Seleucid Global? Time and Empire in the Hellenistic Near East: An Interview with Paul J. Kosmin

In 311 BCE Seleucus Nicator staged a triumphal return to Babylon. Following the death of Alexander the Great, Seleucus had been one among the emperor's many rival generals, family members, and friends fighting to gain control over the remnants of his empire. Expelled from his Babylonian satrapy in 316 BCE, Seleucus had spent the intervening years in Ptolemy's Egypt, and was returning to Babylon now to reclaim his former territories. After a brief occupancy, Seleucus had to leave the great city to subdue threats to his rule throughout the territories recently lost to his rival, Antigonus. It was not until 305 BCE that Seleucus was crowned as king of Babylonia and western Iran. He would go on to establish the extensive Seleucid Empire.

But when it came time to date the inception of imperial time, to inaugurate the "epoch," the date chosen was not 305, but 311 BCE. Why retroject the epoch to a time before the empire officially existed?

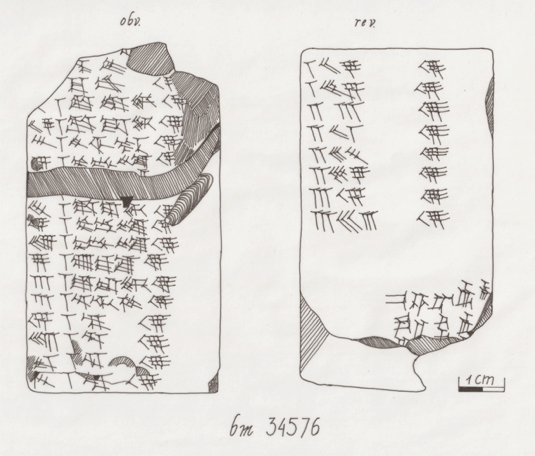

The mysterious choice to antedate the empire is resolved through a consideration of the cuneiform tablets left by Babylonian scribes, who specialized in astronomical rhythm and dynastic transition. One such text, surviving as a small fragment, describes Seleucus's return to Babylon in 311 at the beginning of the Babylonian calendrical year, but it does so, unusually for Babylonian historiography, as a coupled departure and return. The beginning of the Babylonian calendrical year was the occasion for the akītu ceremony, a festival which, in the cosmogonic and conceptual lexicon of the Enûma Eliš Babylonian creation myth, legitimized the co-rule of the god Marduk and the temporal ruler of the city. To ritualize the creation, the king would lead a procession out of the city, journeying three days to the foot of the steppe before returning. As Paul J. Kosmin points out, the "vertical profile" of Seleucus's exile in 316 and return in 311, as well as the exact date of his return to the city, coincided with both the symbology and the calendrical time of the Babylonian New Year ceremony. Furthermore, the cosmogony of the Enûma Eliš was likely grafted onto that of the Seleucid Empire, which distinguished itself as the initiator of a radically new regime of time. The inaugural date was thus what Kosmin calls a "conjunctural phenomenon," a precise grafting of the beginning of Seleucid time onto the ritual time of Babylonian cosmogony.

What's more—and what is, for these purposes, the foundational fact of Seleucid temporality—the epoch, which in the ancient world usually yoked the time of a regime to the accession of an emperor and reset with each subsequent emperor, was never reset. Instead of the ever-repeating epoch of regnal time, the Seleucids instituted a novel ongoing temporal system that mirrored astronomical practice in its autonomy. In this system, time was characteristically empty, generic, and homogeneous.

Paul J. Kosmin, a professor of history and classics at Harvard University, is an historian of the Seleucid Empire, the least remembered among the major successor states to the Macedonian kingdom of Alexander the Great. The Seleucid Empire was one of the four empires that arose in the wake of the death of Alexander in 323 BCE. It occupied an enormous landmass, taking over roughly the territory of the Achaemenids, whom Alexander had beaten out at the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BCE. From the Balkans and Coele-Syria (roughly the Levant) in the west to the Hindu Kush and the Afghan mountains in the east at its peak, Seleucus's empire encompassed a vast, uneven landscape and a remarkably diverse population. In modern scholarship, it has been vulnerable to exoticization, and viewed as the sick man of the Hellenistic world, subject to continuous territorial contraction before finally being subsumed into the Roman and Parthian Empires in the mid-late 2nd century BCE.

