Empire of the Air, Empire of the Earth: American History in a Global Context with Jenifer van Vleck

Scan through recent headlines, and it will quickly become clear how much modern societies and international politics revolve around the airplane. During the ongoing Ebola crisis, national health authorities–even those for countries whose flag carriers didn't run direct flights to West Africa–have panicked over the possibility of a rogue infected passenger contemning whole countries during a fluke layover. Meanwhile, the American military continues to conduct its counter-terrorism policy in Central Asia and the Middle East in large part through strikes from drones. Try boarding an airplane bound to the United States with stamps from countries in those regions in your passport, and it's likely that your ticket will be stamped with a mysterious "SSSS"–a sign that you've been singled out as a security risk, a putative airborne threat that has to be scanned before even boarding a flight from, say, Frankfurt to the United States. Whether governments today think about protecting the nation at home (as with Ebola) or abroad (air strikes as foreign policy), it's clear that our notions of security have become linked with a logic of the air that goes beyond the boundaries of the nation-state.

It all seems like a far cry from the supposed heyday of air travel–glamorous flight attendants, supersonic travel, and the possibility of a seamlessly connected world that a look at the departures board from a major airport today can still awaken. But even if the structures of airspace in the early 21st century invoke more pessimism than inspiration, it bears asking how things got so bad in the first place. It demands, in short, history. Visions of what how travel through the skies could be–and the relationship of states and empires to the air–have a deep history that demands scrutinizing. Indeed, with airline alliances touting themselves as "One World," it's especially worthwhile for scholars interested in global history to do that kind of work.

Fortunately, our latest interviewee for the Global History Forum, Jenifer Van Vleck, explains much of this back story in her recent Empire of the Air: Aviation and the American Ascendancy, published recently by Harvard University Press. Van Vleck, an Assistant Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University, devoted years to scouring through the archives of Pan American World Airways (Pan Am) and numerous government and Presidential Archives to tell the story of a corporation–and an industry–that reveals much about the shape of American corporate globalism and American empire. The Global History Forum was delighted to sit down with her this summer to discuss her intellectual journey, Empire of the Air, and her upcoming work in the history of technology and American foreign relations.

•

It would be easy to see the seeds for Empire of the Air in Van Vleck's hometown, Dayton, Ohio. Dayton, located in southwestern Ohio, might be quintessential flyover country even for many Americans, but if it is, that's ironic, since Dayton remains the birthplace of–and a hub for–American aviation. Orville and Wilbur Wright, the inventors and builders of the world's first successful airplane, hailed from the area, and today no small part of Dayton's economy derives from the presence of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, the largest base of the United States Air Force. (The Dayton Accords, the peace agreement that created the structure of contemporary Bosnia-Herzegovina were signed there–fitting for a war in which aerial strikes played such an important role).

Yet while growing up, Van Vleck struggled to see why, exactly, people were so interested in Dayton or the city's history of aviation. Grade school and secondary school meant an annual tradition of being dragged to the National Museum of the US Air Force, and when relatives came to visit, the museum often featured in the agenda. Some of the museum's attractions–items relating to outer space–interested, but in general, the history of aviation seemed to revolve around uncritical enthusiasts' accounts and highly technical histories of airplanes themselves. As Van Vleck departed for Rhode Island to pursue her undergraduate education at Brown, where she studied American social, cultural, and gender history, a history that seemed to portray the machines themselves as history's real actors held limited appeal. Writing the history of technology seemed unlikely, even as –as the Internet economy of the late 1990s and early 2000s boomed–Van Vleck took a job at a technology company in New York's "Silicon Alley."

But it was in the climate of early 2000s-New York that Van Vleck began to think more about writing history. The first .com boom may best be remembered for Pets.com ads and overnight millionaires in Silicon Valley, but beyond the half-baked business models and gold rushes, that boom also relied on and generated a certain amount of naïve optimism about the power of technology to change societies. The Internet, it was said, was supposed to usher in democracy, freedom, and openness. Overnight, this ideology held (and still holds in some quarters), schoolgirls in Afghanistan will be able to attend online courses and realize their dreams; armies of smartphone-using Iranians will mobilize themselves to overthrow the Islamic Republic and usher in a world of free markets and enlightened democracy. Looking back on her days at the museum in Dayton, Van Vleck saw deep similarities between the discourses of freedom attached to new technologies in the United States–then the airplane, in the early 2000s, the Internet. Perhaps it would be worthwhile to probe the comparisons more deeply?

