Of Prostitution and Port Cities: A Conversation with Liat Kozma

Prostitution may be considered the world's oldest profession, but its practice and regulation has been far from fixed throughout history. As Dr. Liat Kozma explores in her most recent book, Global Women, Colonial Ports: Prostitution in the Interwar Middle East (2017), state-regulated prostitution in the Middle East—and the lives of prostitutes themselves—was directly influenced by major global shifts following World War I. These shifts included the transition from Ottoman to French and British colonial rule in the Middle East, as well as the ongoing processes of industrialization, urbanization, and large-scale migration set in motion in the nineteenth century.

Exploring prostitution through the regional lens of the Mediterranean—rather than through a political lens like that of a single nation or empire—Kozma innovatively dissects the many layers of state-regulated prostitution and the involvement of global and local institutions. From Casablanca to Beirut, Alexandria to Haifa, people, practices, germs, and attitudes toward prostitution and sexual practices migrated and spread during the interwar period.

Importantly, this story of the internationalization of prostitution regulation is far from one of top-down colonial policy-making. It involved a complex web of interactions and knowledge-sharing between individuals at every level, including actors from the newly created League of Nations, who sought to monitor traffic in women and children; colonial officials who shared policies maintaining racial boundaries between populations; local feminists, abolitionists, and medical doctors who wrote and debated about how to best prevent the spread of venereal disease; and individual prostitutes and brothel keepers who migrated to different cities in search of employment opportunities. As Kozma puts it, "the drunken sailor affected international policies on clinics that treated venereal disease, and international conventions affected the availability of care in his port of call."

Kozma's narrative telescopes in and out, between the local and the global; between the individual brothel keeper in Port Said and the League of Nations meetings in Geneva; between the syphilitic soldier and the history of Salvarsan. In doing so, Kozma sketches out a new model for writing global history—one that connects the dots between social history, women's and feminist history, and Middle Eastern history.

We recently had the opportunity to speak with Kozma, a senior lecturer in the Department of Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. We talked about her research process for the book and her main findings about prostitution in the interwar period. We also discussed some of the broader challenges of writing a social and gendered history of a global phenomenon, the exciting potential of multi-archival research, and her recent work in bridging the divide between academic and non-academic audiences through social history.

–Caroline Kahlenberg

INTERVIEWER

To get us started, could you tell us a bit about how you came to study history?

LIAT KOZMA

Well, I started out studying Middle East Studies and psychology for my B.A. at Tel Aviv University. I wanted to do psychological research because I was particularly interested in gender differences, and I thought that psychology would somehow give me answers. I was actually very disappointed with the discipline, and how it was taught there. History—and particularly Middle East history—seemed to be able to answer the kinds of questions I had, and in a much more nuanced way. I could do research papers and ask historical questions and get answers I was happy with, which were not quantifiable, as they were in psychology. So that's how I ended up doing history rather than psychology.

INTERVIEWER

And did you always think you would work on Middle Eastern history in particular?

KOZMA

I think the choice was political, but also practical. Again, I wanted to study psychology, and I learned Arabic in high school, so I thought that would be my second major. But then as it turned out, it became political for me in the Israeli context, studying the Middle East, Arab history, women's history. All of it was related to my personal politics, and how they evolved, especially during my M.A. studies at Tel Aviv University, but also during my Ph.D. years at New York University.

INTERVIEWER

Turning to your most recent project, Global Women, Colonial Ports, I'm curious about how the research and writing process differed from your other works. You've previously written about prostitution in the Middle East on a local and national level, particularly in Egypt. What led you to write this book as a global history of prostitution?

KOZMA

Yes, in my first book Policing Egyptian Women I looked at marginalized women in nineteenth-century Egypt, and what I ended up finding, even just looking at my secondary sources, was that similar processes were happening elsewhere, with regard to many of the questions that I'm interested in. So the question I became interested in here was what's specific to the Middle East, what's specific to Egypt, and what's specific to colonial situations? That was my conceptual starting point. And then in terms of sources, I discovered the League of Nations Archive in Geneva. What they offer you is a bird's eye view of the world, because the League of Nations investigators were interested in comparing the situation of prostitution and traffic in women in many different places, in tens of cities around the world. I thought that looking at prostitution globally could be an interesting project. And the fact that the League of Nations Archives gave me information about so many cities at once offered new kinds of questions, which I was very excited about.

