Sandalwood Commonwealth? Traveling Across a Chinese-Australian Pacific with Sophie Loy-Wilson

Scan the news these days for news from the western and southern Pacific, and it doesn't require too much reading for the outlines of a multipolar future to emerge. There are, of course, the obvious stories: competition between the United States and China; that relationship's reverberating effect on the Korea-Japan-China triangle; and the effect of a dynamic and rising Vietnam and Indonesia on what is likely to be the main engine of global economic growth in years to come. Sometimes obscured through a focus on the areas of Northeast and Southeast Asia, however, can be the important role that Australia plays in the broader region. While party to numerous strategic agreements with other Commonwealth countries and the United States, the world's twelfth largest economy plays a role as a key trading partner for China. Indeed, one of the major ongoing debates within Australian politics is how this former Dominion, so far from "old" British and former Imperial markets and so close to a region with a near-unlimited appetite for raw materials (plenty of those in Australia's arid interior) should balance between the Angloworld and the East, China in particular.

Such debates about Australia's economic, political, and to some extent cultural orientation have, of course, not only a history of their own but are themselves influenced by the work of journalist, scholars and activists on the meaning of Australia's place in the world. And it's precisely because of her contribution to these debates that the Toynbee Prize Foundation sat down recently with Dr. Sophie Loy-Wilson, a member of the Laureate Research Program in International History at the University of Sydney.

Refreshingly for a country whose political culture can sometimes play up images of Australia's aloofness from a wider Oceanic and Asian world, Loy-Wilson seeks to unearth the often obscure history of Chinese-Australian relations from the nineteenth century to the present day. Using Chinese, Australian, and British sources, her work locates business history and cultural history in a transnational context to examine the web of exchange and ideas about the other in which Chinese-Australian relations have formed for nearly two centuries. Such a package of skills and interests is no doubt likely to make hers a voice to watch from Beijing to Canberra for years to come. It also made for a stimulating conversation as we sat down with her recently to discuss her intellectual formation and her ongoing scholarly work.

•

We begin our conversation with a discussion of Loy-Wilson's journey to history as a profession. Born to an Australian diplomat who specialized in Soviet affairs, Sophie was born in West Berlin hospital whilst her parents were stationed at the Australian Embassy in Warsaw–given the state of the country's hospitals at a time of massive foreign indebtedness and martial law, Mom thought it best to have the baby in the capitalist world.

Soon, the young Loy-Wilson's childhood assumed the character of a tour of the current (and soon, former) sites of socialist rule. Her parents moved to the Soviet capital in 1988 for what turned out to be a five-year posting, and the collapse of Soviet Communism formed the background noise to Sophie's early school years. Images of Boris Yeltsin clambering up tanks and the Russian White House burning, less so youth league football, formed the "stock images" to her childhood.

By 1995, the family had moved again, this time to Beijing. This time, Loy-Wilson came with stock images in her own head: "the Karate Kid, Yamcha (the protagonist of animated series Dragon Ball Z), and dim sum." Hence, she was in for a shock when she arrived in a smoggy industrial capital that, Deng Xiaoping's economic reforms notwithstanding, was still very much a Stalinist city and with a population still shell-shocked after the Tiananmen Square massacres of 1989.

"I had no framework for how to interpret the place," explains Loy-Wilson, and in some sense, she argues, her academic journey can be seen as a quest to assimilate the frameworks to understand the China that she landed in as a teenager. But said quest goes deeper. Walking the streets as a white Anglophone woman, she was frequently mistaken for a Briton or an American–the former bad due to the colonial legacy, the latter arguably worse at the time due to American bombings of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade. Hostility to foreigners and xenophobia is of course not a monopoly of mainland Chinese society, but what struck Loy-Wilson was the tone of the sharp questions she received: China as an anti-imperial country that felt, in spite of its growing economic clout, historically disrespected and subordinated to Anglo-American domination.

