Human Rights and the Global South: A Conversation with Steven L. B. Jensen

Human rights are facing perhaps their greatest challenge yet. After a failed military coup in July last year, Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has led a purge of the country's central institutions. A much-contested referendum in April only expanded Erdoğan's stranglehold on the government. Over a similar timeframe, Erdoğan's Filipino counterpart, Rodrigo Duterte, has spearheaded a devastatingly brutal antidrug campaign, sanctioning the extra-judicial killing of thousands of suspected drug users and sellers. In Egypt, President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has imprisoned members of the political opposition, arrested human rights activists, and outlawed many aid organizations. Meanwhile, the United States—traditionally considered human right's earliest and greatest champion—has seen the election of President Donald Trump. According to a tally compiled by Amnesty International, in just one hundred days in office, Trump threatened human rights in at least as many ways.

Viewed from today's perspective, it might seem like it's only recently that the US has ceded global leadership on human rights. But, as Dr. Steven L. B. Jensen shows in his book The Making of International Human Rights: The 1960s, Decolonization, and the Reconstruction of Global Values (2016), the history of human rights was never simply a story of American or Western hegemony. Moving the locus of study to Jamaica, Ghana, the Philippines, Liberia and beyond, Jensen argues that human rights were as shaped from within the Global South as they were from without. In Jensen's words, actors from the Global South "gave a master class in international human rights diplomacy to both the Eastern and the Western actors."

Many scholars struggle to connect with non-academic audiences. In his work and in his writings, Jensen straddles the border between academia and international policymaking with comparative ease. Currently a researcher at the Danish Institute for Human Rights, Jensen is the author and editor of multiple books and articles. Prior to completing his PhD at the University of Copenhagen, he worked in international development: first at the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs' Department of Southern Africa, and later for the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) in Geneva. His PhD thesis was published as The Making of International Human Rights last year. Since then, he's been on something of a roll. Most recently, his book received the Human Rights Best Book Award and the Chadwick Alger Prize for the best book on international organization from the International Studies Association.

The Toynbee Prize Foundation was lucky enough to chat with Jensen during a recent visit to Cambridge, Massachusetts. Jensen was in town to attend a workshop on socioeconomic rights convened by Professors Samuel Moyn and Charles Walton at Harvard Law School. Jensen spoke about human rights' origins in the Global South, how exactly he came to be known as the "Jamaica guy," and what the future holds for human rights scholarship.

–Aden Knaap

INTERVIEWER

These interviews usually end with a question like, what's next for you? Given you're in town to discuss your current research, I thought it might be interesting to start with that. What are you working on at the moment?

STEVEN JENSEN

The project I'm working on right now is a history of economic and social rights after 1945, and how they entered the international human rights framework and shaped wider global politics. It's very much attempting to find ways to reposition the normative dimension—which is always there in human rights research—by finding creative ways of working around it. I'm interested in getting a sense of the political processes and the messiness of history that shaped the role and significance of economic and social rights in a broader international context. There is a much wider story, well beyond the traditional narratives of civil and political rights versus economic and social rights that has been fitted too neatly into the Cold War East-West framework. I'm trying to track these dynamics and find different processes and historical trajectories.

I'm also thinking a lot about the geographies of human rights. I want to really explore this and take it in surprising directions—outside the North or the West—to look at the intersections of South-North and South-East. My focus on economic and social rights is not merely about redistribution, since I think social and economic rights work in a whole range of ways. Of course, redistribution is one element, but my research is also bringing me into writing histories of discrimination, and looking at national development planning in colonial settings toward the end of empire. Social and economic rights have also underpinned democratizing trends in the post-1945 world as well as served as critical enablers for the work to promote and protect civil and political rights. So there are a whole range of issues that pop up. It's also about tracking the integration of human rights and development at an earlier stage than what's commonly understood. In a sense, it's a process of getting lost. Sometimes you have strong research questions—and I do have that—but I'm also just letting myself be led astray, because I think we need to find new ways of narrating these histories. It's not about filling out gaps; it's taking elements that have not been fully explored. And from what I'm finding, there's a solid base for following these uncertain paths. It's these historical trajectories that I'm interested in, and that I think can be illuminating for a range of other fields and topics of global history as well as national histories. Of course, the new research also builds on my previous work in my first book, and on now having a solid foundation in the human rights historiography.

