The 1970s in Arab-American Perspective: An Interview with Salim Yaqub

In recent months, a young and charismatic Arab-American doctor running for governor of Michigan has stirred up US politics. The son of Arab immigrants in the United States, Abdul El-Sayed is part of the latest generation of Arab-Americans. El-Sayed and people like him suggest a significant sociological transformation taking place within the Arab-American community. Their political activism can be seen as a generational leap beyond the activism of their fathers and grandfathers.

Studying the contemporary dynamics of Arab-American relationships gives some clues as to the transformation of objectives over time. Prior to the 1970s, the main concern for Arab-Americans was cultural integration. Then, from the 1970s, internal policies such as immigration reforms in the US created opportunities for these two societies to get to know one another more closely. Fluctuations in America's foreign policy in the Middle East–sometimes referring to the Middle East as one of its fiercest enemies, sometimes as its loyal ally–have also had a considerable effect on perceptions of Arab and American societies toward one another. Nowadays, a new generation of Arab-Americans is playing a pivotal role in debunking certain biases and rhetoric about Arabs.

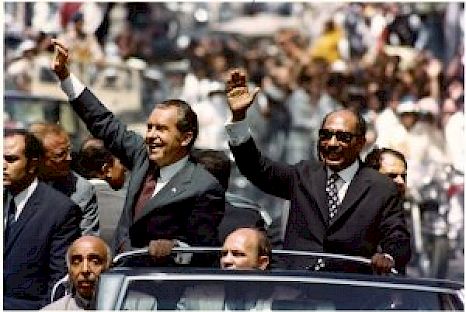

Our most recent guest, Salim Yaqub, is Professor of History at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His most recent book, Imperfect Strangers: Americans, Arabs, and U.S.–Middle East Relations in the 1970s (Cornell University Press, 2016), examines social and political dimensions of the Arab-US relationship during the 1970s, allowing us to understand the perceptions of two groups toward each other. It also sheds light on how the position of Arab-Americans changed according to the developing political situation in the 1970s focusing, for example, on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. The book stresses the need for a global perspective in understanding the roots of contemporary debates on U.S-Middle East politics.

—Fatma Aladağ (Istanbul Şehir University)

INTERVIEWER

Where were you born and raised? Where did you do your undergraduate work?

SALIM YAQUB

I am American-born although my father is Palestinian. He came to the United States in 1950 to study at a university and there he met my mother who was an American. They got married in the US and, when I was three years old, my family travelled back to the Middle East. We lived in Beirut, Lebanon for many years. Even though I was born in the US I spent most of my childhood and teenage years living in Beirut. At that point, in 1981, I returned to the US. Initially I did not study in an academic program. Rather, I went to art school and did my Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in illustration. I spent the next several years, much of the second half of the 1980s, working as a freelance illustrator in the San Francisco area. I did not have an academic background but after several years of working as an artist, I decided to go back to school to study something more academic. At that point, I started studying history and was eventually able to enter a PhD program.

INTERVIEWER

When did your interest in global history start? Was it academic or more personal?

YAQUB

I would say that it was more personal. As I said, I grew up living in Lebanon. The years I was in Lebanon were between 1966 and 1981. So that was obviously a very troubled period when there were lots of conflicts between Israel and the Arab states and also the Lebanese civil war in the mid-1970s. Even though I was not personally very interested in international politics, I gained a perspective on global affairs and acquired a close familiarity with the politics of Arab nationalism, Palestinian issues, and the Arab-Israeli conflict and so forth. So, these were subjects that I did not know very much about in terms of detailed academic study but they were subjects that surrounded me all the time. I gained a strong sense of how people in the region felt about these issues.

INTERVIEWER

What motivated you to write Imperfect Strangers?

