Sharing the Burden: An Interview with Charlie Laderman

By training, historians tend to avoid musing too much on what might have happened. Yet, counterfactuals can serve an important purpose: they illustrate by contrast the consequences and meanings of what actually did happen in a particular stretch of time. In his recent book, Sharing the Burden: The Armenian Question, Humanitarian Intervention and Anglo-American Visions of Global Order, Charlie Laderman examines a period of history that is rich in contingencies and alternative outcomes, casting light on a weighty moment in the development of the international system as we know it.

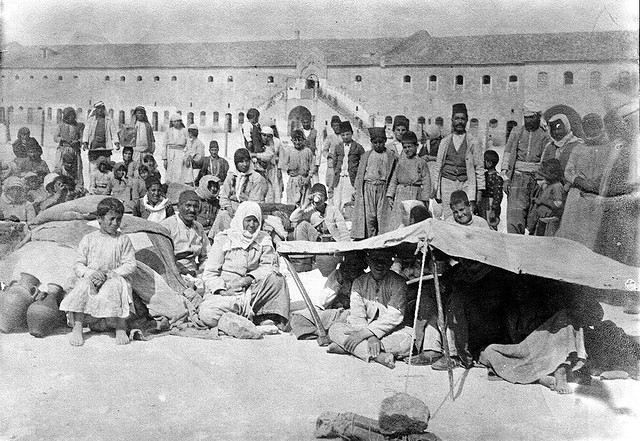

Drawing on research in U.S., British, and Armenian archives, Sharing the Burden looks at the evolution of the relationship between the United States and Great Britain from roughly 1894 until 1919. What was known as “The Armenian Question,” a complex knot of dilemmas pertaining to humanitarian intervention, empire, and the evolution of international cooperation, arose time and again in these years, as Armenian people suffered successive massacres under the crumbling Ottoman Empire. At the start of Laderman’s book, the United States still relied on missionary groups—not ambassadors—as its representatives in many parts of the world, and the Sublime Porte in Istanbul still controlled most of the Middle East; by the end, the United States is firmly ensconced as a great power, the League of Nations has been both formed and rapidly undermined, and European colonial mandates controlled much of the Middle East. Sharing the Burden provides a vivid window into these significant transformations, all while charting how various U.S. presidents, missionary leaders, and British officials responded to the question of humanitarian intervention to save the Armenians. Along the way, Laderman brings to light many forgotten projects of the period: an Anglo-American colonial alliance, the drive to establish a U.S.-controlled mandate in Armenia, and the salience of the Armenian question for the American public—tantalizing counterfactuals, indeed.

Charlie Laderman is a Lecturer in International History at King’s College, London and part of the leadership at KCL’s Centre for Grand Strategy. He is also a Senior Research Associate at Peterhouse, University of Cambridge. Sharing the Burden won The Society for Historians of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era’s H. Wayne Morgan Prize in 2021. In addition to Sharing the Burden, Laderman co-authored Donald Trump: The Making of a Worldview, with Brendan Simms in 2017, and the forthcoming Hitler’s American Gamble: Pearl Harbor and the German March to Global War, also with Brendan Simms. In our conversation, which has been edited for clarity and length, we discuss how he came to be interested in Armenia, the role of public opinion in policy making, and how the Armenian question persists to this day.

—Emily Whalen (The University of Texas at Austin)

Emily Whalen: Armenia is a tiny country, and its history is occasionally seen as kind of a niche interest, but your work places it in a much broader, more international context. Tell me a little bit more about how you came to the book’s subject.

Charlie Laderman: Yes, I find people often assume I have Armenian heritage, but I do not. I came to the subject as someone who was fascinated with U.S. history in the late 19th and early 20th century. While studying as an undergraduate at the University of Nottingham, I became fascinated with the Progressive Era, particularly with the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson.

I think you become interested in historical topics for different reasons—sometimes because it seems similar to your current experiences. For me, this period of time in the United States felt alien. A figure like Theodore Roosevelt is nothing like anything we see in British political history. So, I wanted to study U.S. history in more detail, and I went to Cambridge to do that.

