Roundtable—In the Land of Forgetfulness: History, Memory, and Culture in Disney’s Encanto

White Colombia! reads a bright flyer on the window of my local corner shop in Berlin, Germany. To sell a new energy drink for German consumers, this brand appeals to one of the most ingrained and widespread tropes about Colombia in the global cultural imagination: the country’s close connection to cocaine. Indeed, like many other Colombians, my experience of living abroad has been punctuated by recurrent but mostly harmless encounters with this trope. Not long ago, Netflix even deployed a massive poster in Madrid’s central square to promote its show Narcos, alluding to the motif of a “white Christmas”—an incident that led to a diplomatic row in which Colombia’s former president and foreign minister intervened. For many, this slice of Colombia’s troubled past determines the cultural representation of Colombian history for global audiences.

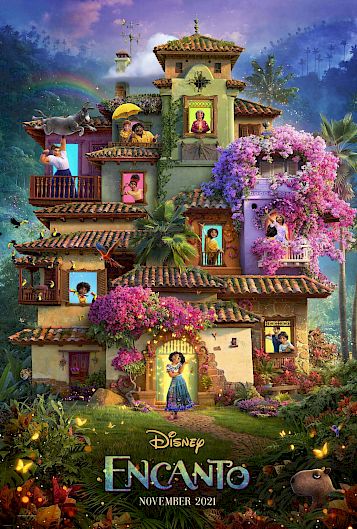

Last December, Disney also installed a banner in Madrid’s Plaza de Sol. In a wink to the Netflix-Narcos diplomatic scuffle, Disney instead promised its viewers a “colorful Christmas” with its new picture Encanto (2021). Praised for its efforts to give a chance “for a new generation to view Colombia in a fresh light,” the film revolves around a multi-generational household. Carefully crafted by a diverse team at Disney (and with the advice of an ad hoc group of native informers grouped around a ‘Colombian cultural trust’), this new movie has swayed audiences and reviewers across the globe. It was just awarded a Golden Globe prize in January 2022 (after receiving three nominations). In fact, its attention to detail and creative but consistent depiction of “Colombianity” has been widely celebrated. One could highlight its portrayal of racial diversity, its lack of traditional “villains,” or its strong female characters. Its songs, composed by Lin-Manuel Miranda (whose previous musical Hamilton already raised many questions about the public uses of history), have taken the charts by storm. Its score—created by Germaine Franco, a veteran of Disney’s previous Mexican-inspired Coco (2017)—has been recognized for its adaptation of local musical traditions. In sum, the film aspires to provide a new visual and acoustic vocabulary of what it means to be Colombian for moviegoers in this country, Latin America, and beyond.

And, as such, it offers a promising entry point into a more sustained scholarly inquiry into questions of representation, memory, and culture in global history. Of course, the movie does not aspire to offer a “truthful” representation of Colombia’s troubled history—in fact, its ambiguous chronology and geography show that the Encanto’s Colombia is as much imagined as it is real. But, at the same, how the film curates and packages certain elements of Colombia’s past for global audiences provides much food for thought. In its narrative, for instance, some saw a wider metaphor about the state of Unitedstatesean fragmentary politics; others saw a call for the reimagination of “romantic love,” a meditation on the “crushing weight of tradition,” or a commodified and whitewashed “Disneyfication” of Latin American cultures that caters to the growing market share of Hispanic-Unitedstateseans. In other words, Colombian history in Encanto serves as a mirror in which a global viewer can find herself, to paraphrase the legal scholar Paul Kahn. For example, I was particularly gripped by the subtle shadow that displacement casts over the whole narrative. Despite its toned down and relatively ambiguous portrayal of violence, the possibility of impending doom felt much more real than in previous children’s movies. Yet, does this feeling respond to the portrayal of Colombia’s 20th century civil strife or to our own age of uncertainties? I couldn’t say.

To tackle this and many other questions, we have convened a roundtable with three Colombian(ist) scholars. Our purpose is to interrogate Encanto’s politics of historical representation without either blindly celebrating or condemning its efforts. Instead, we “find ourselves” in this movie—questioning the ways in which it uses history for the enjoyment of an increasingly globalized public. We thank the three of them for their time and we hope readers might find these reflections relevant for their own attempts to see themselves in Encanto. Without further ado, let’s talk about Bruno.

—Daniel R. Quiroga-Villamarín, Graduate Institute Geneva.

Participant Bios

Robert Karl is a Professor of Arts & Humanities at Minerva University. He is a historian of modern Latin America and the Caribbean. His research examines the social history of politics and ideas, with a focus on the intersection of peace, conflict, and society. He is the author of Forgotten Peace: Reform, Violence, and the Making of Contemporary Colombia (2017) and is the host of the Research/Craft YouTube series.