I think the history of social and economic rights is one of the new frontiers in the whole field of human rights research itself. There is a significant amount of current research on social and economic rights in places like South Africa, India, Latin America, but it has a very presentist-oriented take.

INTERVIEWER

I imagine if you're really interested in avoiding such a presentist framing, then the periodization of this second project will be really crucial?

JENSEN

Absolutely. Because I do find that some of the contemporary research on social and economic rights is too narrow, focusing on the justiciability of these rights and their constitutional usages in the contemporary era. Of course, some of that research is inspiring for me. But as a historian, I want to look at broader historical transformations, and I think that body of literature would really benefit from being historicized.

One aspect that will be really fundamental or foundational to this work is taking that historical space from after the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) up until 1970—a period that is, in so many ways, the "black box" of contemporary human rights history—and exploring that more fully. The link between human rights and decolonization is still underexplored. It is not just a story of global transformation but also a historical space—one that we as historians should try more creatively to inhabit and explore. I've done some work on this nexus between human rights and decolonization, and Roland Burke and Fabian Klose have done some work, but there's still lots to capture there. I'm very inspired by Susan Pedersen's way of thinking about the change that happened in the international system of states: from a hierarchical empire-based system that, over some years, became this semi-functional system of sovereign states—in other words, in formal terms, a more equal system. That historical transformation fits very well, I think, with the 1950s and '60s. Now that's a transformation of states. Look at Frederick Cooper. He makes a very fine observation when he writes about social rights and the end of empire, and talks about the rights-claiming colonial subjects in the 1940s, who by the 1960s enter onto the world stage as a new category, namely the poor of the world. I think linking the state perspective in Pedersen's argument with the more people-oriented one that Cooper captures makes sense when you're a human rights historian thinking about this historical space.

But I also want to look at how that has influenced later developments: that is, through the '70s and '80s and potentially into the '90s. That's because a number of the processes I've captured will, of course, have failed or proven the shortcomings of the human rights approach. However, I'm also interested in the legacies and subtle impacts that these processes from the past still have today. It is not an either-or—it is a lot more interesting than that. I'm not trying to document the rise and rise of human rights, the perfecting of it. There are many flaws and disruptions in the history of human rights because these are deeply contested and contingent political issues. But at the same time, there are these subtle impacts that I think can illuminate the way we work with later periods by understanding where some of these issues came from. In the final chapter of my book I use a metaphor of a cabinet full of glasses to represent the history of human rights in the twentieth century, explaining that some glasses are "half full, some half empty, some drained dry and some filled to the top; for some, the contents have fizzled out and, for others, they are boiling; and then there are those glasses smashed beyond repair." It is this plurality and, hopefully, finer granularity that I am also trying to capture in my historical work on social and economic rights.

So that's why I'm not just jumping to the '70s. That's a difference in my approach that hopefully has informed the field, I think, and added complexity to our understanding.

INTERVIEWER

One way of introducing that complexity is through your choice of periodization. Another is through your choice of geographies. What will the choice of geographies be like for this next project, and how are you going about selecting them?

JENSEN

Again, I use the United Nations as a setting to start from, because it is not a closed ecology; it's a very dynamic one. It's also a good entry point for looking at transnational and global links. So the UN still informs the type of geographies that I'm looking at. And, much to my enjoyment, I'm ending up with Jamaica again. Because Jamaica had a really refined way of working with human rights in the 1950s in national development planning. It's about the way that human rights come to sit within economic planning in Jamaica and looking at planning in a democratic society. Jamaica was pushing the planning agenda, but with a very explicit anti-Soviet philosophy of what state planning entailed. And there's a very refined articulation that's linked to the rise of development economics because one of the key actors in this political and intellectual network is Arthur W. Lewis, who's often credited as one of the shapers of development economics as a research field. So, in a sense, through this project I can also look at the multi-faceted domestic background for Jamaica's global leadership in human rights in the 1960s, which was partly the subject of my first book.