Kosmin's work is part of a recent historiographical move to reevaluate the familiar narrative of the Seleucid Empire as a sprawling, dysfunctional, Oriental empire. Through a study of ethnographies, surveying projects, and city foundation practices, his first book, The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire, elucidates the intricate practices by which the Seleucids founded, legitimated, and constructed the space of Seleucid rule. His most recent book, Time and Its Adversaries in the Seleucid Empire, explores the time of this empire, which he argues was radically new and can be characterized as linear, empty, and homogeneous. This new technology of time drew the empire's subjects into one commensurable temporal framework. Such commensurable time, in turn, provoked various rediscoveries of indigenous pasts within a new scheme of Seleucid time and historicality. This generated a sense of temporal incommensurability between Seleucid and indigenous times and between past, present, and future—and it played into and gave shape to an atmosphere of pan-imperial revolt.

Kosmin adduces the texture of Seleucid time—in the marketplace, in imperial archives, and in rare but suggestive Seleucid attempts to explicitly obdurate indigenous times—through the material and textual evidence of its undoing. He surveys apocalypse, historiography, symbolic violence, and evidence of ancestralizing revolts on the parts of subjects in Judea, Armenia, Babylon, and Iran. In these, he finds new modes of indigenous historiography and antiquarianism, for which Seleucid time was the condition of possibility, and apocalyptic visions of the end of the empire, conceived in the pursuit of finitude and the closure of Seleucid time through typologically foretold violence and acts of divine retribution.

- Joshua Milstein

MILSTEIN: Could you tell me a little about your books and how they relate to each other?

KOSMIN: The first book was based on my dissertation, which was concerned with the space-making practices of the Seleucid Empire. The question it answers is: "How did a conquest diaspora without connections to its homeland turn the landscape of its rule, everything from Pakistan to Bulgaria, into a Seleucid empire? How did they make the land Seleucid?" So it's very top-down. The concerns of the first book are those of centralized power and legitimacy. Yet, I felt that that the first book missed quite a lot of the story. The second book, which examines the bottom-up concerns of the empire, forms kind of a diptych with the first. In the second book the key question is: "How did the local populations slot the Seleucids into their historical frameworks?" So the two together are a project of categorical history, accounts of imperial space and indigenous time.

MILSTEIN: How did you come to study the times and histories of the Seleucid Empire and its subjects?

KOSMIN: I think the second book came about by noticing that there seemed to be an acute concern for history and durational time among the various local populations of the Seleucid empire, which wasn't present to the same degree before, and that this concern seemed to be pan-imperial. In the cases of Babylonia and Judea, which are the two big bodies of data that have survived for us, we have good evidence of this; and if you compare these cases to the preceding regimes in either Babylonia or Judea under the Achaemenids or under the Ptolemies, there is this turn towards what I would say is a concern with historicality in each place.

But the claim in the book is that ultimately this concern is a distinct, provoked response to the strange new temporal regime established by the Seleucid Empire, which rendered their past much more problematic. Claiming that the Seleucid empire essentially inaugurated a year one, from an imperial perspective, made everything before that a kind of age of ignorance, to borrow a later phrase. Further, this open futurity, which basically goes on and on forever, has taken the containment out of the world, generating a crisis of historical meaning, and in each place you see responses that are somewhat politically oriented in terms of revaluing their own local pasts.

This is basically a colonial environment in which, to put it really crudely, you have a Graeco-Macedonian governing elite who are descended from the Greek mainland or the Aegean coast of Asia Minor. This elite, coming from areas that are for the most part not within the Seleucid Empire, are ruling over local non-Greek populations and sustaining some of the indigenous structures that existed before them. So they are coopting local stakeholders and turning them into imperial agents. A good example of this is the high priest in Jerusalem, who is simultaneously a kind of agent of the empire and the highest religious official in Judea. There are obvious tensions that result from these conflicting agendas.

