Unexpected Guests? The Soviet Union and the History of Global Capitalism: An Interview with Oscar Sanchez-Sibony

Capitalism versus Communism. To many, the latter half of the twentieth history was deeply shaped by the confrontation between these two ideological and socioeconomic systems. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, capitalism's triumph was credited to its valorization of money and protection of markets, among other factors; and, as the story continues, Communists failed, in part, because they suppressed markets and globalization.

Yet, how much of this historical picture holds true? To Oscar Sanchez-Sibony, a good deal of Cold War histories are founded on generally held misconceptions about the political economy of the Soviet Union. Not only do they ignore the intense engagements between the Soviets and the world, they often miss the mark by neglecting the larger financial and economic architecture that facilitated such exchanges and economic growth in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). There is a larger story to be told about the rise of global capitalism and the Soviet Union.

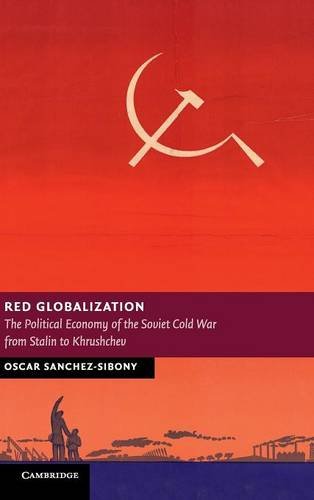

These are the themes of Red Globalization: The Political Economy of the Soviet Cold War from Stalin to Khrushchev (2014). Making use of archival documents from Russian archives, Sanchez-Sibony provides a rich account of how a young Bolshevik state navigated through the world's economic crises, while seeking favorable trading partners in the West for investments. This interview also ventures into topics and figures such as Depression Stalinism, Anastas Mikoyan, and Soviet-Global South relations. This book provoked much debate, and will be a must-read for years to come for anyone interested in histories of the Soviet Union, global capitalism, and the global Cold War.

Oscar Sanchez-Sibony is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Hong Kong, where he teaches and researches subjects in Soviet history, Stalinism, and capitalism. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago under the guidance of Sheila Fitzpatrick. Toynbee Foundation had the pleasure to talk with him about his career and the development of his research.

— Rustam Khan

KHAN: Can you tell us what drew you to Soviet and economic history?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: I never have a good answer to that question because I chose Russian for no particular reason when I went to college. Initially, I wanted to study Chinese, but I was warned away from it by others because of an old, exotic idea about its difficulty. I opted for Russian so that I could go abroad and travel for a semester. And look at what happened!

My studying economics made more sense. My father is an economist, so I grew up with it, regularly reading the business and economics sections of newspapers. Although, when I pursued the Ph.D., I didn't take up economic history until well after I should have. I was initially planning to study international relations, then veered into social history inspired by my advisor, Sheila Fitzpatrick, before she guided me back to international relations.

As I progressed in my graduate studies, I was set to examine Soviet-Cuban relations, but found that it was not going to work out in terms of archival documents, because some archives in Russia were then closing down. I ended up stumbling into the political economy of the USSR, which is something I probably had a comparative advantage in given my upbringing. I was also greatly influenced, in particular, by Bruce Cumings at the University of Chicago, who was trained in and published on political economy. So, it was fortuitous, but it has also been an issue for me in that I've found myself in an in-between position in the field.

KHAN: What was the genesis of Red Globalization, and were there surprising moments in your research for the book?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: I had defended a dissertation proposal on Soviet-Cuban relations, and my thesis was primarily supposed to be about their political relationship, but with excursions into cultural and economic entanglements. However, I couldn't access the foreign ministry archives, so I went looking for documents on Cuba in the state and economy archives in the meantime. For the period I was looking at, you couldn't get your hands on a nice Cuba file, so you had to retrieve relevant bits and pieces out of a larger stack of documents on Soviet international relations. Inevitably, I was reading all these other sources that spoke against the idea that the USSR was an autarkic endeavor. At the time I didn't notice much else, but this was pretty foundational.

