Thinking Through Water: An Interview with Sunil S. Amrith

“The history of water,” writes Sunil S. Amrith, “shows that nature has never truly been conquered.” Nature is a dynamic presence in Amrith’s oeuvre. As a historian of South and Southeast Asia, his research engages the spaces, movements, and processes of a uniquely Indian Oceanic region. The worlds recounted by Amrith are often ones marked by the ambitions of empires and polities, the mass migration of human labour, and indeed, the furies of nature itself.

In his latest book, Unruly Waters, Amrith shows how “the schemes of empire builders, the visions of freedom fighters, the designs of engineers—and the cumulative, dispersed actions of hundreds of millions of people across generations—have transformed Asia’s waters over the past two hundred years.” It testifies to the dreams that societies have often pinned to water, as well as its unwieldy and turbulent nature. In his account of “the struggle for water” and control over the Asian monsoon, we come to understand how climate change exacerbates a problem both already in-progress and connected to histories of “reckless development and galloping inequality.”

Sunil S. Amrith is presently the Mehra Family Professor of South Asian History at Harvard University. He was the 2017 recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship. From July 2020, Amrith will be the Dhawan Professor of History at Yale University. His most recent book publications include: Unruly Waters: How Rains, Rivers, Coasts, and Seas Have Shaped Asia's History (Basic Books and Penguin UK, 2018), Crossing the Bay of Bengal: The Furies of Nature and the Fortunes of Migrants (Harvard University Press, 2013), and Migration and Diaspora in Modern Asia (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

In this conversation, we discuss the role of water, nature, and inequality vis-à-vis history; the fields of global and environmental history; and lastly, some of the thoughts and practices that underlay the historian’s craft.

—Mahdi Chowdhury

Water is a recurring question and theatre of history in your work (be it in the form of oceans, rivers, rain systems, dams, or coasts, etc.). What can we learn about the past through this perspective?

I think I was initially drawn to oceanic history for the same reason that so many of us have been, which is to say that focusing on bodies of water allows us to think about the deep interconnectedness of societies that have tended to be studied separately. My entry-point into oceanic history was very much from that moment, about ten to fifteen years ago, when the boundaries of area studies were being challenged and rethought—challenged in the spirit not of discarding, but of reinvigorating, area studies. In my case, I was always particularly interested in the links between South and Southeast Asia, and so oceanic history felt like it had a lot to offer.

That initially led me to a focus on transregional migration. But I realized that, in a lot of oceanic history, water is essentially just a space of transit—and this was true of my own early work in the field as well. I became more and more interested in the water itself, interested in thinking more “three-dimensionally” about the water through the history of oceanography and meteorology, for example. That is what led me to the project that became Unruly Waters: in trying to think of the water as more than just a space of crossing.

We can learn a lot about the past by thinking through water, and there are many scholars in different disciplines who have been doing this for a long time. Water can tell us a lot about inequality. It can tell us a lot about the history of science and technology. A focus on water allowed me to work across and bring together my different interests, which started off in the history of medicine and gravitated to the history of migration.

‘Global history’ figures in the very first line of Crossing the Bay of Bengal. How do you think about this field and how does it inform your work? What are the merits and/or limitations of global history as an approach?

I do not think of myself as a ‘global historian’—or at least, I do not use that label to describe my work. I think if I were to put a label on my work, I would tend to introduce myself as a historian of South and Southeast Asia. For me, that regional framing is a vital anchor and starting-point. To that extent, I feel like a fellow traveller in the project of global history: I am inspired by it, I learn a lot from it, I interact with colleagues who practice it, but it is not quite what I do.

Having said that, I am just starting work on the first book I will have written that does claim to be a global history. I am writing a very ‘big picture’ book on the environmental history of the modern world; but even as I begin work on it, I realise that it will be a global history told from the perspective of a historian of South and Southeast Asia.

I think the great strength of global history is its radically de-parochializing sensibility. I think it enables large-scale comparative work, which is nothing like the sort of work I do, but is work that I find exciting—work such as Victor Lieberman did in those prodigious books, Strange Parallels. Of course, I was particularly compelled by the way Lieberman writes global history from the perspective of a Southeast Asianist! The global perspective is well-suited to particular kinds of history. I have seen very exciting global intellectual history, and new histories of global capitalism. I do feel like environmental history is a fruitful area for new approaches to global history. It is something I am trying to work with currently.

“I have reflected a lot on the reasons why environments and nature had disappeared from a lot of the histories I was engaging with: I think the fundamental reason is a fear of and a critique of environmental determinism.”

In your latest book, Unruly Waters, you note the relatively recent "disappearance of nature from most broad accounts of historical change." But now, especially as climate change collapses an "age-old humanist distinction between natural history and human history," as Dipesh Chakrabarty argues, historians are indeed re-considering the role of the environment in the varied histories they seek to understand. How do you figure the role of the environment in history?