There is a familiar claim in post-antique history writing that one of the characteristics of modernity was "Western, empty, post-Enlightenment time" liberating itself from this enclosed providentialist time, but, as I said, still carrying on many of its dynamics. I would say one of the things my book is trying to do is reverse that order and suggest that state-directed empty time was invented first and apocalyptic eschatology or enclosed providentialist time is a dialectical response to that.

MILSTEIN: In the macro picture there are still some historians interested in both sustaining the view that Judeo-Christian time has persisted into the relative present, and, increasingly, in decoupling these adjectives. How should we understand Seleucid time vis-à-vis our received notions of Judeo-Christian time or Western time?

KOSMIN: I would say that the dominant model of Western time that we have is a contemporary empty time of one thing after another, but which contains within it fossils or traces or the dynamics of a Judeo-Christian providential time that has a clear beginning and a clear end, with a kind of unidirectional time's arrow-like movement from one to the other. There is a familiar claim in post-antique history writing that one of the characteristics of modernity was "Western, empty, post-Enlightenment time" liberating itself from this enclosed providentialist time, but, as I said, still carrying on many of its dynamics. I would say one of the things my book is trying to do is reverse that order and suggest that state-directed empty time was invented first and apocalyptic eschatology or enclosed providentialist time is a dialectical response to that.

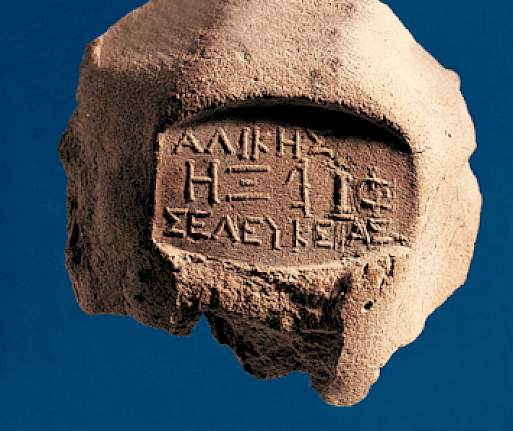

The book is making a really bold claim in saying that these two fundamental modes of thinking about durational time are invented with the Seleucids. The first is sort of an n+1 time, as in an era count of years with one thing after another without any end in sight, where time is empty, transcendent, and is just a number unanchored in realities of the world. The second is directed, divine time, which takes its meaning from the end. These two kinds of time are a twin birth of the Seleucid Empire. It's a big claim and I'm aware that the claim falls somewhere between hubris and chutzpah, but I think the evidence sustains it. I came to this claim about Seleucid time simply by looking at hundreds of thousands of ancient artefacts, which just had a number imprinted on them in some form. For instance you would have a lead weight in a market that has the number 173 on it. The number 173, in this example, is a Seleucid Era year, and that number is the authorizing device of that lead weight. It is how a kind of unitary system exists in market trade—you can trust the weights and measures going on in the market. This is one example of the use of time as an authorizing device in the Seleucid Empire. So I came to realize that for the first time in the Seleucid Empire people were inhabiting a world packed full of dates, and, crucially, dates that were relational to each other. It is an inference to claim what kind of interior sense of historicality derives from living in a world of relational dates for the first time when no one explicitly says so; but my claim is this: it has a radical effect on how people orient themselves in the world.

With the bizarre exception of the Maccabean revolt against Antiochus IV, there's no intervention in the belief systems of local populations. But through political economy, state fiscality, and day to day living in cities there is an imposition and an absorption of this Seleucid time system that has its own logics and dispensations, and it is here rather than in a kind of confessional colonialism that Seleucid time creeps in.