INTERVIEWER

So in that sense it's a prequel to The Making of International Human Rights?

JENSEN

Partly. I've found incredibly rich material by being back in the archives in Jamaica, so that's one of the things I'm working on. And then as I'm moving back into the '60s, I'm looking at the framings of human rights and international development policy, because while we know more and more about the processes of trade and development—which featured a very economically or technically oriented framing of what development meant—there is this parallel process going on of broader thinking in terms of social development and human rights. I haven't looked in detail at that, but that will emerge along with some new geographies related to the rise of international development. It will also reveal something about the power relations in defining international public policy as it was other approaches that came to dominate international development policy over the next few decades. Again, the UN is an interesting setting for seeing when these issues get traction, and then working out how you can then capture the type of policy responses that occurred within and outside that system. I think the field of human rights history is really opening up—it is by no means a self-contained field of study.

INTERVIEWER

Histories of development are really opening up, too, I think. Scholars like Daniel Immerwahr (who was previously interviewed on the Global History Forum) are working to flip the orthodox narrative of development: from a story of modernization theory in America looking outwards, to looking instead at how non-Western historical actors engaged with ideas of development.

JENSEN

I got a question on this yesterday when I was presenting, in fact. I cited one of the economic advisors linked to Norman Manley's Jamaican government, who was reviewing American economist Walt Rostow's book, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto in 1960. He predicted how much damage this book was going to do by, among other things, "encouraging complacency in the wrong quarters" and the "great disservice" the book was about to do on a cause Rostow no doubt "sincerely cherished." So there's a whole different universe of this field of economics to uncover and contextualize. And, of course, many people are familiar with Arthur W. Lewis, but there's still more to discover about the political milieus of Caribbean political and economic thought. And that's just one track. I'm also interested in exploring some new geographies, I'm just not sure specifically where: it could be Ghana, it could be elsewhere, I don't know yet. But I think this approach in human rights scholarship of working with Cold War Third World archives continues to be very promising.

INTERVIEWER

Speaking of those archives, I want to turn to the focus on the Third World in your first book. In your review of Dr. Samuel Moyn's Christian Human Rights (2015), you're very clear in wanting to look at how human rights have purchase in the Global South, that this isn't a wholly Western narrative. How did you come up with that framing of the Third Word's impact on human rights for your first book?

JENSEN

My original Ph.D. proposal dealt with human rights, but it was pretty boring looking back. I had no idea that there was this very strong Global South framing for human rights, so I didn't go looking for it. The original project was about trans-Atlantic dialogues on human rights, European and Americans. I had made 1968 the starting point. I had actually written a book in Denmark about 1968.

INTERVIEWER

So you're Denmark's expert on 1968?

JENSEN

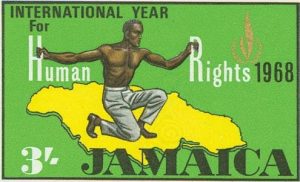

In a Danish context, it is fair to say I'm one of the leading experts! I've also published one or two things internationally on that. I was struck by a paradox: that I had read so much about 1968 to the extent that I had published a book on it, and yet I had no clue that '68 was the UN International Human Rights Year. I couldn't understand how there was nothing in the literature on 1968 that had made that connection, let alone a reference. And when I looked back I found only one, in historian-journalist Mark Kurlansky's 1968: The Year That Rocked the World (2004). So I thought I'd begin from that starting point: going back to 1968 and looking at these trans-Atlantic dialogues. But when I went to the UN archives in Geneva something else quickly emerged: there was a different dynamic, what I interpreted as a strong '60s framing for human rights. Then, when I was two months and ten days old as a PhD candidate, I went to a seminar in Freiburg in 2010 that Samuel Moyn and Jan Eckel [who has also spoken about this same conference on the Global History Forum] organized. The seminar had quite a profound influence on my approach. I was struck that there were about thirty historians there pretty much agreeing that it was in the 1970s that human rights took off. Even though I'd only worked on this for two months, I was enmeshed enough in these sources to say well, if everyone else is doing the '70s, then I'm just going to veer off into the '60s. And then Jamaica suddenly popped up.