YAQUB

My first book was about U.S-Arab relations in the 1950s and it came out in 2004. As I was completing that book I was thinking what my next project should be. I wanted to write about something that I personally remembered. The first book was about the 1950s, the period preceding my birth. I thought that if I wrote about a later period that I actually remember that would be more interesting. As I said, I lived in Lebanon throughout the 1970s; I had a strong interest in the US-Arab relations of that time period. Also, as I was thinking about my next project in the early 2000s, a lot of documentary material–that is, government documents that had previously been secret–were being declassified and made available to the public. These documents were generally related to events from thirty to thirty-five years prior. It seems like a great opportunity to write a fresh history looking at the documents that had not been previously available to scholars of US-Arab relations in the 1970s.

INTERVIEWER

What kinds of archives and sources did you use, and in what languages? How did you find the archival experience for this book? Did it differ from your previous book?

YAQUB

Great questions! A lot of my research was in government documents. The main collection of governments was US documents that were housed either in the National Archive in Washington, D.C. or in various presidential libraries associated with the presidents who served in the 1970s, such as Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and a little bit of research in the Ronald Reagan libraries. Those really were the main places where I got official documents that were declassified. In addition to that, I also went to London to look at British government documents at the British national archives. There really was not an opportunity for me to look at Arab government documents. So, I relied instead on some Arabic newspapers and Arabic language memoirs to acquire some perspective from the Arab side. One difference between this project and my previous one was that for my first project on the 1950s, I did actually manage to do some archival research in Cairo. I was able to look at some Egyptian Foreign Ministry records. However, those materials were not really available for the 1970s in Egypt. Also, in the midst of my project, the Arab Spring began and the situation in Cairo and other parts of Arab World became more difficult. Hence, it did not seem feasible for me to try to arrange archival research in the Arab world. The other kind of research that I did was looking at the papers, letters, and documents of Arab-American organizations and Arab-American individuals in various libraries.

INTERVIEWER

Why did you choose to focus on the 1970s in analyzing Arab-US relations?

YAQUB

In addition to the reasons I mentioned, I wanted to participate in a broader discussion taking place within the historical profession about the meaning of the 1970s. For several decades after the 1970s, historians tended to dismiss that era as being rather uninteresting. When compared with the radical upheavals of the 1960s and the conservative restorations of the 1980s, the 1970s seems to be a rather bland and formless interlude between those two periods. However, by the early 2000s, historians were looking anew at that decade and were starting to appreciate how crucial that period had been on a whole number of levels in terms of understanding what kinds of transformations took place globally and in the global economy. Also, the 1970s seemed very important for US history. Basically, people were arguing that to understand the world we live in today you need to look closely at the 1970s. I thought that this insight applied to US-Arab relations as well. Hence, I make an argument about how patterns established and opportunities missed in the 1970s help us understand the nature of the US-Arab relationship today.

INTERVIEWER

Where do you locate your book within other studies on the Arab-US relationship? What sets your work apart from theirs?

YAQUB

At the very basic level it is really the first or at least one of the first books that look at the overall US-Arab relationship in various dimensions in the 1970s. It looks at diplomacy, political relations, cultural perceptions between Arabs and Americans. And it looks at domestic debates within the United States about US-Middle East policy and at the emergence of Arab-Americans as an important political group. What distinguishes my book from previous ones is the comprehensive nature of the study and the fact that I am looking not at one small part of the 1970s on the one hand, and not at several decades on the other. Hence, what distinguishes of my book that it is looking at the whole decade and only at that decade.

There are also some arguments I make about the nature of US foreign policy that go against the grain of other studies. For example, I look closely at the Middle East policies of Henry Kissinger who was Secretary of State for several years in the 1970s, and I argue that he pursued a set of policies and series of negotiations that were very consequential in terms of the later unfolding of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Essentially what Kissinger did was to shield Israel from international pressure to withdraw from the territories it had acquired in the 1967 Arab-Israel War. I argue that this was very deliberate on Kissinger's part. He set out to create a scenario in which Israel would be able to hold on to substantial portions of the occupied territories. He deliberately designed policies and negotiated strategies to achieve this result. Previous historians, of course, had known that the end result of Kissinger's foreign policy was Israel's continued occupation of the land acquired in 1967, but until I wrote my book historians tended not to see that as deliberate. I argue that this is something Kissinger deliberately did.