INTERVIEWER

You've written in the past, in a chapter on "The Silence of the Pregnant Bride," about the tendency of historians to silence certain voices due to the lack of available sources and the way they choose to read them. Were you faced with such challenges in your use of sources for this project?

KOZMA

Yes, I used what was available to me. Historians of other places, of other societies, sometimes have diaries and memoirs, but we historians of the Middle East don't have much of that, until at least the mid-twentieth century. So the kind of sources I could access were mainly colonial sources and sources written by people who wanted to protect or control these women, or discipline them and contain their international mobility. These are the available sources. I started with the League of Nations Archives, and then I went to Nantes and London for the colonial archives. I also visited medical libraries and feminist libraries in London and Paris, and also the Egyptian national library and the book market in Cairo.

INTERVIEWER

You begin the book at the macro level, by outlining the creation of the League of Nations' Advisory Committee on Traffic in Women in Children (CTW) and its crucial role in producing knowledge and policy on global prostitution. How did this committee begin, who were its members, and what did they find in their travels?

KOZMA

The committee grew out of one of the articles in the League of Nations Covenant, which actually brought together several pre-war efforts to collaborate on an international level, including in international health, trafficking drugs, arms, and persons—that is, slavery. What the League of Nations was trying to do was think of a mechanism that would form, for the first time, coordinated efforts in a continuous manner. This is similar to the conventions that were signed in the first decade of the twentieth century, in which state representatives would meet and sign an agreement, but with those there was no follow-up mechanism.

The CTW compiled annual reports, which continued from the early 1920s until the end of World War II. Basically, every country reported on what they did that year in order to contain traffic in women and children, in the form of laws and other results. For example, they might have said "we expelled six Syrian women, we traced one Polish trafficker and expelled him"—this kind of information. But very early on, in 1923, the American representative (among others) realized that these reports discussed what the states wanted to present, but were a very poor or incomplete representation of what was actually happening.

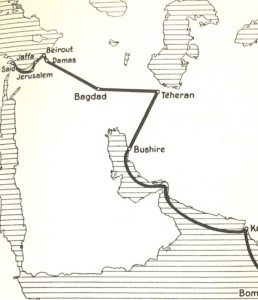

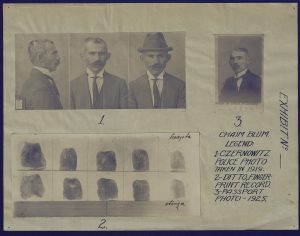

In 1924, the CTW sent its first traveling committee, comprised of three men who visited a total of 112 cities worldwide, mainly port cities, in Latin America, North America, and around the Mediterranean. The man who visited the Middle Eastern and North African ports was Paul Kinsie, an American investigator. In his role, he would pose as a pimp, and ask pimps around the Mediterranean how to smuggle in a seventeen-year-old girl. And they would tell him basically that it wasn't worth his effort, it's illegal, and that he should go for an adult woman, and these are the ways to do it. This is the kind of information I worked on a lot, mainly in trying to map the mobility of women around the Mediterranean. I used colonial archives to substantiate his conclusions.

It's also important to mention that the United Nations press just published the drafts of Kinsie's travels. In the volume, edited by Jean-Michel Chaumont and Magaly Rodriguez, there's a short introduction by a historian for each city; I wrote the introduction for Port Said, Nefertiti Takla wrote the introduction for Alexandria, Francesca Biancani wrote the one for Cairo, Camila Pastor wrote the one on Beirut, and Debbie Bernstein wrote the ones for Jaffa and Haifa. These notes are really a gold mine for historians, which are now available for all. I actually used them for teaching and it's fun, since students get a sense of the historian's raw material.

The report that was published in 1927 included a very selective summary of Kinsie's notes, with very selective conclusions. He ends up finding out that there's no such thing as an organized network or gang that controls traffic in women, and many of the women who are supposedly trafficked are some sort of labor immigrants. There is actually very little evidence of coercion, but plenty of evidence of migration. I can't say that I know why these women ended up in prostitution, but as far as migration goes, they tell him that they migrated willingly. And in certain places the women see him—an American with money, as he presents himself—as an opportunity for them to go elsewhere. That is, he meets with prostitutes and they ask him whether he can take them with him to America or elsewhere. The League's official conclusion, however, is that traffic in women is a widespread phenomenon, which sparks a lot of legislation in many places but also League of Nations recommendations and later conventions.