There's an evident danger of orientalism in an argument like this—that a sense of history and a transcendent rational enlightened time only emerges in the Near East as a result of the arrival of the Greeks. There's the danger that it ties itself into some really pernicious narratives about the Semitic world and the Greek world, which have a long backstory and which continue to have troubling consequences in the field of Classics. So I was keen to suggest that this Seleucid time was, in historical terms, a conjunctural phenomenon—that this new Seleucid time is in fact the result of Babylonian technologies. The automated calendar is especially important. For this whole system to work no intervention from the state is required. About a hundred years before the Seleucids introduced their time system, the Babylonians had figured out how to link up the cycles of the sun and the moon, a way of keeping time that can basically run by itself forever. I think it's no accident that this Seleucid time system was born in Babylon and probably—though there's no evidence of this—there was Babylonian temporal expertise behind it.

MILSTEIN: Your book uses material evidence, in particular, to get at the felt, understood temporal senses or sense of historicality among Seleucid subjects.

KOSMIN: At least in the study of antiquity the majority of writings about time deal with the most explicit, elite textual genres: they're a form of intellectual history—philosophy, theology, things like that. I was concerned to move away from that. I do of course deal with apocalyptic literature and some historiography that survives, but for the most part I am looking at the quotidian detritus that is left over from things like the archive spaces or the agora or the royal inscriptions, which were erected in the most prominent spaces in the empire. It's a very different methodology. It is not one of close reading; it's one of inference from accumulation of evidence. I think I found the most productive sites of seeing temporal encounter, temporal thinking, and temporal engagement were those where we had privileged sites of the Seleucid time regime subjected to violence, often it seems symbolic violence. In a number of places in the book I try to identify archaeological evidence of destruction as deliberate destruction directed at the Seleucid temporal regime, and in some cases to see in this evidence a kind of desire for finitude. For example, the archive in Seleucia on the Tigris, from which we have about 16,000 clay bullae, which are the clay sealings that would have bound fiscal documents from one of the capital cities of the Seleucid Empire. The only things left behind from the destruction of this archive are sealings—the year-numbers recorded on these sealings are gouged out—and it is kind of redundant in terms of violence. Another archive actually has much more gruesome evidence. The site called Tel Kedesh in northern Israel is another one of these Seleucid fiscal archives oriented to the timeline. So it's a site of kind of imperial exploitation, one that necessarily operates within the Seleucid temporal regime in terms of its dating practices and so on. This building was destroyed in the Maccabean wars, leaving behind upsetting evidence—a young child, probably very young, probably younger than one year old. The child is buried in the room and the room is sealed up and burnt and everything is destroyed, but before the baby is buried his hands feet and head are cut off. It seems to be some kind of mutilation, doing some kind of symbolic violence to the site. It's something that is very hard to interpret. There are traditions of child sacrifice in the region. There are also traditions of polluting sites so that they can never be used again. We do know that this complex is reoccupied, but that the archive room is not used again.

What I try to do in the book is match those actions that express a desire for finitude, for bringing this time system to an end, with apocalyptic literature that is being written contemporaneous to those actions in the same regions—in Babylonia, Judea, and also in Iran, but interestingly not in the Greek cities of the empire. This is apocalyptic literature that, similarly, is about undermining the royal Seleucid control over temporality and bringing the Seleucid timeline to a close. These are fantasies of the end. One of the big claims of the book is that fantasies of the end of the world are ultimately responses to the Seleucid time regime and spring up somewhat simultaneously in the core regions of the Seleucid Empire. In Iran, Babylonia, and Judea they arise simultaneously, and this simultaneity has been noted in the past. It has been explained as a kind of intellectual historical derivation of ideas: the Jews and the Babylonians are borrowing it from the Iranians, or vice versa. My claim is that actually, and ultimately, it's the common environment of the Seleucid Empire that provokes these common responses.

MILSTEIN: Could you speak briefly about the epoch? What is the distinction between regnal and dynastic dating, for instance, and total history 1 and total history 2?

