Thicker Than Water: Revisiting Global Connections on the Banks of the Suez Canal with Valeska Huber

Thanks to the haze of time, the first great age of globalization during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century can sometimes seem like a golden age. It's true that we live in an age of unprecedentedly inexpensive air travel, cell phones and Skype often replacing long travel to business meetings, and financial management tools making it easier to speculate on the ups and downs of the S&P or Nikkei, the ruble or the euro. But perhaps as we find ourselves bogged down by the kinks in this new post-1970s world of re-globalization–the passport checks, the baggage fees, the broken connections–it's all the easier to reimagine the world of high imperialism, a lost golden age. Chroniclers like Stefan Zweig and John Maynard Keynes chronicled the time as an age in which

The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep; he could at the same moment and by the same means adventure his wealth in the natural resources and new enterprises of any quarter of the world, and share, without exertion or even trouble, in their prospective fruits and advantages; or he could decide to couple the security of his fortunes with the good faith of the townspeople of any substantial municipality in any continent that fancy or information might recommend. He could secure forthwith, if he wished it, cheap and comfortable means of transit to any country or climate without passport or other formality, could despatch his servant to the neighboring office of a bank for such supply of the precious metals as might seem convenient, and could then proceed abroad to foreign quarters, without knowledge of their religion, language, or customs, bearing coined wealth upon his person, and would consider himself greatly aggrieved and much surprised at the least interference.

There was perhaps no more potent symbol of this world of ultra-connectivity than the Suez Canal, built in what was still Ottoman Egypt in 1869 and connecting the Red Sea with the Mediterranean. The Canal increased world trade. It also soon became a vital strategic artery for the British Empire, since it made the "passage to India" via intermediary stations like Suez and Aden far shorter than the former trip around the Cape of Good Hope. So powerful was the imaginary of the Canal as one of the crucial changes of the epoch that, when Henry Morton Stanley finally located David Livingstone (of "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?") on the shores of Lake Tanganyika in 1871, the Canal was the first thing that came to Stanley's mind when Livingstone asked him what had changed in the world during his many years out of contact with the Western world.

Yet as Dr. Valeska Huber, a research fellow at the German Historical Institute in London, shows in her recent book Channelling Mobilities: Migration and Globalization in the Suez Canal Region and Beyond (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, paperback 2015), the Suez Canal did not so much open as channel migration and globalization during this world of increasing trade and economic integration.

Sure, the opening of the Canal made it easier for passengers—that is, especially if they were white, wealthy, British, or best, all three—to travel around the world, often unencumbered by passport checks. But our popular memory of the Canal often forgets the fact that building a giant channel of water in the middle of the Egyptian desert obstructed the migratory routes of Bedouin tribes who formerly moved from east to west. More fundamentally, the very opening of the Canal and the transformation of the region into a giant transportation hub gave rise to new worries about the movement of slaves, prostitutes, Muslim "fanatics," or disease across the region. Contemporary fears that cholera originated in India led to the imposition of quarantine and disease control regimes along the shores of the Red Sea. At the same time, shipping titans and imperial bureaucrats debated the wisdom of dividing shipping routes' staffing between Asians (for the hot and sticky days of shipping through the Indian Ocean, supposedly unbearable for the "white race") and Europeans (so as to avoid the problem of Asian or Arab crews outstaying their welcome in Southampton or the London docklands). The Canal channeled as much as it connected.

Huber's work is, then, valuable not only as an intervention into the field of Middle Eastern Studies, relying as it does on British, French, and Egyptian archives. It constitutes a welcome foray into the broader conversation about the history of globalization and the history of the late nineteenth century as a time not only of increasing connectivity, but also of increasing channelling—that is, processes and institutions whereby migration of goods and people is cordoned off, classified, or restricted, often relying on distinctions of race, sex, or level of civilization. In order to discuss Channelling Mobilities more with Dr. Huber, Toynbee Prize Foundation Executive Director Dr. Timothy Nunan (TN) made use of the twenty-first century's aforementioned telephonic tools to speak with Dr. Huber (VH) across oceans–fitting, given that telegraphic cables were just one of many pieces of infrastructure to cross the Suez Canal during the period her book studies.