Another way in which my interpretation differs from the interpretation of other scholars concerns the politics of Arab-American activism. A number of scholars who look at Arab-American activism argue that this was a time when a process of de-assimilation occurred. After several decades in which Arab-Americas were becoming increasingly assimilated into American society, Arab-Americans began feeling less and less that they belonged to the United States and more and more like foreigners in this country. What I argue is that yes there is an element of truth to that argument but it misses some other dimensions, some other ways in which Arab-Americans were actually becoming more assimilated into American society in terms of their ability to make their story known. Their ability to engage with American institutions, whether it was the political system or the news media, was enhanced rather than diminished.

INTERVIEWER

What was the perception of the US about Arabs and vice versa in the 1970s?

YAQUB

The main change that occurred in the 1970s is that Americans and Arabs became more familiar with each other. There are a number of reasons for this. The nature and extent of US involvement in the Arab world increased substantially from the late 1960s. On the one hand, the power of Britain and France had significantly diminished over the previous few decades following the era of decolonization. Also, the Arab-Israel War became more important from a global perspective. In other words, after the 1967 War, the international community as a whole became more concerned about that conflict and more interested in resolving it. The United States as the leading Western power became much more involved in that conflict as well. It essentially replaced France as the primary supporter of Israel in terms of military aid. As the US became more involved in supporting Israel, it also became more involved in efforts to resolve the Arab-Israeli conflict. The role of the United States was becoming a lot more visible and prominent in the Arab World. A similar thing was happening for Americans in the 1970s and their knowledge of the Arab World. A number of crises took place–mostly involving the Arab-Israeli conflict–that brought the Arab World to the attention of Americans. For example, international terrorism was increasing, in which some Palestinian groups participated. Of course, these events gained a lot of attention from the news media, and from time to time Americans themselves were the victims of Palestinian terrorism. Similarly, oil issues become more important because the dependence of the global economy on Middle Eastern oil increased and because of a series of events in the 1970s, especially as a consequence of the 1973 Arab-Israel War. The Arab oil embargo of 1973-74 caused disruptions in the distribution of oil throughout the industrialized world including in the United States. There were long lines at gas stations. So people were affected in their daily life by the politics of the Arab World. The main transformation, I argue, is that these two societies became more enmeshed with each other.

INTERVIEWER

If we focus on the sociology of Arab-Americans in the US, we see the role of important Arab-American organizations such as the Association of Arab American University Graduates (AAUG) and the National Association of Arab Americans (NAAA) is struggling against defamation of Arabs. What was the importance of these organizations for the visibility of Arabs in the US?

YAQUB

They were important in that they were able to cooperate with other Americans who held similar views in bringing new perspectives to the national discourse. For example, the Palestinian issue–the notion that Palestinians were a national group who had national aspirations as opposed to simply being a group of refugees whose political aspirations should be fulfilled in other Arab countries– had in previous years not really been given any significant attention in the United States. By the late 1970s there was a perception within the American mainstream that yes, the Palestinians did have a case that needed to be addressed. This did not necessarily translate into support for Palestinian aspirations or for significant sympathy for the Palestinians, but there was recognition that this was an issue that needed to be resolved. Hence, what happened was that Arab-American groups and other groups of Americans who shared their perspective were able to put certain issues on the national agenda in the United States in ways that had not occurred in previous years.

INTERVIEWER

How did Arab-American activists react to the Camp David accords of 1978 that purported to provide a framework for peace in the Middle East?