My master’s degree supervisor at Cambridge was Brendan Simms, who was putting together a colloquium when I got there on the history of humanitarian intervention with David Trim. That ended up becoming a book (Humanitarian Intervention), one of the first real histories of humanitarian intervention. I was helping to organize that, and though I’d come to Cambridge to do straight diplomatic history, I began to wonder what topic in humanitarian intervention I might do for my master’s dissertation. I started to read about the subject, particularly Samantha Power’s book, A Problem From Hell and Gary J. Bass’s Freedom’s Battle.

I’d come of age politically in the 1990s and early 2000s when there were big debates over interventions, first in the Balkans and Rwanda, and later in the Middle East. What struck me about the Bass and the Power books was that the Bass book ended with the Armenian issue, and the Power book began with it. It seemed to me to be an important turning point in American history and in international history, but when I was reading books about U.S. foreign policy in this period, the Armenian question just wasn’t there. It wasn’t there in the literature on foreign policy, and it wasn’t really being discussed outside of the genocide itself in histories of the First World War. The more I dug into it, the more I realized that the Armenian issue was much broader, and actually had a significant impact on discussions about international society and international politics, about America’s place in the world, and about British empire and Britain’s relative decline. It seemed like Armenia was a window into these broader issues.

The more I dug into it, the more I realized that the Armenian issue was much broader, and actually had a significant impact on discussions about international society and international politics, about America’s place in the world, and about British empire and Britain’s relative decline. It seemed like Armenia was a window into these broader issues.

EW: Have you read Eric Weitz’s AHR article about the Paris and Vienna systems? The way you describe it in the book, the Armenian issue seems like an inflection point in the transition Weitz describes from a system of state sovereignty, the “Vienna system,” into what Weitz calls the “Paris system,” which ties human rights to ethnic or religious identity. Is that a fair assessment?

CL: Yes, that’s accurate—when I read the Weitz article in graduate school, it set off all sorts of bells and lights for me. It highlighted what I was trying to work out at the time, which was how some of the debates over what was going on in the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the century related to issues of international cooperation and humanitarianism. He talks about what went on in Central Africa and the Congo around the Berlin Congresses of 1870s and 1880s, and that supported my sense of the issue as a broad, international question. The Congresses were happening around the same time that the Armenian Question emerged as a major diplomatic issue. The security of the Armenians soon became an international humanitarian cause célèbre, the latest national independence struggle of a subject people in the Ottoman Empire to attract widespread popular appeal in Europe and North America.

I was trying to avoid anachronistically looking back into history and, for example, finding the origins of what we might come to call the “responsibility to protect” doctrine—I wanted to look at this history on its own terms. Obviously, the term “intervention” is very much a live one in the 19th century, so the Weitz article was extremely useful because it discussed both connections that were drawn by actors at the time but also by historians of human rights at the time looking back at what was going on in Africa and the Middle East and using that perspective as a touchstone in some of these debates.

EW: What jumped out at me in your book was in part how, while negotiating the legacies of different colonialisms—both Ottoman and European—the dividing lines that open up don’t follow along national boundaries, but actually within societies. For example, as you relate, the U.S. missionaries in Armenia aligned more often with British officials than with U.S. officials, which might be surprising to some. It reminded me of Erez Manela’s work, both in The Wilsonian Moment and his recent article on international society.

CL: Yes, The Wilsonian Moment, was another very influential text as I was starting this project. What brought me to look at Armenia in part was the fact that as these major conversations are going on in China, Korea, Egypt and India over the Wilsonian ideal, as Manela describes, the Ottoman Empire and Armenia specifically was the one place the United States was actually thinking about taking on a formal role and strategic responsibility for territory. In some senses, my book is building on what Manela does in The Wilsonian Moment. I thought Armenia was an interesting case study that offered something slightly different to what he outlines.

The concept of international society has been important, too. In some senses, I started this as a more traditional diplomatic history study, but the more I worked on it, the more I realized you couldn’t keep the subject within those boundaries, and you needed to understand not only transnational factors, like the missionary movement, and the broader cultural trends of Anglo-American solidarity, but also nascent nationalist organizations like the Armenian groups that emerge in the diasporas and which try to influence policy in the United States and Britain. When you start to consider those transnational groups, the story changes. The missionary groups are as international actors as you get in in America at this time, and the United States has a larger missionary presence in the Ottoman Empire than any other nation in these years.