INTERVIEWER

Of course! Since, as you explain in your book, it was Jamaica's representative to the UN, Egerton Richardson, who pushed for the UN to name 1968 the International Year for Human Rights.

JENSEN

Exactly. In the beginning, I ignored Jamaica, thinking this was really interesting but it was not my project. And then suddenly something lit up and I thought this has to be an angle. And then I pursued that and it opened up more and more perspectives. So I was lucky that early on in my process a new PhD project emerged, which was much more interesting than the one I had set out with. So in a sense I just let myself be guided by the sources. And because I was working with something that was not captured by pre-existing research—I mean Roland Burke looks at some of this but I was looking at very different processes to the ones he was looking at—I eventually needed to do extensive archival work in ten different countries. There were so many things that needed to be mapped out and then validated. It took some work making the historical connections I wanted to make as solid as possible. For example, making the point that the rather well-studied Helsinki process and the human rights coming out of that actually had important roots in Global South diplomacy in the '60s. So it was about being really open and taking serious the multi-tonality of the UN system and not just dismissing these actors as not being interesting or having no impact.

Then, when I was talking about the new project just four months in, people were suddenly interested in my research. At one point at a conference, Susan Pedersen read my chapter and said you need to go to Jamaica to do archival work and insisted that there would be stuff there. I was lucky enough to get funding from the Oslo Contemporary International History Network so off I went. And that archival work brought that last element of having much greater depth and nuance regarding the voices of Jamaicans themselves. I felt like this kind of archival work across multiple geographies was necessary because it wasn't just about documents—it was about validating my arguments with real depth. It wouldn't be enough to make the argument based on the UN processes because, despite a voluminous record, that would still be a thin source base. I also needed to look at the strategies applied by different countries, and how they linked to other processes. So that was how it evolved. In that sense that Freiburg seminar was really significant for me because I was introduced essentially to the whole field of historians working on human rights, which was obviously an incredible boost for my work—possibly for all of us. But I also realized that there was this niche: that people were concentrating on the '70s and that there was something there in the '60s to look at. I didn't know where exactly I was going with it at that point but I knew it was significant.

And as well, the chapter in the book on religion was again a complete surprise to me; the fact that you have this process of proposing a Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Religion Intolerance [you can read a blog post by Jensen about the Convention], which I think is the most significant attempt in the twentieth century to make religion a subject of international law and had not previously been studied by anyone across all the disciplines involved in human rights research. That surprised me.

INTERVIEWER

And again, I suppose that relates to the presentist framing of much early human rights scholarship.

JENSEN

Yes, because this is a field that very much started with legal scholars, who are mostly interested in conventions or legal documents that created standards from which you can do legal interpretation or base jurisprudence. When you have a failed project that leaves such an unclear or hidden legacy, it's not as interesting to legal scholars. But for historians, failed projects can be really illuminating, if we can document that they were significant and the ways that they were significant. So this project also made me reflect on what we do as historians compared to other disciplines and what it is that we bring in. It was also about taking failures seriously and taking actors that have been excluded seriously.

INTERVIEWER

There's a compelling synchronicity between your book's argument—which upends Cold War distinctions between East and West but also between North and South, and argues against seeing human rights as a story of Western imposition—and how this maps onto its methodology. You insist that we can't just look at the UN archives, we also have to track this process outside the UN system.

JENSEN

It's also about acknowledging the nuance in the agendas of Third World actors. Because I think in the human rights field the Third World has been grouped together too much. It's about bringing out these unique histories. This is not a Third World agenda, but it's an agenda carried forward by a group of states from the Global South. So you get this nuancing or differentiation between them, which I think is an important point. These countries have their own national histories, their own contributions, just like Denmark or other Western countries have.

INTERVIEWER

You've talked about how the source base brought you to this history. What theoretical works aided the framing of your argument? Or did that come later? The book's footnotes reference a great diversity of historical scholarship—E. P. Thompson, Frederick Cooper, Matthew Connelly, to name just a few.

