What We're Reading: December 2023

Matilde Cazzola, Max Planck Institute for Legal History and Legal Theory.

Emanuele Ertola, Il colonialismo degli italiani: Storia di un’ideologia (Rome: Carocci, 2022)

Emanuele Ertola’s book surveys the set of discourses which, for over a century and amid epochal political transformations (Italy’s unification, two world wars, the rise and fall of the Fascist regime as well as the process of decolonization), supported Italy’s “turn to empire” by shaping a consistent colonial ideology. By presenting their ventures overseas as a necessary response to metropolitan social problems, the Italian political elites developed a violently expansionist imperial narrative which, contra the oblivion that still surrounds Italy’s colonial past in public debates, became key to the country’s national identity. Whereas the history of the Italian colonial empire is the subject of a growing body of excellent scholarship, the intellectual history of its underlying ideology does not seem to have been systematically analysed. This book makes an important contribution in this direction.

Daniel A. Crane, “Fascism and Monopoly”, Michigan Law Review 118, 7 (2020): 1315-1370

Daniel Crane’s article is a fascinating investigation of the connection between industrial concentration and the rise of fascist regimes. By delving into the compelling case study represented by Nazi Germany, the author combines expertise in antitrust and economic regulation with an approach drawing on business and legal histories to demonstrate that the centralization of market power occurred in the Weimar Republic was a crucial factor enabling Adolf Hitler to seize and consolidate a totalitarian authority in the 1930s. The case made by the article about the link between economic monopoly and accumulation of political power is a timely and relevant one in the wake of the growing concentration of the US American economy and the rising scepticism around antitrust enforcement.

This book contributes to the growing body of scholarship on the interpenetration between British imperial domination and humanitarian policies by contextualizing the life and career of Dr Thomas Hodgkin (1798-1866) within the British philanthropic activism of the middle decades of the nineteenth century. More particularly, the author pays special attention to Hodgkin’s views on settler colonialism and the “protection” of Indigenous peoples in the Australian colonies and at the Cape. Importantly, by assessing the role of a lesser-known yet important figure within the context of the nineteenth-century British imperial developments and shedding light on his connections with prominent metropolitan empire-builders and colonial governors, the book interrogates whether imperial policies can be really both colonialist and “humane”.

Antoney Bell, McGill University.

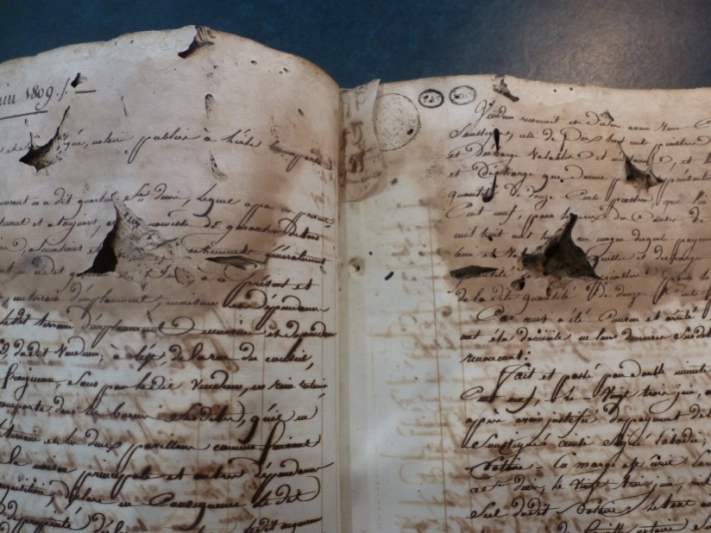

A recent monograph on Indian Ocean slavery uses the study of a woman who was sold into slavery in India, and the struggles of her children to gain freedom in the French Mascarenes. Acting as a microhistory and prosopography, Peabody writes a multigenerational narrative about slavery and emancipation after her ten-year expedition in the national archives of Mauritius, Reunion, Paris, Aix-en-Provence, and London. The strength of Madeleine’s children lies in her narration of Madeleine’s son Furcy, who is well-known in Réunion for contesting the illegality of his enslavement in the high courts of Paris. Peabody further argues that Furcy fought the colonial government and planter class because he was seeking to obtain his rights as a patriarchal bourgeois citizen who could marry, own slaves, and acquire colonial land.

Jennifer Spear’s work has been integral to the scholarship on the early formation of Louisiana as a French and Spanish colony. Spear demonstrates that “race was treated by early Americans as one obstacle among other everyday realities around which they negotiated their lives” (Spears, 14). Her monograph provides an important understanding of how French laws of blood purity worked to restrict racially exogamous relationships in New Orleans. Using official correspondences, court records, church registers, and wills, Spear examines the codification of laws and restrictions on sexual relationships across racial barriers with the intent to preserve the racial order of French Louisiana.

Asensio Robles López, EUI, History Department.