Mariana Díaz-Chalela is a History PhD student at Yale University interested in Latin American twentieth century history, with a special interest in Cold War politics. She is also interested in legal history, the history of religious movements, and constitutional history. Before her doctoral studies, Mariana was a lawyer in Colombia. She graduated from the Universidad de los Andes, where she also did a M.A. in history.

Jorge González-Jácome is an Associate Professor and the Director of the PhD in Law programme at the Universidad de los Andes’s School of Law. His work revolves around human rights, the theory and history of law, law & literature, and constitutional law. He is the author of Estados de Excepción y Democracia Liberal en América del Sur: Argentina, Chile y Colombia 1930-1990 (2015), Revolución, Democracia y Paz: Trayectorias de los Derechos Humanos en Colombia 1973-1985 (2019), among other edited volumes. He also co-hosts the podcast El Derecho por fuera del Derecho on law, literature, and the humanities.

Roundtable Discussion

Robert Karl, Minerva University

As a scholar of Colombia’s armed conflict, the centrality of forced displacement in Encanto most jumped out at me. Of the more than 9.2 million Colombians who have been formally accredited as victims of the current armed conflict, the largest portion—8.2 million—are victims of forced displacement. In other words, one out of every six Colombians has been affected by forced displacement since 1985. A similar percentage of Colombians may also have experienced displacement during the so-called Violencia, the period of state terror and partisan conflict that occurred from the mid-1940s to the late 1950s. Encanto thus presents audiences with one of the central problems in recent Colombian history. Not your standard children’s movie fare.

Encanto’s treatment of this issue cannot help but be partial, so let’s take it as an invitation to consider the relationship between the past, present, and future of violence and forgiveness in Colombia. Much as Encanto presents us with a geographically and culturally unspecific mashup of Colombia, the story is located in a sort of timeless past. The film could just as easily take place during the War of a Thousand Days at the start of the 20th century as during the midcentury Violencia. In this, Encanto avoids the compression and scrambling of chronologies (and of course the sensationalist depictions of drug violence) of Narcos or even The Two Escobars. Nonetheless, at the same time, Encanto tends to reinforce a problematic portrayal of violence as a timeless Colombian characteristic.

Encanto avoids the compression and scrambling of chronologies (and of course the sensationalist depictions of drug violence) of Narcos or even The Two Escobars. Nonetheless, at the same time, Encanto tends to reinforce a problematic portrayal of violence as a timeless Colombian characteristic.

Related to this is the past-ness of displacement in Encanto. Most people outside of Colombia probably do not realize that over 72,000 people were displaced in 2021, a 200% increase from 2020, as the fragile gains of the 2016 peace accord are undone. Encanto’s fundamental optimism has missed its historical moment. There is another possible interpretation to be made, which I’ll return to below, but in a sense, the film’s message is more in line with the mood and conditions of Colombia circa 2017.

The Madrigals’ experience with displacement represents the inversion of what we might normally expect. Rather than fleeing the countryside for the village center or a larger town or city, Alma, her husband, and their neighbors head out of their nucleated settlement to the bush. A couple of historical parallels from the 1940s and ‘50s come to mind here. The first is an episode that I briefly describe in my book: in December 1949, a Conservative posse rode (whether on horses as in the movie, I’m not certain) into the Antioquia town of Rionegro, outside of Medellín, and torched the historic buildings facing the main plaza. In other words, violence in this period wasn’t exclusively rural, and neither was urban violence limited to Bogotá in the aftermath of Gaitán’s assassination in 1948—something we know but I think often overlook.

This brings us to a second historical parallel. Conservative police and deputized civilians assaulted populations up and down the Cauca River valley in western Colombia in the aftermath of Gaitán’s murder and the popular, largely Liberal, uprisings that followed. One of the Liberals to flee this terror was a teenager named Pedro Antonio Marín, who at that moment forever left the world of urbanized Colombia for the backcountry. Marín would later become known as Manuel Marulanda Vélez or Tirofijo (Sureshot), the legendary founder of the FARC (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) guerrilla group, which has been described as an embodiment of the armed colonization of Colombia’s internal agrarian frontiers. We could thus read the Madrigals’ story as part of this settlement of the frontier that dates back to the 19th century, and as an example of the kinds of informal authority that arise as people move out of spaces governed by formal institutions. The Madrigals’ community has a Catholic priest, yes, but no government representative that we see and no obvious connection to the outside world other than the coffee that’s being transported in several scenes. To bring in a trope about the origins of the FARC and the diffusion of power in Colombia, we have la República Independiente de Madrigal.

To change directions toward another part of the film that inverts usual narratives about Colombia, I was also struck by Encanto’s portrayal of race. The film shows us a multiracial Colombia, but one where Blackness is at the forefront and indigeneity subsumed. This is a reversal of hegemonic portrayals of modern Colombian culture and society, which tend to erase Blackness. What indigenous influences we do observe are largely limited to cultural references, such as the townsfolk wearing sombreros vueltiaos and the pre-Columbian motifs in the background of Luisa’s signature song, that have been absorbed into the mainstream of Colombian national culture and identity. Bruno’s dress and deployment of shamanistic rituals are the perfect encapsulation of this: indigenous elements appropriated and performed by a mestizo.