Six months into my archival research, I realized that my original approach wasn't going to work out, and I decided to change my subject to the political economy of the Soviet Union. But, I didn't know what this topic would ultimtely look like, because I hadn't prepared the subject. Once back in Chicago, I had to teach myself about the Soviet economy because it was not being taught, even though economists and political scientists in important ways had made the field. My brother, who is a political scientist of Latin America, guided me through the political economy literature, and I finally came to understand where Bruce Cumings was coming from, so in putting those things together and employing the archival methodology Sheila Fitzpatrick had taught us I was able to cobble together the dissertation.

When you read 'globalization,' you imagine that there is a "normal" kind of globalization and then that there would be a supposedly very different "red or communist type," which is, of course, something like the opposite of what the book argues.

KHAN: Can you explain the title? What do you think of the notion that in using the term 'globalization' in its neoliberal economic meaning you might be denying the socialist world its own understandings of the term and its own ways of creating an alternative globalization?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: The title is more of an attractive name rather than a theoretical positioning, but I came to like it because it was also clearly transgressing what people assumed of its meaning. When you read 'globalization,' you imagine that there is a "normal" kind of globalization and then that there would be a supposedly very different "red or communist type," which is, of course, something like the opposite of what the book argues. So, it plays on the assumption of the field. All I want to convey is that this is an important aspect of how socialist geographies were experiencing and participating in the processes of globalization.

I am of the belief that there is something systemic about what happened to the world during the post-World War II period. This thing is usually called capitalism, which acts on the world as it encounters it, generally speaking. Further, if you have a project that is developmentalist, as all socialist projects were, you inevitably come across this system, particularly if you, as a government, are interested in drawing capital or technologies from this system. In this sense, I am less interested in what socialists thought about globalization and I am more intrigued by the systemic power that operates as they engage with international capitalist institutions. I am not denying the power of socialist imaginaries, but I think that the power of capital and engagement with capital is critical to understand what happens socially and politically in the USSR.

KHAN: The international financial system after the First World War, the gold standard, and consequently the Great Depression plays an important role in your book, and you approached these themes differently than others in your field have done. Could you tell us more about your approach and thinking?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: What I am doing in the book is to grapple with Soviet history against the historical context of international political economy (IPE). Not only can you do so, but I think it's important to so do. Historians of IPE usually tell us the story of the gold standard and the failure of policies that it engendered, leading to the Great Depression. While, IPE doesn't tell us why Nazism took the form it did or about the specific outcomes of different countries, it gives us a general understanding of what it was that created the space for such specific outcomes to unfold. Taking this lead, I wanted to investigate how the gold standard produced certain outcomes for the Soviet Union.

Now, what is interesting about the Soviet Union is that the country signed up to the gold standard in the first place. The historiography of the Novaia Ekonomicheskaya Politika (NEP), USSR policies that reintroduced market activities during the 1920s, has often interpreted the Soviet decision to join the gold standard as a very technical matter without a lot of political and social import. In an IPE vein, I saw this as a critical political decision. What were these anti-capitalists and radical revolutionaries doing when they were reconnecting to the key liberal institution that IPE scholars consider foundational to the first wave of capitalist globalization?

Once you have this prism for looking at what the Soviets were doing in the 1920s, you come to realize two things. First of all, one of the most important governing institutions at the time was the People's Commissariat of Finance, which usually doesn't rank high for Soviet historians—partly because they were seen as completing technocratic goals. Second of all, you begin to reconsider what is seen as the Soviets trying to erode the market-based society of the NEP if you look at their anti-speculation campaigns and administrative policies. There are a lot of people who have done very important, detailed work, and the very empiricism of the work shows the ways in which the Soviets were acting administratively. Yet, they don't quite have an explanation for the Soviets' behavior, so those historians fall back on an ideological premise: "That's because they are communists; they are doing this because they hate the market."[1] And sure enough, when you look at it from the vantage point of the history of the gold standard, the Soviets were actually acting ideologically to save the market. That is why they were implementing austerity programs, which did not mean implementing more markets or more capitalism. Rather, its political meaning was to come in administratively to save a particular institution that allowed markets to happen in the first place.[2] They were quite conscious and eloquent about this. It was not subject to some ideological debate, and everyone was on board in saving the gold peg until it was no longer possible with the high levels of unemployment and instability.