•

TN: Dr. Huber, thank you for joining us today. To start off with, could you talk a bit about where you were born and raised? Was there anything in your family background leading you to history?

VH: I was raised in Berlin, which is an interesting place to be in itself. I'd like to say two things - while in Berlin, I was less interested in formal history, and it was never one of my favorite subjects at school. However, I was very intrigued and I enjoyed talking about history with my grandparents and learning about the twentieth century through people I met. Secondly, however, I really developed a passion for travel in my youth. I spent a year in France when I was 16, and I went off from there through other locations. So it was mostly through a passion for travel and languages that I came to global history.

TN: And did that passion lead you to the United Kingdom for your undergraduate education?

VH: Yes, that was part of it. I studied politics and history at the London School of Economics, and at first it wasn't clear if I wanted to work for international organizations, or continue to study history. And obviously, studying history at the LSE and living in London in the early 2000s meant an immersion into a very cosmopolitan place, one quite different from Berlin.

TN: Of course.

VH: So this experience of living in a city during my studies which was very global, and at a very global university, was quite foundational for the track I chose.

TN: And at LSE, was there an interest on your part in British history or imperial history?

VH: Absolutely. It was during my undergraduate studies that I got drawn into British imperial history, obviously Indian history, and living in this post-colonial city was a major factor, too. I worked both with faculty at LSE, but I also tried to branch out to other faculty at other institutions in London at that time. I had some problems with the very traditional definition of the LSE Department of International History, but still, it was a formative time for me.

TN: Were there any teachers that had a big influence on you?

VH: Joya Chatterjee was teaching me Indian history, and she comes out of a more traditional Cambridge School of imperial history. So in terms of grounding myself in that specific kind of historiography, that was very foundational. There was less of an emphasis on global history as we would see it now, but certainly Chatterjee was of great influence in providing me with the grounding in the sources and literature for Indian history. I then moved on to Cambridge, not to work with Chris Bayly, which would have perhaps been the obvious move, but to work on European history, in particular with Richard Evans.

Evans is, of course, a historian of Germany, but I worked with him less out of an interest in German history and more because I had developed an interest in the history of disease and more particularly the international history of disease. So, my first foray into global history, if you like, was to pursue a history of international responses to cholera epidemics in the nineteenth century, looking at them as crises that provoked global responses. People like Joya Chatterjee, who are very much Indian historians, that is, historians of India, were very formative in terms of developing my interests in this area. However, I wasn't so much interested in following their path and in choosing one area or region of study. I wanted to explore new ways to write history.

TN: It seems like an interesting generational shift – one can think of Evans' book on cholera in Hamburg, and I think that it stands as a classic on its own terms. However, now, thirty years later, one can, I think, imagine a much more self-consciously global history approach to the history of cholera in Hamburg, simply because of the way methodologies have changed.

VH: Exactly.

TN: But you of course pursued your Promotion (doctoral degree) at the University of Konstanz in Germany. Could you talk a bit about your return, if that is the right word, to Germany, and the ways in which Konstanz shaped your intellectual interests?

VH: Returning to Germany was a very conscious decision, especially to work with Jürgen Osterhammel. It was an exciting time, since as in the US and the UK, global history was just emerging as an established field in that period. Some of the most influential books, among them Chris Bayly's, were just coming out around that time. Now, in German academia, things were a bit different, at least from the point of view of the organization of Departments. Most faculties were still primarily focused on German history, so you still really were an outsider if you were working on the history of the Middle East, as I was. By then, I should add, I had settled on a region and a time, namely Egypt around 1900, but this place, this subject, was very firmly in the hands of scholars of the Middle East and Islamic Studies departments. So I felt that finding a place for myself in history faculties was hard at times.

However, Jürgen Osterhammel was a pioneer in doing that in Germany, so I always found it particularly inspiring to work with him. He always had many students working on many different regions, and he always advised us to have another adviser co-advising the doctoral dissertation with him – ideally, someone who was a regional expert, in addition to him as a general mind. I felt there was a lot of room for exploration and thinking, but here was also a feeling that this wasn't established yet, whether within the respectable confines of British imperial history or within the United States, where global history had a longer standing already its own presence, but with a different record than in Germany.

TN: More broadly, for people who are reading this as beginning graduate students or post-docs, whether it was studying Egypt or working with Osterhammel, are there any generalizable lessons you would draw from that period of your career?

