Toynbee Coronavirus Series—Global Historians Analyze the Pandemic: Glenda Sluga, Jie-Hyun Lim, Lauren Benton, and Hsiung Ping-chen

Living through historically unprecedented times has strengthened the Toynbee Prize Foundation's commitment to thinking globally about history and to representing that perspective in the public sphere. In this multimedia series on the COVID-19 pandemic, we will be bringing global history to bear in thinking through the raging coronavirus and the range of social, intellectual, economic, political, and scientific crises triggered and aggravated by it.

Toynbee Coronavirus Series—A Global Historical View of the Pandemic

Historians' Statements

Participants:

Glenda Sluga, University of Sydney/European University Institute

Jie-Hyun Lim, Sogang University

Lauren Benton, Vanderbilt University/Yale University

From pandemic to planetary thinking

Glenda Sluga, University of Sydney/European University Institute

For a long time now my job as an historian has been to understand how, when, and why, humans have conceived of and supported inter-governmental bodies (the best known of which include the United Nations, the World Health Organization and the World Trade Organization), or, more simply, international ideas. Last year, 2019, marked a hundred years since the peace treaty settled by the victors of World War I, invested in this ‘international thinking’. They had as their goal the prevention of a repetition of what had happened in 1914, when Europeans ‘sleepwalked’ their way into war. The 1919 Treaty of Versailles established inter-governmental organizations as a foundation of a new international order —reflecting the demands of popular movements as much as politicians. For a gripping human glimpse of this early twentieth century mood, dip into the Australian novelist Frank Moorhouse’ deeply researched trilogy Grand Days, which tells the tale of the Geneva-based League of Nations (the UN’s predecessor). Out of one of the twentieth century’s darkest moments, the world gained the seeds of a system of a multilateral international order intended to represent and assist an expanding cohort of member nation-states.

We now have an increasingly clear picture of a century during which the public and political fortunes of this international thinking rose and fell, depending on whether it was perceived as an antidote to nationalism and war, or an actual threat to national sovereignty. The status of an ‘international’ order peaked in moments of despair, in the midst of the most terrible wars. It flourished in the relatively brief moments of opportunity at the end of these wars, with the promise of peace-making. And, even more surprisingly, exactly fifty years ago, in the midst of the Cold War, it led to an even more ambitious idea, ‘planetary thinking,’ in anticipation of an environmental crisis that would pose an even greater existential crisis for humankind.

In 1969, the UN Secretary-General U Thant called for a planetary imagination that could match ‘the realities of the present-day world.’ At that time, those realities included the technological abilities that put humans on the moon, and the world-scale environmental concerns that provoked the UN General Assembly to organize the world’s first international conference on the environment. Eventually held in Stockholm in 1972, the UN Human Environment Conference brought together around 113 governments and 700 NGO accredited observers as well as a broader public. It even included an official forum that gave voice to non-governmental environmental organizations. The history of the Stockholm conference presents us with a disorienting picture of the long notice we have had of a looming, fossil-fuel fuelled environmental crisis of planetary proportions, and an international order already grappling with that same crisis by adopting a ‘planetary’ perspective. The UN Human Environment conference gave legitimacy to almost a decade of planetary thinking—whether as planetary realism or planetary imagination. The anthropologist Margaret Mead and economist Barbara Ward captured this mood as they promoted the Stockholm conference as the ‘starting point for a new sense of planetary realism—beyond our narrow nationalisms, our divisive ideologies, our gulfs of wealth and poverty.’ They wanted this planetary realism to acknowledge ‘all human life, black, white, communist, capitalist, wealthy, ... depends for sheer survival on the health, fertility and balance of the earth’s life support system, on the oceans, air, and climates, on the soils and harvests, which we all have to share and which we can irretrievably damage. This is the ultimate rationale for world cooperation.’ Just as some of the Stockholm discussions stressed a vision of the order that acknowledged the earth’s fragility, the conference briefly manifested a popular as well as scientific and governmental engagement with these issues. It inspired economic solutions grounded in these equity questions, with an eye to social justice across the planet as well as within nation-states.