YAQUB

I would say that for the most part Arab-Americans were disappointed and even hostile to the Camp David accords. Initially, there was on the part of some of the more modern Arab-Americans groups (for example, the NAAA) some willingness to give this process a chance and to see if an agreement between Egypt and Israel could lead to a broader settlement involving other Arab actors especially the Palestinians. But very soon after this agreement was announced it became clear that the agreement really was not going to lead to anything broader, that it was essentially a bilateral agreement between Israel and Egypt. Moreover, Egypt got what it needed in terms of getting the Sinai Peninsula back and in exchange for that it extended recognition to Israel, basically withdrawing from the Arab coalition that had opposed Israel. The problem from the point of view of Arab-Americans was that this greatly strengthened Israel's ability to hold on to the remaining occupied territories. Now, Israel no longer had to worry about whatever diplomatic threat Egypt posed to Israel and that meant that Israel was much freer to consolidate its occupation of the Golan Heights, the Gaza Strip, and the West Bank. Also, Israel was starting to dominate at this time in southern Lebanon. From the standpoint of critics of Camp David, the agreement did not move the parties closer to a final settlement but rather made the final settlement even harder to reach because Israel had very little incentive to negotiate seriously with the remaining Arab actors. Hence, Camp David was strongly and widely opposed by groups like the Association of Arab American University Graduates (AAUG) and the National Association of Arab Americans (NAAA).

INTERVIEWER

What was the role of religion in the US-Arab relationship in the 1970s?

YAQUB

Actually, I do not see religion as a very important part of the overall US-Arab relationship. Religion became much more important in subsequent decades in large part because of transformations in the Arab World where Islamism became much more powerful and secular nationalism was weakened. However, these are transformations that took place primarily after the 1970s, so I do not address them in great detail.

INTERVIEWER

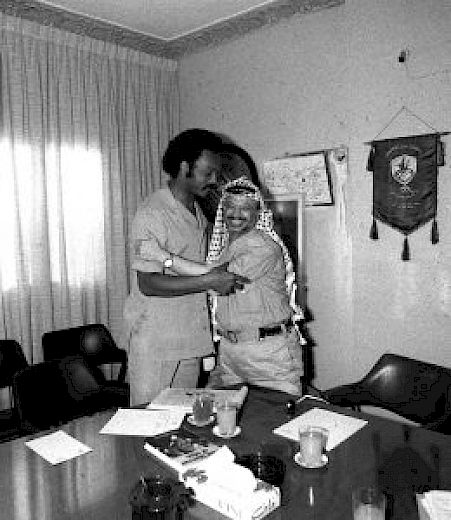

Please tell us about other ethnic groups' perceptions of American policy toward the Middle-East? For instance, we know about the meeting of Jesse Jackson and Yasser Arafat.

YAQUB

One of the stories I tell in the book concerns the transformation in African-American perceptions of the conflict. In the early years of the 1970s most African-Americans, like most Americans, generally tended to be sympathetic to Israel. However, that changed for a number of reasons–some of them having to do with new relationships between Israel and Apartheid South Africa, which aroused a lot of criticism among black Americans, and also as a consequence of outreach efforts that Arab-American groups made to African-American organizations. What you see in the second half of the 1970s, and especially at the end of the decade is a new movement of criticism of Israel among African-Americans. I should point out that for years that had been a subset or a small part of the African-American community that was very critical of Israel. For example, the Nation of Islam (the so-called Black Muslims) and also some of the more radical black power groups like the Black Panthers had long been very critical of Israel seeing it essentially as an arm of Western imperialism and colonialism and so forth. Mainstream African-Americans who still regarded Israel as legitimate nevertheless became more willing to criticize Israel and to say that it was essential for Israel to make room for the Palestinians and for the conflict to be resolved perhaps by creating two states: Palestine and Israel.

INTERVIEWER

In the book, you mention that Arabs donated money to American universities like Princeton, Harvard and the University of Texas to set up programs in Middle East studies. How was this process politically managed by the US government?