KOSMIN: Maybe it's best to begin with the systems that existed before the Seleucid Empire, just to make the radical character of the Seleucid system evident. Basically there were three ways of counting time before the Seleucids. First, you could give the temporal location of an event by reference to an annual year of office—say, something happened in the year of the Roman consuls X and Y. Second, in Mesopotamia long, before the Seleucids, you would say something had happened in the year when the king did some great activity, such as reaching the source of the Tigris and Euphrates, and these would be arranged into lists. Both the consul system and these so called year dates have a narrow reach, because they are products of a kind of scribal listing system. In other words, Listenwissenschaft, which expresses a pretty widespread mode of thinking and organizing knowledge in this period. Third, and most commonly, you just count the event by the reign of the king. What the Seleucids do is they break with all this, beginning when Seleucus I returns to the complete chaos of civil war following the death of Alexander the Great and the different successor states, and afterwards as the various successor states seek legitimacy in different ways. So the Ptolemies in Alexandria, for example, tie themselves very strongly to the pharaonic royal system. The Seleucids don't do this—they hover balloon-like, to use Peter Thonemann's phrase, above the territories of the empire. In all of their imperial practices there's something transcendent about them. This also holds for their time system. So Seleucus I establishes a "year one" of his rule, retrospectively. His enthronement, actually takes place in year 6 or 7, and he later establishes year 1 on his return to Babylon in 311 BCE and it is called the epoch.

The epoch is the generic "year one" of an era system. The epoch of the A.D. system is the year of Jesus' birth. The year one of the Hijra is the year of Mohammed's Hijra. This year one, my book argues, piggybacks on the Babylonian creation myth, the Enûma Eliš, which is about the arrival of the god and the foundation of the city of Babylon. So you have the year one and there is evidence that one of the Seleucid kings, we're not sure which, founds a Temple of Day One in Babylon to commemorate ritually this big angle of time. After that no Seleucid king ever restarts the clock, so you just have this onward temporal flow. This has never happened before. It makes future thinking possible in a way that hasn't existed before. So, if you're in the 40th year of King Nebuchadnezzer III, who dies in his 43rd regnal year, how do you imagine a year 200 years in the future? It will exist, but you can't really name it, you can't number it, it doesn't have the same texture as the present. If you're in Seleucid year 100, you are confident what 100 years, 200 years, or 1000 years in the future looks like. It's got the same temporal texture. It becomes predictable. It monotonizes future time. Possibly it disenchants it. This removal of containment and opening up of regular, future numerical thinking has, I think, profound consequences.

Total histories 1 and 2 are an obvious borrowing from Chakrabarty. One of the new genres of durational time thinking that you get across the Seleucid Empire in different places, most visibly in Babylonia and Judea, are what I call total histories, which are accountings of the history of the world from the beginning—total history 1 is from the beginning up to, but stopping at, the coming of the Seleucids. An example of history 1 is an amazing text, which survives only in fragments from Babylonia, written by a priest named Berossus. He's a Babylonian priest, who writes a history of Babylonia in Greek from the beginning of the world, the creation of the world, up to the coming of Alexander the Great. Another example of my big claim in the book is that the temporal thinking of the Bible as we know it—although it's not fully canonized at this point—goes from the beginning of the world up to the end of the Persian empire, and then stops. This totalization of previous history is, I think, an effect of the periodizing distinction established by the Seleucid temporal system. Essentially, the effect of a year 1 asserted regularly through its quotidian use, and the unifying and distancing effect of inhabiting a Seleucid temporal world, is to generate a system of two periods: the now and the before. It's no accident that we begin to see the writing of history as if from a sort of point of Archimedes in time. The force of these histories lies not so much in the individual events that make them up as in their total pre-Seleucid story.

Total history 2 is I think a necessary consequence of history 1, and it encompasses what is conventionally called apocalyptic literature. In calling it total history 2, I'm not saying that these should be considered historiography, but they are ways to make sense of not just the future but also the past, and actually share the concerns of most ancient historiography, which is regime change, justice, and the succession of kings. The key difference is that they continue the story through the Seleucids and over the Seleucids to the end of history. In all these apocalypses, which are the first apocalypses, you get a sequence of empires or periods, which include the Seleucids as the last regime, and then they're followed by the reign of God, or heaven, or divinity of some kind. They bring history to a close. In doing this, I think they're basically pulling this horizon, which existed in year one, up and over the Seleucids to historicize prospectively the Seleucid regime. In doing so, they establish something like typological equivalences between the Seleucids and previous regimes, which means that the Seleucids will suffer the same fate. So, they borrow and ultimately reinscribe—though in a transcendent manner—this periodizing distinction that is common to historiography. I think that the apocalyptic literature borrows both a structure and, in a sense, function of the Seleucid regime, but jumps it forward and elevates it to heaven. To borrow from Chakrabarty, this is also a distinction between a sort of closed history, which for Chakrabarty would be the history of capital, which are all the logical antecedents of capital that lead up to capital, and the excess, the remainder, the countervailing things, the more dialogical and enchanted history. I think that what I'm calling total history 2: these complete histories of the world—seen as if from outside—total, complete, and with something like the aesthetic of the miniature. Something you can contain, look at, rotate in your hand, examine, and find the meaning of, are also sort of enchanted, dialogical.