Questions, questions … and more were to come. Around the dinner table (itself one of many inside the Australian Embassy compound), Loy-Wilson had discussions with her parents about their relationship with purportedly socialist societies like the Soviet Union they had seen crumble and the People's Republic of China that was, for the moment, their home. Loy-Wilson's parents had belonged to the countercultural movement of the Australian 1970s, a moment parts of which indulged in an uncritical attitude towards Soviet socialism and Maoism. When Loy-Wilson's father studied abroad at Moscow State University in the 1970s, arriving as an enthusiast, he was brutally disappointed by the actual state of Soviet society and the brutal legacy of Stalin's dictatorship. Still, however jaded the experience made him, it also reminded him, his wife, and their daughter of the importance of history as a lodestar to explain the past. A sense of Australian patriotism and a desire for social justice had to be wedded to a realism whose seed would be not cynicism, but history.

Whether in spite of or because of the pageantry of Australian-ness at the Embassy (think sales of Foster's beer), for her final year of schooling, Loy-Wilson returned "home" to Australia, where she began to wrestle with what became one of the pivotal professional and personal decisions that would guide her coming trajectory: to learn Chinese and engage that part of her own (and her country's) trajectory more, or find a new start elsewhere?

During her undergraduate studies for her Bachelor of Arts degree at the Australian National University and the University of Sydney, she wisely chose to dive into intensive study of the language at a time when two very different sets of Australians were growing more interested in the country's involvement in East Asia. Firstly, Australian political and business élites were increasingly desirous of investment and trade in the People's Republic. Residual economic ties within the Commonwealth still mattered, but for a resource-rich country relatively close to the world's growing economies, ties with China, Japan, and Southeast Asia would have to assume priority.

Secondly, however, and more subtly, the study of Australian history in an international context had undergone major changes by the time that Loy-Wilson was growing more interested in history. A pioneering generation of historians of the Chinese-Australian experience had shed much-needed light on the experience of Chinese-Australians, helping to dismantle the myth of Australia as a white nation, or as a predominantly rugged, Outback, frontier society. Much of this literature, however, had more the character of polemics than scholarship (perhaps rightly so–Australia remains the only settler society not to apologize to its Chinese-X population for racial poll taxes). The primary focus was on criticizing the Australian state, but that stress could sometimes give the impression of an omnipresent racial bogeyman opposed to Chinese just because, instead of empirically breaking down the roots of white racism against the "yellow" Chinese (think anxieties over labor market competition).

But there was also a need to emphasize Chinese-Australians as intellectuals and activists in their own right, not just the passive victim of omnipresent white-on-Chinese racism. Correspondingly, Loy-Wilson's first archival based project, which she completed during her Honour's year in the Department of History at the University of Sydney, explored the legacy of William Liu, a Chinese-Australian activist who presented a panoply of arguments against Australian immigration and civil rights restrictions on Chinese-Australians. While Liu remained ignored in his own time, the way he framed his arguments surprised Wilson. While opposed to race as an analytical category in its own right, Liu (writing at the time of the Great Depression) stressed that Australia had a certain humanitarian responsibility to trade more intensively with Asia. At the time, Australia was a Dominion with very limited room for independent foreign policy until 1928 and had to trade almost exclusively through British agents when it came to East Asian treaty ports. But Liu argued that this position, more than reinforcing racist elements within Australian society at large, was creating a double humanitarian catastrophe for both impoverished Australians as well as for starving Chinese.

Loy-Wilson felt she was on to something. Here was a story of Chinese-Australian relations very different from the one she had been told. Indeed, circa the mid-2000s, the story within Australian society apropos China often assumed one of two master narratives. The first, championed by the Australian right, spoke in terms of a menacing Middle Kingdom "painting the outback red" through rapacious and corrupt land deals. Lines like these got huge applause from voters for the Nationals, but what Loy-Wilson was reading in the archives told a more complicated story of exchange in both directions. The second narrative, more typical among respectable liberal society than rough-riders, was of a visionary Australian opening to China in 1972 that spearheaded a new dawn of Australian-Chinese relations. But favored as this narrative might be by political and business élites, it, too, ignored the reality of nineteenth century trade, as well as the less easily marketable story of Australian grain feeding China during and after the cataclysm of the Great Leap Forward. (JFK kindly requested that Canberra cut grain supplies so as to pressure Beijing on Vietnam.)

