INTERVIEW—Toynbee Coronavirus Series: Dipesh Chakrabarty on zoonotic pathogens, human life, and pandemic in the age of the Anthropocene

Living through historically unprecedented times has strengthened the Toynbee Prize Foundation's commitment to thinking globally about history and to representing that perspective in the public sphere. In this multimedia series on the covid-19 pandemic, we will be bringing global history to bear in thinking through the raging coronavirus and the range of social, intellectual, economic, political, and scientific crises triggered and aggravated by it.

Toynbee Coronavirus Series—A global historical view of the coronavirus pandemic

Interview with Dipesh Chakrabarty

Toynbee Prize Awardee Dipesh Chakrabarty is the Lawrence A. Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor of History, South Asian Languages and Civilizations, and the College at University of Chicago. He is a founding member of the editorial collective of Subaltern Studies, a consulting editor of Critical Inquiry, a founding editor of Postcolonial Studies, and has served on the editorial boards of the American Historical Review and Public Culture, among others. His distinctions, publications, and awards are too numerous to mention; the landmark work for which he is perhaps best known, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, 2000; second edition, 2008), has been translated into Italian, French, Polish, Spanish Turkish, and Korean and is being brought out in Chinese. Included among his vast range of research interests are the implications of climate change science for historical and political thought and, most relevant for our discussion today, the Anthropocene.

How may we situate the pandemic within the discourse or politics of the Anthropocene? Does the pandemic shift the discourse in any way or reveal new possibilities for human change or progress?

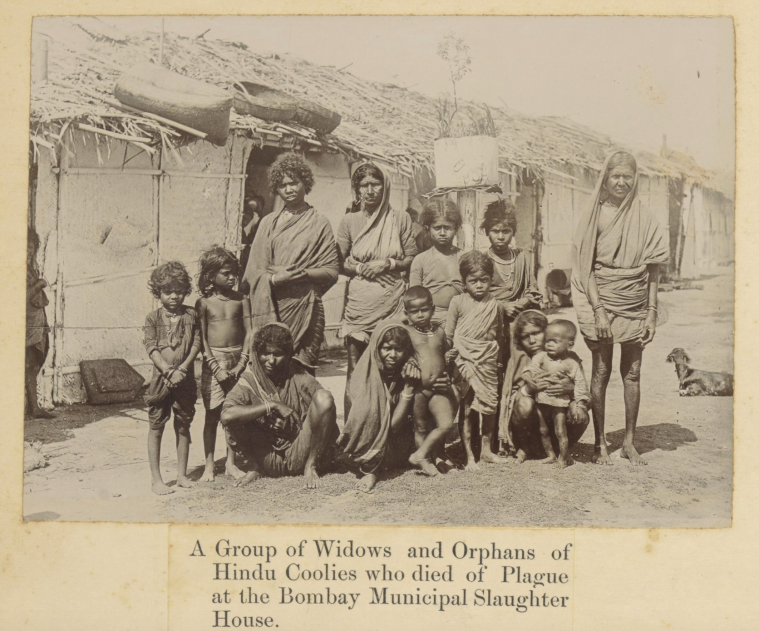

The pandemic is indeed connected to the period in global history that Earth system scientists and their collaborators have designated “The Great Acceleration”—c.1950 to now. But it surely caught humanity by surprise, unlike, say, the deadly typhoons, landslides, or firestorms that we have now come to expect from everything we know about the deleterious effects of anthropogenic global warming. Yet, the moment the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 to be a pandemic, United Nations (UN) officials in their section on Environment immediately drew a connection between deforestation, destruction of wildlife habitat, growing human affluence, and the pandemic. Some of them even went so far as to describe the pandemic as nature’s “warning” to humans. They pointed out—and others have too—that in the last twenty or so years, seventy-five per cent of the new infectious diseases for humans have been of the zoonotic kind, i.e. they originated when a virus or bacteria jumped species, moving from wild animals to humans. This movement of viruses and bacteria from animal or bird bodies to humans has been hastened by the destruction of wildlife habitat, thanks to the increasing pace of deforestation due to mining, logging, road building, conversion of forests to farmland, expansion of human habitations, illegal trade in wildlife products, and so on. These propositions are also supported by the research of virologists like Nathan Wolfe (see his book, The Viral Storm) and science writers such as David Quammen (the author of Spillover). The chain of causation shows the connection between the Anthropocene and the pandemic: increased access to cheap and plentiful energy leads to greater human numbers and prosperity that in turn results in increasing human demands for development and consumption and thus, finally, to the destruction of wildlife habitat and an increase in the interface between humans and wild animals. All these fit nicely, if sadly, into the narrative of Great Acceleration that underpins the Anthropocene hypothesis.