KHAN: Another major theme is your focus on autarky. Autarky is often bound up with opposite concepts such as the free market and liberalism. How does your focus on autarky change and contribute to this narrative?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: The assumption of Soviet autarky and my contention that this assumption is wrong are central to my book, and it clearly made some people unhappy. I think there has been a lot of confusion out there as to how to deal with this. Autarky has been foundational as an explanatory model for the Soviet Union as the opposite of whatever is going on in the West. You can only render the Soviet Union anti-capitalist if you can render it as autarkic and as not participating willingly, happily, and ideologically in the exchanges that we associate with capitalism. This is why the book unsettles a lot of explanatory frameworks. I've explained how the Soviets' ideological willingness to engage with the gold standard can change the current explanations for the behavior of the USSR. There is a lot more to be said about what leveling effect doing away with the conception of autarky in the USSR has.

KHAN: Stalin remains a favorite subject for discussion for any Soviet historian. How does he figure in your book?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: Empiricism is important for me, and I was not coming at him with an a priori theoretical understanding. Actually, Stalin didn't figure that much in the book, partly because I didn't have an empirical base to discuss Stalin more extensively. I do, however, document the ways in which Stalin did not have a particular ideological inclination towards autarky. He had to construct a political economy in the context of generalized autarky in the world, which he disliked. In fact, as Michael Dohan proved long ago, in work that should have gotten much more attention and should have been published more extensively, the USSR was the least autarkic country during the 1930s in terms of the volume of trade.[3] The Soviets were pushing trade but the problem was that the value of their trading goods was falling. Money-wise, they seem to become autarkic but they were also pushing against this by promoting exports.

Stalin did this time and again. They were happy to get aid during World War Two, and Stalin felt he had a moral claim to a six billion dollar loan from the United States when the war ended. This is interesting, because if you owe somebody six billion dollars that will create a relationship with you. Stalin was not at all going back to some ideologically autarkic position. When you read Western analysts of the Soviet Union before the Cold War, they expected the Soviet Union to go back to a 1920s position of international market engagement and participation. It was only after the Cold War kicked in that Western analysts began to imagine the Soviet Union as autarkic, against all evidence and all Soviet policy positions.

Additionally, the West is seen to stand for markets when, in fact, it often didn't. Timothy Mitchell's Carbon Democracy shows, for example, how Western corporate and state power were working against the creation of oil markets in the decades after the war.[4] This is the other side of the problem with that binary framework: it does not contend with actually existing capitalism. Markets can be a tool of power. We tend to essentialize markets when we talk about them in the context of the Soviet Union; but, it is difficult to contend that there is something existentially threatening about markets to socialist ideology when they kept popping up.