As I said, the annual reports continue until the 1940s. In 1932-3 there's another traveling committee, but this time the states don't want them to do undercover investigations, and they have to coordinate with the hosting state, which makes their conclusions very in line with how the state wants to present themselves. And this time they visit Asia—it's called the Traveling Committee to the East—and with the exception of Lebanon and Palestine, there is no overlap between the two reports. This report is more conventional; it's more about what the states are doing to control the trade, how successful they are, what voluntary organizations are doing. It's less about talking with the prostitutes and pimps and finding out what's going on. So this report is much less interesting for me as a social historian.

And then after this, in the late 1930s, what they do is more social work and sociological research, which I focus on less, looking at why women end up in prostitution, how they can be rehabilitated, and how different policies affect prostitution worldwide. There is more comprehensive research on the birth of this social work attitude toward prostitution done by my colleague Magaly Rodriguez Garcia.

INTERVIEWER

In addition to looking at the League of Nations, you focus on the role of the French and British colonial governments in controlling mobility, urban spaces, and prostitution during this time period. How was regulation of prostitution both an "inter" and "intra" colonial policy? And how did colonial regulation differ depending on location?

KOZMA

First, there's a basic early twentieth-century model implemented in different forms in Europe and in the colonies. The model assumes that prostitution is inevitable, and in order to contain its damages to public health, we must impose regulation. Regulation includes weekly medical examinations, and physically confining prostitutes to specific houses or neighborhoods so that they're not disturbing the peace of "respectable" parts of the city. The main difference in the Middle Eastern context is between the British and the French empires. Britain abolished legal prostitution at home, and the French did not. Prostitution was still regulated within France until 1946. But what they did in the colonies was different. The French mostly imposed regulation everywhere, whereas in the British colonies this wasn't always the case. For example, there was a very sophisticated regulatory system in Egypt, and there was some form of regulation in Iraq, while regulation was abolished in Palestine in the early 1920s, after a short-lived regulatory experiment.

This is one of the main differences in the Middle East and North Africa between the French and British policies. But then even within the French Empire, for example, there are differences. For example, in Casablanca you have Bousbir, the prostitution quarter, which was a walled-off quarter built specifically for this purpose, with identical houses, identical courtyards, identical rooms—really a Foucauldian kind of utopia.

But then when you try to export this model elsewhere, it doesn't work. This is because Casablanca was mainly a city built by French colonialism. In 1912, it was a small town, which was built up into a big city by the 1920s and 1930s, which allowed for new neighborhoods and new structures. Paul Rabinow is one important voice studying this urban design of Casablanca. But then when this model gets exported to Tunis or Beirut, for example, it doesn't work well, because there's already a vibrant city in place. When the colonial governments try to isolate prostitution to specific streets or neighborhoods, it doesn't work as well as they want to it. The neighborhoods are far more permeable, with people coming in and out, which is not what the officials want.

We know that these officials have Bousbir in mind, though. For example, during World War II the French high commissioner in Beirut writes to his counterpart in Morocco and asks for a model and for personnel. He asks for recommendations on how to build a red-light district like Bousbir in Beirut, and whether they could recommend some people to come from Casablanca to Beirut to build such a quarter. It's not implemented, but there's an attempt.

Several years earlier in 1935, similarly, the French officials of the Tunis municipality visit Algiers and Casablanca to study regulation regimes in these cities in order to implement something similar in Tunis. What they want to do is to destroy some parts of Tunis to build a red-light district at its center, because they think the main mistake made in Casablanca was that the quarter was built a few kilometers out of the city. There is an objection to this by the residents of Tunis, and the plan wasn't implemented.

INTERVIEWER

And are the British and French colonial governments in coordination and communicating with one another, as well?

KOZMA

I know they're at least looking at one another. For example, when there's objection in Beirut to the regulation of prostitution, French officials are saying, "look at Haifa, an abolitionist city, and look how messy it is there. We don't want Beirut to be like Haifa." Or another example—in 1919 when the British forces in Port Said encounter the French forces, the French say about the British that abolition is reducing promiscuity among soldiers, and that maybe the French should adopt it too. The French forces are coming to Port Said and they find the city to be abolitionist in the war years and they are sort of jealous. These are the kinds of encounters that I found between the British and the French.