JENSEN

Well that's an interesting question, because I realized that some of the things I had to do with this work was in a very conservative mode of being a historian. I had to go back and really take chronology very seriously. And that was linked also to thinking about agency: who are the actors and what are they shaping, because they really had an impact both on the historical trajectory and also on the contents of the human rights story. So there is in the book a classic kind of revisiting of the chronology, but from the perspective of agency. This was where E. P. Thompson really fitted in for me and this is the process of "making" that I refer to in the book's title. For example, I argue that the human rights dynamics emerging from Helsinki Final Act was not a by-product of détente, a coincidental, unintended consequence, which some scholarship would say. No, it wasn't; it was a process of making. And I felt that E. P. Thompson's framing was very helpful for that.

I guess I was straddling so much that it became a little bit of an eclectic reading process as I tried to bring everything together. And I came back to the historical discipline after having worked for several years in international development more as a practitioner or as an international civil servant, and so discovering more recent works was really inspiring. For example, the type of framing and just the sheer knowledge of Frederick Cooper's work was really beneficial.

I often say, what did I know about Jamaica before I started this? I knew Bob Marley and reggae; I knew the story of really fast sprinters; and I knew that they had a bobsledding team in the Winter Olympics. And that was in some ways all I knew. But what inspired me was that I did have this image from being a kid of having seen television recordings of Marley uniting the hands of two leading but bitterly opposed Jamaican politicians at a big concert in Kingston in the 1970s. And I remember being in the UN Library in Geneva years later and thinking what was this Jamaica thing? With that image of bipartisanship in my head it quickly dawned on me that Jamaica had a two-party system and that was maybe why something had emerged there, since so many other states had become authoritarian, one-party states. But that was literally all I knew about Jamaican history and that first step was mainly my intuition at play. So of course I had to read up and understand and get a full grasp on that. That was just incredibly enjoyable.

As part of my PhD, I was a visiting researcher at Yale Law School and there were real benefits of being both in a law environment and in a history environment. There, I was referred to as the "Jamaica guy," which really became a badge of honor for me. At Yale, I was studying with Paul Kahn. His book The Cultural Study of Law. Reconstructing Legal Scholarship (1999) really helped clarify my methodological approach. His work offered both practical and critical ways of engaging with international law and human rights. Part of what I was doing at this point was gate-crashing law environments and legal scholarship, so that experience was tremendously helpful for me as a historian.

And in terms of Matthew Connelly and others, I think the cross-fertilization of transnational and diplomatic history was very helpful in seeing the ways this was being done, the arguments that were being made. I don't think theory is very strong in the book, but it's these approaches that are both theoretical, conceptual, but are also very practical, which I found useful. I just immersed myself in different forms of historiography that needed to be brought together. I don't write about Bourdieu but his concept of the field was important to the way I was imaging this diplomatic work at the UN. I always had that image of the field and these figures moving around or operating in these political and diplomatic spaces or ecologies. And then there were also a range of new works which I also drew inspiration from as my research developed. As I already mentioned, I heard Susan Pedersen present at a conference on her work for the book The Guardians: The League of Nations and the Crisis of Empire (2016).

But the book that had the most profound effect on me was Danielle McGuire's At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance–A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (2010). My research revolved around the United Nations as a forum reflecting global political trends and then I took some steps, however small, outwards. McGuire's book moves the other way, connecting with and re-discovering the lived realities of the women in the book. She then shows how their experiences were part of a much larger and disturbing story about the United States in the twentieth century. It is just such an impressive piece of scholarship. Her influence is maybe not visible in my book but I can tell you, it is there.

INTERVIEWER

You've alluded to how your time away from academia also shaped the book. How so?

JENSEN

In terms of my background, I studied history at the University of Copenhagen and also had a Master's degree from Edinburgh, and when I finished I asked myself, what should I do next? I thought about going into research, which I had a strong interest in, but I also had interests in other things. I got a job working for the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, working on development in the Department for Southern Africa. And from there I ended up at the UN working at the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). I've worked on HIV/AIDS now for about fifteen years, and I still do some work on that.