Her confrontation with questions and contradictions like these drove Loy-Wilson to the research that, after many years of hard work and editing, now forms her upcoming book, drawn from her PhD thesis, Sandalwood Empire: Commerce and Colonialism in Australia and China (appearing with Routledge later this year). Based on work in Chinese and Australian archives–especially those of businesses–she aims to show "how face-to-face commercial interactions helped construct networks of contact and interaction that emerged between Australia and China in the interwar years." The point, she stresses, is not to pursue business and economic history to the exclusion of traditional political history or a transcultural, but rather to show that these latter two domains were inherently constructed by worlds of business, infrastructure, and finance.

Working in the same spirit as historians like Valeska Huber, she shows how a Chinese-Australian world grew upon the "mobility of steam" and ships that ran cargo, mail and supplies between Canton, Sydney, Melbourne, and ports of call in between. The book, then, traces how these sinews and the political and cultural meaning invested in them changed over time. In the book, for example, we find ourselves embedded in the trade worlds of Australian sandalwood, which went on to an afterlife in Chinese incense sticks. Before being processed, however, Australian sandalwood often had to travel under the inspection–and sometimes anti-Australian chauvinism–of British trade agents in Chinese ports. When it did get through, moreover, the emerging trans-Pacific consciousness of some Chinese traders meant that they were aware of Australian discrimination against Chinese-Australians in "white" Australia itself; sometimes, such traders refused to accept Australian goods as "unclean" or "tainted" in an act of intra-diasporic solidarity with their countrymen thrown into a white man's world.

Indeed, as this discussion suggests, Loy-Wilson has written a work that's more than just dusty reconstruction of trade and corporate archives. The point is not just to write business or economic history, but rather to explore the possibilities for the Chinese, Australian, and Chinese-Australian self that such networks of connectivity made possibility. Take gender, for example. As Sophie notes, the Pacific gold rush and the movement of coolies to places like California and Australia was mostly a male phenomenon: at some point in the late 19th century, there were thousands of Chinese men in Australia compared to at best double-digit figures for Chinese women. Arguably, imaginaries of the stolid, paternalistic, Australian frontier family formed a dark filter through which images of the Chinese as unreliable, vagrant, and transient could be projected on Chinese immigrants. (Never mind that many of them may have been supporting transnational households back home in the Pearl River Delta.)

But by the twentieth century, the images and role models on both sides of the encounter were changing. Soon, Loy-Wilson notes, there were many educated Chinese-American women populating Australian cities, who often spoke only English and employed "white" Australian servants to staff and run their households. Overseas in China, meanwhile, Australian representations and, later, Embassies and Consulates, created their own half-domestic, half-professional spheres of dinner meetings, cross-Embassy get-togethers, and the like. The broader point is to stress the long history of blurred spaces–"Chinese" and "Australian," "white" and "Asian," domestic and foreign. The patterns were perhaps most visible at the two end-nodes of loy-Wilson's sandalwood empire, namely the southern Chinese and Australian metropoles in which so much business was headquartered. But like a fractal, these spaces of interaction replicated themselves on smaller scales elsewhere throughout the way-stations of the Pacific–Fiji, Port Moresby, Taipei, Yokohama. Seen from this point of view, the anxieties and hopes invested into today's relationship between Canberra and Beijing mark a continuity, not an apocalyptic turning point or novel reinvention (as the right-wing and establishment narratives might have it).