MILSTEIN: Can we talk about some of what accompanied these indigenous revolts against Seleucid time, like ancestralizing narratives and ancestralizing violence?

KOSMIN: One of the claims is that if the Seleucids essentially cut off pre-Seleucid history, these local or indigenous populations undertook acts of self-assertion in the kind of political spaces that opened up as the Seleucids were disappearing. I would say that in many places, in Armenia, Persia, southern Babylonia, and Judea at the very least, these populations framed their self-assertions in the manner of the revivals of traditional forms, and actually of earlier state forms. So for example in Judea you would see that the Maccabees [the Hasmonean house] exert forms of violence which almost follow the scripts of the conquest of the land narratives from the Hebrew Bible, certainly the book of Joshua, but also David's violence against the Philistines. This is at least how our narratives record it, but there is also some good evidence to sustain it materially as well. Similar things take place in Iran where a dynasty, which might have initially begun as a vassal dynasty of the Seleucids but eventually tries to assert autonomy frames itself in the older anti-Greek imagery and violence of the Achaemenid Empire, the predecessor to the Hellenistic kingdoms. This also occurs in Armenia where they frame themselves in the prior imagery and monumental buildings of the Urartian kings, Urartu being an Iron Age, first millennium BCE kingdom. So there is this, I call it Altneuland, borrowing from Herzl's programmatic title (an old new land)—it is a kind of reentry into history by these local populations, which is paradoxically done by a revival of the past in a self-ancestralizing way. However, I don't think that that's a ceding of the modern to the Seleucids. Rather, I think it's a kind of reopening of the past to the present and the future.

MILSTEIN: So you can conduct a kind of Horizontverschmelzung [fusion of horizons] of Seleucid time and the time of modernity on the basis that the origins of our concepts, our temporal concepts, somehow lie in the Seleucid past?

KOSMIN: Right. I've rushed with open arms into this anachronism, because I think precisely this—that there is a conceit of modernity that modernity is doing things for the first time. But, there are many ways in which this Seleucid temporal regime anticipates or echoes later phenomena. An example would be something like Hellenization. Especially in the world of Hellenistic kingdoms after Alexander you have a bunch of local populations, particularly local elites, adopting the cultural forms of the Greek city states as well as of the Greco-Macedonian royal courts. They all begin to speak Greek, to exercise in the gymnasia, even to die and be buried in the Greek style, and historians in my field have long resisted using the language of modernization with regard to this. But, I actually think it is enabled, assisted, and conceptually ordered to the contemporary actors in the Seleucid world as something like modernization. My argument, as we've seen, is that the Seleucid world generates this sense of the now and the before—it temporalizes indigenous practices as traditional, or pre-Seleucid, or old; it introduces practices as new, therefore creating a sense of what belongs in a Seleucid temporal world and what doesn't.

MILSTEIN: So in a sense modernity is more of a procedure which anachronizes, among other things, and isn't particular to the here and now?

KOSMIN: Exactly. I'm not sure where else you would find it other than the 19th and 20th centuries, as I haven't done that work. I presume it would be as plausible at other points, and that it does exist in other places.