When I said I was struck by the disappearance of nature from a lot of general accounts of history, I was talking about work outside of the field of environmental history, which is a field that has flourished in the last thirty years or more. Environmental history as a field has a distinct intellectual trajectory and one which has been very enriching. If I think about what sparked my observation, it was rather to contrast the various kinds of economic and agrarian histories that were written in the 1970s—which were very closely attuned to landscape, closely attuned to the seasons, and of course to agriculture—with the kind of work that myself and others were doing in the 2000s: namely, a turn to the study of cosmopolitanism, diasporas, intellectual history, and port cities. I meant this as a critique of my own practice as much as anything else, in that I realised there was a sort of ‘disembodied’ quality to how I started writing about port cities, for instance in my 2009 American Historical Review essay on Tamil diasporas, in comparison with earlier traditions of historical work. Going back to Christopher Baker’s 1984 work on the history of rural Tamil Nadu (An Indian Rural Economy) was pivotal to making possible all of the work I’ve done since then.

In thinking about Dipesh Chakrabarty’s pivotal intervention (“The Climate of History”) I wonder if one of his key observations from 2009 remains true. His observation was that there is a gap between the “history of globalization” and the “history of global warming.” I still think most global history is not particularly interested in environmental history.

Yet, there are so many approaches to environmental history. I have just come to the end of teaching a course to sophomores here at Harvard called “What is Environmental History?” We started off this semester by reading John McNeill’s state of the field essay from 2003, “Observations on the Nature and Culture of Environmental History.” We were all struck by how, seventeen years later, the field has deepened, broadened, and gone in so many different directions. I am not sure there is a single answer to your question of what the role environmental history should be in relation to other kinds of history. I, myself, am especially interested in connecting environmental and economic history. That is probably how I would best describe my own intellectual project, and one I am still in the midst of working through.

I have reflected a lot on the reasons why environments and nature had disappeared from a lot of the histories I was engaging with: I think the fundamental reason is a fear of and a critique of environmental determinism. I completely understand that motivation and think it was probably a necessary corrective. If you think of the history of migration, the colonial story was that while “free Europeans” chose to cross the Atlantic to better their lives and seek their fortunes, Asian migrants were, in a sense, prisoners of climate. Quite understandably, much of the work in Asian diaspora studies since the 1980s has sought to debunk the colonial mythology and racial assumptions underpinning that narrative. In particular, work on Chinese migration has shown how important local and regional networks, family relationships, and even individual choice were. But we then reached the point where most works on migration and diaspora had nothing at all to say about climate, or about nature. And I think what we are seeing now is a move in many people’s work to reconsider the role of the environment—not as a determining factor, but rather as something to pay attention to alongside debt, family relationships, alongside all of the other things newer work has elevated to a much greater importance in understanding social change and migration in particular.

“If you think of the history of migration, the colonial story was that while “free Europeans” chose to cross the Atlantic to better their lives and seek their fortunes, Asian migrants were, in a sense, prisoners of climate. Quite understandably, much of the work in Asian diaspora studies since the 1980s has sought to debunk the colonial mythology and racial assumptions underpinning that narrative.”

In Unruly Waters and in your 2019 Cornell lecture, "Monsoon Asia," the question of inequality looms large. Can you elaborate the role inequality plays in the histories you study?

I think it is a central thread in my work. Inequality was important to my earlier book on labour migration across the Bay of Bengal. Some of that work was about the lasting and enduring effects of inequality in Malaysia, where a portion of society—including descendents of labour migrants who worked on rubber plantations—continue to experience marginalization and low social mobility. Unruly Waters, I think, deals even more centrally with inequality. What I found was that water was both an index and a driver of inequality.

It is an index of inequality in the sense that, clearly, one of the most fundamental social needs manifests itself in access to water. I am struck by how, in the current pandemic we are all living through, in which we were told from the very beginning that regular hand-washing is perhaps the single most important intervention is an impossibility in many parts of the world. That brought that point home. At one point in Unruly Waters, I mention one of Dr. Ambedkar’s first public protests, which was in Mahad, that sought to open the local well to Dalits. That one episode, one among many, gives a visceral sense of the relationship between water and inequality in the South Asian context.

But access to water is also, in itself, a driver of inequality. This is one of things that I focus on in the later parts of Unruly Waters. Particularly in South Asia, as Pakistan and India both turned to the exploitation of groundwater as an essential part of their revolution in agricultural strategies, the control of water itself fuels a rise in rural inequality.

On a much larger scale, meanwhile, I think inequality should be central to how we think about climate change: how we think about both differential responsibility for it and—of course—differential vulnerability to it.