VH: I'm not sure. The experience in Konstanz worked well for me, but in German graduate work, you're much less institutionally grounded than in the United States or Great Britain. Now, for me, this worked out, since I wasn't in Konstanz very much if at all. I spent a lot of time doing field work in Egypt, France, and the UK, and I spent a year in Harvard, as well.

Now, do I think this is for everyone? No. Sometimes I wished that I had a bigger cluster of similarly minded people in one place, but as long as you can create these networks yourself, I think you'll be fine. Of course, there are things like intensive language training, which are better in the American graduate system. But then again, I just went to London, to the School of Oriental and African Studies, and to the United States to do that. So it was a bit piecemeal, but I could simply put it all together. Now, I would add that today with institutions like the Global History program in Berlin, which is quite structured, it's really a different ballgame. However, in Konstanz, at the time, I sometimes felt that I couldn't get all of the training I wanted while at a small German university by just staying there. It had to be very outward looking.

TN: Well, I can sympathize with that, having done something of the reverse of you – coming out of the United States, but spending a lot of time in Germany. You accumulate a lot of frequent flyer miles, but for the kind of projects that we are pursuing, that's just necessary.

I'd like to move to the dissertation itself. You've talked a bit about having this interest in Egypt, and learning Arabic. Could you talk a bit about your initial imagination of the Suez Canal, and how that changed? Also, could you discuss the kind of sources you came across during your research? I think that one of the impressive things about Channelling Mobilities is precisely the way that you layer together these different imperial and Egyptian sources with one another, but talk a bit about how you did that.

VH: So, I think there are two questions here – firstly, how I came to study that short stretch of water between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, and then secondly, how I came to the answers I reached.

As I said, the mid-2000s were a very exciting time when it came to global history. However, I also felt that there was a lot of theorizing and not enough empirical work, so I decided that I wanted to do this spatially, finding one of these global hubs where a lot of traffic passes through. I would then study how that traffic moved through it, but also how a global system of regulation emerged around this very tightly defined space, and how mobilities were differentiated, some accelerated and others in fact slowed down or controlled more tightly, around the period around 1900, that we view as a high point of globalization. So, it wasn't really the Suez Canal per se that interested me, or even the history of Egypt, but more a spatially bounded place that would allow me to pursue these bigger themes. So I would call it finding an empirical case study to write a global history – that's what led me to Suez. I do think that this kind of work could be done for other locations; it's just that the Suez Canal was particularly exciting in that it brought together a lot of strands that I was interested in.

If the first dissatisfaction was this distinction between theorizing about global history versus actually doing it, then the second was this tendency to write quite uncritically about flows, connections—

TN: "Mobility means liberation, self-actualization, and … uh, progress!" That kind of sloganeering, no?

VH: Exactly. So, I decided to find a space that symbolized this space of connection, but also regimes of regulation and control, as well. So that was my second starting point for studying the Suez Canal.

And then the third aspect I was looking for was that I didn't want to write a migration history of only one diaspora or one group, as many books on migration history do. They start from a group of people rather than a space, but I wanted to make sure that I could keep in focus precisely how this multiplicity of different group was being channeled in different ways through a single space. And in order to do that, obviously, you had to write about multiple groups intersecting in a specific location. So I think this was the third starting point.

TN: Right, so not just the Indian hajj, for example.

VH: Precisely. Now, the second question you asked was about the sources themselves, and how I dealt with them. As you said, I had to be quite imaginative and use a lot of different sources. Some were Egyptian sources, but most of the people I write about in the book are not Egyptians, but rather Europeans who are travelling through the canal and use this space for a short period of time. And for this period, when you're talking about which imperial powers used the canal, you're really talking about Britain and France. So, I did a little bit of research in other archives, but most of the heavy archival research behind this book is done in the UK and France.

In terms of the types of archival material, I wanted to find out about different kinds of travellers through the canal – from tourists, to imperial officials, to soldiers, to illicit travelers, stowaways, pilgrims to Mecca … and so, it makes sense that you can't use the same sources to find out about these different people on the move. Consular courts, for example, turned out to be particularly useful as a body of sources. With the agreements in place in Egypt, everyone who was a foreign national in Egypt had to be judged in these consular courts rather than Egyptian courts, so you find many accounts of stowaways, seamen, and pilgrims who had gotten into trouble or simply did not possess the right papers and ended up in these courts.