INTERVIEWER

And now to turn to the prostitutes themselves. What did you learn about them—who were they, where did they come from, and what might they have experienced? Of course, you've mentioned that it's difficult to know the exact reasons for their migration, especially since you don't have their voices directly from your sources, but what were you able to find out about the women?

KOZMA

First, we know very little about local prostitution from the kinds of documents I looked at. Scholars working in other kinds of archives can learn a lot more. I'm thinking here of Hanan Hammad in her book Industrial Sexuality: Gender, Urbanization, and Social Transformation in Egypt (2016), who looks at archival records in Egypt and finds so many interesting things on local prostitution. What I mainly learned, because the League of Nations was interested in traffic in women internationally, was mainly about foreign prostitution.

In the book I talk about three categories of women: first, East European Jews, who were disproportionately represented in the Middle East as well (I'm saying "as well" because a lot has been written on the role of Jewish procurers and prostitutes in the Argentina story). Some of these East European Jews reached the Middle East, mainly Egypt and Palestine and North Africa. They're interesting because the story of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century is mainly about families who migrate for a better future to the Americas or elsewhere. Here, we find the story of those who were marginalized, and who were already marginalized at home. Some of them were marginalized through the immigration process. For example, some Jewish reformers at the time were talking about how Jewish marriage laws was causing prostitution among these kinds of women, because men would migrate first (often to the Americas), and plan to send home money and bring their families with them, but years went by and it wouldn't happen. Some of these men died, were killed, or ended up forming new families and new lives in the Americas or wherever they were, and the women were left behind but could not be released from the bond of their marriage due to Jewish religious law. There was a lot of talk in Jewish sources at the time about the relationship between these rules of Jewish marriage, which don't allow women to be released from a marriage if the man doesn't explicitly divorce them, and how it could lead to prostitution.

The second group I discuss is Southern European women—Italian, Greek, French, Spanish, Maltese. We can find them in our sources in colonial North Africa, from Egypt to Morocco. Again, these women are part of a larger wave of migration, like the Jewish women are part of a wave of Jewish migration outside of Eastern Europe. There are about two million Europeans who end up settling in North Africa in the colonial years. What they can gain is legal privilege. That's why I call them immigrants and not traffic victims. Many of them, at least according to the sources, already worked as prostitutes in Southern Europe, and then had the opportunity to move to North Africa where they were above the law in certain situations, mainly in Egypt, due to the Capitulations. [The Capitulations, which were enforced in Egypt until 1937, allowed citizens of certain European countries to be legally persecuted only by their respective consulate, placing them above Egyptian law in many cases. In turn, this made it difficult for Egyptian law enforcement authorities to impose existing legislation on nonregistered prostitution and brothels.]

The third group, which I know less about, is internal immigrants. I'm talking mostly about Syrians, who migrate to Iraq and Egypt. Again Syrians and Lebanese, from the late nineteenth century, are leaving Syria and Lebanon, so part of this wave of migration also includes these women.

INTERVIEWER

And what about the procurers and the brothel keepers? I was interested to learn that these were both men and women.

KOZMA

Yes, legally, brothel keepers could be only women, in regulated systems. These were mainly Europeans (again, there were also local ones, but I don't know much about them). The ones I know about were mainly European women who were former prostitutes who became brothel keepers in later years.The men were of all nationalities. The League of Nations investigator, Paul Kinsie, spoke French, Yiddish, and English. So he spoke mainly with the French and Jewish procurers, but I assume, just looking at the numbers, that there were others, who were the same nationalities as the women.

INTERVIEWER

You also discuss the prominent role of doctors in conceptualizing prostitution during this period. How did the medical findings and discourses help shape policies and norms about prostitution, and how was this period unique?

KOZMA

What is unique to the period we're looking at is the availability of Salvarsan and the Wassermann test, which were both discovered in the first decade of the twentieth century. This means that, beginning around 1909, you can diagnose syphilis and distinguish it from other diseases. Salvarsan is the first solution that can actually cure syphilis if diagnosed early and if injected regularly over the course of several months.

These two discoveries gave doctors a more powerful say in prostitution regulation. If regulation is more moralistic in the nineteenth century, in the twentieth century it's much more rationalized and related to the spread of venereal disease. This gives medical doctors much more of a voice than they had in the nineteenth century because the question of how can we cure and solve certain problems is much more acute during this period.

