The Fiftieth Anniversary of India’s Peaceful Nuclear Explosion: An Interview with Jayita Sarkar

Today, May 18, 2024, marks the fiftieth anniversary of India’s peaceful nuclear explosion or PNE. To mark the occasion, the Toynbee Prize Foundation facilitated a conversation between historian Jayita Sarkar and myself. Dr. Sarkar explained what the PNE was and how it shaped Indian and nuclear history. In addition to the PNE, Dr. Sarkar and I also spoke about her acclaimed 2022 book, Ploughshares and Swords: India’s Nuclear Program in the Global Cold War which received the Bernard S. Cohn Book Prize from the Association for Asian Studies and Honorable Mention for Global Development Studies Book Award from the International Studies Association. The book can be freely read through its publisher, Cornell University Press, and here is a link to read my January 2023 Toynbee review of Ploughshares and Swords. Below is an edited version of our conversation.

Marc Reyes, University of Connecticut

MR: On May 18, 1974, India conducted what it called a “peaceful nuclear explosion” or PNE. For those unfamiliar with the term or the incident, what was it and its significance to Indian history and nuclear history?

JS: Fifty years ago, the Indian government led by Indira Gandhi conducted an underground nuclear explosion in Pokhran, Rajasthan, part of the Thar desert in the country’s northwestern region. It was a plutonium implosion device of the kind dropped on Nagasaki, Japan on August 9, 1945. Immediately after the explosion in Pokhran, the Gandhi government called it an experiment to explore the uses of underground nuclear explosions for civilian purposes, such as for mining and oil drilling.

The Pokhran explosion coincided with the Global South countries’ demands for greater economic equality in the form of a New International Economic Order or NIEO. The Indian government itself was a vocal advocate for NIEO, publicly invoking disparities between the developed and developing worlds as a significant issue on multilateral fora. The official ascription of peaceful uses made the Indian nuclear explosion a rhetorical device for economic decolonization against the backdrop of the 1973 oil shock and NIEO.

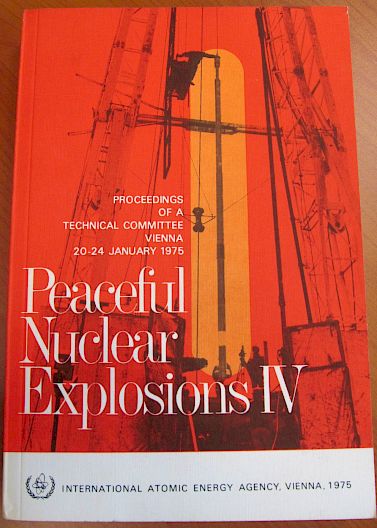

Nuclear explosion projects for civilian purposes had been underway in the United States and Soviet Union for decades prior, making “peaceful nuclear explosion” or PNE a familiar term within policy circles. Multilateral studies on PNEs had circulated at the Vienna-based International Atomic Energy Agency throughout the early 1970s. However, India was the first country that conducted its very first nuclear explosion underground and formally claimed that the explosion was to serve civilian purposes, thereby raising questions whether India had developed nuclear weapons instead. This was because technologically speaking, there was no distinction between a nuclear device used for creating harbors (as attempted in the United States) or lakes (as done by the Soviet Union) from that used as a bomb. Moreover, the nuclear explosions of the first five countries (United States, Soviet Union, United Kingdom, France, and China) that had conducted nuclear explosions before were aboveground, and none of them called theirs a PNE.

MR: After India tested its PNE, what were the domestic and international ramifications? Was it popular at home? Did other countries support or oppose it?

JS: The meaning-making of the 1974 Indian nuclear explosion was a Rorschach test: it was an inkblot that revealed more about the observers than what was being observed. It was a plutonium implosion device that was officially 12 kilotons in yield, measured 5.0 on the Richter scale, and made a crater 47 meters in radius and 10 meters in depth. Given its intrinsic ambiguity, the explosion meant different things to different audiences. Its significations were polyvalent. Naturally, the responses were multifaceted, both at home and abroad.