EW: The missionary groups as you describe them are almost paradoxically cosmopolitan: on the one hand they are very parochial in that their interest in these foreign countries is extremely bounded in religious conversion, but then actually living in foreign countries, they become much more international.

CL: They’re fascinating. The archives for missionary groups are so rich—I spent quite a long time in the Houghton Library at Harvard and at Yale Divinity School going through missionary archives. You really get a sense of missionaries as observers of foreign societies, but there is also a lot about what they transmit back to the United States. They’re internationalizing figures who have as much influence on the American mind as on the societies they seek to convert.

Because they had interests in a certain kind of conception of global order—they were relying on British power, particularly naval power, to keep them protected in the Ottoman empire while pushing the boundaries of what they could get away with—their missions are quite nuanced. They go to the Ottoman Empire to proselytize to the Muslims, but when it becomes clear that, because of Ottoman apostasy laws, they won’t be able to focus on conversion, they then focus on building up these Gregorian Christian, or ancient Christian communities. The missions seek to infuse Near Eastern Christians with a New World Protestantism, to serve as a beacon to the rest of the region. Now, they never forget that original mission, of converting Muslims, and that is what leads to major challenges down the line. The Armenians (a mostly Christian community) are their wards, but their larger goals are beyond the Armenians, which leads to complex and challenging debates when massacres begin to break out.

EW: One of the things I found striking in the book was your description of these challenges that missionaries face when it comes to their aspirations clashing with reality. It’s almost as if these groups of missionaries, much like many U.S. presidential administrations you describe, were reckoning for the first time with the double-edged sword of public opinion.

CL: The role of public opinion in this period is so interesting. In the Gilded Age and the aftermath of the American Civil War, to a certain extent, the United States was actually more diplomatically isolationist than it had been previously. There were a lot of old traditions around the Monroe Doctrine and avoiding entangling alliances brought out like holy writ. But at the same time, there was a deep cultural fascination with the rest of the world: this as the time of the “grand tours” and people were reading voluminously, consuming travel journals about the rest of the world. There was also a particular interest in the Middle East. So, a tension arose between the cultural fascination and, simultaneously, a desire to avoid responsibilities to the rest of the world.

The missionaries, in order to encourage philanthropic giving and political interest in the region where the United States didn’t have a diplomatic presence, really played up anti-Ottoman sentiment. They played a double game, trying to both encourage philanthropic giving for funds for their missionary activities, but at the same time, not antagonizing the Ottoman authorities too much, so their properties wouldn’t be seized—as they were at the time of the first Armenian massacres in 1894. The missionaries wanted to maintain their position in Ottoman society while increasing U.S. interest in Armenia.

During the First World War, once the United States did intervene, there was a great deal of pressure outside the missionary community, on Wilson to expand the United States’ military position in the war, to move beyond the Western Front. It’s often forgotten that Wilson never actually declared war on the Ottoman Empire during WWI, despite a lot of public pressure to do so.

The missionaries backed Wilson’s position, but they were almost made captive by their position and propaganda prior to Wilson’s decision—if the Armenians were the victims of these massacres, why shouldn’t the United States intervene to put an end to them? That becomes a really fractious and live debate in American society during the First World War.

EW: Teddy Roosevelt as you describe him had a much grander vision of the United States taking on responsibility in the world, and his blustery political rhetoric reflected that. Yet in reality, when it came to policy, he couldn’t do very much. How does the Armenian question change our understanding of Roosevelt?

CL: For a figure like Roosevelt, who is seen to be this great activist president, the challenge comes with seeing him having to deal with a society that was much less willing to take on this global role than he was. He tried at many times to push Americans to become more activist and more interventionist at various points in his presidency. Certainly after his presidency he was the leading advocate of American intervention in the Ottoman Empire.

Intervention was part of his vision of the civilizing role the United States should play in the world in concert with the British Empire, to spread order, to spread their values, to spread Anglo-Saxonism, to spread Christian values – all of these things were caught up in this rubric of “civilization.” Yet at the same time he had to recognize the limits of that. Both Roosevelt and Wilson were dealing with this dilemma in different ways.