Events of a darker sort helped her make a decision. By the summer of 2001, cracks had emerged in the fabled New Economy, and the utopians (and millionaires) of yesterday saw their hopes (and riches) vanish. But on a Tuesday morning in September, Van Vleck awoke along with millions others living in New York to see two planes crash into the World Trade Center. As the towers collapsed, and thousands died, the technological optimism of only a few months ago seemed hollow. Rather than marking time in the tech sector, Van Vleck wanted to do something more meaningful.

Van Vleck applied to the History program at Yale, thinking that she would pick up (roughly) where she had left off at Brown, working on American cultural history. But Van Vleck had the fortune of arriving in New Haven at a time when the literature on transnationalism, modernization and technology was booming–think of books like Michael Adas' Dominance by Design or Jeffrey Engel's Cold War at 30,000 Feet–and her seminars with teachers like Seth Fein (now at Columbia) reflected that fact.

But the topic for her dissertation–and book–came by surprise. Taking a course with her adviser, Jean-Christophe Agnew, on the concept of Pan-Americanism, Van Vleck (having just watched Catch Me If You Can, by her own confession) came to wonder: why was it that the American aviation giant Pan Am had "Pan-American" as its name, when its network stretched around the world? Van Vleck began investigating the history of the company, whose roots lie in the government mail business in Central America in the 1930s, and ended up writing an entire dissertation on the topic.

Since beginning a position as an assistant professor at her alma mater in 2010, alongside her teaching duties and publishing a few articles, Van Vleck re-wrote the dissertation into a book. Empire of the Air, the result of all of that labor, traces the career of American aviation and the politics of the air itself from an American perspective. The book's early chapters trace the "Americanization of the airplane," showing how aviation came to be viewed as an area of especially American dominance. Ironically, given the invention of the airplane by the Wright Brothers, readers might be surprised to learn how relatively backwards the American aviation industry was during the first third of the twentieth century. European powers poured far more money into their aviation industries, whether to help them conduct colonial wars (as did Italy whilst carving up the territory that now comprises Libya) or during the First World War. All the same, the US military investigated the possibility of around-the-world flights; the US Congress, meanwhile, passed the Air Mail Act in 1925, allowing the Post Office to contract with commercial carriers to carry mail. When Charles Lindbergh crossed the Atlantic flying solo in 1927, it seemed to hearken the dawn of a new American age of aviation.

Lindbergh-mania did indeed sweep the United States, but just as important for the fate of American aviation was the uptick in the use of "commercial aviation as a chosen instrument of foreign policy," particularly in Latin America, the theater of the second chapter of Empire of the Air. With the Mexican government threatening to nationalize its oil supplies and the Soviet Union opening an Embassy in Mexico City, government élites felt threatened by a nationalist and statist resurgence in their backyard. Charles Lindbergh, ever useful as a double symbol of international fame and American whiteness, flew to Mexico for a goodwill tour, where he was celebrated by crowds. But Lindbergh's Latin American tour continued from there, both to scout out potential postal routes and to survey the potential routes of attack on the Panama Canal. This was no trivial worry: German-run airlines had established a foothold in Latin American markets during the 1920s, and the Reich had attempted to convince Mexico to enter the Great War against the United States in 1917.

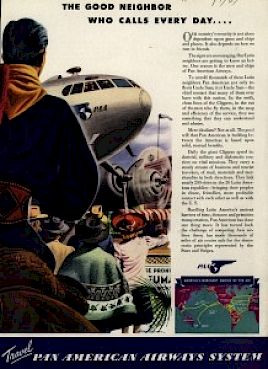

To combat the threat, a new airline, Pan-American Airways, was founded (first by US Army Air Corps officers, then run by Juan Trippe, a former aviator and well-connected member of the WASP élite in spite of his last name). Thanks to the Air Mail Act, Pan Am was subsidized so heavily as to dominate the air infrastructure of Latin American states; it demanded a monopoly on all mail transportation to and from the United States, free use of national infrastructure, and other benefits from Guatemala, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Colombia, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, and Venezuela throughout the 1930s. It was a fitting form of corporate imperialism for FDR's Good Neighbor policy. Rather than occupying countries (as the US had in Nicaragua from 1912-1933), Washington would instead pursue a more subtle form of hegemony towards its southern neighbors. Pan Am, as it came to be called, grew and grew, encouraging tourism and other benign forms of engagement between the United States and Latin American partners. Pan Am didn't stop at Latin America, however. Trippe was long obsessed with the construction of a global air network, and in the mid-1930s the airline expanded to Manila (then a US colony), Hong Kong, the Azores, Marseille, and Southampton, subsidized all the way by generous (often illegally so) mail rates.