TN: To reflect back on your earlier experiences, how do you think a book like Channelling Mobilities would have looked if it had been written by someone coming out of this British imperial history tradition that you talked about earlier? In other words, what is a global history perspective bringing to the table here?

VH: One big part of the book is about the Canal as an imperial relay station, and I'm very interested in the mechanics of imperialism, which is obviously formed by the movement of people to and from India or other imperial spaces. But I think that what a traditional Cambridge School approach would have done is to look much more at the diplomatic or political side of things – the work of supplying troops, making communications swifter, and so on. I was instead interested in writing a deep social history of mobility, which perhaps connects with other debates within Indian historiography, like subaltern studies, where you think it's just as important to find out about the stowaway as about the captain of a ship.

TN: Right, this all makes me think of recent work on the hajj as an inter- and intra-imperial phenomenon. One thinks here of the work of Eileen Kane on the Russian hajj, and there's a recent book on the British imperial hajj by John Slight, as well. And we've interviewed Dr. Philippa Hetherington of UCL on the so-called "traffic in women" within the Russian Empire and the early Soviet Union – so-called 'white slavery' which is also one form of mobility coming up in your book. One thing I think is helpful about Channelling Mobilities then, is that it gives us five or six different periscopes through which to examine how these trans-imperial actors – the stowaways, the slaves, et cetera – are interacting with the imperial actors who were perhaps the more traditional characters of imperial history.

VH: It is also worth mentioning the historiography of infrastructure, which is central to the book. Since I finished the book, a lot of people became interested in railroads and infrastructure, which hadn't been much on the radar of historians, beyond very standard narratives and descriptions. People began using the history of infrastructure as a kind of narrative device unto itself.

TN: To talk about the organization of the book, then, this book is divided into three big sections. You might put it into your own words, but I read this as being about imperial movements, trans-imperial movements or illicit movements, and then, thirdly, this sphere of global movement, whether disease control or the tracking of identities through space. Now, perhaps you wouldn't agree entirely with that characterization, but perhaps you could talk a bit about the organization of the problem.

VH: Of course. I wouldn't disagree with the way that you read the book, but I would stress that there were two structuring principles that shaped the book as I was writing the manuscript. One was space and the use of the canal as a connection, but also as a frontier or boundary. I play with different metaphors here. The second structuring principle are the different groups that move, ranging from tourists to troops to workers, and then Bedouin in caravans, and slavetrading and dhow ships and pilgrims. The final section narrows this down a bit more, looking at microbes and identity papers as objects that move around. So, the two big structuring themes here are space and actors on the move.

At the beginning, it was not clear which one of these structuring principles would be more important, and in the end I actually settled on combining them. As you say, there are three forms of spatial metaphor that I explore in the book – the idea of an imperial space and the Canal as a connection between parts of an Empire, and where empires observe one another, for instance when it comes to troop movements into different imperial possessions. The Canal becomes a barometer of imperial relations as well as an imperial checkpoint. I became interested, too, in how this imperial infrastructure worked from the point of view of the people who actually manned it, such as seamen, Canal workers or coal heavers.

The second is what I call the frontier of the civilizing mission. Many view the period around 1900 as marked by accelleration and mobility. But if you look at the Suez Canal, it's fascinating to see how the difference between different kinds of mobility are enforced and produced. I analyse the distinction made by imperial and élite actors, between "modern" and "traditional", "positive" and "dangerous" forms of mobility.

TN: I enjoyed the part about camel patrols.

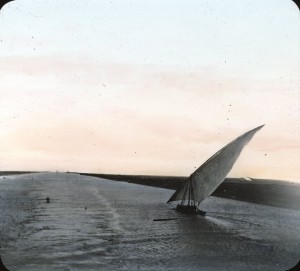

VH: That's a good example. What I find particularly interesting when looking at the deep and detailed history of the Canal is that beyond the differentiation of mobility by imperial actors, imperial regimes actually need to use these traditional forms of mobility. You can only control the Canal if you use camels; you can only control the Red Sea and slavetrading if you use traditional sailingboats. As the cover to the book insinuates, this is a space of both "modern" or imperial mobilities as well as "Oriental" mobilities. But when you examine the control regimes in detail, you see that the contrast really breaks down. The regimes that were imposed at times of cholera outbreaks, for example, often heavily relied on forms of mobility decried as "backwards" or "traditional."