The question of eugenics was also very relevant to doctors. The question was not only how can we cure syphilis, but also how can we diagnose prostitution as a social evil and cure society from it by implementing eugenic principles. Eugenics in this discourse was seen as a progressive ideology—not terminating anybody, but making sure that the right people intermarry. And as I mentioned earlier, there was a rise of social work as a scientific project, which allowed doctors and social scientists to say with a lot of confidence that social problems could be solved, that they could eliminate certain kinds of social ills by programming society better.

So if we're asking what's unique to the twentieth-century discourse on prostitution and why doctors were such a prominent part of this discourse, it may be the optimism and belief that social sciences, and science in general, could revolutionize society and rid it of its social ills that plagued society since time immemorial. People really believed this in the 1920s and 1930s. You see the pathos with which doctors wrote about prostitution, and they believed that if they didn't have the answers, that with enough research and intellectual investment, eventually these problems would be solved on an international level. The League of Nations is important here; it's collapsing in the 1930s politically, but intellectually, they're still saying that they can bring the best minds to Geneva, and that whatever cannot be solved on a national level, with individual intellectuals and doctors scattered around the world, they can bring them together either through correspondence or actual meetings and find solutions to specific problems. And they are so optimistic, because in certain fields this is in fact happening. In the medical sciences, there were quantum leaps in what humanity knew about biology and medicine, and they were equally optimistic about the social sciences.

In this book, I take two case studies: Egyptian doctors and French colonial doctors in North Africa. I compare what they say about prostitution and venereal disease in North Africa, and the different positions they take on whether this can be solved and how.

INTERVIEWER

And what was the relationship between the doctors and the medical discourses, on the one hand, and abolitionists and social reformers, on the other? Were they in conversation with one another?

KOZMA

Feminists and abolitionists were certainly reading what doctors had to say about regulation, especially when they said that regulation was failing medically (which was true), and that it was impossible to contain venereal disease through regulation, since most women were not registered and not regulated. In practice, regulation was only imposed on about 10-20% of all prostitutes (the numbers varied), but the argument was that it was failing and that it wasn't practical. So abolitionists and feminists were reading this and using it to claim that regulated prostitution should be abolished and more humane practices should be adopted, like voluntary clinics, voluntary registration, and so on.

The other line of argument used by abolitionists and doctors was about the double standard, that women were the ones inspected and men were not. Medical doctors said it didn't make any sense to inspect only women, because both men and women were infected and were infecting others. Abolitionists then used this to say that if there were voluntary clinics, both men and women would go there, and there wouldn't be only women punished for a crime that had two parties.

Here, these groups had a lot in common. I see it mainly in abolitionists reading doctors, but I have no doubt that doctors were influenced and reading the abolitionists' articles or whatnot as well. They weren't explicitly citing abolitionists, but they were making similar arguments.

INTERVIEWER

You also mention how during this interwar period, the norms of what constituted healthy male sexuality changed. How did they change? And were female sexual norms changing too?

KOZMA

I'm building on Hanan Kholoussy's work on the marriage crisis that made modern Egypt. She looks at how the double sexual standard and the fact that men frequented prostitutes was questioned in early twentieth-century Egypt. People said, "we can't have our men marry when they've already had sexual experience with prostitutes." They argued that when the marital union begins with a virgin bride and a man who slept with prostitutes –and the husband approaches his wife like he did his former sexual partners – it creates a rift from the onset of marital life. Doctors and feminists were writing about this, criticizing what might have been a norm at least among certain classes of men.

I don't know whether less men did in fact frequent prostitutes, but the question of whether it was okay, whether it was a normal sexual behavior for unmarried men, was criticized in Egypt in the 1920s and 1930s. I'm thinking of Rose Haddad, who was an editor of a women's journal in the 1920s-30s, writing about prostitution. A man writes to her journal from Lebanon and says men have their sexual needs, that they can't wait until marriage, and that now the marriage age is rising, and they just can't wait. Haddad answers—and you were asking about female sexuality, which is hardly discussed during this period—that women also have their needs, and as much as they can wait until marriage, so can men.