But it was the Second World War that really changed the face of American aviation. As the Luftwaffe scored impressive victories in the European theater and launched the Blitz against the British, the need for a robust national aviation industry became ever more obvious. FDR demanded that the US manufacture 50,000 planes a year, and with total mobilization of the workforce, the American economy soon produced "more than twice as many planes annually as had been built in the United States in the thirty-six years between the Wright brothers' first flight and the beginning of the war." Army service and subsidized flight schools trained hundreds of thousands of new pilots, turning the United States into a huge industrial reservoir for the British Empire & the Soviet Union through Lend-Lease and, later. During the Pacific War, too, the aerial "discovery" of the Pacific pioneered by Trippe and the military less than a decade before gave American forces an advantage in their war against the Japanese Empire.

Little surprise, then, that throughout the 1940s, new visions of what the airplane age–and an airborne America–would mean for the future were rampant. As part of a national solidarity campaign, FDR sent his opponent in the 1940 Presidential campaign, Wendell Willkie, on a round-the-world publicity campaign to various Allied nations. Writes Van Vleck: "Marveling that his global voyage had required just 160 hours aloft, Willkie envisioned 'a network of airlines connecting the nations.'"

Yet Willkie's vision of some kind of global airline service–vaguely realized today perhaps only through the United Nations Humanitarian Air Service–never took off. Henry Luce, meanwhile, promoted a view of muscular American leadership in the pages of Life magazine. Viewing the world through the lens of the airplane, Luce's writers argued, changed one's perception of America's possibilities. On a Mercator map, America seemed far removed from exotic theaters like the Far East or the Middle East. But azimuthal representations of the Earth, depicting "great circle" routes that accurately traced airlines' actual routes, showed how in an aviation age the USA was actually quite close to Russia or northern Europe. "We are a country living next door to the world," explained one article. "Our former vacuum of insulating space has been filled, literally, by air and airplanes."

Such visions made for nice copy, but the realities of war and, later, the assumption of much of Britain's interwar empire, proved more decisive for American aviation's future. With German airplanes pounding Britain for much of the early 1940s and the British struggling to run combat operations from North Africa to the Indian Ocean, the Royal Air Force's logistics were stretched thin during the war. Supply chains that connected British colonies in Sub-Saharan Africa with the front in North Africa were especially difficult to man given the pressing needs on other fronts.

Here Pan Am stepped in once more. Lend-Lease was creatively interpreted in such a way that authorized the airline to begin transporting American supplies–via Florida and Brazil–to British West Africa and independent Liberia. From there, the airline transported the supplies to Khartoum, Cairo, Asmara, and Aden–a fantastic logistical spine running from Miami to Cairo by way of Belem. The planes went on from there transporting more materiel to Iran and India, a vast empire that expanded Pan Am's global reach. Pan Am also refurbished many of the air bases it ran flights from.

The operation was relatively short-lived–August 1941 to November 1942, when the U.S. Army Air Forces took over the logistics, assuaging British concerns that Pan Am intended to dominate post-war African aviation. But the episode arguably marked a high-water point for American corporate globalism, with a private company being used as an indirect extension of American foreign policy. As the fifth and sixth chapters of the book demonstrates, moreover, foreign competitors were not always at east with the American "empire of the air." At post-war international aviation conferences, British politicians were keen to maintain an international regime of imperial preferences as the key feature of aviation regulation. American airlines, much less their French or even Soviet counterparts, did not have an inherent freedom to land at airports in, for example, Kenya. Such a territorial policy, however, meant trouble for an empire like the United States, which lay far away from strategic points in Eurasia. Imperial preference meant that the British would maintain crucial nodes such as Aden or Singapore, with American carriers left to the whimsy of European powers.