Nonproliferation hawks and India’s geopolitical adversaries saw the explosion unmistakably as a bomb. Modernization theory advocates considered it to be a prestige-driven demonstration by an impoverished country that had yet to take off: a paper tiger with no teeth and barely a meow. Actors who wanted to keep the option open to develop nuclear weapons by procuring technologies from multiple partners, saw a model to emulate. The ambiguity of the May 1974 nuclear explosion was not lost on domestic audiences. T.K. Mahadevan captured the explosion’s heterogenous implications, when he wrote in the Times of India: “The bomb, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. If you are a hawk, you will know it is a bomb. If you are a dove, you will pretend it is a device.”

Against the backdrop of an economic crisis exacerbated by the oil shock and social turmoil including railway strikes, the nebulousness of the nuclear explosion’s meaning allowed the Gandhi government to get away with it. The prime minister publicly reassured audiences at home and abroad that no additional expenses were incurred for the nuclear explosion. Legality was also a key dimension of the nuclear explosion. Nuclear explosions were only permitted underground under the 1964 Partial or Limited Test Ban Treaty, to which India was a signatory. I explore legality more fully in my book in relation to other treaties, export control mechanisms, and domestic transformations within India, especially the Emergency (1975-1977).

MR: In your book’s epilogue, “The Anti-Dissent Machine,” you write, “Freedom of action of the leaders of India’s nuclear program has transformed it into an anti-dissent machine” (p.203). Can further elaborate on how India’s nuclear program has altered, even stifled, dissent in India? Do you think national security projects, like nuclear weapons, fundamentally challenge or alter the democratic values of nations?

JS: National security projects can and do undermine democracy in the name of survival of the state, but so can development projects. The multifarious nature of India’s nuclear program meant that it served several interests of those at its helm: it was both a national security project as well as an endeavor for economic modernity. It was a vast infrastructure project that involved everything from mining and milling to reactors and reprocessing to space launch sites (the space and nuclear programs were closely aligned as I show in the book). In other words, the nuclear program was a manifestation of both the national security state as well as the developmental state.

When one reflects on what the implications were of this heterogeneous program in terms of accountability, one can see how it functioned as an anti-dissent machine. Opposing the nuclear program, was opposing modernity and survival, and thus was opposing the nation itself. One of the clearest instances were when in 2012 thousands of protestors at the Kudankulam nuclear power plant (in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu) were arrested and charged with sedition by the government, who called the demonstrators “enemies of the state.”

The anti-dissent machine of the nuclear program was the flipside of freedom of action. Different actors within the nuclear program had different priorities. Not only did freedom of action expand choices of those actors, but it also kept oversight at bay— at home and abroad— for the pursuit of different goals of the various actors. For instance, Vikram Sarabhai and Satish Dhawan, who led India’s space program at different moments, prioritized protecting the space program from outside interference and thus kept the space program at arm’s length from the nuclear program and defense laboratories. The Indian Planning Commission’s attempted oversight of the Department of Atomic Energy’s budget and projects encouraged Sarabhai and technocrats like M.A. Vellodi to maintain a host of projects that concurrently served civilian and military aims. So, the program’s polyvalence in practice undermined oversight and accountability.

MR: I am always curious about what was left on the cutting room floor. How did your book differ from your dissertation? Was there material from the dissertation that did not make it into the book? As one project became another, what didn’t make the final draft? What’s a document or source that you found during your research but just haven’t been able to use yet or find a home for?

JS: This is such a fun question to answer. I was over the word count for my book manuscript by nearly 12,000 words. So, almost a chapter's worth of prose did not enter the final version of the book manuscript prior to copyediting. Since the book’s publication, some readers have politely complained to me that the last chapter, “Explosion and Fallout,” felt a bit rushed and that I could have added more texture to it. I do not disagree with them, but the backstory was going over the wordcount.

In terms of the book-to-the-dissertation process, I conducted fresh archival research in several countries, found new digitized collections to use, had some wonderful colleagues share their own primary source materials with me, spent months thinking about the structure of the book, its overarching arguments and contributions, and shared drafts for comments from colleagues and friends who inhabited different historiographical worlds, from political and diplomatic history to history of science and technology to histories of decolonization. In other words, there was a lot of deep reflection and reformulation over several years that made the book what it became.