Another kind of debate that I'm interested in is the debate within the British and French empires about the sexuality of sailors and soldiers, and what is okay for them to do after-hours in international ports. One attitude says, we know that they frequent prostitutes, so the least we can do is to make their sexual encounters as healthy as possible. There is a debate, for example, in the New Zealand army stationed in Egypt on whether to give soldiers on leave tubes of Salvarsan, and whether this would encourage promiscuity or just ensure that their soldiers would come home safe and healthy. This attitude admits that they go to prostitutes, and that they should be as healthy as possible, whereas another position is that the soldiers should be prevented from frequenting prostitutes by devising all sorts of distractions for them like sports and musical events.

INTERVIEWER

In terms of writing a global history, it seems that we often think of social history as using a micro lens, but in this project, you're using both a macro and a micro lens to trace global developments. What were the challenges of writing social history on a global scale?

KOZMA

I think this is a very critical question, and a question I was struggling with as I was writing—how is it a social history at all, if I'm looking at this global scale. What I try to do in terms of my writing strategy is to balance the two: to move back and forth between the macro and the micro, and show how the micro is constituted by the macro, and how the macro is actually the product of multiple micro examples. This is what I try to do, and that's what I think a good social history of globalization can show: that we can see the macro only if we look at specific examples around the Mediterranean that create those global processes. And that the global processes are not abstract but they're impacting concrete people's lives.

I must say that in comparison to my first book, my PhD research, here I had fewer voices of women. The voices of women were so heavily mediated by abolitionist agendas or medical representations that I couldn't say for sure where the woman's voice was and where it was the abolitionist speaking or a doctor trying to make a point. By relying on the micro examples that I did have, it was less of a social history than I would have liked, just because the sources do not allow the kind of nuanced social history that I love to do.

INTERVIEWER

Speaking about the voices of women, you've discussed in the past the need to mainstream Middle Eastern studies in gender history, and also to mainstream gender studies in Middle Eastern history. I'm wondering if you see your research as an attempt to mainstream gender in the field of global history? And more broadly, how might gender analysis be incorporated into global histories?

KOZMA

There are several other works being done now about the League of Nations from a gendered perspective, and about how it created forums for women internationally to talk about their rights and about colonialism. The League of Nations was also the first international organization that included gender equality and affirmative action in its hiring policies, so you see women not only as country representatives but also in the administration. I'm thinking about Susan Pedersen's work on women who had leadership roles in the League of Nations mechanisms and how it affected the League of Nation's agenda. Certainly, in the League of Nation' Advisory Committee on Traffic in Women and Children and the Children's Welfare Committee, women were represented in numbers that were unprecedented for international forums. So how the League of Nations created these opportunities and what kind of discourses this enabled is a story that historians are now telling. I think there's a lot more to be said about it.

I'm also thinking of the work of Sarai Aharoni, who looks at the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean from a gendered perspective. She focuses on the Sixth Fleet and the bars and informal brothels in Haifa, Israel. She shows the larger story about the Cold War and American global power, but she also zooms into the micro history of the bars these men frequented and a rape case that was adjudicated in Haifa in the 1980s. This story of American domination in the Middle East and how it impacted local communities is narrated through this gendered lens, and is really interesting.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any advice for scholars and students pursuing this type of global and gender history, on methodologies and how to read sources?

KOZMA

I think that multi-archival research is something that people are doing more and more now, and I find it to be very exciting. We can do it more now than in the past partly because of digitalization, and because digital cameras make archival visits shorter and more effective. We have the same limited research funds, so multi-archival research can also be facilitated by collaboration between researchers and students working on similar questions in different archives. I think writing global history by looking at various locations has a lot of potential. People are starting to do this, and the conclusions are very exciting. There's a lot of talk about the nationalist epistemology of historical studies, and I think not enough is being said about how it's related to the limitations of archival research—our archive is limiting our perspective. So if we collaborate on archival research, if we collaborate as scholars, we can do really exciting historical research.

My colleague that I mentioned, Magaly Rodriguez Garcia, and I thought a while back about writing a comparative work in which I would write about the Middle East and she would write about Latin America in relation to traffic in women and the League of Nations committee. In the end it didn't happen, but I think this kind of idea is something that can work. Historians of the Middle East working with historians of Latin America, North Africa, doing something truly regional or global—I think that's the future I see with this kind of research.