Missionaries, although outside of public life, were very influential as lobbyists, and they were often operating in places where the United States had no or very little diplomatic presence. The American public tended to see them as the United States’ representatives when crises broke out in certain parts of the world—particularly during the 1910 revolution in Mexico, the revolution in China in 1911, and the Young Turk revolution in 1909. In these revolutions, there was a sense too that these societies were re-imagining themselves in the American image, and U.S. missionaries were seen locally as the gatekeepers to that image. One of the things I tried to do in the book was to look at solutions to the so-called Armenian “question” and the missionaries are very much supplying ideas for solutions to political leaders at the time.

EW: Perhaps a slightly unfair question, but what was, in your view, the “Armenian question”?

CL: It’s one of those things that is not immediately obvious when you come to the topic for the first time. Holly Case’s interesting book positions the 20th century as the “age of questions”—there were so many questions in the public realm, the “Eastern question,” the “Jewish question,” the “question of women’s rights,” etc. The Armenian question is sort of a sub-stratum of the Eastern question, which had to do with the problem of what would happen with the Ottoman Empire as it started to degenerate and collapse.

In its simplest sense, the Armenian question was about the issues that arose from the insecurity of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. But it came to be much broader than that in the public imagination. In many senses it became a shorthand diplomatic term, a metaphor for questions of America’s global role, and the relationship between the United States and the British Empire (in part because the two powers, more than anyone else, took a strong interest in the Armenian question). The Armenian question was also saturated through with questions of religiosity and of race—the Armenians were often described at the time as the “Anglo-Saxons of the Middle East.” The Armenian people come to occupy a highly symbolic role in the public realm.

In many senses it became a shorthand diplomatic term, a metaphor for questions of America’s global role, and the relationship between the United States and the British Empire (in part because the two powers, more than anyone else, took a strong interest in the Armenian question). The Armenian question was also saturated through with questions of religiosity and of race—the Armenians were often described at the time as the “Anglo-Saxons of the Middle East.” The Armenian people come to occupy a highly symbolic role in the public realm.

EW: After reading your book, I think a dimension of the Armenian question was the question of whether the United States was going to step fully into its role as a world power. It kind of seems like the answer was “no”—do you agree?

CL: This subject has about it the air of a counterfactual, a sense of what might have been. When I was working on the book, I thought about it a lot—particularly over the question of what might have happened if the United States had taken over a mandate in Armenia after WWI. The book is, in a sense, the story of something that didn’t happen.

Yet, even though it didn’t happen, the subject is still consequential—Armenia’s fate infused the debate over the League of Nations. I’d say you can’t really understand the debate over the League of Nations without understanding it in relation to the mandate debate, because governing a mandate over Armenian territory was the concrete commitment the United States might have taken on under the League. Certainly at the time, people saw the two as being very much interlinked.

There are many times in the narrative where you think “Perhaps [the U.S. mandate over Armenia] is about to happen!” In early 1919, the U.S. mandate was a big part of Woodrow Wilson’s vision, it was going to be the vehicle through which the United States actually takes on its global role and global responsibilities. But ultimately, in hindsight, the U.S. mandate in Armenia looks always like a quixotic project, never likely to come about. At each point, there is far more pushing against it than pushing for it.

EW: Embarrassingly, I did not even know that the proposal for the United States to take over a colonial mandate in Armenia was part of the League of Nations debate! Although I work on a later period, the mandatory system has huge ramifications for the late 20th century Middle East, and I just can’t believe I never knew the U.S. might have been a mandatory power there.

CL: You could read a lot of books on this and not really see anything about it. What struck me about the mandate debate in the American political space, as I began to research it further, was how important it was to the debate over the League of Nations in general. The mandate system, and in some senses the League of Nations itself, was designed with the idea of having the United States at its center. British figures like Jan Christian Smuts or David Lloyd George, particularly those around the Round Table movement of imperial reformers, were very focused on establishing an Anglo-American colonial alliance, and the United States taking a mandate was absolutely fundamental to this idea. The United States couldn’t just join this abstract notion of an international organization, it needed to take on specific responsibilities.

So although it’s something that doesn’t happen, the mandate debate does shape what comes afterward. Ultimately the League of Nations is designed with this responsibility at its essence, and when the United States rejects its role, the League ends up having to continue without its raison d’être.