In response to the second part of the question: Not sure about progress, but the pandemic has shown us many things among which the following stand out: (a) it has made visible in many places how, when humans are forced to scale back their presence and activities, the air becomes cleaner, the sky is bluer, and cities get back some of the birds and animals that they may have lost; (b) that we may be ready to inhabit a world with less travel and more online presences; (c) that a world based on so much travel actually leaves us vulnerable to future pandemics of this kind; (d) that humans are the biggest spoilers of this planet’s environment.

This movement of viruses and bacteria from animal or bird bodies to humans has been hastened by the destruction of wildlife habitat, thanks to the increasing pace of deforestation due to mining, logging, road building, conversion of forests to farmland, expansion of human habitations, illegal trade in wildlife products, and so on.

How must political-economic thought and institutions change to accommodate the normative or practical challenges that the pandemic has raised?

For one thing—and assuming that global leaders of the economy are not going to mend their ways, at least in the short run—it produces an immediate need for creating global institutions for predicting, if possible, the emergence of future pandemics and for overseeing their global management. Some economists have also suggested the launching of an International Solidarity Fund that will make it possible for the richer nations of the world to help poorer nations deal better with the devastating impact of pandemics on their economies, so that the poor of the world are not forced to make a horrible choice between dying of hunger and dying from the pandemic. As the pandemic recedes, as it inevitably will, it may also present us with a moment when a global carbon tax could be introduced, in order to preserve the benefits of the enforced lowering of greenhouse gas emissions during the shutdown period. This may also be the time to take seriously the kind of proposals that Edward O. Wilson makes in his book Half-Earth for the preservation of global biodiversity.

What geopolitical histories should be brought to bear in thinking through this moment in South Asia?

I have wished for a long time that the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) would evolve into a European Union-like formation with free flows of capital, labor, ideas, and people across the boundaries of the nations that constitute the SAARC. This would, of course, require nations to get over the mistrust and suspicion that for all too long have characterized their relationships. But this seems to be the only way India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, for instance, can forget the trauma of the 1947 Partition and lasting—well, at least, longer-lasting—peace may be achieved in Kashmir. This would allow the region to deal better with the various impacts of climate change including coastal cyclones. Also, China needs to be part of this conversation. The glaciers of the Himalayas feed the river systems of several Asian countries, from Pakistan to Vietnam. Yet there is no multilateral treaties or organization to look after these glaciers. Every country thinks of rivers passing through its territory as its own resources. Overall, I think that this region ought to think of itself as a region and to create policies, shared funds, and authorities to deal with climate change, water scarcity, cyclones, tsunamis and other “natural” disasters.

How do you read the media/health policy focus on the individual body vs. the body politic in South Asia? How may we situate that focus within your region's history of political thought?

One of the saddest sights coming out of India during this pandemic has been the condition of the so-called “migrant workers.” When the country was shutdown with only four hours’ notice, these workers lost their income and were thrown out of their residences by landlords/slumlords unwilling to let them stay for free. The workers then suffered for months untold number of indignities and harassment. Many died on the desperate journey back “home.” The pandemic revealed an open secret about Indian labor force: that in a country where around ninety per cent of its laborers are engaged in the informal sector, the first fact about these laborers’ lives is the fact of migrancy. We all knew this but no one ever—at least in the policy-making circles—seems to have given it a conscious thought. All the glitter of upper-middle-class and upper-class India rests on the labor of these migrants.

Apart from that, there are the problems of undertesting and, hence, likely underreporting of the incidence of COVID-19 across nations in South Asia. The demographic factors—a largely young and largely rural population—go in the region’s favor. But the requirement of physical distancing is very hard to enforce or practice in a region where lives are lived in an intensely social fashion, not simply because cities are crowded—that is a problem, of course—but also by cultural choice.

Then there is the prevalence of poverty and relative ignorance of medical knowledge among the citizenry. These subaltern classes are usually the forgotten members of the body politic. Yet helping them to deal with the pandemic is critical to the region’s success in managing it. I think that is the crucial task facing the administration in the region. But the task is complicated, in the case of India, by the problems of the country’s federal political structure.

The pandemic revealed an open secret about Indian labor force: that in a country where around ninety per cent of its laborers are engaged in the informal sector, the first fact about these laborers’ lives is the fact of migrancy. We all knew this but no one ever—at least in the policy-making circles—seems to have given it a conscious thought. All the glitter of upper-middle-class and upper-class India rests on the labor of these migrants.