INTERVIEWER

Switching gears a bit, I'm wondering if you might speak briefly about the "Social History Workshop," a Hebrew-language blog that you co-founded and co-edit for Haaretz newspaper, which publishes short articles written by historians on a wide array of topics related to Middle Eastern history. [Some of the articles have been translated into English here.] Where did the idea for the blog come from, and why did you choose to focus on social history?

KOZMA

Well, we were inspired by the Ottoman History Podcast. But to back up a little, I did my B.A. and M.A. here in Israel at Tel Aviv University. My teachers there gave me the impression that there were two choices for an Israeli academic doing Middle Eastern history. One option was to talk and write in the press on whatever topic—for example, if you are a historian of nineteenth-century Egypt, you could certainly talk about Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood or whatever—this was one way of interacting with the media. The other way of interacting with the media was refusing to collaborate. This is what some of my teachers taught me, and this is the attitude I adopted as a graduate student: I'm a historian of nineteenth-century Egypt, and that is all I will talk about. So if somebody invites me to speak about something in the press, I have to refuse, unless they decide they really want to learn about the legal system of nineteenth-century Egypt.

Between these two attitudes, I chose the more isolating one—that we're not interested in effecting change in public opinion, and we can't. I grew up academically believing that there were just these two options. The thing is that in Israel, and I think it's the same for the American press, what you read about the Middle East is often very biased, and what you read here about history is very Israeli or European. So faced with these two dilemmas—one, either shying away from the press or talking to the press on whatever they want to hear, and two, the fact that the press is very biased about the Middle East and what history is—we (myself, On Barak and Avner Wishnitzer), started carving out this niche. We had been friends for a while, and we started thinking about what we could do differently. We brainstormed, and this idea came up. We prepared a list of where we want this blog to be hosted, and Haaretz came up. They gave us a two-month trial, and it never ended.

The rules for the blog are simple—1000 words about your research in language that is accessible to all, no jargon and no assumption of prior knowledge. We are three editors and a coordinator, Nimrod Ben-Zeev. We all do it voluntarily.

INTERVIEWER

Have you gotten much feedback on the blog?

KOZMA

Yes, we get feedback from two kinds of readers: general readers and academic colleagues. For our colleagues, this blog is a way to learn what other scholars in Israel are working on. We also know that people might not read the academic articles in the International Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, for example, but they might read a shorter article in Hebrew.

Another kind of feedback that authors sometimes tell us they receive is from people who contact them with personal stories, sometimes relevant to their research. Some of this feedback is very useful, which we wouldn't have gotten otherwise, because it's not the usual academic readership.

The main thing we've learned through the blog is how to translate our research to the public and make it interesting for a non-academic audience. This is the central thing we do as editors—we have to tell people, for example, that this is a term nobody outside academia knows, or that they can't squeeze in everything they know about something into 1000 words.

And we get feedback from authors that this dialogue in the editing process, which goes on for two to six drafts, helps them clarify their own argument, by forcing them to say things briefly and clearly to a non-academic audience. Sometimes we academics hide behind words instead of clarifying what we want to say.

INTERVIEWER

Yes, I imagine that's definitely a challenge for historians used to writing lengthy articles and books. Well, we've come to the end of our conversation, but I wanted to conclude by asking what else have you been working on since completing your book project?

KOZMA

I recently received a large grant from the European Research Council (ERC) to conduct research over five years on the regional history of medicine in the Middle East. This will mean having a team of postdoctoral fellows, doctoral, and M.A. students, and we'll be doing a part of what I mentioned earlier, multi-archival research. So people will be working on different regions in different archives and different languages, but under the same umbrella of the regional history of medicine in the modern Middle East. The questions I was interested in my book, like ideas that began in one place and moved to another, questions about how policies were implemented, experimented with, and exported, and about people who were trained in one place and worked in another–these are the kinds of things that our team will be working on. The challenge will be to make it one project, which is something that we don't do often in the humanities, but ERC grants enable us to create some sort of laboratory in which we're all working on the same question together. We'll meet on a weekly basis and talk about our difficulties and challenges. We'll start in September, though we already had our first introductory team meeting. It's an exciting project, and has a lot to do with team work. I have a lot of people to learn from and I'm in constant dialogue with women who received a similar grant in the faculty of humanities over the last few years. It'll be a lot of learning how to run a team, which is something we don't learn to do very often in the humanities.