I’ll stick with Bruno to close on an optimistic note. The Comprehensive System for Truth, Justice, Reparation, and Non-Repetition established by the 2016 peace accord will soon conclude an important phase: the truth commission will issue its final report in mid-2022, while the transitional justice system will soon advance proposals for restorative justice. In this way, Encanto is a film for its moment. To paraphrase Colombia expert Michael Evans, the country’s institutional context may soon help enable Colombians to talk about Bruno.

Mariana Díaz-Chalela, Yale University

As someone who studies Colombian history, and who is constantly thinking about how to make Colombian history “worthwhile” for US audiences, I went to see Encanto excited and expectant of the many different ways in which the movie would portray our own version(s) of colombianidad. Among other things, the movie left me thinking about how we frame our questions when thinking and writing about our country and the many Colombias that historians have explored. It has become commonplace for those of us working in Latin America to think about the comparative and transnational bends of our projects, guided to some extent by where we can get funding and access job opportunities. We often think of ourselves as Latin Americanists, bridging our research agendas into a shared dialogue that is both incredibly fruitful—especially when compared to the prevalent national tone of some of the Colombian historiography—and also somewhat limiting. We claim the exceptionality of our national and local histories, while also making them relevant for regional and global contexts. Encanto strikes the same tone of being extremely Colombian and at the same time extremely relatable to other Latin Americans and Latinx communities. At times, I felt like the movie tried to bring US Latinx audiences in by creating an idea of Colombia that is both exceptional and somehow also regional. We don’t exactly get a sense of where in Colombia the movie is set and the ‘country of regions’ is suddenly everywhere and nowhere at once.

Another theme that I found interesting in the movie was how it portrayed rural life in Colombia. Following the idea of a ‘time-less past’ (discussed by Rob), the movie recreates a rural town that could seemingly be set in the 1950s as much as it could be set in the 1980s. Evocating a sense of terruño, the town—nameless in the movie—is the perfect picture of rural life where all neighbors are there to help you with a smile on their faces. The Madrigals are the large landowners that feel a sense of “duty” to the community, somewhat evocating large terratenientes. Yet the community is made up of a lineup of unnamed characters—apart from Mariano's family, the man set to marry into the Madrigal family. We don’t actually get to know much about the life of the town, besides the fact that the Madrigals “help out” with town activities. And yet, the movie drives the point that it is that sense of community—presumably ascribed to rural life—that rebuilds the Madrigal’s home.

Just as much as it does with geography, Encanto’s portrayal of race is everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The emphasis on representation, which seems targeted to US audiences, is welcomed and, at the same time, raises questions about the idea of diversity that the movie tries to portray. The Madrigal family members are multi-racial and multi-ethnic–even if that precise question is not openly discussed in the movie. In fact, the filmmakers have shared that one of the reasons Encanto was set in Colombia is because of Colombia’s racial and ethnic diversity, and, in particular, because the filmmakers felt Colombians embraced that diversity. In a country where racial and ethnic violence and exclusion is so prevalent, what have Colombians actually embraced about diversity? How have ideas of ‘diversity’ translated into narratives about inclusion and equality in the face of multiculturalism? What have those same narratives obscured? How can we historically think about Colombian diversity both in terms of geographies, but also of race and ethnicity? Perhaps an interesting starting point would be to rethink narratives around the 1991 Constitutional promise of multiculturalism, including who was excluded from the constitutional project, and how diversity—as a political discourse—continues to entrench such exclusions.

One of the main takes of the movie is that if contemporary ideas about memorialization seek to stress its role in reparation, it also has to deal with the fact that plural narratives open the possibility of futures that are up for grabs. We cannot have faith in memory as a tool to stabilize our expectations about the future. Repressed and unpleasant memories will emerge in transitional scenarios and a yellow butterfly that represents the unexplainable resolution to the problem, as in the film, could easily become the omen of problematic pasts and futures that need constant and pluralistic revision.

Jorge González-Jácome, Universidad de los Andes

I would like to resist the temptation of thinking of Encanto as a movie about Colombia. References to Colombian food, the cliché of changing the meaning of yellow butterflies that García Márquez originally depicted in One Hundred Years of Solitude as omens of an apocalypse, the accents, songs, and other devices seem to localize a set of problems that can occur in other places. Hence, I believe that Encanto can take place in Colombia, but also in any modern nation state that has suffered, at different points of history, the drama of violence, displacement, and reconstruction.