A common appraisal and defining feature of your work is its literary eloquence. I am interested in what, as a historian, you think about the role of narrative, rhetoric, and style?

That is kind of you to say. I enjoy writing. I am interested in the craft and mechanics of it. For me, the writing is as vital and as absorbing as the research. But I do not think that has always been the case—it took me some time to find my own voice as a writer. My first book was a fairly traditional monograph based on my dissertation and my second book was a textbook about Asian migration. In those two books, I think I saw the writing as largely a way to present information and present arguments. It was only when I started work on Crossing the Bay of Bengal that I felt I had the freedom to find my voice as a writer. Some of that had to do with the security that came from having then reached a stage of my academic career when I could take more risks—I was very lucky to have that security relatively early on, in a way that is becoming more and more elusive for junior scholars today. I was also lucky to have a wonderful editor, Joyce Seltzer, at Harvard University Press who worked on that book with me.

More generally, I do think a lot about writing and learn a lot from writing in other genres and fields—the work of novelists and poets in particular. It is not so much about borrowing techniques, but just paying attention to other writers’ use of language and narrative. I also learn, of course, from the historians I most admire as writers, and many of them I am lucky to count as friends and colleagues—Tim Harper, Maya Jasanoff, Emma Rothschild, and Eric Tagliacozzo, to name just four.

My practice tends to be to write fairly chaotic and ramshackle first drafts, and a lot of the process (and the pleasure) is then in the editing. That is the stage at which my books have come together.

Writing is one matter, but research is another. In your last two books, you synthesize a tremendous amount of information. These books mediate environmental, cultural, and economic history, in addition to connecting different scales of history (from the level of human life, the state, environmental structures, and even the planetary.) In addition to archival sources, you also employ, at times, oral history and direct fieldwork. How is this achieved? What is your outlining process when starting or developing a book?

I think I am instinctively drawn to an eclectic approach. I enjoy archival work, but I also enjoy fieldwork. I certainly would not call what I do ethnography, as it does not have the level of immersion that an anthropologist would bring to it, but I do spend a lot of time in the places I study—and for me, informal conversations and observations of the landscape are very important ways of reading the archives and imagining the stories I want to tell.

I think back to one long summer I spent in Malaysia. This was 2007, when I was working on Crossing the Bay of Bengal. At the time it felt like an enjoyable, but unproductive summer. I had not been able to get access to the archives I wanted to look at—some had been closed, others I was not granted permission to use—and I felt I was just ‘hanging around’ a lot of the time. And it was only with hindsight that realized I could not have written Crossing the Bay of Bengal without that summer. It was all of the thinking and observing and the intangible sense that came from talking to people, from walking around, from being in a place that allowed me to make the connections I could not have made through archival sources alone. It is why I am so grateful for those foundations that continue to give out exploratory grants, which are not overly fixated on particular outcomes.

Each of my books consists of lots and lots of fragments. At the outlining stage I almost think of bringing them together as sort of a collage of different kinds of material. I often go through a number of outlines for each of these books and play with the different shapes they could take. In the end I have usually come back to a broadly chronological structure, because I do think that it helps me, as well as the readers, to see and understand change over time. But that is often juxtaposed with certain reflections from contemporary conversations or observations—and I try to weave that in with the archival and historical material.

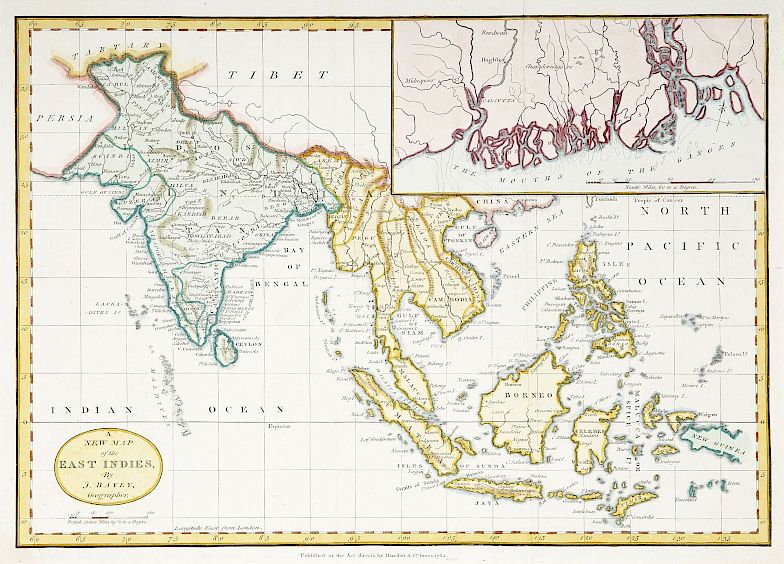

A recurring phrase which I noted and admired in Crossing the Bay of Bengal is "from author's collection." All the printed photographs in that book (and several in Unruly Waters) are taken by you and several historical maps are reproduced from your collection. I am interested in how personal archiving, curating, and collecting figure in your practices as a historian?