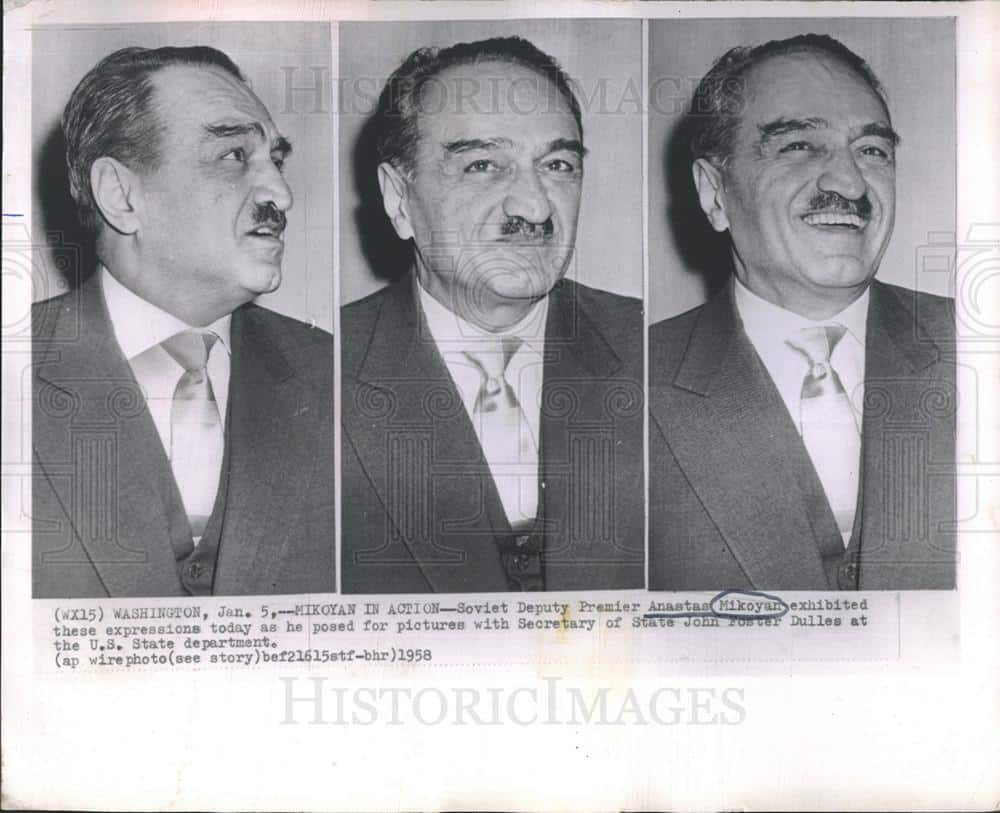

KHAN: There is another figure that many readers will not know, yet he takes a leading role in Soviet financial and economic history: Anastas I. Mikoyan. Why is he important?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: Mikoyan is the protagonist of my story, though I may have romanticized him in my portrayal of him, as one critic pointed out. He was more flexible, more humorous, which partly explains why he was one of the longest-serving Politburo members and the top crisis diplomat under Nikita Khrushchev, and that signals to me a kind of continuity in the Soviet approach to foreign trade. What changed was not so much Soviet positions on trade, but the context within which that trade happened.

The changes throughout Mikoyan's tenure were dramatic. They went from the attempt to reestablish the gold standard, to the Great Depression and generalized autarky, World War Two, and the attempt to institutionalize Bretton Woods, which fails of course in the first decade and a half until the late 1950s. When it finally works you begin to see the creation of capital markets and the lubrication of trade. Mikoyan had a fairly constant ideological approach that needed to adapt to these situations.

KHAN: Having mentioned Timothy Mitchell earlier, did recent literature on the economy not as a trans-historical concept influence your work?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: This is fairly recent work, about two decades old, which reconceptualizes the idea of "the economy" as something that comes into being in the post-war period as a bounded concept and as something that could be manipulated. It was bound up with Keynesianism and the invention of macroeconomics in the 1930s, which occasions this reconceptualization. I try to use a bit of this scholarship of how new concepts of economy and growth came into being at particular moments in time.

I do this because I see that when the Soviets negotiated with Japan, both sides were using the same language, the same discourse of economy,[5] and this seems to me to be more relevant than, say, the Soviet relationship with the Japanese Communist Party. The relationship with Japan was a relationship with its business circles and the political elite, and they established fairly important economic relations. When they thought about Japan, they thought of Japan in those terms, not necessarily of the possibility of the Communist revolution there. When Khrushchev frets about the Soviet Union, the usual parallel he drew was to say: "Look at Japan, they have a tenth of the scientists that we produce and look at how technologically advanced they are. Look at their economic growth." So, Japan occupies a particular space in the Soviet imagination, which is not relentlessly bounded by the Cold War. This is all happening in the context of growing exchanges and at a moment in which the US is losing its commanding control. So it's interesting contextually that changing political conceptions of the economy are also then coming into being. But, this is ultimately the work of intellectual history, and interesting work is coming out of there. I want to tell the story of the power of material exchange, of capital, of institutions, and I am less beholden to the idea that somehow all of this is under the power of ideas. I think ideas are formed dialectically with what is going on materially; ideas become possible as conceptions at certain moments when institutions change and material possibilities change. Having said that, I do think the Soviet Union must play an important role in this emerging literature. I think so because it was the first country to develop such a large volume of statistics and national accounts in the 1930s through which the economy could be conceived. So there is plenty there for the field to work on.