EW: I did want to talk a little bit about Britain’s role and how Armenia becomes a symbol in the renegotiation of the relationship between the United States and Britain in this period. Is the Armenian question a point of rupture or a point of continuity between Washington and London?

CL: Right from the outset, as a rapprochement between the British Empire and the United States became evident, the Armenian issue became a vehicle that British policymakers used to encourage the Americans to take on a certain global role, to make them sympathize with the British global mission. Starting with the first large scale massacres in Armenia, in 1894 and 1896, there were attempts by the British to get the United States to embark on a joint intervention, attempts that continued during the Roosevelt administration.

Once the United States intervened in WWI, the British put more emphasis on the treatment of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire—the Armenian question really crystallized in that period after WWI, and was seen as the opportunity to establish an Anglo-American alliance that British policymakers, since the 1890s, had held up as an ideal. Duncan Bell writes about the idea of the alliance as a racial union, but I think it goes beyond race—religion, specifically Protestantism, was really fundamental to the Anglo-American alliance, too. So, Armenia became the crucible through which a new international order would be established, with the United States and British Empire acting together as its foundation. British leaders thought of the mandate as a way to get the United States to act on Wilson’s idealistic rhetoric.

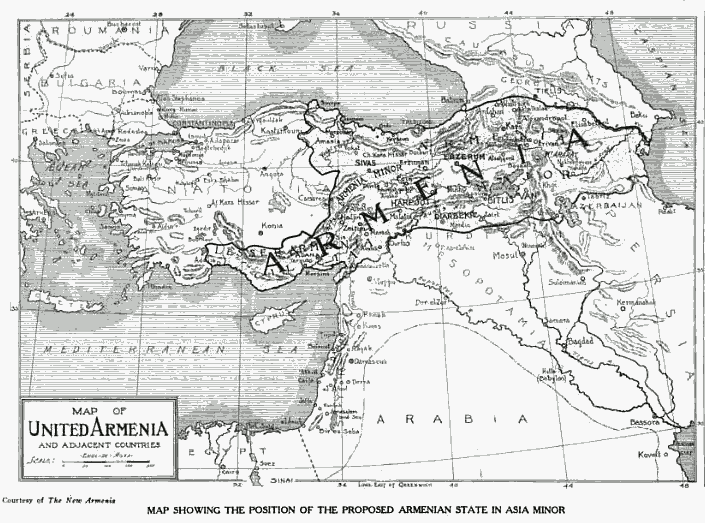

In fact, at Versailles in 1919, in conversations between Wilson and the British, it’s clear the British didn’t really care where the United States entered into this alliance. The Armenians themselves were not that important to this British vision. The British suggested Wilson draw the boundaries of U.S. involvement where he wanted to. We think about Armenia today as a small state up in the Caucasus, but the historic territories in which Armenians lived stretches from the Caucasus to the Mediterranean. A vast area, geopolitically significant, and the British just wanted the Americans there in 1919, partly for strategic reasons (to guard against threats to the Suez route to India), partly to offset the French, and partly because they were committed to the idea of the League of Nations being an Anglo-American alliance. So throughout that period Armenia was both a metaphor and something quite tangible—something to hang the rest of the system around.

To a great extent, I would say the Armenian question represents a rupture in Anglo-American relations—more rupture than continuity. There was a very clear period from the mid 1890s to 1920, in the history of the United States in the world, that started with the first Armenian massacres, debates over the Spanish-American war, and intervention. It ended with the aftermath of the debate on the League of Nations and the rejection of the Armenian Mandate. This is a set period in terms of America’s rise as a global power, and its rejection of global leadership.

In another sense, the Armenian question represents a continuity, because the reverberations of the U.S. decision to remain aloof will be felt throughout the 20th century. One reverberation was the sense on the American side that they were being taken advantage of by the British, that the British were using American idealism for their own purposes—there were a number of American figures who never forgot that, in their perception, the British took over the most lucrative mandates and tried to get the United States trapped into a backwater. This grievance was constantly brought up by figures like Herbert Hoover and others on the right of the American political spectrum.

