Review—Made in Britain: Nation and Emigration in Nineteenth-Century America

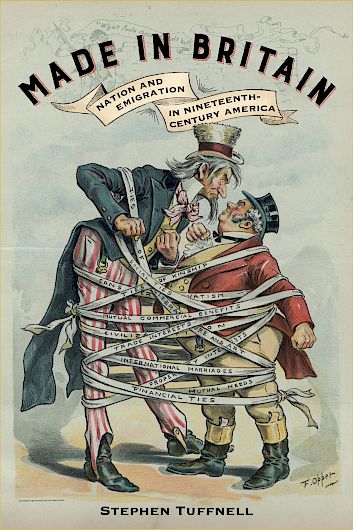

Tuffnell, Stephen. 2020. Made in Britain: Nation and Emigration in Nineteenth-Century America. Oakland: University of California Press.

Reviewed by Henry Jacob, University of Cambridge

In a 2006 interview, Sven Beckert lamented that in his field, nineteenth century United States history, “we still have a real dearth of studies that explore core themes in US history from a transnational perspective.” Fourteen years later, Stephen Tuffnell’s Made in Britain is among the latest in the growing body of scholarship dedicated to filling this lacuna. Contrary to popular opinion, Tuffnell posits that the US should be seen not only as a nation of immigration, but also of emigration. Indeed, American emigrants to Britain occupied a vital place in the US imagination during the nineteenth century; in constructing versions of themselves in relation to their former colonial rulers, they produced a novel vision of America and its position in the world. For Tuffnell, denationalized Americans exerted a key role in this period because they confused traditional boundaries of belonging. Living in England, but still maintaining bonds to their homeland, these figures engendered transnational networks of power and knowledge. Whether establishing new businesses in London, shipping goods from Liverpool, or frequenting diplomatic circles, these travelers provided inroads for their country of birth to reach a global stage.

Crucial to Tuffnell’s thesis lies a sophisticated explanation of how the US evolved from revolutionary independence to sociocultural interdependence with the UK. Surveying from the 1790s to the start of the twentieth century, Tuffnell scrutinizes “the transnational spaces organized and occupied by American emigrants… [as well as] the dense web of social connections they forged with one another and with their British hosts.” Throughout these five engaging chapters, Tuffnell recounts the lives of Americans from a variety of social, political, and commercial backgrounds. This toggling between microhistorical cases and macro-scale reflections advance the book’s aims well. Striking a balance between details about quotidian habits and consequential events like the Civil War elucidates the undetermined nature of US notions of self. In inspecting these levels of cultural encounter, Tuffnell cogently demonstrates that “American emigrants became the necessary counterpart of American nation-building and identity formation, and integral to its foreign relations.” This dual, and at times tense, desire for political autonomy and socioeconomic integration shaped expatriates’ dealings with Britons.

By electing mobility as an object of inquiry, Tuffnell indicates the fluid ways in which Americans understood themselves through others. This method poses further intriguing questions on how to analyze polities through “representative individuals” not rooted to their homeland. For example, Chapter 4, “Empire, Philanthropy, Public Diplomacy,” delves into how Americans employed competing discourses of freedom and imperialism during the 1860s. Though situated on opposite ideological poles, Northerners and Southerners alike could find themselves within the British empire. In appealing for aid, Union supporters pointed to Britain’s self-regard as a benevolent, abolitionist empire. Confederates, on the other hand, noted the disjuncture between the metropole’s liberal rhetoric its grip over far-flung colonies. In addition, African Americans such as William Howard Day advocated that runaway slaves resettle in West Africa, an approach resonant with British emigration policies. As this case suggests, expatriates formulated beliefs according to their own, and often conflicting, interpretations of empire and liberty. Interestingly, this instance also implies the malleability, as well as the versatility, of a national character. Tuffnell does well to incorporate these accounts to underscore the heterogeneity of US citizens’ experiences abroad. As Made in Britain evinces, the evolution of collective identity is not an internal, but instead an interactive process that requires a parallel historical treatment.

Thus, Tuffnell invites further creative approaches to understand America through the global channels its citizens inhabited. Focusing on these transnational flows also advances beyond a narrow, nation-based historiography. In this sense, then, Made in Britain stands as a welcome contribution to the burgeoning literature evaluating the US from beyond its borders. Given this work’s methodology, it fits in nicely with Kristin L. Hoganson and Jay Sexton’s (eds.) Crossing Empires: Taking U.S. History into Transimperial Terrain, another recent endeavor to broaden the scope of American studies.

On this point, future work can augment Made in Britain by focusing more on the voices of women and nonwhite Americans who occupied these transatlantic spaces. Given Tuffnell’s stated scope of elite émigrés, it is perhaps unsurprising that figures such as Ida B. Wells only make cameo appearances. Further attention to these more marginalized actors would extend Tuffnell’s interpretation of these “representative” Americans. Authors that place these perspectives in dialogue will add a comparative nuance to Tuffnell’s remarkable effort. Without doubt, this minor critique does not diminish the originality and value of this contribution. It is to Tuffnell’s credit that he has opened possibilities for more ripe areas of research.

In addition to complementing recent scholarship, Made in Britain benefits from its wealth of pictorial content and numerical data, offering excellent descriptions of these materials. In addition, Tuffnell buttresses his writing with an impressive amount of archival research at smaller and larger institutions. Accessible to non-specialists yet appealing to an academic audience, this text could prove suitable for coffee shops or classrooms.

Finally, and when viewed in conversation with his earlier publications, Made in Britain seems a natural progression of Tuffnell’s recurring interest in America’s station over the nineteenth century. Having previously investigated topics such as the migrations of engineers and gold rushes, this transatlantic approach furthers Tuffnell’s ongoing effort to open nineteenth century US history to the globe.