Looking back, it has really shaped my approach as a historian, and enabled me to do the things I did with this book. One thing is that I really learned the intricacies of UN work, and the processes: how agendas move, how they get disrupted and picked up again. And that methodology—being able to track sources and knowing how to work those structures—was very helpful. There are two other things that I think were very influential, because during my time working there I witnessed many instances where really constructive and important ideas came from Third World actors, from actors from the Global South, but then at some point somebody else would take credit for them. Let's say there was a certain Western bias to taking those credits. So I noticed that happening in real time. I think it resonated then when I looked at these human rights stories. I was ripe for accepting this refined Jamaican human rights diplomacy in the '60s because it resonated with what I had experienced. It made sense.

The third element here is that I've also seen the HIV/AIDS response grow and develop since 2002 and have seen how vital community organizations and activists were in this: whether it's people living with HIV, people from the LGBT community, or sex workers or drug users. I think they have been the greatest developers of international public policy in the last fifteen years—these key constituencies for the HIV response. And that has been one of the benefits of my work; they have taught me different ways of seeing, and different ways of shaping international policy and diplomacy. That is the other thing that made me receptive to looking at these completely unacknowledged actors and pursuing their trajectories. In that way, I've benefited a lot—methodologically but also in terms of interpretative frameworks. It gave me the courage to veer off at points where I didn't really know where it would take me. My work therefore owes a lot to the people living with HIV, LGBT persons and harm reduction activists—as well as my former UNAIDS colleagues—that I have encountered over the years. I am very pleased to acknowledge this debt of gratitude.

INTERVIEWER

On the theme of international policy, what has been the reaction of the book from within international policy forums (as opposed to academia)?

JENSEN

The reception has been very positive and really motivated me. For the human rights community, it's a really valuable book. It challenges the standard human rights story: the ownership of it and the dynamics around it. I wrote a piece for Open Global Rights last year where I said the human rights community makes claims about universality, but then that movement has gone ahead and presented a discounted version of what that universality story entails. It was a self-critique—I work at a Human Rights Institute, so I included ourselves in having failed in this and made the point that there was a need to acknowledge the forms of exclusion that have existed. And that piece just went viral, which meant it must have struck a chord.

So it's both the academic reception that has been very supportive, but also the human rights community. That's why I had a book launch in Geneva with the Danish and the Jamaican ambassadors. My book enables us to open up discussions that have been really locked down. A large part of UN human rights diplomacy right now is very conflictual and very divisive and finding new ways of speaking about these issues and finding new platforms has been very hard. And the approach in my book has certain potential. So that has been really nice. But there is also an implicit critique about how the human rights movement has managed or nurtured its own history. I've found that they're very receptive toward that critique and have acknowledged it and that this is actually a helpful way to move forward.

And then, of course, there has also been the reception in Jamaica. After the archival work I'd done in Jamaica and after I'd gotten my doctorate in history, I felt that I was obliged to bring this history back to Jamaica. I defended my PhD in early 2014 and then realized that June 2014 was the fiftieth anniversary of the first foreign policy strategy of Jamaica as an independent country, which I think was probably the first strategy of any country that integrated human rights into foreign policy. So I wrote to some people asking whether this was a good occasion to give a talk. Luckily some people mobilized so there was enough of a crowd and I gave a talk at the University of the West Indies. Somebody had brought out people from the Jamaican foreign ministry, including some retired diplomats. I just struck a chord with them since several of them knew the Jamaican ambassador Egerton Richardson, who is a main character in the book. They just said they had no clue that he did this with such profound effect. It was a completely forgotten story.

One of the questions I received was why did this research not take place in the Caribbean? A big part of the answer is I come from a setting that has the resources to do academic work and I've been able to travel with friends helping me out by hosting me in various places. At the outset, researchers at universities in Global South contexts seldom have the resources to undertake this scope of archival research so there's a resource imbalance. But there's also this real interest coming from the Global South. After my talk at the University of West Indies, I was asked to give a lecture at the Jamaican Ministry of Foreign Affairs since they felt they needed to inform the staff in the diplomatic service because this was an important story for them. I went and spoke at the Foreign Ministry in Kingston. What emerged there was a very different sense of ownership due to the story I could present about Jamaica's innovative role, but also because there was an acknowledgment of the real qualities in their diplomatic service, which I think is one of the things that did continue from this 1960s human rights in Jamaica story. I went back again in 2016 and continued some of these conversations. So the book has been picked up and has prompted reflection on the need to do more research into the history of human rights there. That has been the most stimulating reward for me—that I've been able to bring the story back—because I felt obliged to do so and because it's a unique and fascinating history. So I've been very lucky with this receptivity. It shows, I think, why nurturing the historical imagination is important to contemporary debates.