There was also a continuity in the method of global governance. Despite common understandings of the mandate system as a fig leaf for imperial nakedness, the mandates were a transformative method of global governance. In order to get the United States, which didn’t have the same European imperial sensibility, to buy into the system, the great powers did have to make certain compromises. The United States’ view of the mandate system was much more reflective of classic progressive liberal views at the time – that exploitative imperialism and imperial competition were the seeds of international conflict. Wilson’s whole vision of the mandate system was based in the idea that the United States could show the rest of the world how to do empire “properly” – as a form of “trusteeship” that would serve as a tangible manifestation of a US-led international order.

EW: Would you say these years are setting the tone for what will become known as the American century?

CL: I was loath to look back on these debates through the lens of American interventionism in the late 20th century, but it’s very difficult not to see the parallels. The arguments of the major American advocates of a mandate in the Middle East were framed as the responsibility of an international community to not only prevent crimes against humanity, or what would have been described then as “civilization,” but also to participate in a nation-building effort. Of course, to speak of concepts such as “responsibility to protect” and “nation-building” in this era might seem anachronistic—but these were terms that were actually being used at the time. The mandate system was understood by some of its leading proponents as a vehicle for “humanitarian intervention.” It didn’t end up becoming that, but the language and ideas are there at its infancy.

EW: You address in the book the role that race played in the Armenian question, but I wanted you to go into a little more depth on gender—it seems there are hints of a sharply gendered world view in these debates on global order but it rarely comes out explicitly.

CL: I mean, it’s difficult to talk about Theodore Roosevelt without bringing up conceptions of gender and masculinity, as Kristin Hoganson’s book illustrates. In regard to Armenia, General James G. Harbord, the American Chief of Staff on the Western front during WWI, oversaw a 1919 report on whether the United States should take over a mandate in the former Ottoman Empire. In his report, you see that gendered conception of the world, calling the mandate over Armenia “a man’s job.” There was a strong sense of proving the virility of the United States, and its usefulness—gendered language saturates these debates at the political level.

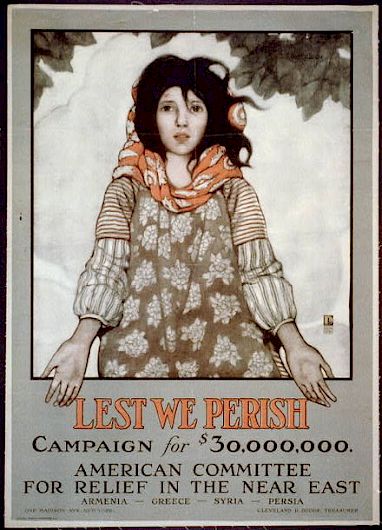

On the other hand, gender played an interesting role within the American philanthropic and missionary community. Near East Relief was one of the largest private philanthropic organizations in American history, and it was a successor to some of the relief organizations that form in response to the first massacres in Armenia in the 1890s. The leading figures in that movement were people like Julia Ward Howe, who became famous for writing the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and who was a famous women’s suffragist. Clara Barton took an American Red Cross mission to Armenia. The spokespeople for action for the Armenians are not just making the case for intervention in the masculine language of “duty” and “honor” – humanitarian intervention was also a venue for women to establish for themselves roles in public life. It was an acceptable space for women to express their agency.

Another interesting way gender played into this story, to go back to the missionary role, is through the Constantinople College for Girls. A missionary institution, it was one of the first institutions in the Near East for women. Halidé Edib, who was a Turkish feminist and a Turkish nationalist linked to Mustapha Kemal got her education there, and when there was discussion about the United States taking on a larger mandate, covering more of the Ottoman Empire than just Armenia, Turkish nationalists like Mustapha Kemal were actually relatively sympathetic to the idea. Kemal felt that the Turkish nationalist project was in real danger in mid-late 1919, and Edib, coming out of this American missionary college, encouraged him on the idea that perhaps the best situation for Turkish nationalism was for the United States to come in as mandatory ruler, and not the British or French, who might have carved up the territory in different ways; she saw that the Americans would provide economic benefits and may not stay on in the region in the same way the Europeans seemed likely to. Edib was certainly influenced in her sense of sympathy to the Americans by her experience at Constantinople College for Girls.

EW: I read your book during the summer of 2020, right around the time that the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Nagorno Karabakh saw a resurgence. Is there a 21st century Armenian question, and if so, is it different to the one we saw at in the 20th century?