TN: Indeed, these forms of mobility like steamships are not separate from, but rather very entwined with, forms of animal mobility like camels, or perhaps elephants in parts of South Asia. I think that this helps us get a differentiated view against the ideology of "mobility is always progressive," what with its emphasis on technical progress. But it also occurs to me that there are many parallels to today. In North America, for example, you have systems of biometric passports, but the TSA also employs security dogs literally sniffing you in line. Perhaps they're actually more effective in finding suspicious travelers than the layers of data and the body scanners?

More broadly, there seems to be a story in Channelling Mobilities of these regimes making investments into security, but then "deviant" actors making similar, often greater, investments to get around them. I'm reminded of recent commentary on the European refugee crisis – however many billions of Euros that have been invested in Frontex, it's obvious that refugees from Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere have also plowed billions of Euros' worth of wealth into these smuggler networks that are, to a point, effective at getting inside of the Schengen Area. Without drawing the parallel too far, it seems that we can think of this in terms of a capital and infrastructure race to penetrate or wall off territorial spaces in the name of migration control.

VH: Yes, I agree very much with these kinds of parallels you draw. This is something that I touch on more in the third part of the book when I write about identity papers when it comes to illicit travelers but also to questions who had to pay for the subsistence and relocation of travelers ending up with without funds. In the Canal Zone, you see a flourishing market in identity papers for people going on the Hajj, even though it's banned in a particular year. Mobility becomes a concern to imperial powers, but it's difficulty to control, all the more so when there are new documents allowing new forms of illicit mobility to emerge.

TN: These connections with present-day concerns over mobility lead us to the lessions that this book has for broader audiences … It seems to me that this is a book that covers the late 19th and early 20th century, but one question would be what difference the First World War makes. It seems to me that as historians of some global realm, we have a responsibility to respond to the charge of, "Well, yes, this is all very interesting, but how does it intersect with a more conservative political or diplomatic history?" What is your response to this?

VH: Initially, I was thinking of writing the book up to 1929 or the 1930s. To be honest, 1914 is not an obvious cut-off point for many of the forms of mobility I investigate. I show in the Conclusion that many of these histories of internationalization just go on in the 1920s, especially international conferences on trafficking,slave-trading or the transmission of contagious diseases. The War is interruptive, of course, but many strands simply resume in the interwar period. 1914 is not a real break in this period, and I think it's important that we challenge the direction in which we think about this.

TN: How so?

VH: People think that the period before the First World War represents a period of free movement that's interrupted by the controls introduced during the War, and that sets the stage for the 1920s. But what I show is that these control regimes actually originate in a time of high imperialism, which is seen by many as a moment of openness. Looking at an infrastructure such as the Suez Canal, the War represents much less of a rupture. Now, obviously, the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire had enormous consequences for the Middle East. But if you think about the Canal in terms of infrastructure, the real turning point is not the War, but rather the onset of air travel. If you go to a place like Suez now, it's all about container ships – it's about the movement of goods, not people, because people are travelling less and less on ships throughout the twentieth century. That, not the War, is the big shift.

TN: This reminds me of the work of the Italian scholar Giuliano Garavini, the cover of whose books bears a superficial resemblance to yours. He writes on the transformation of Europe's relationship with oil markets and global trade, but his cover is this photograph of a rather sterile container ship headed for Europe. And in contrast to your book's cover, there are no people on that cover. Now, this isn't intended as a criticism of the book – but it's just interesting how we move quite rapidly from this world of lots of people and, well, lots of camels, to something rather different after 1973, indeed before then. The way in which the history is "peopled" is different from yours.

VH: Exactly. The Canal becomes an artery for the traffic of goods, oil, and actually data, later. As I point out in the book, one of the most important data cables linking Asia with Europe and beyond goes through the Suez Canal.