Thinking about Encanto in this light can help us deprovincialize part of the debate that permeates talk about the movie and ask how it can give some clues to different issues like family, gender, race, political communities, etc. In this short entry I focus on the issues related to memory raised by the movie. One of the main issues of Encanto lies in how it deals with repressed memories that surround the foundational myths about social and political communities. My take is that the film contributes to understanding of how master narratives seek to control memory and to figuring out ways to challenge these narratives. In this realm we can evaluate where Encanto lies vis-a-vis debates related to the pluralization of memories in contemporary society.

One of the main storylines of the movie focuses on the grandmother’s, Alma Madrigal, authority over the rest of her family. This power comes from a story nobody else witnessed: her past displacement from a town, the murder of Pedro Madrigal, her husband, and the birth of a “miracle” that holds together the Madrigal family and the community surrounding them. The specific contours of the “miracle” remain a mystery throughout the movie. It is physically represented by the light of a candle, the magic house, and the conferral of special—supernatural—gifts to the Madrigal family, except Mirabel, which ironically means “wondrous.”

Mirabel, however, perceives that the house, the casita, is breaking into pieces and seeks to find an explanation. In her quest to save the “miracle,” she discovers Bruno, her uncle who had a vision about the end of the “miracle” and was consequently ostracized by Alma, who thought that hiding Bruno’s vision would keep the “miracle” safe. “We don’t talk about Bruno,” one of the hit songs of the movie, depicts the anxiety that the Madrigal family feels about its exiled relative. Paradoxically, the song announces that people won’t talk about Bruno, but at the same time they do so by asserting it. Pepa, Mirabel’s aunt, tries not to mention his name in a conversation she is having with Mirabel, but her husband, Félix, enters the scene and ends up telling the story about Bruno. The repressed tries to escape from the beginning. There is an evident anxiety about repression in all of the characters. The question is thus what can Bruno, the repressed, reveal?

The short answer is that Bruno challenges Alma’s pure foundational narrative, which is stabilized by the idea of the conferral of a “miracle.” Alma wants to protect the family by conveying that the foundational moment of the family, the conferral of a “miracle,” is the end of history. Bruno defies this narrative by showing that the future is up for grabs. In the night Mirabel did not receive her gift; there was a vision of the future of the miracle: it could be its destruction or its endurance thanks to Mirabel, the giftless. “The future is undecided,” as Bruno says. The idea of Bruno as a repressed narrative is stressed by the fact that he lives within the walls of the house, in a sort of neurosis that leads him to identity problems—he uses two other names when he meets Mirabel (Antonio and Jorge)—and to a compulsive behavior of trying to amend the cracks of the casita, which evidence the gradual deterioration of the miracle.

Once Mirabel discovers that the future is up for grabs, the question is what to do with the repressed story that leads to the anxiety and neurosis of the members of the family. In one of the most interesting scenes of the movie, Mirabel and Alma, after a deep argument about the family, return to the river where the latter received the miracle. They rethink their foundation in the same place where the initial foundation of their family and community began. Alma confesses that she was afraid of losing everything and that such fear led her to repress not only Bruno but also Mirabel. The Madrigals, argues Alma, were given a second chance and she did not want to ruin it. In the same place where the first foundation was laid, Mirabel serves as a new voice that will rearticulate the beginning and the destiny of the community. Bruno arrives late to the riverside and the three of them share the moment where the repressed returns and defeats the master narrative. Madrigal is an unusual last name for a Colombian family, but in music it was a type of Renaissance composition for a plural number of voices deploying a sentimental topic. Now the new narrative is plural, and it incorporates not only the witnesses but the outcast.

The result of the new plural foundational narrative leads to a transformation of three women’s destiny. In her hurry to preserve the miracle and perpetuate the gifts of the Madrigals, Alma wanted to marry Isabella, Mirabel’s beautiful sister, to Mariano, who strongly resembles the murdered grandfather, Pedro, as if the wedding would perpetuate the foundational master narrative. Mirabel discovers that Isabella did not want to marry and that she was doing everything for the family. Likewise, Luisa, also Mirabel’s sister, has been forced to assume another important role in the family: that of a strong woman. After a new foundational narrative emerges, the wedding will not happen and Luisa can lighten the load upon her shoulders, because the idea of the family is no longer centered on reproduction, but rather on solidarity through sisterhood.

It is possible to underscore several criticisms against Encanto, but in these lines I wanted to share ideas about the memory question that emerges in the film. One of the main takes of the movie is that if contemporary ideas about memorialization seek to stress its role in reparation, it also has to deal with the fact that plural narratives open the possibility of futures that are up for grabs. We cannot have faith in memory as a tool to stabilize our expectations about the future. Repressed and unpleasant memories will emerge in transitional scenarios and a yellow butterfly that represents the unexplainable resolution to the problem, as in the film, could easily become the omen of problematic pasts and futures that need constant and pluralistic revision.