I did not wish to rush the book. So, right after the PhD, I began working on my second book project while letting ideas percolate about redrafting Ploughshares and Swords. Fortunately, I had the privilege of time and resources through a string of postdoctoral fellowships, research grants, and a tenure-track position to be able to do so.

As I had to leave sections out of the book, I was sad that primary source materials about the nuclear black-market from the Swiss Federal Archives could not enter the book. Several of those were police reports providing “thick descriptions” of smugglers and smuggling networks operating along the Swiss borders with France and West Germany: the European leg of what would become known as the infamous A.Q. Khan network of global nuclear smuggling from the 1980s to 2000s. Some of those materials were intriguing, showing palpably the fluidity of borderlands in Western Europe and the connections between territoriality and technopolitics, which as you know, are the two through-threads of my book.

MR: From my count, you conducted research at twenty-two archives in eight countries. For your study of India’s nuclear program, did you have a favorite archive?

JS: For the book, I conducted archival research from 2010 until 2018 while also delving into several rich digitized collections during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Each archive came with its own set of opportunities and challenges, some more impervious than others. Archives in India and France probably had the same level of bureaucracy, opacity, and uncertainty when it came to access. The smoothest experiences were unsurprisingly in the United Kingdom, Canada, Switzerland, and US presidential libraries. My favorites are where archivists tirelessly work in dusty spaces, cataloging materials, promptly answering researchers’ questions, making materials available, and going over the rules of the research room with big smiles on their faces. Without archivists, there would be no history.

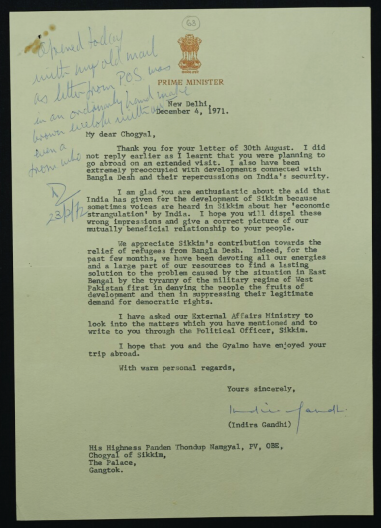

Letter from Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to the Chogyal of Sikkim, December 4, 1971, SPA/FA/IN/013, EAP880/1/2/24. (Cited and contextualized in Ploughshares and Swords: India’s Nuclear Program in the Global Cold War on page 179; footnote 74 of Chapter 7). This image is under a Creative Commons license: Link to full collection here (images attached): https://eap.bl.uk/collection/EAP880-1/search

MR: Can you please speak about the challenges and opportunities of writing histories of nuclear weapons and foreign relations of postcolonial countries?

JS: The challenges and opportunities of writing this kind of history is an important point of discussion. Let me divide my comments into two: one is archives, and the other is exceptionalism.

Here, I think it is important to first reflect briefly on the state of the field of the twentieth-century history of South Asia. Over the past two decades, owing to declassification of national, international, local, and private archives concerning the period after the formal decolonization of South Asia (1947–48), subject matters that were once the turf of journalists, retired technocrats, and policymakers witnessed fresh evaluations by historians. Heeding Tony Smith’s admonition to avoid “orthodoxy plus archives,” this new generation of trained historians has been pouring new wine in new bottles.

This new historical scholarship does not take ideological bromides such as the ‘Cold War did not happen in India because the country was nonaligned,’ or that ‘nonproliferation was a US concern that did not affect India’ at face value, thus bringing a much-needed corrective to our understanding of India and the role of Indians in the global twentieth century. When reading this new body of scholarship to which Ploughshares and Swords belongs, it is important for readers to be aware of this historiographical development and its intellectual effects.

