Review—In a Sea of Empires: Networks and Crossings in the Revolutionary Caribbean

Mulich, Jeppe. 2020. In a Sea of Empires: Networks and Crossings in the Revolutionary Caribbean. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

Reviewed by Henry Jacob, University of Cambridge

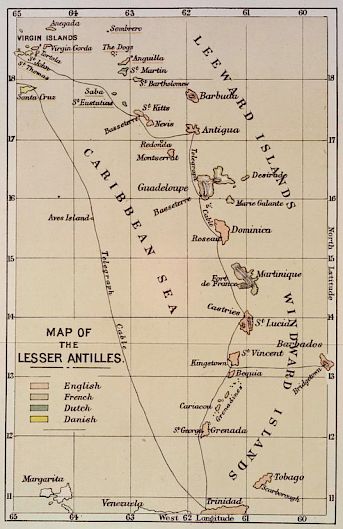

Jeppe Mulich’s In a Sea of Empires addresses how to bridge the local and the global, an issue central to global history since its birth as a subfield. The author rests his approach upon a bold claim: interimperial microregions are crucibles of early globalization. To prove how the microregion “provides an analytical ideal-type that is pertinent to a variety of historical contexts,” Mulich advances his thesis on two levels, one theoretical and the other historical. To start, he constructs a framework for interpreting microregions from a set of thematic categories ranging from the political to the geographical. Putting this concept into practice, Mulich focuses on the Leeward Islands, a Caribbean archipelago, from 1783 to 1834. In doing so, Mulich brilliantly demonstrates the Leeward Islands’ historical importance and provides a typology for microregions on a global scale.

To reveal how this interimperial system operates in the leeward Islands, Mulich structures his four core chapters around the topics of race, sovereignty, jurisdiction, and commerce. Rather than peripheral, the Leeward Islands proved to be a metaphorical and physical center of the tumultuous Age of Atlantic Revolutions. The British as well as the Danish Virgin Islands and St. Barthélemy, the primary subjects of Mulich’s examination, elicited a host of imperial ambitions and as a result changed hands often. For this reason, these colonies gained hybrid identities, filled with peoples holding increasingly tenuous ties to their homelands. The widespread practice of smuggling offers a telling example on the blurred distinction between one’s duty to country and desire for profit. In 1821, William Ingram, the customs officer on Tortola in the British Virgin Islands, came under the Crown’s scrutiny for secretly facilitating contraband while nominally upholding strict commerce laws. Rather than an isolated case, Ingram points to how it “proved notoriously difficult for imperial authorities in the smaller island colonies to fill customs offices with individuals who were trustworthy and effective in carrying out their duties.” Emphasizing further the fluidity of these mobile, polyglot zones, Mulich showcases the relationships among often overlooked empires such as Sweden and Denmark-Norway. Mulich stresses that these Scandinavian trading companies, though “shaped in the image of rival European companies” and thus filled with high hopes, neither empire gave much attention to the minutiae of governance on the ground. Because “day-to-day administration was parceled out to semi-autonomous third parties,” the Swedish and Danish holdings eventually spiraled to decline. Although Mulich also relies on British and French sources, he stresses the decidedly protean nature of this network through this emphasis on Scandinavian actors. In his own words, the Leeward Islands were “porous in regard to territorial control, but they also exhibited a pronounced sense of imperial transience.” The ephemerality of outside rule engendered slippery and often violent interpolity encounters across formal and informal channels.

The exchange of peoples and contraband set the chaotic rhythm for life in the Leeward Islands at the turn of the nineteenth century. For Mulich, these two trafficking practices became the “strongest drivers of this regional integration” partially because they crossed borders and boundaries. Chapters two and three describe how illicit trade and anxieties about slave revolts reinforced each other, blending tensions over security, profit, and opportunism. Notably, these currents of tense communication traveled along a common interimperial wind. As many of the Leeward Islands proved individually underequipped to repel a full-scale rebellion, governors such as the Swedish Carl Fredrik Bagge worried that a mélange of peoples inspired by slaves and in the wake of the French Revolution were “‘holding meetings and speeches on the rights of man, irrespective of his color.’” Interestingly, the “thin sovereignty” that Denmark and Sweden exercised over their possessions only exacerbated these cycles of real and perceived threats. To outline the consequences of this volatility, chapters four and five underscore the mutability of, and disjuncture between, affiliations of power and knowledge. For example, legal customs morphed and conflicted often, especially in laws over privateering and slavery, as they were translated across multiple tongues and reinterpreted in complex situations. This issue relating to prize courts became particularly acute in the 1790s. With courts on almost every individual island within the Leewards, a sailor could encounter temporary or permanent institutions run by British or French officials with either little or adequate training, often the former rather than the latter. Due to their propagation, these prize courts, especially British ones, gained increased autonomy from London – such freedom led to irregularities and the improper exercise of authority. In turn, it became natural for traders such as Philadelphian Jesse Pritchett to mask his identity in hopes of avoiding seizure. As Pritchett wrote in 1798, he had “‘become a Danish Burger and am Respected in that Capacity.’” As Mulich’s attention to characters such as Pritchett show, no single locus of government existed in the Leewards; because of this, the microregion almost like a prism, reflected a variety of meanings for its diverse inhabitants.

As a whole, Mulich’s treatment of the Leeward Islands complements his potent theoretical argument. In depicting the texture of everyday experiences in the Leeward Islands, Mulich successfully illuminates how this dense web of polities linked to early stages of globalization. To his credit, Mulich not only deftly weaves through a rich array of individuals’ lives and letters, but also ties them together in a wider interimperial narrative. The author’s attention to the commercial and migratory networks in the Caribbean bolsters his wider thesis on the two-way relationship between regional actors and global forces. With this in mind, Mulich’s contribution to the literature stands as a unique and notable one. Without doubt, In a Sea of Empires will interest scholars from a variety of subfields and disciplines concerned with the formation of maritime empires and the growth of globalization.

As excellent as this work may be, it still might leave readers with some questions. In the conclusion, Mulich gestures to other interimperial microregions of the nineteenth century and their relation to the Caribbean. In pointing toward sites such as the Gold Coast, Singapore, and Seychelles, Mulich invites readers to reconsider the viability of his “ideal type microregion” on a wider scale. Although the author takes care to identify the Leeward Islands as an embodiment, rather than the definition, of the microregion, one could nonetheless wonder where the line falls between theory and history, generalization and specificity. How close exactly are these “overlapping levels of interaction and authority” across microregions? Perhaps these worries are inevitable due to Mulich’s ambitious aims and the inescapable limits of a book’s page length. To be fair, only so much can be said in a couple hundred pages; the “networks and crossings” that Mulich probes here signal to the potential for overlapping studies in the future. Indeed, the fact that In a Sea of Empires provokes so many queries attests to its merit. In equal measure, answers to these questions can only emerge as more scholars follow Mulich’s lead and test this innovative global model in other local cases.