In the same 1970s moment that produced the Stockholm environment conference, another approach to the global was in germination—the global as globalization, with an emphasis on the rise of multinational companies, and the marketisation of the world’s economies. The planetary view preceded a global perspective in the changing awareness of the world around us, and our connections to it. But the importance and the relevance of the planetary was all but wiped out by interest in the global as a paradigm that referred to industry, commerce, and trade, the rise of multinationals, and the transnational, and the cross-border flows of money. At the crossroads of international, planetary, and global thinking sat the fundamental reconceptualization of capitalism that we now think of as neo-liberalism, with its privileging of markets, and the reconfiguring the international, planetary and global as more simply, and reductively, globalization.

If there is one thing historians are useful for, it is anchoring the present, providing moorings that allow us to take stock, to navigate the future with a sense of where we have been and how we got to where we are. Before the pandemic, and after there will be the connected existential challenge of climate change. Yet there has been little political acknowledgement of the deep connections between environmental and epidemiological disasters. Curiosity or action seem limited to Wuhan as the problem—wetmarket or lab, or maybe WHO? There are warnings that we are ‘sleepwalking’ our way to planet-scale climate catastrophe—just at the moment when our most useful mechanisms for tackling that catastrophe, the inter-governmental foundations of the existing international order, are cracking up.

These days the challenges we face are a question of imagination as much as policy. We have invented new words such as ‘anthropocene’ to designate the current geological age as the period during which human activity has been the dominant influence on climate and the environment. But it may also be time to remember the long, interrupted history of ‘planetary thinking’ and to remember just how long we have known about climate change, and had at our fingertips a range of solutions, many of which we continue to resist.

At the least, a turn to ‘planetary thinking’ should be useful for imagining new approaches to the entangled economic and political problems that beset our fickle embrace of the world as a planet. I am not the first to argue that our governments might be ‘sleepwalking’ their way to environmental catastrophe, as willfully as, a little more than one hundred years ago, they ‘sleepwalked’ their way into a world war that devastated generations.

Witnessing the COVID-19 as a Global Historian

Jie-Hyun Lim, Sogang University

Viruses have often unexpectedly connected the world. In this respect, COVID-19 has not betrayed our expectations. Among the numerous images of the world that COVID-19 has connected, two cases stand out for the ways in which unexpected links are being made – real or imaginary.

One is the far-right theories of a Jewish-Chinese COVID-19 conspiracy, an ideological pandemic sweeping the anti-Semitic dark webs. Anti-Semitic images of Jews as poisoners and deliberate carriers of the disease are history-ridden, going back to the Middle Ages. What is new is the idea of Coronavirus as a global plan engineered by the Chinese and Jews together. A neo-Nazi “dark web” in the USA proclaims the coronavirus to be a Jewish-Chinese conspiracy. Age-old anti-Semitism is thus conspicuously combined with a twenty-first-century version of the “Yellow Peril” bound to the fear of the rise of China as a global power. The nostalgia among Americans for a lost global hegemony, which produced Trump’s slogan of “MAGA: Making American Great Again,” stands behind that weird combination of imaginary threats. The fear of the Coronavirus and the White House’s incompetence to cope with the pandemic has twisted postcolonial melancholia in the USA into a global suspicion of anti-Semitism and Yellow Peril, which evokes memories of the witch hunts and pogrom during and after Black Death in medieval Europe.

The other example is the story of the Irish charity drive for people in the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Reservation suffering in the Covid-19 pandemic. Irish donors are repaying the old kindness of the Choctaw Nation. The Choctaw people sent $170, an equivalent of about $ 5,000 today, to starving Irish families during the potato famine in 1847. The Choctaws were the first tribe to be relocated during the “Trail of Tears,” starting in 1831, with thousands dying and many starving. Many Irish donors cited the generosity of the Choctaws, noting that the gift came not long after a forced march across thousands of miles known as the “Trail of Tears.” A sculpture in County Cork, a circle of 6-foot-tall feathers that make the shape of an empty bowl, symbolizes the kinship between the spirits of the Native Nation and the hunger suffered by the Irish.

Much of the global history of the pandemic may stand between the above two extreme poles. Human beings as a species are generically neither good nor bad. Nor both. Their responses, perceptions, performances, thinkings, practices, diagnoses, and solutions are too diverse to be comprehended in one stroke of the pen. Nevertheless, those diversities come from different ways of perceiving realities and practicing the world, which can be traced and analysed. Judged from the observation today, three sets of tensions are structuring the historical interaction between human beings and viruses: 1) power relations between capital and labor, 2) archetypal political tensions between individual and state, 3) responsibility for climate change between Anthropocene and Capitalocene.