TN: Another aspect of the book I think that readers will profit from is how it forces us to rethink out memory of intellectuals and authors from the period in question. I was surprised, as a non-specialist, to see one essay by Rudyard Kipling, who of course popularized the term "East of Suez," cited in the book quite a bit. It makes me think of Kipling as an author not only of South Asia, but also a writer of the Canal Region per se. More broadly, too, you offer a powerful rejoinder to the famous John Maynard Keynes quotation about no one having passports before the First World War.

VH: And Stefan Zweig, too. The problem is that, as élites, people like Keynes and Zweig were prone to think this way in terms of a borderless world, because for them, it was. I'm not claiming that before the First World War, first-class travelers had to pass through some burdensome paper check. But I think the history becomes more interesting when you try to write a deeper social history of mobility, and the worries associated with mobility become more clear.

TN: The other broad impact of this book that I'd like you to discuss is whether Suez is unique. To what extent can your reflections about "channelled mobilities" be extended to other case studies?

VH: In other words, is this a specific case, or is it a general story about global mobility? I'd like to think that it's both. I engage with general histories of the Middle East, Looking at a global space within the Middle East can help open up debates in Middle Eastern history to discussions happening in other fields. In that sense, I would argue for uniqueness, but for Suez as a Middle Eastern space, but one still connected with global phenomena.

Beyond being grounded in Middle Eastern history, is this a general story or not? I'm very much in favor of looking at case studies in detail and finding specific travelers, so I wouldn't want this to be a generic history of globalization. At the same time, this is a book that's informed by critical histories of globalization. Airports are a good analogy here, where there are similar procedures of sorting travelers. In this sense, I think that Suez offers a specific case to speak to more general theoretical debates that are perhaps taking place in disciplines like sociology.

TN: Sure. It occurs to me that today a first-class ticket buys you not just a bigger seat, or a lie-flat bed, but also a completely different security experience, sometimes from the moment you leave your hotel room.

VH: Of course. And one of the vignettes that emerges from the archives is how infuriated nineteenth-century first-class travelers are when they are subject to sanitary control or when they don't have access to lounges – these spaces where you can be separated from life in the harbor and enjoy your telegrams. I would hope that Channelling Mobilities speaks to the theoretical discussions on this. Indeed, I hope that it speaks to audiences interested in the social history of disease and the history of labor, helping us think about how to conceive realms of the global. Often, global histories that focus on telegraphs, for instance, are great, but they miss the social history dimension, and that's something I hope to bring to the table.

TN: Yes, well, in any event it's a major improvement from the state of the literature, say, ten years ago, when we were dealing with critiques about the field merely being a history of globalization. Now, thanks to works like Channelling Mobilities, not only is there the empirical dimension, but you also have really critical accounts of how restrictive globalization was for the stowaways, for those ill with cholera.

To begin to draw to a close, could you talk about your current research project? Was there any connection between Channelling Mobilities and it?

VH: I have moved on from the infrastructure of transportation to the infrastructure of communication. In my second project, I'm interested in the history of communication and information, so if you like, there's a connection, where I'm still interested in the social aspects of globalization, but now the core question is, "Who's reached by information?" This sounds incredibly broad, but if the question in the first book is "Who is actually mobile and what does it mean?", now the big question is "Who is actually reached by information campaigns?" On the level of ideas, how does communication with broader sections of the population become central in the twentieth century , but this is also a story of practice.

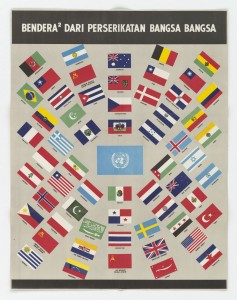

My project, which begins in 2017, has two parts. It's called "Reaching the People" and is about communication and global order in the late colonial moment and the early years of decolonization. It's being funded by the Emmy-Noether Program of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. I'm very much looking forward to it!

TN: And this will be hosted by the Freie Universität Berlin, correct?

VH: That' s right. So there's exciting things happening institutionally, but perhaps I should comment on my specific project within this realm of issues. My specific project is called "Information for All," and it looks at how experts were thinking about global communication and reaching the masses, to use the language of the 1920s and 1930s. I'm interested in this question of how information was to be delivered to the masses, especially in the context of the late British Empire.