YAQUB

That is a really interesting topic! As a consequence of some of the transformations that I mentioned earlier, including the increasing dependence of the global economy on Middle Eastern oil, the price of crude oil essentially quadrupled in late 1973. Even after the Arab oil embargo ended, oil prices remained at a new high. What this meant was that oil-rich Arab countries had much higher revenues than they did before. Hence, they just had huge amounts of money to spend and what many of them did was to invest this money in the United States. In the second half of the 1970s, there was a very substantial increase in Arab investment from both Arab governments and from Arab private actors in the United States. As I said in the book, on the one hand, this does generate antagonism where many ordinary Americans, some elite organizations, and even some American leaders argue that wealthy Arabs are "buying up the country" and posing a threat to American independence. The US government, for the most part, did not share this view, including the Department of Commerce, the Department of Treasury, and the State Department. These departments and agencies generally saw Arab-American investment in the United States as a good thing. On the one hand, they thought it was beneficial for the US economy at a time of considerable economic stress. On the other, US state departments and agencies that were concerned with foreign policy believed that it was better for global stability for the Arab states to invest in the US economy. If you have many Arab countries investing lots of money in the US economy, then they have a stake in the success of the US economy. So they are less likely to impose another oil embargo or engage other forms of economic warfare against the United States because they will also lose. In general, the US government encouraged the circulation of petrodollars in the United States.

INTERVIEWER

What is the state of Middle East studies in American academia today, especially after Edward Said?

YAQUB

Edward Said's book Orientalism and the number of his other articles, books, and essays have significantly transformed the way the Middle East is studied in academia. I guess, in general, you could say that there is a much more critical perspective on the United States and the West within academia, a growing tendency to see the harmful impact of Western colonialism and imperialism on the societies of the Middle East, and a more critical view of US power, and a tendency to see the policies of the US as having more in common with the imperialist policies of previous world powers. Also, we see a tendency to sympathize with the political and cultural perspectives of Middle Easterners in some pockets of American society. There is a fairly distinct gap between how the Middle East and the Arab World are portrayed in the national media or entertainment, on the one hand, and how these topics are discussed in academia. In that sense, academic perspectives are not really representative of the broader cultural perspective of ordinary Americans.

INTERVIEWER

What were the effects of events in the non-Arab world (such as the invasion of Afghanistan, the Iranian Revolution, and the Iran-Iraq War) on the Arab-US relationship?

YAQUB

What I argue in the book is those general events in the 1970s created a great deal of instability in the United States and in the Middle East, and as a consequence of that you have more violent and hostile relationships between the United States and much of the Arab World. A big part of that was a consequence of diplomacy around the Arab-Israeli conflict. As I suggested Henry Kissinger created the situation in which Israel was able to hold on to the territories occupied in 1967. This created a great deal of anti-US sentiment in the Arab World and also a great deal of other upheavals where you have increasing hostility towards the West on the part of Arab actors. This was exacerbated by events taking place outside the Arab World, especially at the very end of the decade. The Iranian Revolution, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the outbreak of Iran-Iraq War created new forms of instability in the broader Middle East. As a consequence, the United States became more willing to intervene with military force. Prior to the 1980s, the United States avoided sending military forces into the region for fear of the Soviet Union's reaction. As you move into the 1980s and beyond, a couple of things were happening, on one hand, the Middle East as a whole was becoming more unstable and new threats were emerging for the United States. On the other, the Soviet Union lost power. Hence, the United States felt that it could intervene militarily without worrying how other superpowers might react. As a consequence, the instability in these peripheral areas to the Arab World such as Afghanistan, Iran, and the Persian Gulf was part of a broader process whereby the United States was becoming more and more willing to use military force. That change helps us to understand the situation that we face today in which the US is heavily military involved in the parts of the Middle East.

INTERVIEWER

What are your plans for the near future? What have you been working on recently?

YAQUB

That is an open question right now! In the near future, I will be probably be working on a general history of the US since World War II–something that looks at what was taking place within the United States domestically but also looking at the US role in the world since 1945. Also, I am thinking of studying US involvement in Lebanon in the 1980s. In this period, we see the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the deployment of US marines to that country as a consequence of that invasion and then the tragic bombing of the Beirut Marine Barracks in 1983. Also, US-Lebanese relations became very prominent in the 1980s. In other words, the 1980s are an interesting period in which Lebanon became important for the United States.