1) As COVID-19 spreads, many employees are being advised to work at home. Its rationale was to cut business costs as much as the risk of infection by reducing commuting and office hours. Soon people began to worry that they would never come back to the office because the automation of systems, accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis, would not need the same scale of workforce as before the crisis. Immediately, it reminded me of the “Brenner debate” of the late 1970s and early 1980s on whether neo-Malthusian cyclic accounts of population and development or social class explanations best accounted for economic change in late medieval Europe. As home working becomes dominant, the scales are tipped in favor of capital because of the shift of the labor/capital ratio. Home-working will accelerate the automation of office and manufacturing work, and the competition for jobs will heat up. After the fall of really existing socialism, COVID-19 is unexpectedly proving to be a second major blow to labor. As Darko Suvin has stated explicitly, the best analogy for Coronavirus is not SARS but the Great Depression of “1929 without Leninism.” For the majority of socialists who do not think Leninism saved us then, let’s say “1929 without socialism.” If we stay free from the (neo-) Malthusian determinism of population theory, however, we can expect an unexpected reversal, with the balance tipping in favor of labor. Relations of production between capital and labor also depend on the class struggle, political negotiations, social compromise, interest tradeoffs, etc. For instance, the introduction of the “disaster income” for the socially weak and, eventually, all community members may help to institutionalize the “basic income” in post-COVID societies. A historical memory of the decay of serfdom and agrarian class struggle in the post-Black Death medieval Europe may be helpful for us in imagining the post-COVID world. The role of historical actors as much as the structural change of labor/capital statistical ratio proves to be important. It is a good sign that more people recognize the importance of the unions and join up.

2) The age-old tension between the individual and state has been one of the central issues raised by COVID-19. In the face of the high fatality from the disease, the ontological security issue for individuals was so overwhelming as to bury the issues of bio-politics and high-tech surveillance. Giorgio Agamben’s concern about bio-politics has often been ridiculed. The efficiency of South Korea in controlling COVID-19 was one of the focal points for this debate. In contrast to the medical laissez-faire inherent in the theory of “herd immunization” in Great Britain and Sweden, the South Korean government tightened the grip of existing controls on the population with consent from below. The efficiency of the patronizing state in South Korea has been subject to polemical debates around the balance between individual freedom and collective security. To what extent may the authority execute the coercive power entrusted to it for the purpose of public safety? In the case of COVID-19, where is the dividing line between medical welfare and medical pre-fascism? What is the difference between the political emergency and medical emergency? Per contra: How can we evaluate the principle of rationality that would prioritize “the saved” over “the drowned” based on the calculation of probability? In the absence of effective “policing,” the warring Emergency Room in almost every hospital becomes a history lab for “Leviathan 3.0” as the rationality of survival contradicts the morality of humanity in a state of emergency. On the other hand, the excessive “policing” to avoid that situation may produce a hygienic dictatorship. With the massive support from below, it may constitute a grotesque behemoth worse than the mass dictatorship in the twentieth century.

3) One unexpectedly good result of the COVID-19 is that Koreans are able to enjoy the blue sky and fresh air. The drastic measures of social quarantine and factory lockouts in China closed down the source of the yellow dust that pollutes the air. Originating in the Gobi desert, that dust blows eastwards through the industrial zone on the coast of the Chinese Sea into the Korean peninsula. It has deprived Koreans of the blue sky and fresh air in spring and, increasingly, all four seasons, seriously and chronically threatening the respiratory condition of Koreans no less than COVID-19. Similarly, North Indians can enjoy the long-distance landscape of the Himalayan mountains because the factory closures and reduction of traffic have returned the blue sky to them. It is a wonder to get back the blue sky and clean air in such a short time after the lockout. That experience has made us a bit reserved about the term “Anthropocene.” Anthropocene leads us to a kind of reductionism to attribute the environmental crisis and climate change fundamentally to humans as species-beings. But a quick return of the blue sky and clean air to Northern India and the Korean peninsula after the COVID-19 lockdown implies that disastrous climate change is an essential manifestation of capitalism. I have no ambition to idealize human beings, but it is capitalism as a human-made system that is the main culprit here, rather than abstract human beings. The distinction between Anthropocene and Capitalocene will be crucial in writing the global history of capitalism and modernity.