What does our current moment look if seen from the viewpoint of zoonotic pathogens?

What questions should we be asking that we aren’t yet?

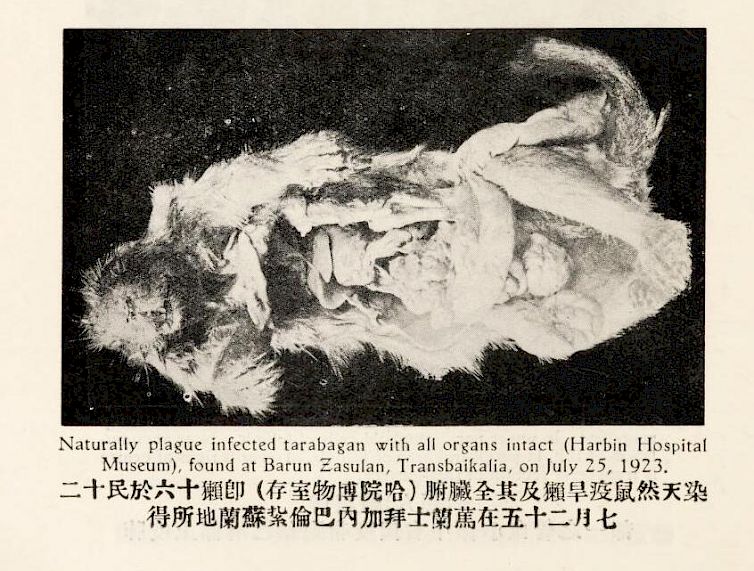

Let me tackle these questions together since, for me, they are connected. The current moment belongs not only to the global history of humans, it also represents a moment in the history of biological life on this planet when humans are acting as the amplifiers of a virus whose host reservoir may have been some bats in China for millions of years. Bats are an old species, they have been around for about fifty million years (compared to our 300,000). In the Darwinian history of life, all forms of life seek to increase their chances of survival. The Novel Coronavirus has, thanks to the demand for exotic meat in China, jumped species and has now found a wonderful agent in humans that allows it spread world-wide. Why? Because humans, very social creatures, now exist in very large numbers on a planet that is crowded with them with most of them being extremely mobile. That, in short, is the history of our globalization. And, of course, the virus is helped tremendously by the fact that people can be infectious before they are symptomatic. So from the point of view of the pathogen, this has been a great move. Humans may win their battle against the virus—I really hope they do—but the virus has already won the war. This is no doubt an episode in the Darwinian history of life. And the changes it causes will be momentous both in our global history and in the planetary history of biological life.

The current moment belongs not only to the global history of humans, it also represents a moment in the history of biological life on this planet when humans are acting as the amplifiers of a virus whose host reservoir may have been some bats in China for millions of years. Bats are an old species, they have been around for about fifty million years (compared to our 300,000). In the Darwinian history of life, all forms of life seek to increase their chances of survival. The Novel Coronavirus has, thanks to the demand for exotic meat in China, jumped species and has now found a wonderful agent in humans that allows it spread world-wide. Why? Because humans, very social creatures, now exist in very large numbers on a planet that is crowded with them with most of them being extremely mobile. That, in short, is the history of our globalization.

The really critical and fundamental question we have to ask is: do we, as humans, want to continue expanding an economy that keeps increasing for us the risk of zoonotic diseases? Nathan Wolfe, the virologist I mentioned before, suggests that epidemics caused by viral and bacterial transfer between humans and domesticated animals reached a kind of equilibrium about 5,000 years ago. He says that most recent infections with the potential to cause epidemic or pandemic diseases have been due to increasing human contact with wild animals. Wild animals do not seek us out; we go and destroy their habitat, forcing them to come into contact with us. Many Earth system scientists, evolutionary biologists, and Anthropocene scholars have been reminding us that the global economy is destroying bio-diversity and that, on human scales of time, biodiversity is a non-renewable resource that is critical to the flourishing of all life, including ours. It is time we debated the kind of civilization humans would want to live in. The Cold War battle between capitalism and socialism is well and truly dead. But that does not mean that the question of debating capitalism has lost any of its importance. The alternative to present-day capitalism does not have to be Maoist or Leninist socialism. How to remain modern and democratic and yet not destroy or completely dominate the order of life on the planet remains a critical question as humans contemplate their future of a planet they have taken for granted for far too long.