provoke nationalist reaction, and their revolutionary potential. “It is easy to imagine that steam globalization was something exported from Europe to the rest of the world,” he writes; “yet, of all the continents in 1914, Europe had been the most intensely globalized.”

These threads, brought together, invite questions about how much of Darwin’s narrative is properly understood as global history as opposed to a history of European expansion – and to what extent it is possible to separate the two in this era. Surprisingly for an imperial historian, only well into the volume does Darwin truly begin to explain how globalization and different forms of empire interact in his account. Perhaps focusing on the port city sometimes obscures how empire mediated globalization’s impact. The case studies on which a large part of the volume (for not entirely clear reasons) focuses – New York, New Orleans, Montréal, Bombay, Calcutta, Singapore, Shanghai, and Hong Kong – shared commonalities in, among other things, their mercantile wealth and cosmopolitan connections to the broader world, and the unstable inequality and resentment they could engender in the hinterlands on which they also depended. Yet the cultural dynamics of North American metropoles were distinct in that their hinterlands were vastly remade by imports of European settlers, who were not quite as culturally far removed from, and thus less inclined to challenge, those metropoles’ “foreign” characters, which largely arose from their ongoing connections to Europe. In both India and China, by contrast, alien merchant communities bred contempt of foreign hegemony in the ports and, eventually, political movements that fed off both this resentment and port city inequality and, eventually, undid much of those urban centers’ status by evolving into postcolonial governments that were unsympathetic to commercial elites and global connections. Midwestern suspicion of an alien New York would never have the same effect as a communist insurgency on capitalist Shanghai or a closed national economy on colonial Calcutta. (More detail on Latin America may have helped show how informally colonized societies diverged from these examples, or if semi-settler societies thought of their port cities in ways distinct from those in North America or Asia.)

Given that distinctions between hinterlands distinguished settler colonial and colonial ports above all, the volume would have also benefitted from deeper discussion of non-urban spaces. In some cases, the book allows hinterlands to appear shaped by ports in ways that one might question. Montréal, Darwin shows, had to use railways and its influence over national policy to integrate the Canadian market after New York undermined Montreal’s aspiration to be chief port for the continent. But could this focus on one city perhaps overstate the role Montréal played in making Canada? (Interestingly, Darwin does not attribute the city’s commercial downfall to Québecois nationalism – as many do and which would have provided a parallel with Asian ports – but to its elites’ British ties, which waned in importance compared to Toronto’s American ones by 1945.) The book could say more still about the hinterlands of Asia, given how Darwin effectively argues that its ports’ fate depended to an even greater extent on developments in them. The Christianity that sparked the Taiping Rebellion – and kicked off a century of westernizing reform efforts in China – may have been introduced via treaty ports, but to understand its popularity perhaps requires demonstrating how it spread among ripe conditions of alienated impoverishment in rural Guangxi (as Stephen Platt details in Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom.) Darwin is cogent about needing to correct a “landward bias” in Indian history by focusing on ports, but he may still have acknowledged how the growth of Gandhian ideology was not just a rejection of port city urbanity, but a religiously-tinged nationalism that spoke directly to rural India (as does subalternist Shahid Amin in his Gandhi as Mahatma.) The Chinese Communist Party may have been born in Shanghai, but the Maoist maxim of “surround the cities from the countryside” – which, as Julia Lovell’s Maoism: A Global History reminds us, took root around the world – required specific rural conditions to develop and succeed. A still more radical challenge arises from Andrew Liu’s recent Tea War, which shows forms of innovative capitalism developed on locally operated Indian and Chinese plantations using methods independent of those imported from Europe. This calls into question the extent to which European tools and ideas imported through coastal cities were actually the engines of modernity. Some complex interactions between port cities and hinterlands also go underexplored. One fascinating argument Darwin suggests is that in acting as an anomalously distant center for Chinese nationalism where elites were able to curtail its effects (yet being too alien to nearby Malaya to be subsumed by it), Singapore nearly alone in Asia escaped the fates of the continent’s other ports. Yet this exception raises questions about how and when imagined hinterland communities could matter more than actual ones.

There is also arguably missed potential in focusing too much on shipping and transport, specifically; Darwin frequently notes transformations from maritime to industrial center in passing, including an early move to protectionism in North America and Indian and Chinese ports’ development of significant manufacturing capacity under colonial rule. Shanghai, he suggests, was able to thrive well into an era of violent chaos in interwar China on the strength of a previously developed, self-contained industrial economy. Was the eclipse of the port city part of a broader evolution toward a more evenly distributed industrialization rather than an economy depending on Europe as a manufacturing hub – a process that may have begun even before import substitution, and that was itself a globalization made by steam? Was it a process, moreover, that is perhaps difficult to discern amid a focus on oceanic connections?

Incorporating so much more about rural regions and industrialization into a volume already attempting to address both the histories of globalization and port cities may have made Unlocking the World impossible to publish – it is lengthy as it is, if a little padded by expository description (we are told, twice, about London’s ancient advantage as the lowest place where one could bridge the Thames). It may have also been difficult to maintain any unique focus on ports while paying sufficient attention to all the independent causalities that arose in the global countryside or broader economy. Yet the significance of rural and industrial developments suggests that a comprehensive global history – especially a global history that is as serious about chronicling reaction to globalization as it is to its growth – may not be able to be written through or focusing in too much detail on port cities alone. If they were the “hinges” of the era, it may be important to remember that doors usually open and close by motions initiated on their handles.