What else? During the drastic transition from socialism to capitalism in post-communist Poland in the early 1990s, many people suffered a lot. Whenever asked about their situation, they used to answer “Jeszcze żyję (I am still alive).” What is vital for a global historian (or whomever) at the moment is “Jeszcze żyję.” Dear friends, please stay safe. We need to survive to discuss more and later.

A dangerous metaphor

Lauren Benton, Vanderbilt University/Yale University

In drawing on world history to better understand the Covid-19 pandemic, historians have logically turned to the history of disease. Attention to histories of the Black Death, the Spanish Flu, AIDS, and other pandemics has generated some valuable insights. Comparing mortality rates of different cities during the Spanish Flu outbreak affirms the value of social distancing. Literature on the plague shows that humans who lived long before us experienced the profound weirdness of daily life under quarantine.

World history has still more to offer in these troubling times. While working on a book about small wars in world history, I have been thinking about some ways that the global history of warfare can help us analyze the politics of the pandemic.

The gist is this: world history cautions against the easy acceptance of the metaphor of war. Little about war as a social phenomenon is as simple as the metaphor implies. And, as we have recently witnessed in the U.S. government’s militarized response to protests against racism and police brutality, war talk presents some startling dangers.

The metaphor of war has been ubiquitous during the pandemic. In mid-March, as the absurdity of President Trump’s prediction that the novel coronavirus would resemble the common flu was becoming increasingly apparent, the president began referring to Covid-19 as the “invisible enemy.” Within a week of first using that term, Trump declared himself to be “a wartime president.” The media liked the metaphor, too. The press began referring daily to healthcare workers, meat packers, and others as laboring “on the front lines.” Politicians labeled essential workers of all kinds as “warriors.” Politicians informed citizens that we were “under attack” by the virus and that they would lead our “defense,” as if formations of molecules were massing along our borders.

Even critics of President Trump adopted the language of war. Perhaps winning the imaginary sweepstakes for best quips about Trump’s failed leadership, Governor Jay Inslee of Washington state responded to the Surgeon General’s comparison of the coronavirus outbreak to Pearl Harbor by asking, "Can you imagine if Franklin Delano Roosevelt said, 'I'll be right behind you, Connecticut, good luck building those battleships'?" Inslee was resisting the comparison of Trump to FDR, but he had nothing against the premise of pandemic as war.

There are some obvious political reasons that Trump and other world leaders turn to the language of war in times of crisis. History teaches that by assuming the mantle of wartime leaders, politicians can benefit from significant, if temporary, bumps in popularity. More fundamentally – and more ominously – the specter of war bolsters the case for emergency measures, and for stronger and even exceptional executive powers. On the most basic level, war talk during the pandemic seeks to turn workers into foot soldiers supposedly willing to support the war effort through sacrifice, even if that sacrifice must involve illness and death for them and their family members.

We can go further and draw other insights from the global history of warfare. Some emerge from the recent history of the global “war on terror.” Others are rooted in the much earlier history of small wars in world history. And still others relate to the history of imperial violence.

The history of the “war on terror” has shown that the language of war can provide expansive cover for attacks on domestic rights and acts of violence abroad. One characteristic of the “war on terror” is that it is open-ended, with no diplomatic event imagined as bringing resolution. The “war” also assumes a rapidly changing cast of enemies operating on unspecified and shifting ground. Drone strikes in Somalia against Al Shabaab and the “targeted killing” of General Qasem Soleimani on an Iraqi runway find their way, along with scores of other strikes against multiple other actors, onto lists of supposedly legitimate acts of wartime aggression.

The global history of the “war on terror” has undoubtedly affected how some people hear the language of war in relation to the pandemic. While the duration of stay-at-home directives has hogged the public’s attention, the purposely vague ending dates of other supposedly temporary “wartime” policies have gone unexamined. That set of measures includes a host of regulatory adjustments, from restrictions on border-crossing to fundamental changes in regulatory processes. Characterized as part of the anti-virus “war” effort, such policies go to the root of the state’s capacity to govern. As the historian Peter Lake has observed, the strategy allows the right to run a populist campaign against its own failed state. This sort of regulatory change tucks consequential policy actions into the recesses of already half-moribund government agencies, which can then exercise a uniquely toxic combination of fecklessness and arbitrary power.