KHAN: The 'Global South' can at times be a new buzzword for historians, rather than a proper historical and sociological concept, and you took notice of it. How did you do so, and what role did debt play in Soviet relations with the Global South?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: I came to the Global South with a critical eye to the Cold War literature as it existed in the early 2000s. At that point, we had a narrative of two superpowers fighting it out in the Global South for influence. This was then taken up and given more nuance by giving the Global South a little more agency, but the story seems to have remained the same in its bipolarity, which scholars maintained through a narrow focus on ideology. From the viewpoint of the Soviet archives, however, you quickly see how little influence the Soviets achieved in these places. The relationship always seemed to be driven by the Global South leaders, who intensified and froze the relations with the Soviets as they liked.

For me, it was interesting to see what was driving this from a Global South perspective. I don't have a very good view, because I never went to those archives, but it is very clear that Soviet documents don't show any preponderant attitude toward the South, in a way that you do have in U.S. archives. When you look at the State Department for example, historical records both strike as racist and preponderant—as if they felt like they had to control and punish Global South leaders. The Soviets didn't have this attitude, not because they were nice people, but because they didn't have the institutions available through which to exercise the stick.

Institutional leverage always remained in the West. It is fairly clear that when regimes fell in what political scientists have called the 'third wave of democratization' in the 1980s, they fell because of an American decision made in the Federal Reserve. They decided to make the US dollar more expensive, and suddenly you had this immense political and social effect throughout the world. The Soviets could never in a million years have had this effect. With respect to how to conceive of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in this episode of the debt crisis, it goes back to the issue of autarky. Because the defining element of the Socialist world is autarky, its end was never meaningfully grafted onto a global history of capitalism, unlike the end of regimes in Latin America, the Philippines, etc. I hope one thing my work has produced is to visualize the Soviet Union as embedded in this larger capitalist story. I think this will be an important avenue of research for new young scholars.

KHAN: On that note, is there any advice that you'd give to students, researchers, and people in general that helped you move forward at points in your work?

SANCHEZ-SIBONY: Well, if I had read political economy for my dissertation, I would have saved myself a lot of grief trying to rush through that literature when I was writing everything up. I would advise everyone to read political economy. [Laughs]

What else? Create the conversations that you want to have. Don't abide by conversations that are limiting your own development. I feel that I spent a lot of time doing so, particularly in the field of Cold War history, where people were perhaps not interested in having particular conversations. I should have known that. I had an advisor, Bruce Cumings, who had tried to bring a political economic approach to the field of Cold War history, and that marked him out as a radical, when all he was doing was bringing orthodox political economy to the field. I should have learned from that. Ultimately, Cumings prevailed in the corners that mattered to producing the kind of narrative that a lot of people have accepted and followed. I hope that that is the fate of what I do as well, but you do that by creating the conversations you want to have and not by knocking on doors that will remain closed.

[1] Julie Hessler, A Social History of Soviet Trade: Trade Policy, Retail Practices, and Consumption, 1917-1953, (Princeton University Press, 2004), Alan M. Ball, Russia's Last Capitalists. The Nepmen, 1921-1929 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

[2] Oscar Sanchez-Sibony, "Global Money and Bolshevik Authority: The NEP as the First Socialist Project," Slavic Review 78, no. 3 (2019): 694-716

[3] Michael Dohan, "Soviet foreign trade in the NEP economy and Soviet industrialization strategy," Ph.D. diss., (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1969). Accessible via https://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/41777.

[4] Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy. Political Power in the Age of Oil. (London and New York: Verso, 2011).

[5] Oscar Sanchez-Sibony, "Economic Growth in the Governance of the Cold War Divide: Mikoyan's Encounter with Japan, Summer 1961," Journal of Cold War Studies 20, no. 2 (2018): 129-154.