Archival Reflections—Spanish Manila’s seventeenth century Media Anata: A quantitative dataset for global histories from below

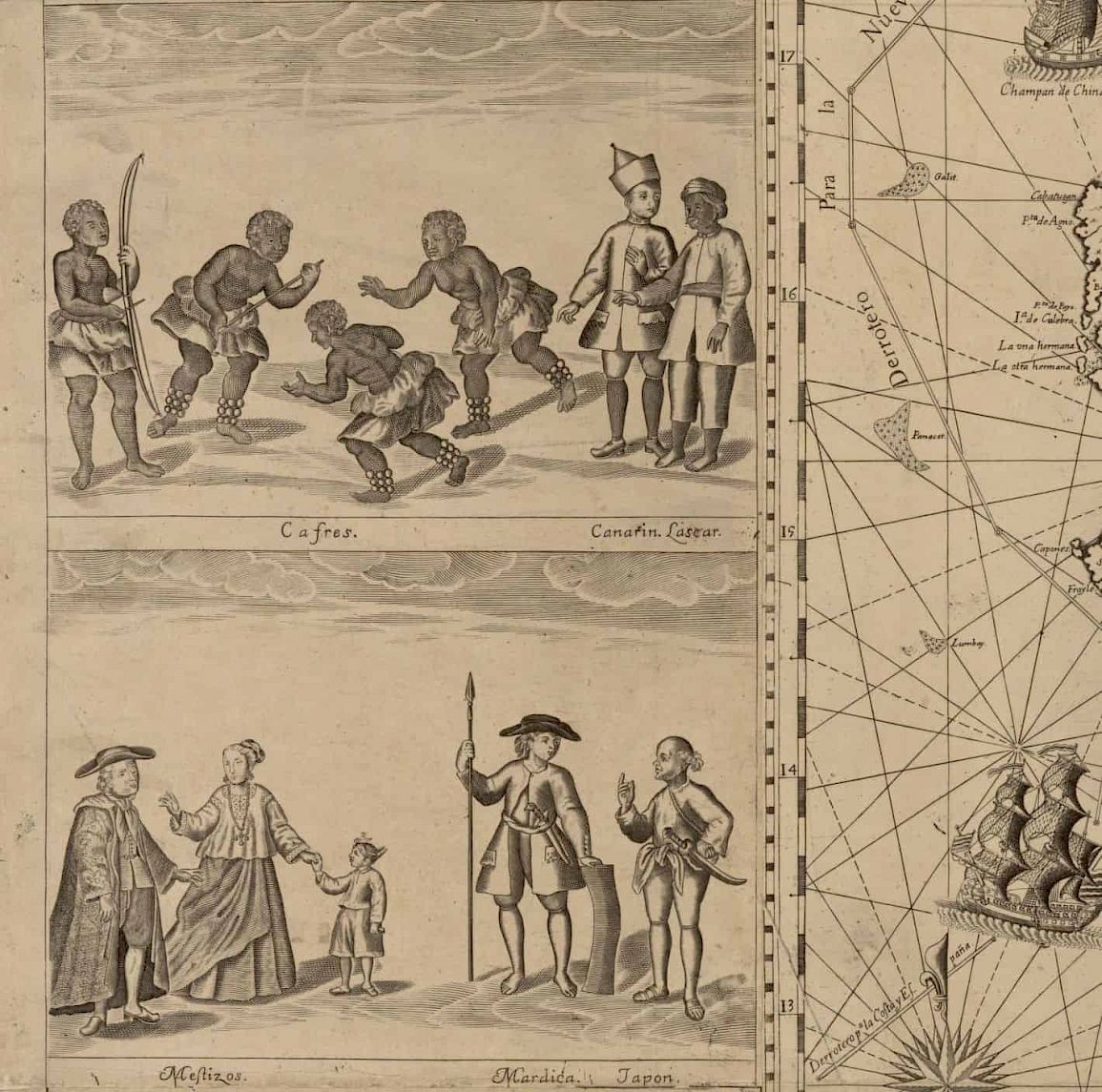

Source: Murillo 1734

By Nicholas Michael C. Sy

“En d[ic]ho dia Doze de henero de mill y seiscientos Y cinq[uen]ta Y seis a[ño]s dos p[es]os de oro comm[u]n que Getrudes de la Concepcion morena cafra libre metio en la R[ea]l caja por la media anatta de una tienda que tiene en esta ciu[da]d por quanto en la vissita que se hizo de tienda no consto averla pagado ni sacado Licencia de govierno que es lo que declaro el s[eño]r juez pribativo deeste derecho dever pagar por d[ic]ha Razon. Consto del decreto que sele bolvio como p[art]e de partida del Lib[r]o comm[u]n y general de la d[ic]ha R[ea]l caxa del a[ñ]o citado” (AGI 1654–6, italics my own; img: Murillo 1734)

The above is a snippet from the register of Media Anata payments made in Manila in 1656. The media anata was a fee imposed on the Spanish nobility during the reign of Felipe IV. Recipients of the king’s grants were charged half (media) of one year of their grant’s income (anata). This revenue funded the king’s court and his wars. The fee’s imposition also allowed the king to assert his sovereignty over the nobility—the latter had to pay up before receiving their titles (Felices de la Fuente 2013, 412–413). However, the entry I transcribed above did not take place in Spain. Nor was its fee charged to nobility.