The legal scholar Daniel Hemel has pointed to an example of how linking virus response to national security can produce this result. He observes that the conventional understanding of Trump’s executive order on meat packing plants got it wrong. The press and public assumed that the president already possessed broad constitutional powers over the food supply and interpreted the order as a clear directive to meat packing plants to stay open. But the absence of explicitly broad powers led the order to focus on a structural change to the regulatory process: it delegated Trump’s authority over the food supply chain, however interpreted, to the Secretary of Agriculture, Sonny Perdue (insert obvious joke here about the chicken magnate guarding the hen house). Further, the order defined this change as effective for the duration of “the national emergency caused by the outbreak of Covid-19 within the United States.” How long will that be? Nobody knows. Refer back to the war on terror.

As Kim Scheppele has shown in analyzing the war on terror as a global phenomenon, this kind of maneuver can repeat itself across national governments with very different ideological orientations. The countries of Western Europe have been as adept as less liberal states in altering domestic institutions and expanding law enforcement capacities to advance a vaguely defined “war on terror.” In the pandemic so far, observers have worried about the Covid-19 crisis response as cover for the acceleration of environmental degradation in Brazil and the further restriction of civic rights in Hungary. The global history of the “war on terror” suggests that we should extend our gaze very broadly in analyzing institutional changes justified by the language of war and emergency during the pandemic.

As we look further back in global history, we find other touchstones for analysis of the pandemic. Campaigns of imperial violence ranging from brutal crackdowns of uprisings to quotidian forms of colonial social control often represented subjects simultaneously, or in quick sequence, as enemies and traitors. Imperial officials toggled easily between labels of war and rebellion. This ambiguity about whether subordinate political communities were inside or outside empires fashioned a convenient framework for a broad spectrum of violence.

Looking back still further, we find that for many centuries, war was not fought in ways that we might now assume. For centuries, raiding represented a globally occurring way of war, and it persisted in periods of peace, as permanent background to cross-polity trade, migration, and tributary arrangements. Most of the campaigns that historians call “conquests” consisted of series of raids targeting unfortified towns and rural populations and building toward attacks on richer, fortified settlements. At the gates of towns, armies populated by experienced raiders demanded surrender in exchange for promises of some protection of property and lives. They unleashed horrific violence after punishing sieges if terms were not met.

This pattern of violence was truly global. It was familiar to Romans, Mongols, and Aztecs; it informed the strategies of Spaniards in the Americas, Marathas in South Asia, and Comanches in North America. Conquerors pointed to broken promises of peace as the reason for violence, in effect blaming the victims of imperial aggression and characterizing conquerors as peacemakers.

Long phases of chronic violence – the Crusades, for example, or the so-called Reconquest of the Iberian peninsula—were not discrete wars but series of raids and skirmishes set within a framework of shifting alliances. Most historical conflicts look more like the present-day war in Syria than World War I. Fighting that we once imagined as occurring on a single, moving “front line” turns out to have unfolded across an intricate landscape of embattled enclaves and moving, porous frontiers.

If the metaphor of war in our response to the Covid-19 pandemic referenced these qualities of war, it might make better sense – though it would be no less dangerous. Rather than pointing to certain groups of essential workers as being on the “front lines,” we might imagine scattered skirmishes against recurring flare-ups of danger and contagion: a great multiplicity of “fronts.” And we might anticipate a stop-and-start “battle” in which reverses would be structural features continually breaking easy progress toward “victory.”

But I don’t want to advocate merely getting the historical references right. The political effects of the metaphor of war are too often insidious, and too unpredictable. Historical precedents make the subtexts of the discourse of war no more palatable. Powerful, armed polities still want to claim the mantle of peacemakers, portray fractured groups as unified, and label dissidents as enemies and traitors.