Furthermore, over the last two decades, multi-archival and multilingual research has become the norm for those writing transnational and international histories, while political scientists adopting qualitative research methods have also joined in. The availability of primary sources in multiple countries has meant that it is sometimes possible to follow individual actors across multiple institutional spaces in different countries. As a result, researchers have to recognize their actors’ diverse performativity: what these actors said and did at home (say, peace-loving, Gandhian, reticent Sarabhai) and what they did abroad (ponder on placing nuclear devices along the Himalayas to deter China at a key meeting with delegates from the American Academy of Arts and Sciences) were often strikingly different— and the resultant meaning-making of all of this.

The other aspect is the exceptionalism of all things nuclear. All things fission-related are presumably so exceptional that they deserve, rightfully or not, their own histories: the so-called “nuclear histories.” This has led to the neglect of other important things that are connected to the nuclear story but treated as irrelevant. Moreover, there is overspecialization in our subfields of history and cognate disciplines. The “nuclear world” not only has its own jargon and acronyms, but is also inhabited by experts who are physicists, chemists, engineers, technology reporters, and social scientists, who have contributed their life’s work to the atom.

De-exceptionalizing the nuclear by foregrounding the social, political, and economic lives of the atom foments discontent amongst such experts, and perhaps even horror: Why talk about X when it is really about nukes? For me, challenging the exceptional nature of this history was an important intellectual goal. I did this through the territorial story— the spatial expansion of the postcolonial nation-state and the reformulation of its borders— concurrently with the techopolitics of ‘freedom of action’ in the nuclear and space programs. It is an intellectual endeavor I am continuing to pursue with my next book that foregrounds land, labor, and debt in the so-called nuclear story.

For me, challenging the exceptional nature of this history was an important intellectual goal - Dr. Jayita Sarkar

MR: Even after all this time studying India’s nuclear program, were there moments or information that surprised you? Was there a source or finding that surprised you the most?

JS: Quite a few things surprised me while writing the book. Let us call them the three Cs: companies, contingencies, and continuities. First, the long lives and reaches of companies made it possible to write an interconnected story of capital, commodities, and expertise in ways I had not initially anticipated. I was surprised to find that immediately after the division of Germany, Homi Bhabha and S.S. Bhatnagar visited East Berlin in November 1948 to meet the technical personnel of Auergesellschaft, the company in charge of developing the Nazi nuclear bomb, to find out what know-how could still be procured about nuclear fission from them. Similarly, the significant role of the Tatas and their global financial networks in the Indian nuclear program allowed Bhabha quite a lot of leeway and made the nuclear program a business-government joint endeavor from the very beginning. There are a lot of companies – US, French, Canadian, and others – that emerged as key actors in my book. If one reads closely, a reader can find a blueprint in Ploughshares and Swords for rewriting the history of India’s nuclear program through the history of capitalism.

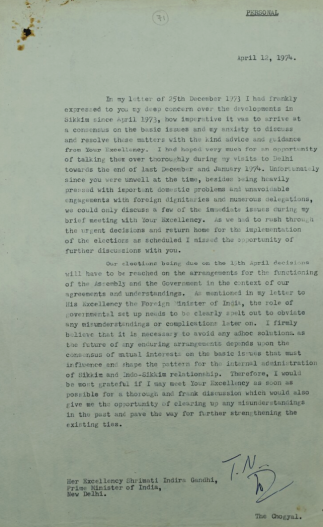

Second, contingencies are a key part of this story. It comes across most clearly during preparations of the nuclear test site in Pokhran, when one obstruction or another delays original plans. These matched closely with India’s slow annexation of the small mountainous kingdom of Sikkim, which surprised me. The connections between the two were very surprising to me, which I established using the Sikkim Palace Archives from the British Library. That said, I think we need further primary source research connecting the two. I have introduced the germ of an idea to the world with the hope that smart graduate students somewhere out in the world will make us smarter about this subject in a decade or less. I think it is important to encourage future scholars to think systematically about past events when records are fragmented, scant, and overclassified.

Third, I found more continuity than change than I had anticipated. Whether it was freedom of action/anti-dissent machine through opposition to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, playing multiple partners against each other to get the better deal, embracing legality, prioritizing reputation costs, and suppressing dissent, India’s nuclear program shows remarkable tendencies of continuity.