Countering this view were American liberal internationalists like Adolf Berle, the Chair of an Interdepartmental Committee on International Aviation created in January 1943. As Berle and other experts prepared for a series of international aviation conferences in London and Chicago, they argued for what became known as the Open Skies doctrine–the idea that aviation demanded a series of "freedoms" that included the right to fly over other countries' territory, conduct international routes (i.e. New York to London), and, crucially, "the freedom to pick up and discharge traffic at intermediate points." Given the effort that Pan Am had invested into creating a logistics empire, the last point was especially important: in a pre-jet age where planes had much more limited range than a Dreamliner or A380 today, the ability (for example) for Pan Am to conduct its New York to Delhi service via London was critical.

But even as Berle and others rallied nations against the British system of imperial preference, there was almost no international consensus on the Fifth Freedom. By July 1946, the United States itself disengaged from the conventions, instead choosing to sign bilateral agreements with partner countries. That's partly why Fifth Freedom flights (like Emirates' service from New York to Dubai … via Milan) remain uncommon today as part of an international regime and largely restricted to nation-to-nation deals: small, remote New Zealand allows Emirates to run Fifth Freedom routes that run through Australia in order to give its businessmen more route selection at all.

Throughout, of course, there was another regime of international aviation threatening the passover of power from one Anglophone hegemon to another: the Soviet Union. Moscow had not participated at the Chicago conference, and as the Cold War began, American policymakers fretted over Soviet penetration into crucial Third World theaters. The fact that it was Aeroflot (later to become the world's biggest airline) that first introduced jet airliners into service threatened Pan Am and American corporate globalism further. In theory, the Soviet Union could do to all of Eurasia what 1930s-era Pan Am had done to Latin American markets. In response, Pan Am joined forced with American aid agencies to build up national carriers in developing countries–notably, as Van Vleck shows in Empire of the Air and a related article, in Afghanistan, where Pan Am helped launch Ariana Afghan Airlines.

The Aeroflot threat turned out to be overhyped, though. The Soviet airline still managed to use airports in Ireland and Newfoundland as pit stops to enter the Caribbean and Latin American markets. And in the 1970s, Aeroflot exploited Soviet-era "fifth freedom" agreements to ran some of aviation history's most curious flight stretches: Cairo-Khartoum-Entebbe-Dar es Salaam, for example. (Global History Forum readers may be interested to know that Stephen E. Harris at the University of Mary Washington is currently writing a history of Aeroflot.)

But the late 1960s and early 1970s were the halcyon days of Pan Am both as business empire and cultural icon. At its peak, based out of the Pan Am Building in Midtown Manhattan, Pan Am flew to 86 countries on every continent, served haute cuisine from Maxim's in Paris on select first class routes, and embedded itself in America's cultural consciousness, if the television series Pan Am is any sign. Cheap oil prices helped keep Pam Am profitable, and when the chance came to purchase the new Boeing 747, Pan Am invested big, eventually operating dozens of the jumbo jet.

As Empire of the Air concludes, however, it was at this moment of seeming invincibility that the seeds for Pan Am's demise were sewn. Juan Trippe retired as CEO in 1968, after forty-one years at the helm of the corporation. The average tenure of Pan Am's subsequent CEO's was less than ten years, as the company struggled to find direction. Higher oil prices were a major handicap for future growth, but perhaps just as important was the changing model of American corporate globalism and the regulatory models said attitude fostered. While Pan Am was the United States' flag carrier, antitrust regulations forbade it from merging with major domestic carriers like Eastern Airways, National, or Delta.

That, in turn, made it difficult to feed domestic passengers into the company's select international hubs for flights further afield. Now, smaller "national" carriers could focus on feeding their passengers into one hub for flights to, say, London. Further, since other countries often allowed such quasi-monopolistic positions, the passenger traveling from, say, New York to Hamburg might well prefer to fly Lufthansa the entire way on one ticket. All of this meant that Pan Am's fuel-guzzling 747s were flying half-empty. Pan Am tried to acquire East Coast shuttle services to feed more passengers to JFK and Miami, but airline deregulation in 1978 only increased Pan Am's competition domestically.