The empire’s leyes de indias applied the media anata to colonial grants. In Manila, these grants ranged from the privileges of running a shop or carrying a sword, to the privileges of holding municipal office or travelling to mainland Southeast Asia. Manila’s Royal contador (fiscal officer or, simply, accountant) compiled a yearly register of these payments and sent them to the colony’s Real Hacienda. Every register contained several hundred entries. The registry of 1656 had 326 entries. That of 1654 had 362 entries. Each entry had the following components: date, amount paid, grantee’s name, grant given, and terms of payment. Various data appeared less regularly such as: a guarantor’s name, or the grantee’s occupation, ethnicity, or place of origin. Each of these items represents a potential variable for quantitative study. In addition, a tally of payments was recorded in roman numerals at the end of every page, and an overall summation of these tallies was done at the end of every year (AGI 1654–6).

Source: Murillo 1734

The existing literature has used this dataset (i) to qualitatively trace the lives of particular historical subjects and the scope of particular offices as well as (ii) to quantitatively to evaluate imperial finances (Concepcion 2015; Santiago 1990; Alonso 2009). Most importantly, given our interest in global history, historians have started to use this dataset to detect otherwise invisible global actors circulating around early modern Asia. Yayoi Kawamura (2019; see also Seijas 2014, 143–174), for instance, uses the media anata to argue that Japanese Christians entering Manila at the end of the Namban period settled in a far broader area around the colonial capital than previously expected.

This historiography is thin on the ground, but it holds the potential not only to reinforce our understanding of the Spanish Empire’s links with East Asia, but also to intertwine this historiography with the historiographies of Africa and South Asia. In March and April of 1654 sixteen people paid for the privilege of running shops in the colony: nine were Chinese Christians, one was Japanese, one was a “natural” (likely an indigenous Filipino), three were morenos libres, one was from “la yndia,” and one was from Bengal (AGI 1654–6). Seville’s Archivo General de Indias contains Philippine media anatas from the 1630s at least until the 1780s, which potentially allows for a nuanced quantitative comparison of these linkages over time.

There are many pitfalls to the quantitative use of the media anata. Who exactly ended up on these registers? Did the criteria for their inclusion into its denominator change over time? It is as yet unclear what occupations were, at different times, required to pay this fee. The possibility exists that figures for an occupation may suddenly drop (a) because the crown no longer charged it a fee, rather than (b) because people no longer held that occupation. At the same time, the Philippine colony’s seventeenth century influence expanded only in fits and starts. Registration could only be enforced within that scope. Any quantitative analysis will not only have to map that coverage but also acknowledge the existence of an uncountable population in the archipelago who traded, carried swords, held positions of leadership, and sailed to Southeast Asia under authorities—including indigenous authorities—other than Spanish Manila.

These are of course the standard cautions one must take when approaching any historical time series. These datasets tend to reflect the haphazard registration processes that created them as much as the early modern realities that scholars want to study. These challenges make analysis difficult but they do not make it less rewarding. As a quantitative dataset, the media anata does more than confirm what we already know—that multiple non-state actors, and not just elites, interlinked the early modern world. It allows us to measure the magnitude of this reality over time to detect not only moments of growth but also interruptions and reversals.

Note

I thank my undergraduate assistants Ariana Vergara, Bernadette Gamo, Bridget Bico, and Jon Bono Ealdama who continue to assist me in encoding these registers.

References

Alonso Álvarez, Luis. 2009. El costo del imperio asiático: La formación colonial de las islas Filipinas bajo dominio español, 1565–1800. La Coruña, España: Universidade da Coruña; Mexico: Instituto Mora.

Archivo General de Indias (AGI). 1654–1656. Contaduria, Papeles de las Cajas Reales de las islas Filipinas, Legajo 1231–1232.

Concepcion, Grace Liza Y. 2014–2015. Collaborative production of “civilizing spaces” in Spanish Philippines: The Longos-Paete land dispute in Laguna in the seventeenth to eighteenth centuries. Synergeia 5: 23–43.

Kawamura, Yayoi. 2019. Llegada de productos japoneses a Manila en la fase final del periodo Namban. Mirai: Estudios Japoneses. 3: 45–58.

Felices de la Fuente, Maria del Mar. 2013. Recompensar servicios con honores: El crecimiento de la nobleza tutilada en los reinados de Felipe IV y Carlos II. Studia Historica: Historia Moderna 35: 409–435.

Murillo Velarde, Pedro, S.J. 1734. Carta hydrographica y chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas : dedicada al Rey Nuestro Señor por el Mariscal d. Campo D. Fernando Valdes Tamon Cavallo del Orden de Santiago de Govor. Y Capn [Map]. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013585226/, accessed 02 April 2020.

Santiago, Luciano PR. 1990. The Filipino Indios Encomenderos (ca. 1620-1711). Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 18(3): 162–184.

Seijas, Tatiana. 2014. Asian slaves in colonial Mexico: From Chinos to Indians. New York: Cambridge University Press.