Personal Letter from the Chogyal of Sikkim to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, April 12, 1974, SPA/FA/IN/013, EAP880/1/2/24. (Contextualized in Ploughshares and Swords: India’s Nuclear Program in the Global Cold War on pages 181-2). This image is under a Creative Commons license: Link to full collection here (images attached): https://eap.bl.uk/collection/EAP880-1/search

MR: What do you have planned next? What books or projects are you working on that admirers of your work can look forward to?

JS: I am currently completing my second book, Atomic Capitalism. A Global History, which is under contract with Princeton University Press for their America in the World series. The book is a 100-year history of nuclear sites, from mining to energy to weapons testing, retold through histories of capitalism, empire, and decolonization. Research for this book has taken me to places I have never visited before such as the Four Corners of the United States and Namibia. It has been an exciting intellectual journey delving into new historiographical worlds for this book. I am on research leave next academic year to complete its writing. So, this would be the next thing readers would expect from me.

At the same time, I am continuing to think, research, and write for the next book project, Connected Partitions: A Global History of Territoriality, which is about the circulation of the idea and practice of territorial divisions from the South Asian subcontinent to the world. It is a fun project because it is very different from Atomic Capitalism, but just as fulfilling to me. The two are keeping me on my toes!

The only publicly available image of the 1974 Indian nuclear explosion. Source: Associated Press, published with permission in chapter 7 of Ploughshares and Swords: India’s Nuclear Program in the Global Cold War.

MR: Lastly, what did you think of Oppenheimer? Both as a moviegoer and historian of nuclear history.

JS: Ah, the eternal tension between being a scholar and a human. I watched the Oppenheimer in Edinburgh, Scotland where I live, on a weekday night in a near-empty theater. So, I was really able to focus! As a moviegoer for a movie that long, I was not bored at all. Time flew! The movie certainly has positive attributes in terms of getting young people interested in 20th century history and nuclear things in general. Several of my students at the University of Glasgow had discovered the Manhattan Project through the movie, deciding to take my Masters-level course, “Nuclear Technologies in History, Politics, and Society” last fall.

Many years ago, I had read the book, American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer, by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin for which they received the Pulitzer Prize in 2006, and on which the movie is based. I knew Marty Sherwin through various historians’ networks of the Wilson Center, and we were all shocked to lose him in 2021. I think the movie, which was exceedingly well done, certainly lived up to the expectations in terms of Marty’s legacy as a historian and a writer.

Now, as a historian dabbling in nuclear things for nearly 15 years, of course I could not help but notice the erasures. There are several. Oppenheimer holding a booklet on uninhabited land before choosing Los Alamos as the site renders Indigenous dispossession completely invisible. Where are the French, one of the leaders in radioactivity and nuclear fission research before the fall of Paris, who contributed to the Manhattan Project from Montréal? Having spent some time in the Belgian State Archives in Brussels and seeing how significant uranium from Shinkolobwe (or Mine S as in the documents) from the Congo was for Los Alamos, I could not help but notice the silence on the transimperial connections. Finally, it is very easy to watch Oppenheimer and imagine it was an all-American story. The Manhattan Project was at least a trilateral endeavor with the US, UK, and Canadian governments directly involved. Moreover, without immigrant scientists fleeing Nazi persecution from continental Europe, it would not have materialized. Fortunately, my students know that because I make sure they do.

Jayita Sarkar is Associate Professor of Global History of Inequalities at the University of Glasgow's School of Social and Political Sciences. Her research and teaching areas are global and transnational histories of decolonization, capitalism, nuclear infrastructures, South Asia, and the United States. She is a 2024-25 British Academy Global Innovation Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, D.C. Before joining Glasgow, she was a tenure-track Assistant Professor at Boston University’s Pardee School of Global Studies.

Marc Reyes is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at the University of Connecticut. He is completing his dissertation, “In the Circle of Great Powers: India and the Postcolonial Atomic State, 1947-1974.” His research and teaching interests include modern India, Cold War international relations, and the history of technology with a focus on digital media and online cultures. A Fulbright-Nehru alum, Marc is an Editor-at-Large for the Toynbee Prize Foundation. He also is a cofounder of Contingent Magazine.