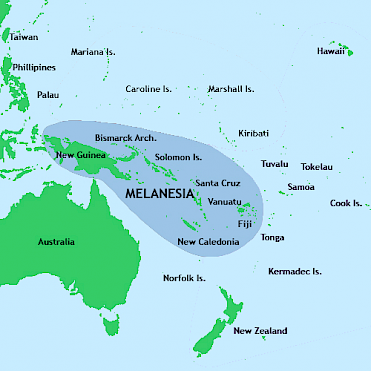

Reflections like these are what motivate Loy-Wilson's second and ongoing book project, prospectively titled Graves in the Forest. She wants to write a comparative study of Australian and (as the narrative moves towards the present day) Chinese developmental practices in Melanesia (Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea). While working on Sandalwood Empire, she explains, she kept on coming across both newspaper materials and colleagues who hinted at a world of development in this sub-region that area studies optics served poorly. Mega-diverse New Guinea was an Australian-run League of Nations Mandate in the interwar period, while after a brief Japanese occupation it was merged with British Papua into a United Nations Trust Territory and external territory of Australia. Since 1975, it has been an independent country, but the rugged terrain made it difficult to extract a potential bonanza of raw materials (copper, gold, and oil). In any event, Loy-Wilson kept on coming across Australians who had either worked in the Trust Territory or on the island after independence–most recently as election observers. Reading the Chinese-language press, however, she saw that China was plowing millions of yuan into development projects in the country, too–portraying itself, of course, in the language of anti-imperialism.

Graves in the Forest aims, then, to untangle the entangled Chinese-Australian history of development using the unusual arena of not just Papua New Guinea, but the other islands in Melanesia (several others of which have histories that do not fit neatly to the usual image of European overseas decolonization centered around the 1960s and 1970s). Perhaps similarly to the work of Stanford historian JP Daughton, Loy-Wilson aims to explore how Australian humanitarian and development efforts often intersected with mass starvation and famine in the island world of Melanesia.

The payoff, then, is not just to add the Australian or the Chinese view to the global history of development, but also to show how the dark pages of Australian history are not just confined to the Outback. Canberra may have lacked for its King Leopold equivalent, but by de-centering the view of Australian national history, Loy-Wilson, her compatriots, and the world might grow more aware of the moral and humanitarian debts involved with the history of settler society down under. The fact that this world of Australian ambitions and projects–often with unintended consequences–receives limited coverage in the media only underscores the need for its historical reconstruction.

We close the interview by asking Loy-Wilson what books she has on her nightstand–what works have inspired her lately? At the moment, she notes, she is making her way through two books: firstly, Moon-Ho Jung's Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation. Similarly to Loy-Wilson's own work, it aims to add a corrective to typical narratives of the Chinese overseas diaspora and settler society. In the book, Jung explores the little-known history of Chinese coolies who ended up in the American Deep South as sugar harvesters, in the process complicating racial boundaries between "black" and "white" society. Jung's monograph, Loy-Wilson notes that she has been making her way through Imperial Debris: On Ruins and Ruination, an edited volume assembled by Ann Laura Stoler.

But beyond these two books currently on her reading list, she cites the works of Australian anthropologist Inga Clendinnen as inspirational for her work. Clendinnen's work on Aztec society, The Cost of Courage in Aztec Society, showed her what history or anthropology at its best can be. "After reading Clendinnen's work," jokes Sophie, "you feel ready to lie down on a stone tablet yourself and have a priest rip out your heart." It might sound grim, but her point is serious: good history involves not just patient empirical re-assemblage of the past, but also the reconstruction of a moral and sentimental universe in which one's subjects lived.

•

Our interview with Loy-Wilson has taken us through the many worlds of the western and southwestern Pacific: from the Cantonese world of China's southern ports, to the way-stations along the way, to the Australia whose history no longer seems easily containable by the shores of the continent itself. Given her presence at Sydney's Laureate Research Program along with Professor Glenda Sluga and Philippa Hetherington (interviewed by TPF earlier this year), it's no wonder that this outpost down under constitutes one of the most exciting nodes in the world of global history institutions. We thank her for her participation in the interview, and we know that we are not alone in following the progress of her work in the future.