CL: There’s a clear echo between what happened to the Armenians in 1918 and what is happening to the Armenians today—Thomas de Waal has written a bit about this. What is similar is the way in which the Armenians place their faith in the international community, and in the United States specifically. Ultimately, we saw, in a similar way as in 1918, the possibility of an independent republic of Armenia crushed between Soviet and Turkish expansion, with the Armenians again looking to the outside world for help, not receiving it, and as a result, are left defenseless.

The strongest parallels are the sense of U.S. withdrawal from interest in that region, and in the ways that rhetoric and policy don’t align in the United States. Last summer, Congress and other leaders talked a lot about action in Armenia, which ultimately didn’t come about—indeed, we saw something similar to the Kurds in Northern Syria, too, in the early 2010s. What was also surreal was that the war broke out around the time that Congress formally recognized the Armenian genocide of 1915, so the public consciousness of the parallel was quite strong.

What I tried to get at in the end of the book is that there are certain dilemmas in terms of America’s engagement with humanitarian issues that come up again and again: how do you ensure your rhetoric doesn’t run away from reality? How do you ensure that you don’t make commitments you can’t fulfill? This is something that Theodore Roosevelt warned against in his presidency when he was being lobbied on behalf of Russian Jews who were being persecuted in the pogroms. He famously said that his philosophy on these issues for the United States was “Don’t draw unless you mean to shoot.” This is an abiding lesson that is brought up again in the 1920s when there is pressure on the U.S. government around the time of the burning of Smyrna—the Secretary of State in fact uses those exact words. It’s something you see again and again, this question of “are we promising something we can’t deliver?”

Another major dilemma centers on the question of “how should the United States act in the world?” Should it work through international organizations? Currently, it doesn’t seem to be likely for the United Nations or another international organization to be able to act in situations like you see in Armenia today. Theodore Roosevelt was also grappling with the question of using multilateralism, much more interested in using what would later be called a “coalition of the willing”—working with other like-minded actors to shape the world.

When talking about echoes of history, particularly with a topic like Armenia, there is a sense of an overarching tragic narrative: sometimes there are limits to what a particular nation can actually achieve. Sometimes, there are no good solutions. It’s not entirely clear how the United States could influence events on the ground in Armenia, even though Washington has a much larger role in the world today than it did in the period I’m looking at in the book. But some of these strategic dilemmas haven’t really gone away.

EW: You mentioned at the beginning you were drawn to study the Progressive Era because it seemed so remote from our present moment. Do you still feel that way?

CL: It does feel more familiar now than it did when I first started. You know, figures like Roosevelt are still quite alien, but in another sense some of the issues that he was focused on, like trust-busting and, of course, discussions over America’s role in the world, are certainly abiding debates.

As the international scene has become more fractious it’s difficult not to see the turn of the 20th century—particularly the strategic competitions in different regions—as having certain resonance. The way in which religiosity saturates political debates in the Progressive era, I think we have moved more away from, even over the last one or two decades, but the fundamental questions remain.

For both the British and the Armenians, there is a sense of how their interests are fundamentally served by getting the United States to take on a more global role. There are still some echoes of that today. Despite the criticism of the United States being overly active in the world, there is also a great deal of concern about the United States turning too far inward. A lot of the rhetoric we saw in the U.S. after January 2020 reflects that concern, the “getting back to normal” narrative, and America turning back to world. Other nations, as critical as they are of America’s behavior, at times want to see the United States act in the world—most of these actors see a larger role for the United States as being more in their interests. That is something that is really similar to the early 20th century.

I’ve been doing a lot of work in the applied history space, and to me, applied history is less interesting in the sense of looking to the past for clear lessons and answers, and more interesting in the sense of looking into the past to see people engaging with similar dilemmas to the ones we’re facing today. And yes, although the early 20th century was a period of more formal empire, many of the discussions going on about how you navigate sovereignty, the role of states in terms of nation-building, and the role of an international society, overlap with those we are undertaking today.

People think, “Armenia is a small little state, why do we care what’s going on there?” But if you look at Armenia in the early 20th century and see how engaged world leaders were with its fate, you can see how Armenia was this metaphor for broader strategic considerations. If you allow instability in to grow in far-flung regions, if you allow great crimes to go unpunished in tiny countries, there will be serious echoes far along down the line.