I'm looking at four fields, which are all connected to specific actors that I'm following. One is language, looking at experiments with global languages, obviously using English as a central case study. The second is literacy campaigns, this question of whether you could reach the masses through widespread literacy campaigns. One thing of interest here is that American and British actors look at the USSR in the interwar period and are using this as an example of how they can acheive their aims. A third section is libraries, as a kind of nexus from which printed material can be disseminated; and the fourth theme is radio, film as "new" technologies of communication.

TN: Well, I can certainly see connections where this would interest different audiences. One of the recent interviews we've done was with the historian Elizabeth Borgwardt, who writes on FDR and the United Nations and so on. But my impression of that literature is that it's still something of a mystery how the American population, which is notoriously isolationist in the years before the Second World War, is turned around and convinced so quickly to support world government, in some sense, under the United Nations. And – again, speaking as an outsider – it seems like this is one of the areas in that literature where your project makes a really important intervention.

TN: Well, I can certainly see connections where this would interest different audiences. One of the recent interviews we've done was with the historian Elizabeth Borgwardt, who writes on FDR and the United Nations and so on. But my impression of that literature is that it's still something of a mystery how the American population, which is notoriously isolationist in the years before the Second World War, is turned around and convinced so quickly to support world government, in some sense, under the United Nations. And – again, speaking as an outsider – it seems like this is one of the areas in that literature where your project makes a really important intervention.

VH: Yes, exactly, in fact, I've looked through some of those materials! One of the questions that guided me from the beginning of thinking about this project was where the people were in this history of internationalism, global order or "world government". We have histories of the League of Nations and internationalism more broadly in the 1920s, for instance by [former Global History Forum interviewee] Susan Pedersen, Mark Mazower or [TPF Trustee] Glenda Sluga. But at the same time, we have an interesting literature on population growth and the masses, and so on. I've just been reading Alison Bashford's book on population control, for instance, which covers much of the same period as these histories of internationalism. However, I have found that these two historiographical discussions don't speak to one another very well. That's something that my my project on mass communication could do.

TN: Very much so. I would agree that in spite of much growth in the interwar internationalism literature, there are some blind spots. And whether it's bringing in these big themes like population control, or bringing in new actors, like, say, Germany as a champion against the League's mandate system or the Soviet Union as an alternative vendor of visions of interationalism, there's a lot to be done.

I'd like to end by asking you a traditional last question for the Global History Forum – what are you reading? What books are on your bookshelf, or your nightstand? They need not directly relate to your main research agenda.

VH: I recently organized a conference on the global public at the German Historical Institute, which very much connected with the themes we just discussed. Among the papers discussed there are definitely a few emerging books that that I'm looking forward to a lot. You may know the work of Heidi Tworek, for example, but I'm also interested in scholars trying to de-center this history. Jim Brennan, for example, is writing a history of news in Africa. But – and here, we come back almost to some of the main content of our conversation – there are questions about how much we can actually say about who is actually reached by these news organizations. Scholars on mass campaigns, for instance in China (such as Jennifer Altehenger) might have answers on this question.

TN: Terrific! Thank you, Dr. Huber.

VH: Thank you.

•

"If you truly wish to find someone you have known and who travels, there are two points on the globe you have but to sit and wait, sooner or later your man will come there: the docks of London and Port Said." If Rudyard Kipling's words are any guide, it's no wonder why Huber's global history of mobility in the Suez Canal, and our conversation about it, has touched on such a wide range of topics.

After our conversation with Dr. Huber, we've learned a great deal about the ways in which the Suez Canal not only forged new kinds of mobility, but also channeled these mobilities in ways according to their "legitimate" or "illegitimate" nature. As we've discussed in our interview, while some of these channelling phenomena might be particularly visible in the case of the Suez Canal, few were unique to it, or to its age. Hence, whether you are a scholar of Suez's cousins like the Panama Canal or the Kiel Canal, or interested in more present-day discussions about airport security or the possible construction of new mega-canals connecting the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea, or the South China Sea to the Indian Ocean, there's much to learn from Huber's account.

We know that we at the Toynbee Prize Foundation are not alone in having enjoyed Channelling Moblities, and we look forward to her forthcoming work on the history of international communication, as well. We thank Dr. Huber for the conversation, and congratulate her for discussing her work on this, the latest installment of the Global History Forum.