Much sooner than many of us expected, in fact, the easy acceptance of war talk circulating during the pandemic has influenced other phenomena. The violent repression of protests in U.S. cities appears to draw strength indirectly from the easy boundlessness of war talk. The U.S. president and attorney general quickly labeled protesters in American cities as “domestic terrorists.” Republican Senator Tom Cotton went so far as to state that there should be “no quarter” for protestors. There is no indication that he was speaking metaphorically, but even if he had been, critics pointed out that his words evoked not just war, but war crimes. The right soon discovered that citizens make better, more tangible enemies than an elusive virus with tiny crowns. We have met the “invisible enemy”—and they are us.

The allure of the language of war, after all, is precisely its formlessness. If listeners hear “war” and imagine World War II – rather than, say, Algeria or Vietnam – they will think of the mythic “good fight,” and they may be less attentive to the way calls for sacrifice can shift attention from destructive policies. If, instead, audiences hear the call to war in ways conditioned by the war on terror, they will be prepared for an ever-expanding list of enemies and vague objectives. In either case, war talk can produce cover for political actions with shockingly little relevance to controlling the virus outbreak and with enormous potential to justify brutal repression and sharpen inequality.

Perhaps the clearest lesson from the global history of war is that our assumptions about war are not reliable. Nor is the metaphor of war a good guide to public policy—in a pandemic or in a period of protest. We cannot control what our political leaders say, of course, and we can even expect them to continue to favor war talk. But we can at least limit the use of the world’s most dangerous metaphor by refusing to repeat it.

Notes from a Historian

Hsiung Ping-chen, UC Irvine

Continuously caught in the waves of “surprises” that the media delivers daily surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, it is a challenge to allow historians to speak if the public believes that current events are, in fact, truly “unprecedented.”

Forget for the moment precedents in the high Classical Era, even though archaeologists fed us fresh evidence of the Athenian Plague (430-427 BCE) as recently as 1993-1994—with massive graves of hasty burials of young and old confirming Thucydides’s telling (two millennia ago) of the horrific plague that overwhelmed the Peloponnesian War, and which ended the Athenians’ battles with the Spartans and tug of war with the Persians. Benefiting from hindsight, which progresses with our evolving knowledge of bio-medicine, we see now that the Greeks should have noted the public health hazards they had situated themselves against, with the pouring in of refugees, crammed together, short of food and space, and deplorable conditions for hygiene. Though of course they cannot be faulted for this lack of knowledge. Similarly, we cannot blame the general population for its oblivion of the threat that movements of goods and people across the Eurasian Continent posed in the 14th Century, unaware of the public health pressure mounting from the East on the eve of the bubonic and pneumonic plagues known as the Black Death (1347-1351).

Historians have also long reminded the general public of the meaningful, if not positive, outcomes that can also attend massive disasters. The Peloponnesian War and the Athenian Plague partly prepared the stage for the end of the Classic Era and the unfolding of the Hellenistic world. Medieval European historians certainly taught their audiences that that’s what the unbelievably tragic Black Death had cleared the ground for: the ushering in of new lives throughout towns and countries in post-pandemic fifteenth-century Europe. Labour commanded higher value now, working the cleared lands swept by the plagues, and the hustle and bustle of towns and cities treated surviving Europeans with the prosperities and gaieties of urbanization. This paved the way for the period of discovery people later called the ‘Renaissance.’

Surely none of this had been planned as such. Nevertheless it remains surprising that, even after William McNeil, narratives of the plague and its outcomes and actors have rarely been incorporated into the main stories of history—they remain on the side lines attending other historical events. Epidemics are unwelcome jolts not only to the ancient populations that experienced them, but also continue to be so for historians. Thus we receive the outcries of endless “unprecedentedness.” Plagues and pandemics will always plague the “unconscious consciousness.”