Ultimately Darwin is aware of the limits of port cities as lenses onto the broader history of globalization. If he does not account for the entire globalizing world in detail, he acknowledges what can be left out of such accounts altogether: “all round the rim of the ‘globalized’ world still lay a vast periphery of shifting cultivators, land-hungry peasants, impoverished reservoirs of migrant labour and the battered remains of displaced indigenous peoples.” Steam globalization’s undoing was also, he writes, a product of forces beyond ports. Steam facilitated the imperial competition that undermined the Pax Britannica on which seaborne fin-de-siècle globalization rested (the ability to “lock up the world” that is the foil for Darwin’s title was originally a phrase coined by a British naval theorist, in the face of geopolitical rivalry.) Such competitiveness, in turn, undermined free trade and ultimately led to world war – the consequences of which were economic devastation and more protectionism. Steam age technology also helped build resistance to empire. Nationalist movements and the nation-state could use the transportation and communication tools of the era to grow and to integrate territory in ways distinct from the port city’s colonization of its hinterlands. Eventually, these forces were able to subsume the globalized port itself.

Port cities still played roles, but often tangential ones, in these processes. Darwin notes how Hamburg-Amerika steamship company director Albert Ballin concluded that Imperial Germany needed a more powerful navy to guard its growing commerce. Yet while successful ports of earlier eras had secured state protection, other influences – Darwin here hints at Germany’s agrarian elite – appear by this point to have been in the driver’s seat of a larger trend toward securitization. His coda focuses on Smyrna, a classic case of a cosmopolitan entrepôt wiped away by a vengeful interwar nationalism. Smyrna owed its diversity and prosperity to the protection of imperial powers which had imposed capitulations on the Ottoman Empire, but has become known for the consequent destruction of its once-leading Greek merchant community by the newly-established Republic of Turkey. Deeper into the twentieth century, once “infidel Izmir” had become a “modest” manufacturing city “sheltered by tariffs.” Smyrna’s history can illustrate how broader forces propelled and undermined it, but perhaps not entirely how those forces arose. Not all of the ingredients that unmade cosmopolitan port cities necessarily filtered first through their own docks. The wider histories of the First World War, European colonial designs, the organization of the Turkish Republic in the Anatolian interior, intellectual currents in favor of a stronger state and economic protection: all can feel removed and abstracted in relation to Smyrna – until they come crashing down on it.

Steam facilitated the imperial competition that undermined the Pax Britannica on which seaborne fin-de-siècle globalization rested (the ability to “lock up the world” that is the foil for Darwin’s title was originally a phrase coined by a British naval theorist, in the face of geopolitical rivalry.) Such competitiveness, in turn, undermined free trade and ultimately led to world war – the consequences of which were economic devastation and more protectionism. Steam age technology also helped build resistance to empire. Nationalist movements and the nation-state could use the transportation and communication tools of the era to grow and to integrate territory in ways distinct from the port city’s colonization of its hinterlands. Eventually, these forces were able to subsume the globalized port itself.

As such, while port cities may illustrate many forces of globalization, using them as the central lens may risk simulating the effect of blinders: not unlike what transpired among these cities’ merchant elites, who were sometimes too concerned with raising funds to dredge their harbors and compete with ports down the coast to pay close attention to greater lurking threats. Still, a global history of port cities is valuable in and of itself. Although Darwin asserts that what makes for a “global city” today is not necessarily what made a successful port during the age of steam, the distinction he draws is that today’s globalization appears to favor Asia as much as the earlier variety did Europe. In terms of attributes of cities themselves, his narrative may still hold lessons that could be applied to cosmopolitan hubs from rising Gulf emirates (that will no doubt face their own challenges and crossroads) to precarious Hong Kong, which Darwin sees as a Singapore-like exception to the end of the age of globalized steam ports, albeit a more “embattled” one.

These lessons do not necessarily cut in directions that favor existing political divisions. Darwin writes that the most successful ports were entrepôts with perspectives that embraced the world more than their immediate neighborhood. He quotes one observer of steam-era colonial Hong Kong that it “was a sort of cosmopolitan Clapham Junction, where passengers change and goods are transhipped for everywhere.” Inland rulers, he also suggests, needed to facilitate the interests of mercantile elites and cosmopolitan networks, rather than capture or curtail them. At the same time, local elites often needed to call on distant sovereigns to crush rebellions resulting from ports’ gross inequalities or cultural tensions, and to ensure their economic links to the nearby hinterland, which could supplement entrepôt status. Of course, these lessons – and their focus on the fortunes of patrician merchants – raise questions about what Darwin means by the “success” of the globalized port city (among those that lost out, he notes, were Boston and Sydney) and to what extent democracy was compatible with it, either in the age of formal empires or today.

Nevertheless, both these lessons and the questions derived from them will probably continue to be significant in the world after COVID. As Darwin notes, some of the questions of steam globalization – such as if, how, and when the economic influence of China’s port cities could completely transform its interior – remain open ones. The expected slowdown in global trade has been perhaps more limited than expected so far, with supply chain snarls more a product of intensified demand rather than its decline, and reshoring those chains themselves more difficult to achieve than earlier forecasts avowed. Whether a globalized world will revive, enjoy what Darwin calls a brief “false dawn” like that of the 1920s while the ground continues to shift, or is facing a moment akin to the Depression, in which the persistence of the disease gives rise to longer-term shifts in socioeconomic structures, port cities (or today’s air hubs and “global cities” in general) will continue to be a lens that can demonstrate many of globalization’s forces, tensions, and contradictions – if not, perhaps, the whole story.