It is difficult to add anything new to what other scholars have already said about this book. And perhaps that is precisely the perfect place to start. Fritz Bartel's The Triumph of Broken Promises has been a worldwide success since it saw the light of day in 2022. And for good reason: early praise for this book (formerly Bartel's Ph.D. dissertation, winner of the 2018 Oxford University Press USA Dissertation Prize in International History from the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations) and Bartel's ambitious thematic scope suggested that this work had the potential to immediately become a major contribution to the fields of Cold War studies and the history of capitalism.

And an impressive book it is. Though this might not be the best place for a thorough appraisal of Bartel’s book, a few notes on why it has garnered so much attention over the last months are worth exploring. The Triumph of Broken Promises, as its own subtitle suggests, sets to explain the end of the Cold War in the light of the history of capitalism. In many respects, this is nothing new in the Cold War historiography. Other historians (though not many) have devoted liters of ink to explaining how growing economic hardship within the Eastern Bloc, as a result of its growing economic interdependence with the West, proved crucial to the later collapse of its authoritarian regimes. But Bartel successfully finds his own niche within this literature by extending this same narrative to also the Western bloc. It was not simply the Eastern European countries that went through horrible balance of payments and inflation problems. These were the very same bugbears that haunted the West throughout much of the 1970s and early 1980s. Britain’s Winter of Discontent and Poland’s crisis around 1980 are, in many ways, two different phenomena with very similar underlying problems.

However, Bartel argues, it is precisely here that the ideological differences between capitalism and socialism mattered the most. If similar crises on both sides of the Iron Wall did not produce the same results (namely, the dissolution of the established political order), it was because the West had the tools to undertake painful economic reforms in the face of globalization, while the East did not. Liberalism and democracy are two key concepts here. The fact that governments like Thatcher’s were backed at the ballot by ample majorities was essential to the legitimization of the economic transformations that Western economies had to undergo during the 1980s. As was the fact that Western policymakers could ward off domestic criticism by pointing to global market forces and the need to better follow its needs. In other words, Western policymakers could advance tough economic agendas without putting into question the fundamental principles that supported their systems. It is here that neoliberalism plays a central role: figures like Thatcher or Reagan could easily argue that it was not capitalism that was in crisis, but rather Keynesianism.

In the end, there is nothing triumphalist in this argument, and probably here lies one of the many strengths of Batel’s work. If the West prevailed while the East perished, it was because the West had the tools to break their old promises of sustained economic prosperity in the face of an increasingly globalized world.

It was the right time to return to Charles Maier's classic 2000 article for The American Historical Review. Maier's new book, The Project State and Its Rivals. A New History of the Twentieth Century (Harvard University Press, 2023) seems to be the final fulfillment of Maier's promise in that article to turn some of the ideas presented there into a monograph. Revisiting this piece is therefore the perfect introduction to Maier's new work. It will be an exciting experience to discover what ideas he has focused on and what has changed. Twenty-three years in passing is, after all, a very long time.

There are two specific points that make Maier's article interesting from a global history perspective: it seeks to offer a less Western-centric interpretation of the twentieth century and to recognize the transformative power of globalization in contemporary societies. Twentieth-century histories, Maier argues, have tended to revolve around what he calls “moral histories”: narratives that either juxtapose forces of progress and regression (e.g., democracy versus authoritarianism) or focus on moral atrocities (the Holocaust) and their chastening effects. While not underestimating the value of such narratives, Maier rightly points out their limited value in engaging non-Western societies. Nor do they address, he adds, some of the most transformative forces that have shaped societies in recent decades. To compensate, he offers an alternative reading of the “long twentieth century” (beginning around the 1860s and fading out somewhere in the last three decades of the next century) that centers on territoriality.

Interestingly—and this may be one of the main differences between this article and his new book—Maier refuses to see “territoriality” as synonymous with the process of nation-state formation. For Maier, territoriality refers to a particular way in which humans conceive of space; one that involves a more aggressive (re)definition of borders, a more intense exploitation of the resources within, and a stronger connection between the space within and the political/social/juridical authorities that claim sovereignty over it.

Needless to say, there is much more nuance to Maier’s arguments than can be covered in this small section. Suffice it to say, in conclusion, that Maier's article has become a classic because of the way in which his proposed narrative of territoriality manages to interweave stories as diverse as those of the American Civil War, Meiji Japan, the unification of Italy and Germany, or the state-building processes in Canada, Mexico, Argentina, or Thailand. What remains to be seen—and Maier's new book may be particularly revealing in this regard—is the extent to which twentieth-century territoriality will continue to play a prominent role in the new century. This is not an easy question, as Maier reminds us: "The issue, however, is not, as often claimed, whether states must decline in the age of globalization. No such claim is made here. The question is to what degree political jurisdictions can use the resources of territoriality to assure economic security—and that cannot be answered either by counting states or citing their legislative conferences." (Maier, 825)