INTERVIEWER

Speaking of contemporary debates, some critics of the book have posed the question, "well, why does this matter?" What is your response to reviewers like Dr. Annette Weinke (published on H-Net Reviews in German) who fault the book for taking what they see as symbolic victories for human rights by Third World actors at face value?

JENSEN

I really appreciate when people engage with my work and I always try to be respectful of that. But I think she was very dismissive of non-Western contributions to human rights. Of course, it's an argument that I'm pushing, but I also think that I document, for example, the impacts on the Helsinki process and the way they influenced Western actors like the US and the UK. I think she left out the subtleties of the impact that diplomacy can have. The way I built the Jamaica story is this arc of them doing this and pursuing these agendas and of course there is a domestic reality that is complicated and they did not achieve the type of social and economic development that they want. But I show how this vision crashes in 1968 with lasting effects. I don't think she fully acknowledges, for example, that the UN in the '60s is incredibly dynamic because it played host to the overlap of the colonial, the anticolonial and the postcolonial. It's this world that was being shaped; historical actors at the time didn't know where it was going but it was very clear to them that innovations are coming. And maybe I was a little bit simplistic in how I discussed other research. Of course, this was the subject of a much more complex discussion in the dissertation, but I took a lot of this out for the book. She also claimed that I was very critical of Israel. And I just can't see where that takes place in the book.

INTERVIEWER

I think her point was that these anticolonial human rights movements were themselves hierarchized, so the exclusion of Israel was one way in which this played out, and that you didn't acknowledge this dynamic fully.

JENSEN

I just can't see where I was critical of Israel. What I try to do is tell this story of religion and how problematic the Six-Day War became in this, but I'm not blaming Israel, I'm telling a story of religion and explaining how a localized or regionalized conflict had these global impacts. I actually presented some of this research at Tel Aviv University in front of a highly informed audience that included the prominent Israeli jurist Natan Lerner and I found the participants to be open and very interested. Of course, they hadn't seen the book. I was just surprised by her critique. The question of Israel is, unfortunately, a very typical divide in the human rights debate that people position themselves on and I tried to navigate that without taking a position. I mean, I don't need to have a position, that's not what this story is about. All her other points are legitimate criticisms to discuss I think but this one was strange. She also said something about the Soviet Union and Portugal. At times, I expect the reader to think for themselves. I didn't need to give grades to each state that I was covering, I felt that would be a little bit too didactic. In a sense, I was trying to avoid that very normative way of judging.

INTERVIEWER

And yet, there is a normative argument being made in your criticism of postcolonial studies in the book.

JENSEN

Yes, if there's something I think I criticize then it's postcolonial studies, which has often driven forward a cultural relativist critique of human rights. What I am saying is, hang on, there is an amnesia at play here, because exactly at the founding moment of your field—namely, the postcolonial moment—these countries were actually pushing human rights. They were doing it based on a vision of equality and non-discrimination—that maybe was not always as individually focused as how we would today think of human rights—but they still promoted them and were foundational to the evolution of the international human rights system. Through human rights, at least in part, they were aspiring for an international system that would work better for securing international justice and for negotiating solutions on a whole range of issues of international concern. So human rights became a vehicle for a vision of equality which was about giving these countries a fair chance. In some ways, my book includes a critique of the postcolonial self-understanding and the ways that some of the actors in these states have been able to disengage too easily from human rights frameworks and obligations when they were influential in shaping them in the first place.

INTERVIEWER

That's an argument that Roland Burke also makes in his book, Decolonization and the Evolution of International Human Rights (2010).

