Review—Race Women Internationalists: Activist-Intellectuals and Global Freedom Struggles

Imaobong D. Umoren, Race Women Internationalists: Activist-Intellectuals and Global Freedom Struggles (University of California Press, 2018).

Reviewed by Zaib un Nisa Aziz, Yale University

It has been over thirty years since the publication of Anna Davin’s classic article on ‘Imperialism and Motherhood’. Like so many in her generation, Davin was both a feminist and a historian. She was hence committed both to the political project of women’s liberation and a scholarly project of writing women’s histories; and indeed, saw the two as mutually constitutive. The years around 1978, when the article first came out, were particularly generative for women’s studies. While many of her colleagues, justifiably, brought the lens of gender to issues of class, labour, and sexuality, Davin’s contribution was unique in its geographical scope and analysis. By illustrating the relationship between the domestic discourse on maternity and population growth to the concerns surrounding the racial health and progress of the British empire, Davin made the crucial analytic gesture of globalizing the domestic history of women by putting it in conversation with the history of colonialism. Today, that concern is at the heart of the field of women’s history – and happily Davin’s article is still being read.

The notable rise of imperial history on the one hand and global paradigms on the other have had a lucrative impact on women’s history. The history of twentieth-century revolutionary activism has particularly benefitted from the transnational turn. A rich and growing body of work charts the various trajectories of revolutionary characters from the colonial and postcolonial world. Yet the quintessential figure of the peripatetic revolutionary in exile remains, for the most part, male. This owes in part to the historical fact that male mobility during the time was simply greater – men could move with relatively more ease and incur fewer social costs should they decide to stay away for longer. But the imaginative hold of this figure is partly to do with the privileging of that experience in historiography. It is thus vital to show that women, especially non-European women, also participated in the political and social discourse that shaped the twentieth century.

Imaobong D. Umoren contributes to this scholarly agenda in her recent book, Race Women Internationalists: Activist-Intellectuals and Global Freedom Struggles. Umoren’s international history features three main protagonists – Jamaican poet Una Marson, Martiniquan writer and journalist Paulette Nardal, and American civil rights activist and anthropologist Eslanda Robeson. Building on works by Marc Matera and Jennifer Boitten among others, Umoren tells a story about the “black diasporic networks and organizations in the United States, Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean that emerged in the wake of large-scale black migration from the late nineteenth century.” She takes us through the overlapping of world of her characters to showcase the involvement of Black women in the movements and conversations that defined twentieth-century international politics. Umoren coins the term “race woman internationalist” to indicate those Black women who “were public figures (and) who helped to solve racial, gendered and other forms of inequality facing black people across the African diaspora.” These women, like many others of their generation, owed their mobility to common historical phenomena and were embedded in common networks. Their lives sometimes intersected, and they populated common physical and imaginative geographies.

We gain three methodological insights from Umoren’s transnational approach. First, by focusing on the lives and journeys of her characters, Umoren showcases the importance of friendships, familial relations, sociability, and conversations in the politics of activism. Una Marson’s membership at the British Commonwealth League (BCL) in the early 1930s led her to befriend a number of activists including the feminist novelist and campaigner Winifred Holtby who became her “close friend and mentor.” Nardal’s decision to defy the Vichy regime led her closer to radical resistors and writers such as Aimé and Suzanne Césaire. Robeson, who had the most international career amongst the three, fostered political affinity with her counterparts across Asia and Africa. Her friendship with the ANC leader Alfred Xuma in South Africa played a role in her internationalist outlook—for example, conversations with her friends led her to draw comparisons between the apartheid regime and Jim Crow South.

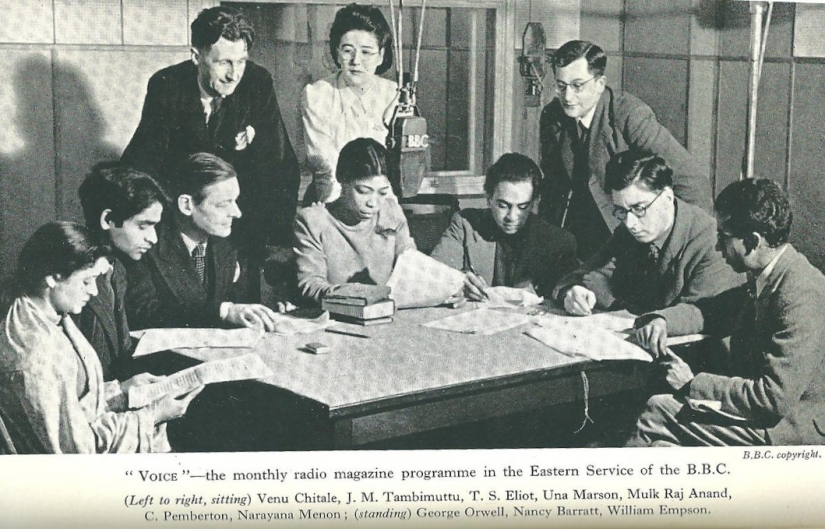

Secondly, Umoren highlights how the world of race-women internationalists was a world of letters. While the book cannot be regarded as an intellectual history since, as it does not engage rigorously with the work of any of these women, it does signpost the contributions Black women made to the transnational public sphere through their writings. Nardal was a journalist who began her career by writing in liberal magazines like the Le Soir colonial and La Dépêche Africaine and continued to write for newspapers and magazines on questions of gender and culture. Marson was a playwright and the first Black woman to employed by the BBC during the Second World War. Robenson extensively wrote for left-wing newspapers and periodicals on either side of the Atlantic and reported for the Associated Negro Press.

By juxtaposing the lives and letters of these women, Umoren is able to illustrate not just their commonalities but more importantly their differences. This is the third, and in my opinion, the most significant part of this work. The category of “race women internationalist” does not mean to imply a unity of politics. The lives of these women sometimes overlapped, and they populated common geographies. But their politics was very diverse and bore no affinity to a single ideological cause. At times, their travels resulted in their politicization as was the case with Robeson who became involved with radical Black activists. Nardal was a political conservative and championed many middle-class bourgeoise values throughout her life. And Marson, while participating in progressive politics in her early years in Kingston and London, eventually became quite reactionary in her politics. The book tasks the reader to think about this diverse and complicated set of lives. By focusing on women who did not hold a strict ideological or political affinity, Umoren seeks to show “the breadth of race women internationalists.” But equally importantly, this approach showcases the diversity within Black radicalism as a whole. While many scholars rightly pay attention to traditions of Black radicalism, Umoren shows that liberal and conservative voices also cohabitated in these transnational circles. Women like Marson and Nadal, who were not radicals, occupied the same circles as W.E.B. Dubois, George Padmore, and Jomo Kenyatta.

Hence, a difference of politics did not preclude other types of connection. Indeed, these people were bound up in various types of relations. And such relations could and did lead to broad-based movements that cut across different ideologies. This is precisely what happened during the anti-fascist campaign against the 1935 Italian occupation of Ethiopia. That moment witnessed the mobilization of a vast number of Black diasporas in solidarity with Ethiopia. Though ideologically diverse, Nardal, Marson, and Robenson all work in different capacities under the common umbrella of international anti-fascism.

The excavation of stories of Black female figures is an important end in and of itself. But given the diversity of their politics and their commitments, should these women be classified into one category? Umoren shows that the analytic yield of this categorization lies in accounting for the diversity and complexity within Black feminist and internationalist politics. An important part of the scholarly project of women’s international history is to show women and especially of women of color not only as mobile actors but as intellectuals and thinkers. Umoren’s book has brought us a little closer to the realization of this objective.