Something I have often wondered is: what are the aftereffects of the Seleucid system, because once it gets introduced it succeeds in demonstrating the conceptual ease and usefulness of this kind of time system to statecraft, and so it gets replicated. This kind of unified time system covers the entire empire like an umbrella and everyone can slot themselves into it, compare their own histories in some sense for the first time in an easy way, imagine a unified future. As the political unity breaks up so does the intra-imperial temporal unity, and you get copycat era systems, like the Yona Era, which, fundamentally undoes the distinctness of Seleucid time.

A whole Hellenistic Far East story of era systems actually obtains, and for which, in general terms, we have a lot of evidence, including this amazing site called Aï Khanoum. For this region, we have evidence that is conducive to telling top-down stories of territorialization—things like colonial foundations, ethnographic writings, and royal inscriptions—but it's much harder to access the sort of indigenous historicality of this region, as the evidence just does not survive. You can tell that in the successor Seleucid dynasties of the Hellenistic Far East—the Parthians, the Kushans, the Indo-Greek kings—this era counting system does get adopted and it seems to have a long afterlife in South Asia as well; for instance, in the case of the Yona Era, meaning the Ionian or Greek era, which I mentioned previously.

MILSTEIN: Looking at your book as an example of comparativism (vis-à-vis something to which all these various people are tethered) and then looking at it synchronically but across a wide geographical space, in a huge empire that holds within it some peoples who often aren't studied together, there is something remarkable in the fact that people in such disparate places, as disparate as Aï Khanoum, Armenia, and Judea are from each other, could have so much in common and react in common ways.

KOSMIN: I would say two things. The first is that the Hellenistic world is the making of a kind of Eurasian system. One could almost call it the axial age of empire. At this time we have the generation of big territorial empires, and a commonality of imperial technologies, like epigraphic writing by the king in India with the Mauryans, in the formation of the first unified Chinese empire, in the Hellenistic kingdoms, and eventually with the rise of Rome. I think that's a new phenomenon and I think it's really a phenomenon of connectivity and borrowing to a certain extent.

Then, second, for the Hellenistic east, for the Hellenistic Seleucid and Ptolemaic worlds I work on, comparative methodologies are obviously not new, but I would say that they've been used to study Hellenistic resistance solely as an historian's heuristic, where the historian is the evaluator of similitude and difference—asking for instance how distinctive or unique the Maccabean revolt is. In answer to that, scholars have worked like pearl fishers, diving down, and picking up evidence from different places. There might be comparable temple seizures in Asia Minor, or there might be similar things going on in the Greek mainland, but that's a different level of comparison by historians.

I think there are also two other kinds of comparison going on in this book. The first is within the interregional globality of the Hellenistic east, which is a phenomenon of historical process; it's something that the empires are bringing about and encouraging. Yet, I also think that the comparative gaze inheres in the ancient actors, in indigenous populations. They are thinking comparatively, maybe like in 1848 or the Arab Spring. It's an atmosphere that's difficult to describe, as weakness in one part of the empire encourages revolt in other parts. So you see that both in weaponized fighting against the Seleucids, which occurs simultaneously in different places, as well as in textual revolt in Persia and Judea. You see it in things like what I call apocalyptic, total history 2. There's a whole tradition of scholarship that is about trying to trace the genetic descent of these ideas between Babylonia, Persia, and Judea, and that's because they do share a lot in common. But they share a lot of common not because someone in Persia is reading the book of Daniel, but because populations are moving in and sharing these ideas, and there are interregional convergences in the response to the Seleucid empire. This is both an effect of the structures of the Seleucid Empire and an effect of a kind of nonimperial connectivity encouraged in the Hellenistic world more generally. That's a long-winded answer to say it exists at the level of historical analysis, but also more substantively at the level of historical actors.

This region had been connected before: it was all unified under the Achaemenids. Yet, such connectivities, proto-globalizations, whatever you want to call them, accelerate under the Hellenistic kings. I think there are a few reasons: the political economy is different and there's a privileging of cities and the encouragement of trade. For the first time the Mediterranean world discovers the monsoon winds to southern India at the end of the 2nd century BCE, and this suddenly opens up a fairly continuous trade—with all the cultural and political consequences that follow—connecting a newly unified world from the Pillars of Hercules to the straits of Malacca. This really is a new kind of globality.