JENSEN

Yes, that's a work that I find very impressive. There are many similarities between how Roland and I have approached certain things. We're actually coming out with a co-written piece on methods in human rights history where we've tried to outline the elements that we believe need to be considered to do this well: namely, being more reflective about the representativeness of our stories and the sources that we consult. We identify a number of existing blind spots that we think need to be part of a wider reflection on the research methods that we use as historians.

There are some works in this field that have been hagiographic and that have elevated certain persons. And, of course, I elevate the Jamaican ambassador. But I do it as a way of saying, well, if we have this actor that's so key, then there must be a whole set of networks and causalities around him. We have to rethink why is it that the Caribbean produces him, what are the intellectual networks, what is his trajectory, and how then is he positioned in the international system that makes this possible, instead of simply having Eleanor Roosevelt as the iconic image of human rights.

INTERVIEWER

What do you see as the future of the human rights field? In that review of Moyn's Christian Human Rights (2015), for example, you talked a lot about how crucial you see the role of religion in challenging the standard human rights narrative.

JENSEN

I think it's such a rich and diverse field now. We're way beyond Samuel Moyn's The Last Utopia (2012) at this point; there are so many others that have contributed to this field. Which also means it's not a Moyn versus Jensen discussion as I have, on occasion, seen; I might be wrong, but that doesn't then mean Moyn is automatically right. So many other scholars have contributed to the field and I think the field is in a healthy condition. I really think that social and economic rights are one of the paths forward, and there are more geographies to come in. There's just been an interesting piece by James Kirby in the International History Review on human rights in Botswana, from the final years of colonialism to the early years of independence during the 1960s and 1970s. Paul Betts and James Mark are running a comprehensive research project where they are aiming to bring the socialist world and its complex but fascinating role into this international story. There's also Cindy Ewing's dissertation work where she is bringing in a wider set of especially Asian actors to the human rights story in the early post-1945 era. Right now, human rights are very popular, and if you propose a panel to a conference on human rights you have a really good chance so there's a certain fashion element which can always entail some risk. I believe, however, that there is ample opportunity to weave human rights history very creatively into other fields. We previously had to simply get the human rights history in place, but now we have so much knowledge that we can move beyond that.

INTERVIEWER

Yes, and I think that's testament to how rapidly the historiography of human rights has developed: that it really has only occurred in the space of the past decade. It's a point Sam Moyn himself made, I think, when he wrote that "the end is nigh" for human rights history.

JENSEN

I'm not so concerned now with the debates around periodization. Of course, Moyn's book placed the beginning of human rights in the 1970s, and in a sense I responded to that, arguing instead for the importance of the 1960s. The PhD the book was based on was actually called "Negotiating Universality: The Making of International Human Rights, 1945-93." But Sam was the series editor and suggested highlighting the 1960s, since that was a unique selling point and there hadn't been much written on it. I think it was both clear-sighted and the most honest thing to do, given the main focus of the book. So, of course, my book is pitched a little to that decade argument. There's still more to do, especially with the 1950s. But that's not the way we should guide research.

Human rights history has been really historicized in the past few years because we no longer have these long teleological explanations. So it's more about focusing on these alternative geographies, and being really creative and inventive in how we bring these in. And that's what's really exciting because we can bring in new regions, new countries, new sets of actors while at the same time shed new light on the Western world as, for example, Mark Philip Bradley has done in The World Reimagined. Americans and Human Rights in the Twentieth Century (2016). Bringing in more scholars who are themselves from the Global South would be a huge contribution. As part of my work at the Human Rights Institute, I have taught human rights practitioners from various African countries and for them this is ripe—suddenly they're at the center of the story. I remember one course participant saying, "we have all these stories, our own stories, but who listens to us?" These words still ring in my head to this day. Another course participant said he had done a Masters-degree in Human Rights, and what they got were these Western textbooks that also covered the historical evolution and all the teaching was based on that. That is simply not good enough.

These are going to be really complicated histories where human rights will be exposed for all their shortcomings and faults but maybe also gain renewed relevance. But that is part of the human rights history and that duality should be captured. I think human rights are linked much more to histories of state formation in the mid-twentieth century than we have been able to capture so far. So the black box of human rights history still has plenty to reveal!