Dramatic acts of terrorism like the Lockerbie Bombing in December 1988 further hurt Pan Am, but the real shift that Empire of the Air highlights is that in the form that American corporate internationalism took throughout the 20th century. As the American empire took shape in the mid-20th century, it was common sense that the government ought to subsidize–even over-subsidize–select corporations for strategic reasons. No matter how electrifying the appeal of pure market competition might seem, the security of the Panama Canal, of Nazi domination of Europe, of Soviet domination of Eurasia all proved decisive arguments for supporting a behemoth like Pan Am. Markets, it turned out, weren't a given; they were made by the nations regulatory environments that geopolitics and grand strategy dictated.

Only as a market revolution took sway in the United States (although it bears mentioning that it was Jimmy Carter who authorized airline deregulation) did a new paradigm take shape. America's "empire of the air" would be financed through private corporations less dependent on the state than Pan Am, although still granted the legal framework to declare bankruptcy, furlough "redundant" workers, and cut service to "non-core" markets inside of the United States. These shifts helped doom Pan Am, all while delivering Americans far less expensive international travel than their parents or grandparents had ever known. Still, as competition forces airlines to merge again and again, it remains an open question whether the logic of deregulation will only eventually lead to monopolies and the loss of services to rural America–unless, that is, Emirates has the benevolence to stop there en route to Dubai.

•

Having put aside Empire of the Air, Van Vleck has been engaged with a new project that she hopes will push forward the discussion on corporate globalism. Reading through the copy of Henry Luce's mid-century magazines, she explains, she came across a piece titled "The Earth Movers" about a company she had never heard of, Morrison-Knudsen. Googling revealed a picture of a huge civil engineering empire, based in Idaho, that ran dozens of complex engineering projects for the American empire at home and abroad. In southern Afghanistan, Morrison-Knudsen (MK) was contracted by the Royal Government of Afghanistan to build canals for resettlement projects; it built dams all over the world; military bases in the Pacific and, later, Vietnam; it built railcars, missile silos, and subway cars for major American cities.

Van Vleck was intrigued. Scholars might talk about "American empire" in a vague, abstract sense, as if "American imperialism" was a miasmic invisible force, but it struck her that writing "history from the middle"–actually dealing with the material, built culture of America at its imperial peak–could help bring some clarity to the subject. After a series of archival trips (and, no doubt, too many layovers at hubs in Denver, San Francisco, and Chicago while waiting for a connecting flight), Van Vleck saw the outlines of the project: a history of private civil engineering contractors in the making of American development at home and abroad.

The project, tentatively titled Ambassadors with Bulldozers, promises to expand on the themes that Van Vleck explores in Empire of the Air. Firstly, a focused study of MK and other firms like Kellogg, Brown and Root shows that American empire had multiple geographic origins. The Pan Am story may have begun in Latin America, but the firms that went on to build dams in Afghanistan and, later, build military bases in Diego Garcia, Iraq, and … Afghanistan often had their roots at home, in the American West. During the early 20th century, federal dollars helped fuel companies like MK as they conducted complex land improvement and irrigation projects. Transforming the American West frequently led to a virtuous cycle of federal dollars devoted to terraforming making Western cities potential hubs for the defense industry; when American military power went abroad, the earth movers followed.

Secondly, these different origins produced a different geography of American corporate power than the Pan Am story hints at. Where Pan Am, as a company that liaised not only with the US government but also with flying publics, maintaining a sleek, polished public image was crucial. Firms like MK, however, interacted almost exclusively with the United States and foreign governments; they spent almost nothing on advertising–and liked it that way. Hence, Van Vleck suggests, the earth-moving mode of mid-century American corporate globalism tended to reinforce American-supported dictatorships abroad, from South Vietnam to Indonesia to Chile. But civil engineerings' firms trust of hierarchical authoritarian government was more about power than politics: Kellogg (later part of Kellogg and Root) was the first American contractor to do business in Maoist China in the 1970s.