I love the way you put it. I am not a collector in the way some of my friends and colleagues are, in that there is nothing systematic about my practice and it is not something that I sort of pay particular attention to. To the extent that I collect any material of this kind, it is cartographic. I do love maps and have them around the office and the house. If I stumble across any historical maps, particularly of the Indian Ocean, I get excited. So, I am not a systematic collector in any sense, but I do accumulate stuff on my travels and I find that has been important to me.

I did not set out to use all of my photographs in Crossing the Bay of Bengal, but thought as we got toward the design stage: why not? I am by no means a skilled photographer, but it is important to my practice, even when I am writing, to have visual reminders, especially if I am writing far away from South or Southeast Asia and if I am writing at home or in Cambridge or wherever I happen to be. I do find having my own photographs with me helps in the process. I continue to take a lot of photographs, in an amateurish way, and find it helps me at every stage of the process—in the planning and writing, whether or not I use them in the book or not (that decision, in a sense, comes later).

Histories of the Indian Ocean have long been written, but today, I sense there is a growing popular literature that views this space from an increasingly "strategic" perspective—in emphasis, for instance, of avowedly military, diplomatic, or economic concerns. Epitomized by books like Robert Kaplan's Monsoon, which announces the Indian Ocean as "the coming strategic arena of the twenty-first century," how do you see the future study of this region of the world being conducted now and hereafter?

In the last part of my research for Crossing the Bay of Bengal, I encountered the “strategic studies” literature on the Indian Ocean for the first time. I had previously been ignorant of it, and it was a revelation for me. I think there was something like a division of labour when it came to studying the Indian Ocean: when I was researching Crossing, few if any histories of the Indian Ocean went beyond the 1940s, and quite a lot of them stopped in the 18th or the 19th centuries. So, I was initially surprised to encounter a growing literature in strategic studies that saw the Indian Ocean as an urgently contemporary region, indeed as a region of the future. I tried in the final chapter of Crossing the Bay of Bengal to make some of the links between the long historical view and the forward-looking work that you mention. I did so in a limited way, but it seems to me that since then (and it has been almost ten years since writing that book!) the field has continued to grow.

I am excited by new approaches to the contemporary Indian Ocean. There has been interesting work by anthropologists on the contemporary Indian Ocean. I think they offer a very different perspective from the strategic studies view, but equally see the Indian Ocean as a living region, a region that has been reconnected in various ways. I think of the work of anthropologists who have been working on labour migration from South Asia to the Gulf states, for example, or the wonderful “Indian Ocean Worlds” project brought together by Smriti Srinivas and her colleagues at UC Davis, which was explicitly about Indian Ocean worlds in the contemporary moment. I think there is a lot that is exciting there. Historians, too, have been moving into the 1950s and 1960s, thinking about the Indian Ocean in the Cold War and in relation to the Bandung moment. I think the Indian Ocean field is in, a very positive way, going in lots of different directions. It is no longer just a “strategic studies” view that deals with the Indian Ocean in the present. I am glad to see more and more work from an environmental perspective on the Indian Ocean that is coming both from the work of scientists and those working in the social sciences.

Having said all of that, I learned a lot from what I read in strategic studies. In a sense, that field was taking the Indian Ocean much more seriously than a lot of the humanities and social sciences were from the 1990s onward, and for a while the rest of us were playing catch-up. Obviously strategic studies is asking very specific questions about the Indian Ocean, and is interested primarily in great power rivalries—and I certainly do feel that there is much more to the Indian Ocean than just that, as important as those questions are.

The last question I want to ask: a biographical detail about Dr. Sunil Amrith that one cannot escape is your love of jazz—can you share a few recommendations for us?

Well, absolutely, that is a very important part of my life, which has not intersected with my academic work, and probably best to keep it that way! Jazz is for me a great source of inspiration and pleasure. My relationship with music has changed since I became a parent—I have two young children, six and two, so I can’t go to gigs in the way I used to. But I still listen constantly. The jazz musicians I am most excited about are contemporary, improvising musicians. I love classic jazz too, of course, but my recommendation is to listen to Jason Moran—everything he plays is magic. My Harvard colleague, Vijay Iyer, is another person whose music I find endlessly enriching and exciting. In this time of quarantine, there are so many musicians who have been putting things out from home, trying to do something despite the devastation this pandemic has had on performing arts of all kinds. I can only begin to imagine the effects it has on jazz musicians in particular. I am certainly grateful for what has been shared with us all from many musicians’ living rooms at this time, and I hope we can find ways to support and sustain the music.