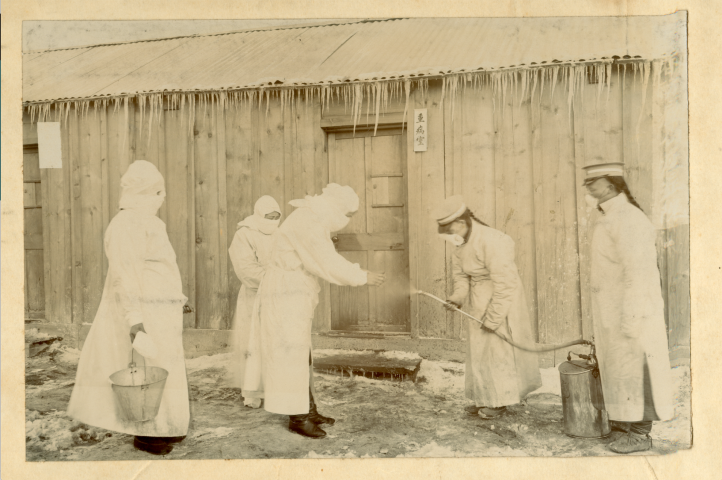

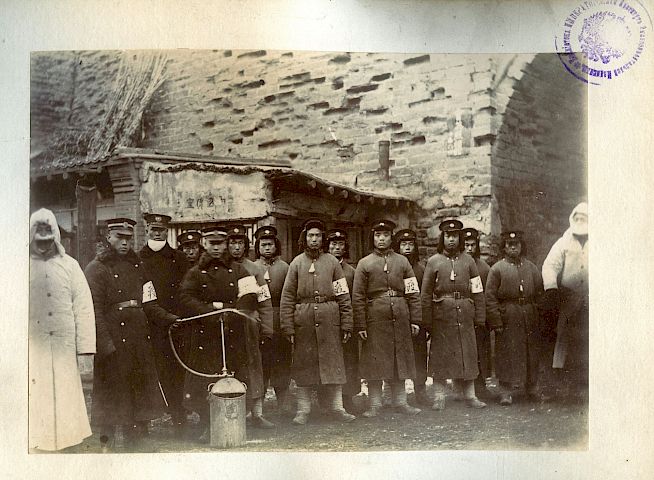

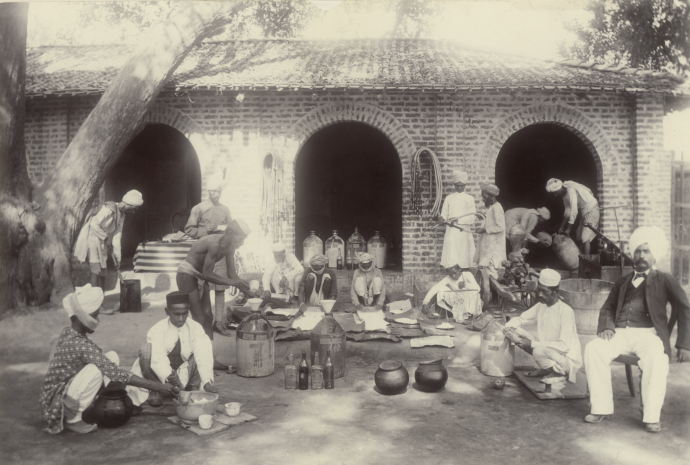

Small surprise then that diseases have been made to wear the wrong names (e.g. the Spanish Flu and the “Manchurian Plague (1910-1911)” and that national and regional labels stuck in the midst of imperial power fights. But this has been a long problem, originating well before the advent of sustained transnational and transcultural discourse. So, from where and when will be begin to critique such “naturalized” story telling around pandemics and external threat? When will “global history” address what pandemics really represent for humanity? In the seventh century, when the transcultural Tang Empire ruled China in close connection with Inner Asia and the Eurasian continent beyond, Prime Minister Wei Zheng (魏徵 580-643) wrote in his memorial to Emperor Tang Taizong (598-649) that, in addition to adjusting his own cap and gown as he looked into the mirror of bronze, he wondered what he would see and how he should adjust if he were to look into the mirror of history (以史為鑑)–seeing the whys and hows in the “rise and fall of matters” (知興衰).

It was also in that era that the best physicians in the empire, such as Sun Simiao (581?-682), reminded medical colleagues that the goal of medicine ought to be treating ailments before they arise (上醫治未病). Public health and preventive medicine were not yet fully formed concepts and practices, but the ideas were already clear. When will we ever learn that lesson, however? During the prior severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic, petrified East Asian populations learned to wear masks and practice social distancing, as street people in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China will attest. Is this what epidemics in history should have been about? In addition to social distancing and lock downs, what sort of communal ground would the larger collective be able to work with if we had a different History circulating and going viral against the COVID-19? Will global historians team up with social media voices and the medical workforce during the next crisis, or in order to surmount this one?