But Van Vleck hopes that Ambassadors With Bulldozers will help blend the history of technology with social and cultural history, too. Here, again, the differences between Trippe's corporate globalism and that of MK is telling. Both Pan Am and MK were patriarchal, male-dominated firms, but the ways in which they constructed American society and its gender norms abroad differed. Pan Am offered its mostly male travelers a sexed-up vision of the American woman in its flight attendants. Pan Am, along with other US airlines, famously imposed humiliating "size requirements" for its stewardesses, and throughout much of the industry, female flight attendants were forbidden to marry until the 1980s. (Some airlines even banned male flight attendants until the early 1970s.) Pan Am's ideal American woman was a perverse inverse of the American suburban housewife of the day–nubile, mobile, international, and willing to accompany the businessman abroad at all times while the wife provided security and tended to children in Levittown.

Civil engineering firms embodied different gender norms. While firms like MK had conservative white collar male cultures at the top, such firms necessarily had to employ armies of lower-class men to lug dirt, lay pipe, and drive the bulldozers. The man as corporate tycoon and Joe Six Pack existed side by side. But whereas the women of Pan Am were often aggressively sexualized singles, firms like MK created a new American female subjectivity–the company wife. Here Van Vleck is spoiled for sources, since Ann Daly (the wife of MK founder Harry Morrison) accompanied him around the world and wrote extensively about their travels. By including the voice of Daly and other company wives in the story, Van Vleck hopes to show how American empire was not only built literally with material culture abroad, but also through the reinforcement of new subjectivities at home.

•

As an assistant professor at an institution with a strong teaching emphasis, however, Van Vleck faces the challenge of not just writing but also teaching global history to students. That task has its own struggles. Students taking courses in the history of technology frequently arrive in seminars wanting to write the history of Twitter, the iPhone, or SnapChat, seemingly thinking that technology simply means "new."

Teaching Yale students to think more abstractly about the history of technology comes easily for Van Vleck, however, thanks to her status as a seasoned veteran of the early 2000s tech boom and all the utopianism it embodied. The siloing of teaching specialities and the curriculum poses obstacles to a more global approach, too: in addition to courses in the history of technology, Van Vleck teaches a course on "The Origins of US Global Power," but without more growth in scholarly literature or hiring for non-US international and global history positions it's challenging to offer a more synthetic global history course. This is less of a problem at more advanced levels of study at Yale, where Van Vleck, Adam Tooze (an upcoming guest to the Global History Forum), and Patrick O. Cohrs run an international history workshop for visitors.

Van Vleck's work belongs to a broader movement towards the internationalization of US history that scholars in other national fields would do well to learn from. When asked about works she admires or had been reading lately, Van Vleck named fellow Yale graduate Andrew Friedman's Covert Capital: Landscapes of Denial and the Making of U.S. Empire in the Suburbs of Northern Virginia, published in 2013 by University of California Press.

It's an appropriate choice, for what this reader finds in works like Friedman's and Van Vleck's is a rigorous awareness of scale and empire as internal and external process that global historians working on other regions might learn from. High-level diplomatic history is, and remains necessary as a scholarly field, but the work of these historians of the US in a global context suggests how this older style of "history from above" can be deeply conservative in an unintended sense, since it assumes that global history was shaped by–and primarily shaped–elite levels of statecraft. As Van Vleck's treatment of Pan Am and Friedman's study of CIA-world in Northern Virginia show, frequently we need to see international action through middle-tier actors–airline executives, individual secret agents, or the South Vietnamese–American diaspora to grasp the full implications of topics that have seemingly been studied to death, like World War II or Vietnam.

These works also suggest how empires configured not just the outside world but also internal space, too. Friedman's anonymous Northern Virginia suburbs formed the perfect location for South Vietnamese mass murders to reinvent themselves as Mr. Rodgers-lookalikes and owners of pizza parlors; Van Vleck's "ambassadors" bulldozed not only occupied foreign countries but also the tracts of corporate campuses in Dallas, Salt Lake City, Boise, and Phoenix–an alternative suburban corporate landscape in anchored not in Democratic New York, but in states that became part of an "emerging Republican majority" of the late 1970s. Historians of other empires–British, French, Japanese, Soviet–or even of smaller countries with regional or global ambitions–Yugoslavia, Germany, Korea–should read closely as they seek to add a global turn to the national histories they study.

•

Our conversation with Van Vleck turned out to be more long-haul than puddle jumper, but as the installment of Global History Forum shows, that's only because her work offers so much to engage with. It's hard to think of a better example of work that remains anchored in national history while richly incorporating a global point of view. It's been a pleasure to feature her as our latest guest to Global History Forum.